Readings for use in worship. The readings on this Web page are either (a) my work and marked with a Creative Commons license; (b) in the public domain (published 1925 or before) and marked “public domain,” or if arranged by me marked CC0; (c) used by permission of the copyright holder. This Web page as a whole is copyright © 2021 Dan Harper; you may use the copyright-free readings on this page, but you may not publish this page as a whole, nor may you use my commentary or my arrangement of readings into categories, nor any other copyright-protected aspect of this page.

I have to mark this Web page as copyright-protected, because a previous version of this page has been widely copied and reposted online by unscrupulous people. Please respect the moral and legal rights of copyright holders.

I've made an effort to find readings that can be safely used in online worship services without violating copyright. Many of these are readings by Unitarian and Universalist authors, who may not be well-known but can still inspire us today.

Some of the readings on this Web page don't fit into the current feelings of piety amongst Unitarian Universalists. For example, I've included the famous phrase from the Hebrew Bible, “Let justice roll down as waters....” However, I included material that gives the angry emotional context for that phrase. Unitarian Universalists may prefer to ignore this anger, but it was certainly understood by Dr. King when he famously used that phrase.

I've researched the origins of readings carefully. In one or two cases, I've included readings that correct misattributions and misquotations for readings in the 1993 hymnal Singing the Living Tradition. For example, I discovered that a responsive reading in the hymnal was not only incorrectly attributed, but was also altered by removing a reference to Allah. It's good that we reach out to find sources of inspiration in other religious and cultural traditions, but too often we warp what others say to conform with what we want them to say. Rather than editing someone else's thoughts and feelings to match our own, let's listen to what they actually have to say.

Finally, I've included some material that I've written, not because I think I'm a better writer than you are, but in the hopes of inspiring other Unitarian Universalists to create their own readings for use in worship services.

A. Opening words

B. Words for Lighting a Chalice

C. Words for the Offering

D. Readings on Truth and Beauty

E. Readings on Hope, Courage, and Love

F. Readings on the Great, the Brave, and the True

G. Liberation and Universal Love

H. The Wheel of the Year

I. Closing Words

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith —

Let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.

— Abraham Lincoln, 1860 CC0

They drew a circle that shut me out —

Heretic, a rebel, a thing to flout.

But Love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle that took them in.

— Edwin Markham (Universalist), public domain

The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measure.

It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers.

It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and flow.

I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages dancing in my blood this moment.

— Gitanjali 69, Rabindrinath Tagore (1910), public domain

Tagore, who won the Nobel prize in literature, was affiliated with the Brahmo Samaj, a Hindu group that both influenced and was influenced by American and British Unitarians.

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

The flaming chalice has become the symbol of Unitarians and Universalists around the world.

Congregations around the world recognize the flaming chalice as their symbol:

Unitarians in the Czech Republic, in Australia, and the in Khasi Hills of India;

Universalists in the Philippines; Unitarian Universalists in Brazil.

For Unitarians and Universalists all around the world

The flaming chalice symbolizes religious freedom and the quest for justice.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Here we have gathered, nurtured by the truth that some call God, and some call the highest and best in life;

Bound together by our common humanity and led by great spiritual teachers of past and present, near and far;

We light a flame to symbolize our search for salvation through our actions in this world;

Our quest for true peace and true justice, here on earth, in our own time.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The light of the ages has brought wisdom and truth to all peoples, in all times of human history.

The light of this flame reminds us to seek wisdom in our own time.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The cosmos, which is the same for all, was made by neither gods nor humanity;

But it has ever been, and ever shall be, the flame of justice and the light of truth.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist), inspired by Heraclitus fragment 30 (as translated by John Burnet) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Fire sends forth its far-spreading luster: bright, radiant, and refulgent like the Dawn.

Its splendor shines forth, and awakens our longing thoughts.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist), inspired by the Rig Veda, Book VII, Hymn X, v. 1 (as translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

These may be read by a worship leader. No. 2 could serve as a unison reading.

In eighteenth century North America, government money supported certain chosen congregations. But Universalists in Massachusetts fought a legal battle to establish the principle that tax dollars should not support one state-sanctioned church. We are inheritors of that Universalist tradition, and we receive an offering each week as a public witness of our continuing commitment to religious liberty. By contributing to this monring's offering, you can publicly affirm your support for the principles of religious liberty.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

As a part of the free church tradition, we accept no money from any governmental body, nor do we receive money from any ecclesiastical authority, in order to remain free to govern ourselves. In addition to their annual pledges, each week our members and friends may choose to give a small additional contribution as a public witness that we are, and remain, a free congregation.

