A collection of Unitarian Universalist meditations, prayers, graces, etc., for you to use at home.

A. Words for lighting a chalice at home

B. Saying grace

C. Prayers for individuals and families

D. Meditations with words

E. Sabbath times: Affirmations of Unitarian Universalist identity

G. Silent meditation

F. Songs to sing

H. Seasonal meditations

This collection grew out of requests from parents for resources to help them incorporate Unitarian Universalism into their home life. Parents talked about wanting resources to fit into their meal-time and bedtime rituals, and also resources for helping children (and themselves) to become more spiritually centered. So I collected graces, or words to say before meals, prayers for bedtime or other quiet times, and meditation resources. Some parents wanted resources to support sabbath times (most often Friday night dinners) and other family times together. So I collected words for lighting a chalice, affirmations of Unitarian Universalist identity, and songs to sing together.

Why such a variety of resources? Different people may find different spiritual resources work for them. Unitarian Universalists are pragmatic people: if some spiritual resource works then use it; if it doesn't work then either alter how you're using it or try something else. And children may need different resources as they grow. We can give them a variety of spiritual resources when they are children: some of these resources will stay with them; some of these resources will be abandoned as they grow. Yet even the spiritual resources they abandon will help nurture their growth as human beings — their empathy for others, their ability for introspection, their connection to something larger than themselves.

One spiritual practice that seems to work well for most Unitarian Universalist children is the simple practice of lighting a flaming chalice. This communal practice takes but a moment, and it can help center children (and parents!). When you see UU young adults getting flaming chalice tattoos, you begin to realize how meaningful this practice is for some young people.

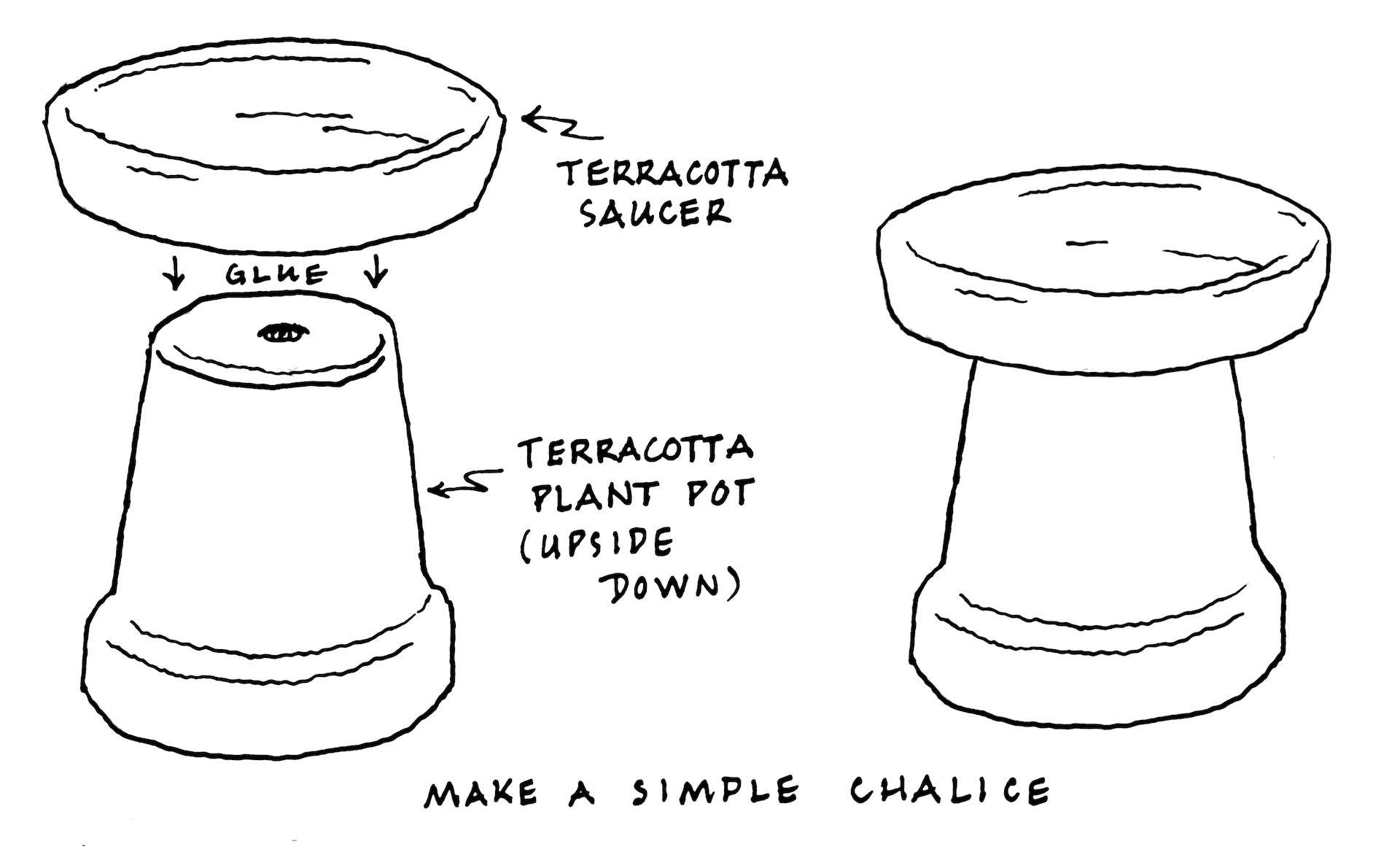

Make a simple chalice at home: Take a terracotta plant pot, turn it upside down, then glue a terracotta saucer on top of it (see the drawing below). Once the glue has set, kids can decorate the chalice with acrylic paints. For the flame, use a tea light or other small candle.

Copyright notice: You're welcome to use any of the material on this page yourself, as long as you don't republish it as your own, or sell it to someone else for profit. Individual readings may be copyright-free, public domain, or useable under the fair use doctrine of copyright law; however, using readings from this page for other purposes, e.g., in webcasts or live streams, may not be allowed. Check carefully before trying to use this material outside the home or Sunday school. Also, this page as a whole is protected by copyright, because too many pages from my Web site have been reposted by unscrupulous webmanagers.

Copyright © 2021 Dan Harper. You may not republish this page as a whole, nor may you use my commentary or my arrangement of readings, nor any other copyright-protected aspect of this page.

Lighting a flaming chalice together can be a time to pause and catch your breath as a family. Some families do this each day, often at dinner time. Some families set aside a sabbath-time (a resting time) to do this each week, perhaps on Friday evening or Sunday evening. Below are some readings you could use as you light the flame.

If you have time, after you've lit the flame and after you've heard the reading you could ask each person to say a little something about their day (or their week, depending on how often you do this). To make it easier for school-aged children, ask them to tell one good thing and one bad thing that happened today. For preschool children, you can have pictures of emotion faces and have them point to the emotion face that shows how they feel. (You can make your own sheet of emotion faces, or if that feels like too much work for a busy parent, the University of Southern Florida has a printable sheet of emotion faces designed for classroom use that you could use at home.) Middle schoolers and high school youth may not need any prompts, though sometimes even adults appreciate the structure of “Tell us a good thing and bad thing that happened to you today.”

The light of the ages has brought wisdom and truth to all peoples, in all times of human history. We light this flame to remind us to seek wisdom in our own time.

— Dan Harper CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

We light this flame to represent our liberal religion:

A religion that stands for freedom and tolerance;

A religion that believes in the use of reason;

A religion that offers hope that we can make the world better.

— Dan Harper CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Fire sends forth its far-spreading luster: bright and radiant like the Dawn.

Its splendor shines forth, and awakens our longing thoughts.

— Dan Harper CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 inspired by the Rig Veda, Book VII, Hymn X, v. 1 (as translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith)

Unitarian Universalists around the world recognize the flaming chalice —

in Romania, Australia, and the Khasi Hills of India;

in the Philippines, Canada, and the capital of Nigeria;

in Brazil, South Africa, and here in the United States.

For Unitarian Universalists around the world,

the flaming chalice is our symbol of freedom and justice.

If you're outside the U.S., substitute your own country for “United States.”

— Dan Harper CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

As we light this flame,

May the truth that sets us free,

And the hope that never dies,

And the love that casts out fear

Be with us now

Until the dayspring breaks,

And the shadows flee away.