— adapted from words used in the Unitarian Universalist Society of Geneva, Ill., and posted on this Web site by permission off and on since I worked there in 2004-2005

Unitarian Universalism has ancient roots in the radical left wing of the Christian tradition. Our custom of taking an offering during the worship service can be traced back to the earliest Christian communities. Those early communities helped people who were in need. Each week, those who could afford to do so brought food to offer during the worship service: bread, cheese, olives, wine, dates. After the offering had been gathered, everyone shared a plentiful meal together. Thus the gathered community made sure that everyone had at least one good meal a week. Today, in our contemporary version of that ancient tradition, all the money we collect during the offering will go to people in the wider community who are in need. [Say where the money from the offering will be given.]

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

The Way that can be walked upon is not the enduring and unchanging Way. The name that can be named is not the enduring and unchanging name.

If we conceive of it as having no name, it is the originator of heaven and earth. If we conceive of it as having a name, it is the mother of all things.

When we are found to be without desire we may sound its deep mystery. When we are consumed by desire, we shall only see its outer fringes.

Beneath these two aspects, it is really the same

But as development takes place, it receives the different names. Together we call them the Mystery.

Where the Mystery is the deepest is the gate of all that is subtle and wonderful.

— from the Dao de Jing (Tao te Ching), Book I, trans. James Legge CC0

In accumulating property for ourselves or our posterity, in founding a family or a state, or acquiring fame even, we are mortal;

But in dealing with truth we are immortal, and need fear no change or accident.

The oldest Egyptian or Hindu philosopher raised a corner of the veil from the statue of the divinity...

And still the trembling robe remains raised, and I gaze upon as fresh a glory as that first vision.

It was I in the ancient philosopher that was then so bold, and it is that ancient philosopher in me that now reviews the vision. No dust has settled on that robe; no time has elapsed since that divinity was revealed.

That time which we really improve, or which is improvable, is neither past, present, nor future.

— adapted from “Reading,” Walden, Henry David Thoreau (Unitarian) CC0

Where shall you seek beauty, and how shall you find here, unless she herself be your way and your guide?

And how shall you speak of her except she be the weaver of your speech?

The aggrieved and injured say, Beauty is kind and gentle. Like a young mother half-shy of her own glory she walks among us.

And the passionate say, Nay, beauty is a thing of might a dread. Like the tempest she shakes the earth beneath us and the sky above us.

The tired and weary say, Beauty is of soft whisperings. She speaks in our spirit. Her voice yields to our silences like a faint light that quivers in fear of the shadow.

But the restless say, We have heard her shouting among the mountains, and with her cries came the sound of hoofs, and the beating of wings and the roaring of lions.

All these things have you said of beauty, yet in truth you spoke not of her, but of needs unsatisfied, and beauty is not a need but an ecstasy.

It is not a mouth thirsting nor an empty hand stretched forth, but rather a heart enflamed and a soul enchanted.

— arranged from “The Prophet” by Kahlil Gibran, adapted by L. Griswold Williams (Unitarian) CC0

Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore gain wisdom;

and with our gain, also gain understanding.

Wisdom is more precious than rubies;

None of your jewels may be compared to her.

Length of days is in her right hand,

In her left hand are riches and honor.

Her ways are ways of pleasantness,

And all her paths are peace.

She is a tree of life to those who lay hold of her,

And happy is everyone who has wisdom.

— arranged from Proverbs 6.7, 18, 26-27; 4.13-18; trans. George Noyes (Unitarian), Translations of the Psalms and Proverbs (Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1886) CC0

It is wise to hearken, not to me, but to the Logos — the Law of all things — and acknowledge the oneness of the universe.

This Law is true forevermore, yet humanity is as unable to understand it when they hear it for the first time: all things are one.

Wisdom is but one thing: to know the thought by which all things governed.

And all human laws are fed by this one divine law. It prevails as much as it will, and suffices for all things with something to spare.

— arranged from Heraclitus, trans. John Burnett CC0

Shun passion, fold the hands of thrift,

Sit still, and Truth is near;

Suddenly it will uplift

Your eye-lids to the sphere.

Wait a little, you shall see,

The portraiture of things to be.