— adapted from the Christian and Hebrew scriptures

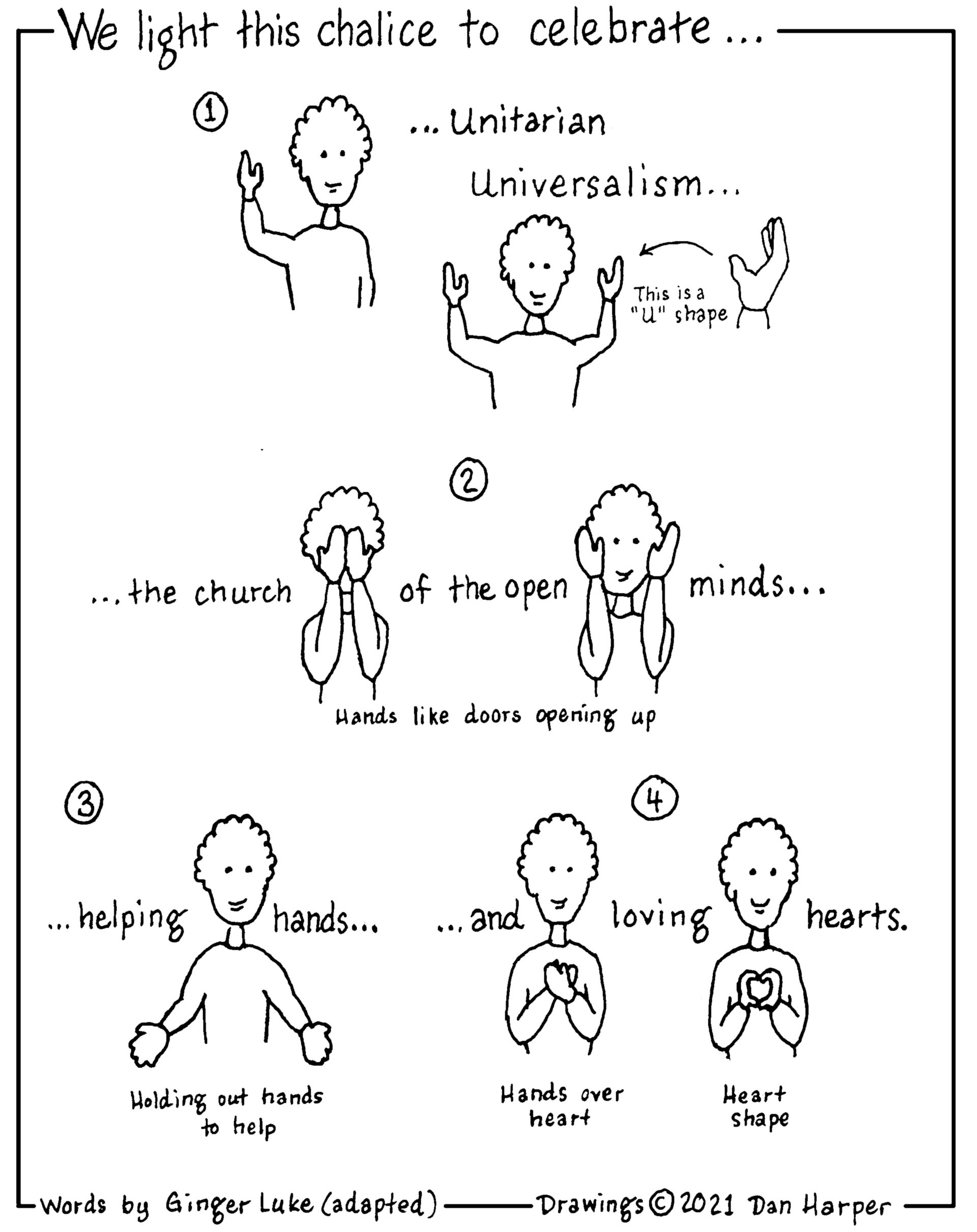

We light this chalice to celebrate

Unitarian Universalism,

the church of the open minds,

helping hands,

and loving hearts.

— adapted from Ginger Luke (Unitarian Universalist)

These are suggestions for ways to offer appreciation for your food (and for the wide universe from which it comes!) before starting your meal.

Hold hands around the table. Ask everyone at the table to say one thing they are thankful for that day.

Blessed are you, Holy One, Creator of the Universe,

who brings forth bread from the earth.

— based on an ancient Jewish prayer

Rub-a-dub-dub,

Thanks for the grub,

Yay, (God) (Goddess) (Earth)!

— from Liberal Religious Youth, the Unitarian Universalist youth movement, c. 1960. In the last line, substitute whatever works for your family.

Hold hands around the table. Say: “Let us have a moment of silence to give thanks for the food we eat.” 5 to 30 seconds of silence is about right (depending on the ages of children who are present).

We give thanks for this food,

For the plants and animals from which it came,

For the farmers and farmworkers who grew it,

For those who packed it and shipped it to us,

For the people in our family who cooked it,

To all these, we give thanks.

— adapted from an anonymous grace CC0

The sacrifice is Brahman, the ghee and grain

Are Brahman, the fire is Brahman, the flesh it eats

Is Brahman, and unto Brahman shall attain

Those who meditate on Brahman.

— from the Bhagavad Gita IV.24, trans. Edwin Arnold (1885) CC0. This passage from the Gita is said by some Hindus before meals. Emerson's poem “Brahma” may be seen as a meditation on the insight contained in this passage of the Gita.

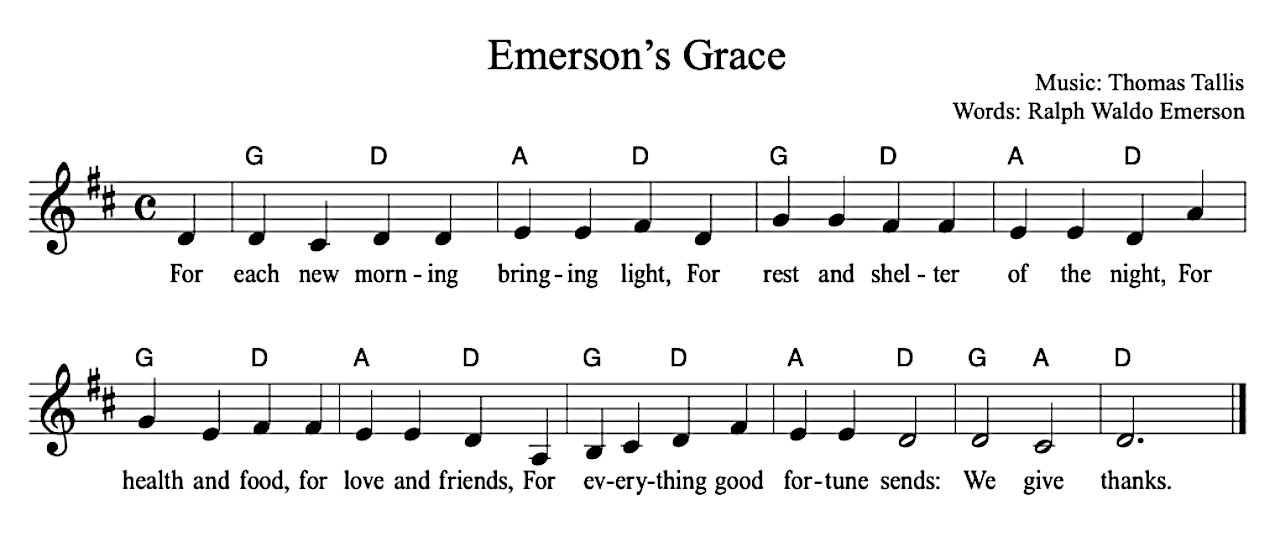

For each new morning, bringing light,

For rest and shelter of the night,

For health and food, for love and friends,

For everything good fortune sends,

We give thanks.

— adapted from Ralph Waldo Emerson CC0. These words may be sung to a tune by Thomas Tallis, given in the audio files and sheet music below.

Direct link to the audio file.

Many people find words helpful in expressing their religious identity, and in guiding their religious journey. These poems and short readings can serve as prayers for all ages. I know an older Unitarian Universalist who was taught “Outwitted” in her childhood church and still can recite it to this day. You never know what young people will hold on to as they get older.

I am only one.

But still I am one.

I cannot do everything.

But still I can do something.

And because I cannot do everything

I will not refuse to do the something that I can do.

— Everett Edward Hale, 19th C. Unitarian minister

They drew a circle that shut me out —

Heretic, a rebel, a thing to flout.

But Love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle that took them in.

— Edwin Markham, poet, teacher, Universalist

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto its nest again,

I shall not live in vain.

— Emily Dickinson

I will be truthful.

I will suffer no injustice.

I will be free from fear.

I will not use force.

I will be of good-will to all people.

— attributed to Mahatma Gandhi

If you can renew yourself one day,

You can renew yourself each day,

Again and again renew yourself.

— Confucius, The Great Learning, trans. James Legge CC0

Look to this day!

For it is life, the very life of life.

In its brief course lie all the truth

And reality of your existence:

The bliss of growth,

The glory of action,

The splendor of beauty;

For yesterday is already a dream,

And tomorrow is only a vision;

But today well-lived,

Makes every yesterday a dream of happiness

And every tomorrow a vision of hope.

— late 19th C. prayer reprinted in The Beacon Song and Service Book (Unitarian), 1925

For children with the help of their parents/guardians:

Tonight I am thankful for... (say some of the good things that happened to you today)

And I am sorry for... (talk about the things you feel sorry for doing or saying)

Tomorrow I hope for... (things you hope for and how you think you can make them happen)

To pray is but to cross a sill

From crowded rooms, their noise and glare,

Into the star-lit calm of night,

That all the while was waiting there.

— Frances Whitmarsh Wile (Unitarian), c. 1910. Perhaps this might help children who find themselves afraid of their dreams, or the dark, or being alone.

Now I end another day

Thinking of my work and play,

Knowing I have done my best

I will sweetly sleep and rest.

And I trust that loving care

May enfold me everywhere,

And may keep me pure of heart

As I try to do my part.

— Henry S. Kent, c. 1900

Lead us from death to life, from lies to truth.

Lead us from despair to hope, from fear to trust.

Lead us from hate to love, from war to peace.

Let peace fill our hearts, our world, our universe.

Peace. Peace. Peace.

— adapted from the Upanishads

Universal love, with us always,

Your name is truth and goodness.

May love rule the earth,

As love rules in my heart.

Grant the food we need today,

And forgive us when we fail,

As we forgive those who fail us.

May I not be tempted into wrong-doing,

But may love watch over me, and over us all.