— poem from “Fragments on Nature and Life,” Ralph Waldo Emerson, public domain

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

— William Carlos Williams (Unitarian), no. XXII in Spring and All (1923), public domain

A lifelong Unitarian with a Puerto Rican mother, Williams is one of a very few famous Latinx Unitarian Universalists. Sadly, his poetic voice mostly does not fit in with today's notions of what constitutes Unitarian Universalist piety.

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

Begin the morning by saying to yourself: Today I shall have to face an idle person; an unthankful person; a false or envious person; an unsociable and uncharitable person.

Then say to yourself, All these ill qualities have happened to them only through ignorance of what is truly good.

But I am one who understands the nature of the Good: I understand that only the Good only is to be desired. And I am one who understands the nature of that which is bad: I understand that is what is truly shameful.

And I know that all these people, idle or unthankful or false or uncharitable, they are my kinsfolk. We are not related by blood, but we are related because we all participate in the same reason, the same particle of divinity.

How can I either be hurt by any of them, since it is not in their power to make me incur anything that is truly reproachful? How can I be angry, and ill-affected towards them, who by nature are so near to me?

For we are all born to be fellow-workers, just as as the feet, the hands, and the eyes must work together. So may we understand the nature of the Good.

— arranged from Marcus Aurelius, trans. George Long, Meditations, book I, no. XV CC0

Certain facts have always suggested the sublime creed, that the world is not the product of manifold power, but of one will, of one mind;

And that one mind is everywhere active, in each ray of the star, in each wavelet of the pool; and whatever opposes that will, is everywhere balked and baffled, because things are made so, and not otherwise.

Good is positive. Evil is merely privative, not absolute: it is like cold, which is the privation of heat. All evil is so much death or nonentity.

Goodness is absolute and real. All things proceed out of this same spirit, which is differently named love, justice, temperance — just as the ocean receives different names on the several shores which it washes.

All things proceed out of the same spirit, and all things conspire with it.

When we seek good ends, we are strong by the whole strength of nature.

— arranged from Ralph Waldo Emerson (Unitarian), “Divinity School Address” CC0

If we agree in love, there is no disagreement that can do us any injury,

And if we do not, no other agreement can do us any good.

— Hosea Ballou (Universalist), conclusion of Treatise on Atonement, 1805, public domain

Life has in it a re-creating force. This force brings to us the sweetest results; it can remove the scar and destroy every sign of injury.

Each great thought emerging in our brains gives to us a new re-creative force, and puts new life in what appeared to be mud and dust.

Through intellect and affection, new life comes to fainting souls. Every new burst of emotion arouses the will, and it is through action that character arises.

So it is that we can change our lives. Our destinies are in our hands: what we love is what we become.

The greatest power is a loving power. But how can we know that great power?

We know it only through the touch of human love.

— adapted from a sermon by Eliza Tupper Wilkes (Universalist), preached May 6, 1895, in Palo Alto, California CC0

Let us make songs for the people

Songs for the old and young;

Songs to stir like a battle-cry

Wherever they are sung.

Not for the clashing of sabres,

For carnage, nor for strife;

But songs to thrill the hearts of all

With more abundant life.

Our world, so worn and weary,

Needs music, pure and strong,

To hush the jangle and discords

Of sorrow, pain, and wrong.

Music to soothe all its sorrow,

Till war and crimes shall cease,

And human hearts grown tender

Girdle the world with peace.

— arranged from “Songs for the People,” Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (Unitarian) CC0

It is rather absurd to suppose a heaven filled with saints and sinners shut up all together within four jeweled walls and playing on harps, whether they like it or not.

I have faint hopes that after another hundred years or so, it will begin to dawn on the minds of those to whom this idea is such a weight, that nobody with any sense holds this idea or ever did hold it.

To the Universalist, heaven in its essential nature is not a locality, but a moral and spiritual status, and salvation is not securing one place and avoiding another, but salvation is finding eternal life.

Eternal life has primarily no reference to time or place, but to a quality. Eternal life is right life, here, there, everywhere.

Conduct is three-fourths of life.

This present life is the great pressing concern.

— from “Why I Am a Universalist,” Phineas Taylor Barnum (Universalist) CC0

A common origin for humanity means a common relationship. We may deny the fact, as many have denied it. We may exalt one person to kingship and reduce the other to beggary. But the fact of our common relationship persists through all denial and partiality.