— traditional Jewish prayer, adapted by early Christian communities, further adapted by Dan Harper CC0

How is a meditation with words different from a prayer? Perhaps prayer is more often directed to a force or concept or being outside oneself, while meditation is more often directed to one's own inner world. But there is much overlap between the two, and it can be hard to draw a clear line between them.

The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world, and dances in rhythmic measure.

It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the earth in numberless blades of grass, and breaks into tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers.

It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and flow.

I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this world of life.

And my pride is from the life-throb of ages dancing in my blood this moment.

— Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore was affiliated with the Brahmo Samaj religious movement in late 19th C. India, a movement that had a large influence contemporary Unitarianism.

I have just seen a beautiful thing

Slim and still,

Against a gold, gold sky,

A straight cypress,

Sensitive

Exquisite,

A black finger

Pointing upwards.

Why, beautiful still finger, are you black?

And why are you pointing upwards?

— Angelina Grimke

One little star in the starry sky,

One little beam in the noon-day light,

One little drop in the river's might,

What can it be, O what can it do?

Each little child can some love-work find,

Each little hand, and each little mind,

All can be gentle and useful and kind,

O what can I be, and what can I do?

— Susan Coolidge, late 19th C., public domain. This poem is aimed at preschoolers and kindergarteners. Older children may prefer the next poem, which expresses a related sentiment.

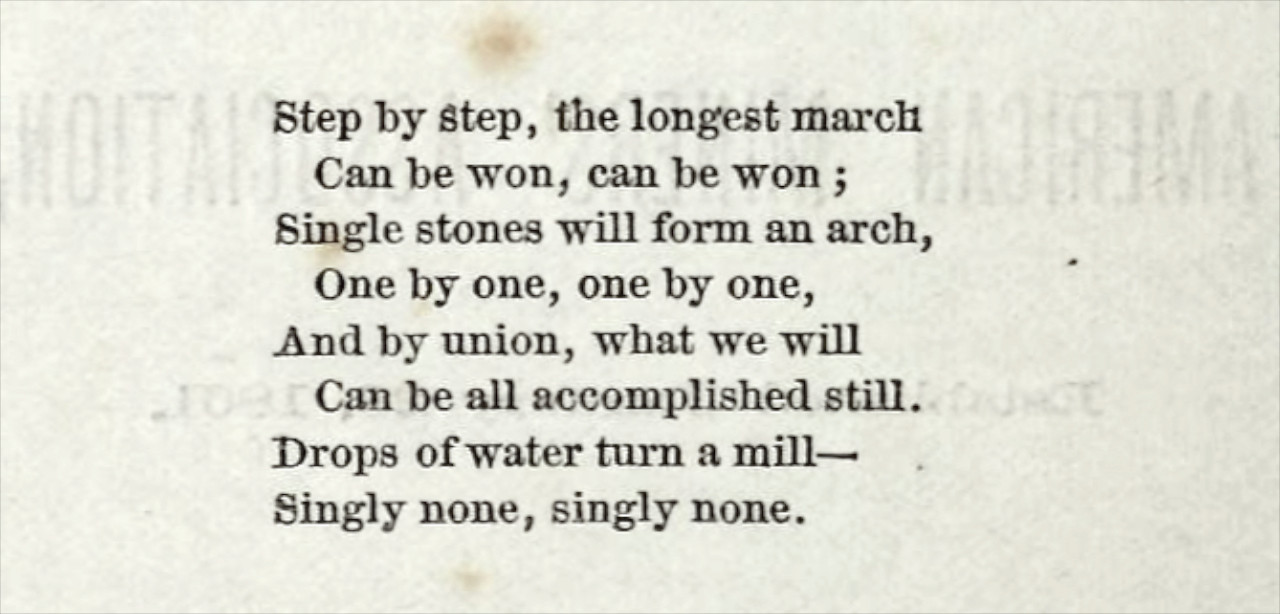

Step by step, the longest march

Can be won, can be won,

Single stones will form an arch

One by one, one by one,

And by union, what we will

Can be all accomplished still.

Drops of water turn a mill—

Singly none, singly none.

— poem from Constitution and Laws for the Government and Guidance of the American Miners' Association (1864), public domain

Many excellent poems can serve as meditations. The following copyrighted poems could serve as meditations, and many of them address powerful topics such as justice, the purpose of God or of life (if any), and the meaning of life. These poems are most suitable for teens and adults.

God by Langston Hughes, which says it might be better to be human than to be God.

I’m Not a Religious Person But by Chen Chen, a meditation on pop culture and religion.

In California: Morning, Evening, Late January by Denise Levertov, an ecojustice poem.

Mancunian Taxi Driver Foresees His Death by Michael Symmons Roberts, a poem about climate change (recommended by a high school-aged youth).

my dream about being white by Lucille Clifton, a brief but powerful meditation on race. Many of Clifton’s poems make excellent meditations; more of her poems.