This fact has been established by the physical and chemical sciences. It is the creed of all universal religion. It is the burden of sociology. The unbreakable relationship of all humanity, black or white, strong or weak, rich or poor, has become the established postulate of all clear thinking.

Universalism believes in the common destiny of humanity in all times and in all stations of life.

It believes that all human souls have a spark of this divine in their nature, and eventually, all those human souls will reach a perfect harmony.

Never was there such a bold proclamation of our common humanity;

Never such implicit faith in the solidarity of the human race.

— adapted from “The Social Implications of Universalism” (1915), Clarence Skinner (Universalist), CC0

Where Skinner had “brotherhood” or “mankind,” I substituted degenderized alternatives, on the assumption that had Skinner lived today he would have done the same.

All human loves rise and merge into one that is higher, more abiding and calm.

If we lean less on these human loves as we proceed through life, it is not from ingratitude nor self-sufficiency, only because some inward support has grown stronger.

So we prepare for the last brief journey each must make alone, upheld and made unafraid by those forces of soul and character we are now gathering.

Drawing every day a little nearer the unknown, its mystery allures us more and more, losing dread and growing in a kind of sweet invitation.

It hushes the old unrest, alleviates hurts and wrongs once hard to bear.

We cease to be mere earth-travelers; we never were.

— from “The Western Slope” (1903), Celia Parker Woolley (Unitarian), CC0

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

Simple, sincere people seldom speak much of their piety.

It shows itself in acts rather than in words, and has more influence than homilies or protestations.

— Louisa May Alcott (Unitarian), Little Women, ch. 36, public domain

We shall beat our swords into plowshares, and our spears into pruning hooks:

Nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

But we shall sit, every one, under our vine and under our fig tree;

And none shall make us afraid.

— arranged from the Hebrew Bible, Micah 4.3-4 CC0

The sage, looking up, contemplates the brilliance of the heavens, and, looking down, examines the definite arrangements of the earth; and thus knows the causes of that which is obscure, and the causes of that which is bright.

The sage will trace things to their beginning, and follow them to their end; and thus knows what can be said about death and life.

There is a similarity between the sage and the cosmos, and hence there is no contrariety between the sage, and heaven and earth.

The sage cherishes the spirit of generous benevolence, and can love without reserve.

— arranged from “The Great Treatise”, Yi Jing (I Ching), trans. James Legge CC0

Make me a grave where'er you will,

In a lowly plain, or a lofty hill;

Make it among earth's humblest graves,

But not in a land where men are slaves.

I could not rest if around my grave

I heard the steps of a trembling slave;

His shadow above my silent tomb

Would make it a place of fearful gloom.

I could not rest if I heard the tread

Of a coffle gang to the shambles led,

And the mother's shriek of wild despair

Rise like a curse on the trembling air.

I could not sleep if I saw the lash

Drinking her blood at each fearful gash,

And I saw her babes torn from her breast,

Like trembling doves from their parent nest.

I would sleep, dear friends, where bloated might

Can rob no one of their dearest right;

My rest shall be calm in any grave

Where none can call another a slave.

— arranged from “Bury Me in a Free Land,” Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (Unitarian) CC0

Conceal yourself in a thousand forms,

Still, All-beloved, at once I know you;

Fling a magic veil over yourself,

All-present, at once I know you.

In the growth of the young cypress,

All-beautiful, at once I know you;

In the canal's clear stirring waves,

All-flattering, well do I know you.

When the jet of the water unfolds and rises,

All-playful, how gladly I know you;

When the cloud above shapes and reshapes,

All-manifold, there I know you.

On the flowery carpet of the meadow,

All-colorful, how beautifully I know you;

In the vine twining with a thousand arms,

O All-embracing, there I know you.

When the morning ignites on the mountain,

There too, All-cheering, I greet you;

Then in the pure heavens arching over me,

Then, All-heart-expanding, I breathe you.

What I know, through inward or outward sense,

You, All-teaching, I know through you;

And when I say Allah's many names,

With each one sounds a name for you.

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, West-Eastern Divan, arrangement and translation Dan Harper CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

In the hymnal Singing the Living Tradition (1993), a translation of this poem titled “Beloved Presence” is incorrectly attributed to Mohammad Hafiz, and is categorized under “Wisdom from the World's Religions: Islam” (curiously, the version in the hymnal leaves off the last verse which contains the most explicit reference to Islam). Goethe had read Hafiz in translation, and was inspired by the ancient Persian poet; yet the poems in West-Eastern Divan are not translations but rather Goethe's Western European poetic engagement with Hafiz. Thus, in a post-colonial reading, this would not be considered an Islamic poem, but rather a Western European Romantic poet's engagement with or impression of an ancient Persian poet's Islamic poem. Note that in the last verse, I decided to interpret Goethe's poetic formulation “Namenhundert nenne” as “many names”; in the Qu'ran, Allah has ninety-nine names, and a literal translation of Goethe's phrase to “one hundred names” seemed unnecessarily distracting. For reference, I'm including the original poem in German below, arranged as a responsive reading.

In tausend Formen magst du dich verstecken,

Doch, Allerliebste, gleich erkenn ich dich;

Du magst mit Zauberschleiern dich bedecken,

Allgegenwärtge, gleich erkenn ich dich.

An der Zypresse reinstem jungem Streben,

Allschöngewachsne, gleich erkenn ich dich.

In des Kanales reinem Wellenleben,

Allschmeichelhafte, wohl erkenn ich dich.

Wenn steigend sich der Wasserstrahl entfaltet,

Allspielende, wie froh erkenn ich dich!

Wenn Wolke sich gestaltend umgestaltet,

Allmannigfaltge, dort erkenn ich dich.

An des geblümten Schleiers Wiesenteppich,

Allbuntbesternte, schön erkenn ich dich;

Und greift umher ein tausendarmger Eppich,

O Allumklammernde, da kenn ich dich.

Wenn am Gebirg der Morgen sich entzündet,

Gleich, Allerheiternde, begrüß ich dich,

Dann über mir der Himmel rein sich ründet,

Allherzerweiternde, dann atm ich dich.

Was ich mit äußerm Sinn, mit innerm kenne,

Du Allbelehrende, kenn ich durch dich;

Und wenn ich Allahs Namenhundert nenne,

Mit jedem klingt ein Name nach für dich.

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, West-östlicher Divan public domain

Can we follow Jesus? If by this is meant — “Can we deduce from his teachings a set of rules by which we can regulate our conduct and be sure we are right in every instance?” — we must answer, “No.”

We can neither follow Jesus nor anyone else, and to seek such a leader is to belittle ourselves and to belittle Jesus.

— E. Stanton Hodgin (Unitarian), quoted in “Three Los Angeles Ministers Make Sensational Attacks on Orthodoxy,” Los Angeles Herald, 17 May 1909, public domain

Hodgin, a Unitarian minister, was invited to sign the Humanist Manifesto in 1933. But although he felt aligned with humanism, he refused to sign something that sounded to him too much like a creed.

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

Let the horizon of our minds include all humanity:

The great family here on earth with us;

Those who have gone before and left to us their heritage of their memory and their work,

And those whose lives will be shaped by what we do, or leave undone.

— arranged from Samuel Crothers (Unitarian, 1857-1927) CC0

If instead of indulging in pious platitudes about a perfect God doing all things well, we were all resolved to do as well as we can with the things within our reach,

There would be such improvement in human conditions that we would be astonished at our own achievements.

War, the summation of all iniquities, is buttressed, defended, and excused by all of the primitive and reactionary dogmas and traditions.

If a holy zeal to accomplish what is within our collective reach seized a majority of the human race, war and all the brood of evils that go with it would not long survive.

We are, in our collective capacities, the imperfect divinity that must make the world over into the kind of abiding place that we know it ought to be.

We cannot escape our divine responsibilities, however imperfect we are.

— arranged from the 1925 sermon “Speak to the Earth” by E. Stanton Hodgin (Unitarian), CC0

The children of Adam are limbs of each other

Having been created of one essence.

When the calamity of time afflicts one limb

The other limbs cannot remain at rest.

If thou hast no sympathy for the troubles of others,

Thou art unworthy to be called by the name of a human.

— adapted from Sa'di (Muslim), the Gulistan, Story 10, Ch. 1; public domain translation CC0

Universalism believes in the universal relationship of all humanity.

A common origin means a common relationship. We may deny the fact, as many have denied it.

We may exalt one person to kingship and reduce the other to beggary. But the fact of our common relationship persists through all denial and partiality.

Universalism believes in the common destiny of humanity in all times and in all stations of life.

Universalism believes that all human souls have a spark of this divine in their nature, and eventually, all those human souls will reach a perfect harmony.