Sanctuary by Jimmy Santiago Baca, a poem about immigration.

Thank You by Ross Gay, a poem of gratitude (but not of easy gratitude).

Readings for your family to affirm their identity as Unitarian Universalists.

May faith in the spirit of life

And hope in the community of earth

And love of the sacred in ourselves and others

Be ours this day and in all the days to come.

— affirmation of First Unitarian in New Bedford, c. 1975 (anonymous, Farley Wheelwright?)

I will strive toward high ethical and moral standards in my personal life and in my life in the wider community.

I will work for the understanding and promotion of a religion of love, assuming a spirit of cooperation and tolerance towards other religious groups.

I will commit myself to keep formulating my own religious beliefs according to my individual needs, the needs of the world around me, my conscience, and my degree of maturity.

— from First Unitarian Church, New Bedford, Mass., c. 1920

Being desirous of promoting practical goodness in the world, and of aiding each other in our moral and religious improvement, we come together — not as agreeing in opinion, not as having attained universal truth in belief or perfection in character, but as seekers after truth and goodness.

— Unitarian Universalist Society of Geneva, Illinois, 1842 (adapted)

Love is the doctrine of this household,

The quest for truth is its sacrament,

And service is its prayer.

This is our great covenant:

To dwell together in peace,

To seek the truth in love,

And to help one another

To the end that all souls

shall grow into harmony with the divine.

— anonymous, public domain; as used at First Parish in Lexington, Massachusetts, c. 2000 (adapted)

We affirm our faith in —

Universal love, eternal and all-embracing;

Spiritual leadership arising in each generation;

The supreme worth of every human being;

The authority of truth, known and to be known;

The power of people of good will and sacrificial spirit to overcome evil,

and to progressively establish a world of goodness and love.

— adapted from the 1935 Universalist affirmation of faith

Some people prefer a spiritual practice that focuses on silence. It's important to remember, though, that not everyone does well with silent meditation, and in fact some people even experience negative effects from silent meditation practices. Nevertheless, while a regular practice of silent meditation is not for everyone, knowing how to meditate in silence is a worthwhile skill to learn.

Adults and youth who want to learn perhaps the simplest and easiest meditation technique can read The Relaxation Response by Herbert Benson. While Benson's technique is based in Buddhist meditation practices, his meditation technique has been secularized to a large extent. Various religious traditions have specific forms of silent meditation that can be learned. Examples include Buddhist mindfulness practices, Christian centering prayer, Confucian quiet sitting, etc.

The two silent meditation practices that follow are suitable for Unitarian Universalist children. In my experience, these two practices rarely result in negative experiences.

Probably best for use with young children and school aged children. Light a candle (or a flaming chalice), perhaps using some of the words for lighting a chalice (see above), and then just sit in silence for two or more minutes watching the candle flame. (If you light a small candle like a birthday candle, you can watch it until it burns all the way down). Often even young fidgety children who resist the idea of silent meditation will like this practice.

You could introduce this practice to children by talking a little about how Henry David Thoreau lived in his cabin at Walden Pond, and how sometimes on a pleasant morning he would sit on his doorstep for hours at a time, lost in the beauty of the natural world — or, as he put it, “rapt in a revery.” His idea of losing yourself in silent appreciation of the natural world makes an authentically Unitarian Universalist meditation practice. It is worth noting that Thoreau’s cabin was also a station on the Underground Railroad, so his nature meditation was deeply connected to social justice work.

Collect some natural objects, such as pretty stones, dried leaves of grasses, flowers, pine cones, etc. Ask the child/ren to take one of these natural objects, one that appeals to them, and hold it in their hands; look at every detail; you don't have to think of anything else.

Then sit in silence for 1-2 minutes while they look. You can work up to longer times. Older children may sit for as long as 10-20 minutes.

You can end the meditation by saying: “Let the beauty we love, be what we do.”

When weather permits, this kind of meditation works even better outdoors. When you’re outdoors, children can look around for their own natural object. Alternatively, you can have them listen to all the sounds of the outdoors, and at the end of your time of silence you can share all the sounds you heard (wind in the trees, birds, cars, perhaps animals, etc.). Or you can lie at the foot of a big tree and gaze up into its branches for a time of silence, as yet another form of outdoor meditation.

With roots in the Unitarian Transcendentalists, this may be the only form of silent meditation that is distinctly Unitarian Universalist; most other forms of silent meditation have roots in other religious traditions.

The Relaxation Response by Herbert Benson M.D. (1975) attempts to separate the technique of silent meditation from religion, and provides simple clear instructions for meditating. It's available at many libraries, or for online borrowing at the Internet Archive.

Singing is a wonderful group spiritual practice for families. If you're new to singing, start off by singing songs you know well. The lyrics matter less than the simple act of singing together.

The best source for songs with Unitarian Universalist lyrics are the two Unitarian Universalist hymnals, Singing the Living Tradition and Singing the Journey. Both these books are available from the bookstore of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Search Web sites like Spotify and Youtube for recordings of the hymns and songs in these two hymnals.

If someone in your family plays the guitar or ukulele, the hymnals aren't much help. Either the chords are too difficult for the average player, or there's no chords at all.

Fortunately, some of the songs in the hymnals appear with chords in Rise Up Singing and Rise Again, two popular songbooks edited by Peter Blood and Annie Patterson. The Rise Up Singing Web site has learning videos, another reason to try these books. In the list below, the numbers in parentheses refer to the page number in Rise Up Singing (RUS) or Rise Again (RA) with lyrics and chords for that song. Note that the lyrics in RUS and RA may give more traditionally Christian words than the UU hymnals.

Singing the Living Tradition

16, 'Tis a Gift To Be Simple (47 RUS)

21, For the Beauty of the Earth (153 RUS)

38, Morning Has Broken (154 RUS)

108, My Life Flows on in Endless Song (43 RUS)

169, We Shall Overcome (63 RUS)

170, We Are a Gentle Angry People (218 RUS)

205, Amazing Grace (92 RUS)

305, De Colores (152 RUS)

Singing the Journey

1020 Woyaya (RUS 120)

1021 Lean on Me (66 RUS)

1053 How Could Anyone (85 RA)

1064 Blue Boat Home (42 RA)

1074 Turn the World Around (139 RA)

Come Sing a Song with Me, no. 346 in Singing the Living Tradition, has been a perennial favorite with children (and adults). The chords in the hymnal aren't too hard, but for easier chords, capo 2 and play:

G - - - / C - - D7 / G - - - / Am D G - //

D - G - / D7 - G - / D - G Em / Am D G - /

Some Unitarian Universalist singer-songwriters have also written songs expressing Unitarian Universalist values that families might enjoy singing together. UU singer-songwriters include Pete Seeger, Utah Phillips, Malvina Reynolds, and Ysaye Maria Barnwell. To get you started, here's half a dozen songs by UU singer-songwriters found in Rise Up Singing or Rise Again:

“Breaths,” Ysaye Maria Barnwell, 267 RA (1001 in Singing the Journey)

“Bells of Rhymney,” Pete Seeger, 222 RA

“Turn Turn Turn,” Pete Seeger, 228 RUS

“God Bless the Grass,” Malvina Reynolds, 35 RUS

“Magic Penny,” Malvina Reynolds, 240 RUS

“Singing through the Hard Times,” Utah Phillips, 139 RA

Seasonal meditations can help you focus on what’s going on around you — in the both the human and non-human world — as the wheel of the year turns. Seasonal meditations may be most attractive to families with interests in ecojustice or Paganism. Just remember that the wheel of the year is different depending on where you live; if you live in the San Francisco Bay Area of California, your winter readings will be about the rainy season, not about snowfall and frozen ground. To find seasonal meditations for your area, you can look for poems written by poets who live in your area.

Or why not try writing your own seasonal meditations? Below are some examples of seasonal meditations that I wrote. I wrote the first four in 2002-2003 for central New England, and the second group I wrote in 2010-2015 for the Peninsula in the Bay Area, California. If I can write seasonal meditations, so can you!

Copyright © 2021 Dan Harper

Athol, Massachusetts

January: Winter

The crystalline light of late January

filters down to us through cold air,

reflects off snow and ice, barely

warms our face. In the depths of winter,

it’s hard to remember spring will come

one day. But in the mean time,

that cold clear light shows us

a landscape stripped to essentials.

We feel that we can see things

as they really are, not hidden

behind myth and superstition and

fairy tales. It is winter reality.

March: Spring

Now you can feel it: the days are longer,

the sun higher in the sky at mid-day.

Something begins to emerge from winter:

rising sap drips from broken branches and

buckets appear on sugar maples; snow melts.

The yellow blossoms of witch hazel;

green skunk cabbage in silent marshes;

you can see little bits of it.

You can hear it: small birds singing

once again in the morning, and at night

the owls call out, searching for mates.

Let’s not tempt fate by saying,

winter’s as good as over. It’s not.

But now you can feel hopeful.

Something new is coming.

June: Summer

At nine in the evening, you can still

sit outdoors and read a book; the sun

just below the horizon then, but still

it sheds enough light to see clearly.

The light fades a little more; stillness

emerges from the trees and bushes;

not silence, but a stillness filled

with faint sounds of neighbors talking,

the girl jumping on the trampoline

across the way, the quiet chittering

of a few chimney swifts flying high above,

headed home, a faint rustle of leaves

as the evening breezes start up. Still

the sky has that faint tinge of blue

low in the west; a star now appears, or

no, a plane, thousands of feet above,

no sound of it down here, just

landing lights pointing who knows where;

now a star, and another; you can barely see

a bat begin her nightly hunt. The book

lies forgotten this midsummer’s evening

in that stillness where dreams begin.