Never was there such a bold proclamation of universal human relationship; never such implicit faith in the solidarity of the human race.

— arranged from “The Social Implications of Universalism” (1915), by Clarence Skinner, a Universalist minister prominent in the Social Gospel movement of the early 20th century. CC0

I despise your feast days, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Though you offer me burnt offerings and your meat offerings, I will not accept them:

Neither will I look at the peace offerings of fatted animals you make. Take away from me the noise of your songs; for I will not hear the melody of your harps.

Let justice run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream.

— Amos 5.21-24 CC0

Let me give you a word of the philosophy of reforms. The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions, yet made to her august claims, have been born of earnest struggle.

The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing.

If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground.

They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

Find out just what a people will submit to, and you have found out the exact amount of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them; and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both.

— from “An address on West India Emancipation,” Frederick Douglass, August 4, 1857 CC0

Cautious, careful people, always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform.

Those who are really in earnest must be willing to be anything or nothing in the world’s estimation.

— “On the Campaign for Divorce Law Reform,” Susan B. Anthony, 1860 CC0

Confidence in the successful outcome of a cause energizes the will, and creates a contagion of faith.

Belief that they will recover from an illness does not enervate the patient, but gives them renewed effort.

It is reasonable to expect that faith in the final triumph of good over evil will operate likewise.

This most splendid of all hopes, radiant, joyful, pulls us into the battle line against evil, and puts into our souls that unshakable trust which makes our onrush like that of a thousand storms.

— arranged from “The Social Implications of Universalism” (1915), Clarence Skinner (Universalist) CC0

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action,

Into that heaven of freedom, my God, let my country awake.

— adapted from Gitanjali 35, Rabindrinath Tagore, 1910 CC0

Along with Gandhi and others, Tagore was one of the architects of modern India, encouraging people to think beyond Britain's colonial domination of India; today, we're beginning to understand how decolonization needs to happen even within the boundaries of a colonial power like the U.S. In this poem, Tagore originally wrote “my Father,” but because he was a progressive in his own day I feel he would understand today's efforts to use degenderized language to refer to what he called “the One Supreme Being.”

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

From the east, out of the air, the growing brightness of dawn comes each day.

May the rising sun bring me wisdom, may all beings share in the enlightenment I seek.

I await the light of gentle dawn in my dreams, clearing my thoughts for wisdom.

From the south, where summer never ends, comes the warmth that makes earth green and good.

May the work of my hands transform the world for good, as the summer sun ripens fruit and makes it sweet.

I await the fire and passion of summer entering my dreams, guiding me to create a world where all may live in peace.

From the west comes the power of the drenching storm, the surging waves, thunder and lightning, and the sweet waters of the rivers.

May the power of the waters wash away injustice and hatred from my heart.

I await the gentle mists flowing into my dreams, filling my heart with love for all beings.

From the north the groaning winter winds bring death of the old year, preparing the land for birth and new life.

I will draw strength from the darkness of winter, the darkness of the earth where seeds lie dormant, waiting to grow.

Into my dreams shall come mystery and power, and wonders of life and death.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The above reading could be used for weekly worship services, or for Unitarian Universalist observations of Neo-pagan quarters and cross-quarters. It works as both a responsive or antiphonal reading, or it could be read by persons or groups in each of the four directions.

These days when the trees have put on their autumnal tints are the gala days of the year, when the very foliage of trees is colored like a blossom. It is a proper time for a yearly festival.

Some maples when ripe are yellow or whitish yellow; others reddish yellow; others bright red; by the accident of the season or position, the more or less light and sun, being on the edge or in the midst of the wood.

The nights are now very still for there is hardly any noise of birds or of insects. The whippoorwill is not heard, nor the mosquito, but only the lisping of some sparrow.

There is a great difference between this season and a month ago — as between one period of your life and another.

— arranged from Henry David Thoreau, Journal (October 1, 2, and 5, 1851) CC0

“Merry Christmas!” said Scrooge, “What right have you to be merry? You’re poor enough.”

“Come, then,” returned Scrooge's nephew gaily. “What right have you to be dismal? You’re rich enough.”

Scrooge having no better answer ready on the spur of the moment, said, “Bah!” again; and followed it up with “Humbug.”

“Don’t be cross, uncle!” said the nephew.

“What else can I be,” said Scrooge indignantly, “when I live in such a world of fools as this? Merry Christmas! Out upon merry Christmas! What’s Christmas time to you but a time for finding yourself a year older, but not an hour richer? If I could work my will, every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart!”