November: Autumn

Towards the end of autumn, as days grow short

the sun never gets very high above the horizon.

Already the first snow has come, and all the trees

are bare, except for a few stubborn oaks.

If you haven't finished raking up the leaves

by now, it's too late. Give up for the year!

Late autumn is made for idleness: it's made

for sitting in the long, dark evenings;

for thinking of nothing and everything; for

memories. Do what’s necessary, but nothing

more. Sit in idleness. Stare at long shadows.

That is how the long nights of late autumn

are meant to be used.

Copyright © 2021 Dan Harper

San Mateo, California

September: Wildfire season

We were awakened in the middle of the night by the smell of smoke. We got up in the dark. Our building was not on fire. Where was the smell was coming from? Maybe the neighbors left a fire burning in their fireplace overnight, and the slight breeze blew it into our house? The next morning we heard that thousands of acres were burning 70 miles north of us; the smoke we smelled was from those fires.

Tonight the light was rosy with a yellow tinge. I went up to where you can look out at San Francisco Airport, and watched a couple of jetliners land. A bank of fog stretched from the Golden Gate across the Bay towards Oakland; an avalanche of fog curled over the top of San Bruno Mountain; the fog was several hundred feet above me, pushed upwards as it moved through Crystal Springs Gap. A pair of White-tailed Kites hovered overhead, silhouetted against the bright low clouds; they worked their way down the hill, coming to a hover every minute or so, until they disappeared behind some trees. The rosy glow from the sunset really was lovely, even knowing that lovely redness came from wildfire smoke.

December: Rainy season

It’s so green,

I said, as

we drove past

San Bruno

Mountain. Yes,

said my friend,

enjoy it

while you can.

The rain came

and went. Light

rain, heavy

rain, no rain.

The water

rushes down

creeks to the

Bay. Then stops.

Then months with

no rain, none

at all. Sun.

More sun. And

San Bruno

Mountain will

turn dusty-

brown and dry.

It’s so green,

I said to

myself. I

admired it

for an in-

stant, then fo-

cused back on

the freeway.

February: Season of the golden haze

We walked down to the edge of the water. The hills across the bay are now a soft green. The setting sun glinted off windows of houses far up in the Oakland hills. And a beautiful golden haze hung over the waters of the bay.

It's the golden haze again. This is how it’s been for the past week: cold, still air has settled down over the area, trapping pollutants in the wide bowl formed by the mountains surrounding the bay. The people who monitor air pollution say the air quality is unhealthy because they have been detecting high levels of fine particles. That’s what has caused the golden haze.

It’s beautiful, we said to each other. We kept walking, watching the shorebirds, and the play of light on the water.

May: Apricot season

Carol turned the car into a roadside fruit stand. Some of the apricot trees hung over the parking area, and the owner of the stand charged just fifty cents a pound for fruit we picked from the parking lot.

We took home ten or fifteen pounds of apricots, and the kitchen was taken over by jam-making. On the counter near the stove were pectin, canning jars, jar lids, and bags of sugar. On the stove sat a big pot for cooking fruit and another big pot for sterilizing jars. On the counter on the other side of the sink was the big bag of fruit waiting to be processed. Before long, all that fruit had been cooked into jam. But apricot season wasn’t over yet, and Carol got more cheap apricots at the farmer’s market, and made more jam. Jars full of deep orange apricot jam sat cooling on the kitchen counter, and every once in a while one would make a little “tink” sound as the lid sealed into place.

Apricot season will soon come to an end. Soon there will be no more bowls full of apricot pits in the kitchen, waiting to be put on the compost pile; there will be no more jars cooling on the counter, and no more “tink” sounds at unexpectedly moments; no more orange drips of jam in odd places. The kitchen will return to normal. Three dozen jars of jam will sit quietly in the kitchen closet waiting to be given away and eaten. And we’ll wait for apricot season to return again next year.

July: Fog season

I came vaguely awake early this morning as a city bus turned the corner at the traffic light below our bedroom. The summertime fog had returned at last. The light was dim and diffuse, and I knew that the fog was hanging a few hundred feet over the city, blocking the sun. The cold water was welling up from the depths of the Pacific on the other side of the Coastal Range, once again making a huge fog bank in the early morning. The growing warmth inland heats the air over the Central Valley, and draws the fog through the passes. On the coast side of the hills to the west, the fog lies at ground level, but is pushed up by the Coastal Range to form low clouds.

The city is cool and gray and dim and delightful. By mid-day, the sun will burn the fog away, revealing once again the relentless summertime sunshine. But tomorrow morning will again be dim and cool.