“Uncle!” pleaded the nephew.

“Nephew!” returned the uncle sternly, “keep Christmas in your own way, and let me keep it in mine.”

“I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time,” returned the nephew, “when it has come round, as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!”

— Charles Dickens (Unitarian), public domain

You can feel it now: the days are longer, the sun higher in the sky at mid-day.

Something begins to emerge from winter: rising sap drips from broken branches and buckets appear on sugar maples; snow melts.

The yellow blossoms of witch hazel; green skunk cabbage in silent marshes; you can see little bits of it.

You can hear it: small birds singing once again in the morning, and at night the owls call out, searching for mates.

Don't tempt fate by saying winter's as good as over. It's not.

But there's a feeling of hope in the longer days: something new is coming.

— Dan Harper (Unitarian Universalist) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (written for central New England)

By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast — a cold wind. Beyond, the

waste of broad, muddy fields

brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen

patches of standing water

the scattering of tall trees

All along the road the reddish

purplish, forked, upstanding, twiggy

stuff of bushes and small trees

with dead, brown leaves under them

leafless vines —

Lifeless in appearance, sluggish

dazed spring approaches —

They enter the new world naked,

cold, uncertain of all

save that they enter. All about them

the cold, familiar wind —

Now the grass, tomorrow

the stiff curl of wildcarrot leaf

One by one objects are defined —

It quickens: clarity, outline of leaf

But now the stark dignity of

entrance — Still, the profound change

has come upon them: rooted, they

grip down and begin to awaken

— William Carlos Williams (Unitarian), title poem from Spring and All (1923), public domain

The voice of my beloved: behold, my beloved comes leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills.

My beloved spoke, and said unto me, Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away.

For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone;

The flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come,

And the voice of the turtledove is heard in our land.

The fig tree puts forth her green figs, and the vines with the tender grape give a good smell.

– Hebrew Bible (Song of Solomon, 2.8-13) public domain

In a Mediterranean climate, the end of the winter rains signals the coming of spring. This reading is especially appropriate for spring in Mediterranean climates, such as coastal California.

Gently I stir a white feather fan,

With open shirt sitting in a green wood.

I take off my cap and hang it on a jutting stone;

A wind from the pine-trees trickles on my bare head.

— Li Po (701-762), trans. Arthur Waley (1919) public domain

Responsive readings are set in regular type for the inital voice(s), and italics for the responding voice(s).

Look to this day! For it is life, the very life of life.

In its brief course lie all the verities and realities of your existence:

The bliss of growth—the glory of action—the splendor of beauty.

For yesterday is but a dream,

And tomorrow is only a vision,

But today well-lived, makes every yesterday a dream of happiness, and every tomorrow a vision of hope.

— anonymous late 19th century American; the version above appeared in the April, 1911, newsletter of the Bullfinch Place Church (Unitarian), Boston CC0

May the truth that sets us free,

And the hope that never dies,

And the love that casts out fear

Be with us now

Until the dayspring breaks,

And the shadows flee away.

— arranged from the Hebrew and Christian scriptures (John 8.32, Romans, John 4.18, Song of Solomon 2.17)

The core of this benediction came from 2 Thessalonians 5.14-18. This core was adapted by various people, picked up by Unitarian Universalists and adapted further; the adaptation below is by the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto. Since we Unitarian Universalists come out of the Christian tradition, our adaptation of Christian writings is not cultural misappropriation, but rather represents an ongoing evolution of that ancient tradition.

English:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the faint-hearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

Spanish:

Vete en paz al mundo

Mantén tu valentía

Sostén lo bueno con firmeza

No pagues maldad con maldad

Fortalece a los frágiles de Corazón

Apoya a los débiles

Auxilia a los que sufren

Goza de la belleza

Expresa amor con palabra y acción

Honra a todos los seres.

— trans. Guillermo Oliva

German:

Gehe mit Frieden in die Welt hinaus

Sei guten Mutes

Halte fest das Gute

Vergelte nicht Uebel mit Uebel

Staerke die Zaghaften

Unterstuetze die Schwachen

Hilf den Leidenden

Erfreue dich des Schoenen in der Welt

Gib Liebe mit Wort und Tat

Ehre alles Dasein.

— trans. Guillermo Oliva, Esa Jacobi, Nadine Kaplanov

Dutch:

Ga in vrede de wereld in

Heb goede moed

Houd vast aan wat goed is

Vergeldt niemand kwaad met kwaad

Versterk de krachtelozen

Steun de zwakkeren

Help hen die lijden

Verheug u in schoonheid

Spreek liefde met woord en daad

Eer alle wezens.

— trans. Bear Capron

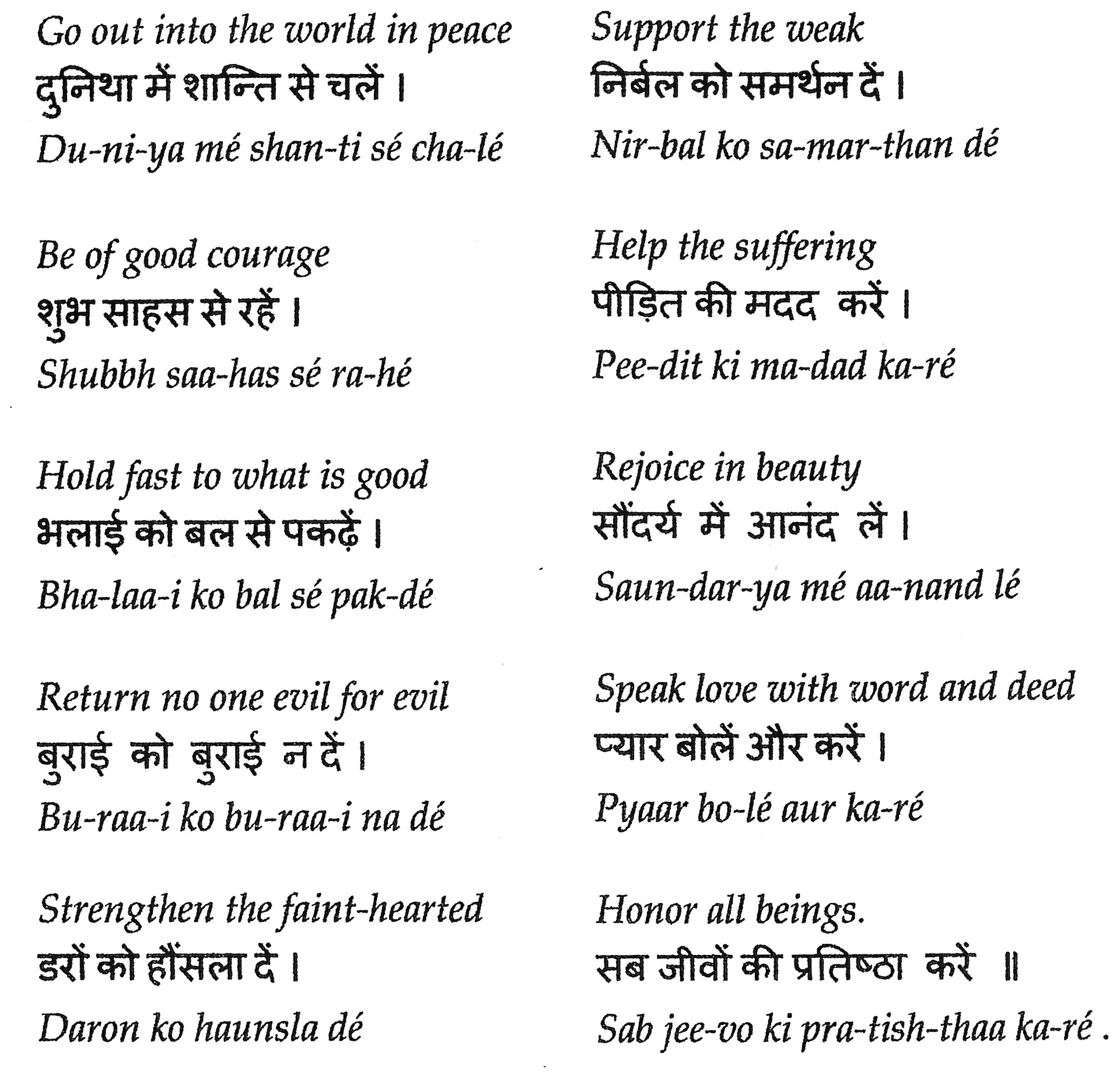

Hindi:

— translation and transliteration by Geetha Rao

The benediction and translations above are used by permission of the UU Church of Palo Alto.