Still under development.

Change is inevitable. Demographic changes and economic changes typically have effects on congregations. Congregations may also wish to initiate change on their own, e.g., increasing member giving. By managing change, we hope to meet the external changes imposed on our congregations while meeting our own internal goals, and all the while behaving humanley and putting people first.

Measuring Change — Metrics

Effecting Change

Humane Change Management

The first step in managing change is learning how to measure change. In order to measure change, first you collect data, then you analyze the data.

Collecting data is challenging, because it requires meticulous attention to detail over a period of years, through changes in lay leadership and through changes in paid staff. Make data collection become a habit in your congregation. As the saying goes: “The congregations that count — are the congregations that count.”

I recommend getting in the habit of tracking Four Important Numbers:

You'll also want other numbers such as financial data and historical data. The devil is in the details, so I'll treat each of these categories separately below.

This number generally proves to be the most difficult number to calculate accurately because of two big problems.

First Problem: Membership lists may be poorly maintained. Your congregation's bylaws should specify exactly who is a member, and who is not a member. (If there is ambiguity in your bylaws about who is, and who is not, a member, then stop here, and fix that problem immediately.) Yet while most bylaws clearly specify who is a member, it's a rare congregation that follows their bylaws consistently year after year. For example, many congregational bylaws state that members must make an annual financial contribution, but many congregations fail to purge their membership lists of those who have not made an annual financial contribution. Someone has to take responsiblity for maintaining the membership list.

Second Problem: Criteria for membership may too loose, OR too strict. Where membership criteria are too loose, it takes very little effort to become a member, with the result that the membership list becomes cluttered up with people who have no commitment to the congregation — the easiest way to address this problem is to purge your membership list of deadwood each and every year. Where membership criteria are too strict, people are purged from the membership rolls when they should not be, e.g., to save money on denominational per-member fees — the best way to address this problem is to follow membership criteria in your bylaws to the letter when purging your membership list.

Ultmately, you want a list of people who have made a membership commitment to your congregation, in whatever way your bylaws define membership. The logical time to calculate the membership number is in late November, a month before you have to report report membership numbers to the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA). By starting in late November, you'll have time go over your membership list carefully before submitting data to the UUA.

A “pledge unit” can be defined as an individual or household that pledges an annual donation to the congregation. Tracking pledge units is important for at least three reasons. First, pledges typically represent the primary revenue stream for Unitarian Universalist congregations. Second, an individual or household that donates money on a regular basis is demonstarting a tangible commitment to the congregation. Third, the pledge unit number supplements the number of congregational members, because it captures people who are committed to the congregation but choose not to become members. For households that make annual contributions but refuse to pledge, you can choose whether they get counted as pledge units or not; just be sure to count them the same way every year, so you collect consistent data over time.

Ultimately, you want a list of individuals and households that make an annual financial contribution to your congregation. You can keep a running count of pledge units, but you should also make an annual count one month after the formal end of your annual pledge drive (allowing a month for late pledges to come in).

The problem here is how you define enrollment. If a child is enrolled when their parent fills out a registration form, it's easy to artificially inflate enrollment by chasing down every parent that ever shows up on a Sunday morning and getting them to fill out a registration form. Instead, consider a child or teen to be enrolled if their parent has filled out a registration form and the child has attended Sunday programs at least once from late August through December 31 OR parents have not completed a registration form but the child or teen has attended at least three times from late August through December 31.

There are exceptions to this general rule. Since high school teens may consider themselves a part of the congregation, yet don't attend youth group or classes, I count high school teens as enrolled if they show up on campus at least once from summer through December 31 (e.g., serve on a committee, take part in social action, etc.), or otherwise express connection to the congregation. Infants whose parents are members of the congregation are counted as enrolled even when their parents neither register them nor bring them on Sunday morning. Children with serious disabilities that preclude them from taking part in religious education programs are considered on a case-by-case basis; if we have some kind of ministry to them or to their parents, they are counted as enrolled.

Ultimately, you want a list of children and teens who feel connected to your congregation, to whom the congregation has a ministry. You can keep a running count of enrollment, but it will be more accurate if you do it once a year in December, just before you have to report this number to the UUA.

A congregation's primary “product” is typically Sunday programming. Certainly the biggest part of the budget, and the majority of staff time and volunteer time, goes towards Sunday programming. Therefore, average annual Sunday attendance is an important number. It's also a difficult number to calculate because it requires constant and consistent data collection.

Who gets counted: Typically, Sunday attendance consists of everyone who sets foot on campus on Sunday to attend either your worship service(s) or participate in your religious education programs or participate in other programs such as a weekly forum. If you have a Saturday evening service, that should be counted as part of your Sunday attendance.

Double counting: If a big chunk of people attend two programs on Sunday (e.g., there are 20 people who attend both Forum and the worship service) you'll have to decide whether you care if you double count them. In the example given, if it's a fairly consistent percentage of Forum attendees who attend both the Forum and the service, then you could use a simple multiplier on Forum attendance (e.g., 0.5) to estimate the number of unique attendees. On the other hand, you'll probably want to ignore the two or three people who attend both of your services; similarly, you probably won't want to track down the two or three people who are on campus but never make it into the service or the Forum or religious education; besides, these two groups usually just about cancel each other out.

Counting in-person attendance at worship services and weekly Forums: This is fairly straightforward. Usually, the best time to count is at the beginning of the sermon. Whoever does the count simply stands in the back of your auditorium, and counts everyone they see. Counting programs like a weekly Forum is similarly straightforward — do your count in the middle of the program, when you typically have the highest attendance. A bigger challenge is motivating volunteers to make an accurate count every week, and to record it, but usually you can impress upon people how crucial it is to have this information. If a volunteer forgets to make a count, it's OK to estimate attendance, and/or to interpolate a figure based on attendance the same week of the previous year, and with reference to the previous and succeding weeks.

Counting attendance for religious education: This is more complicated, because you have to count each separate class. Two solutions suggest themselves: one is to have a single volunteer or staffer go around to each classrom to make a count; and the other is to motivate all classroom teachers to take attendance for some compelling reason, such as keeping a list for emergency evacuations or for COVID contact tracing.

Counting online attendance: This can be a bit of a challenge. Online meeting platforms like Zoom show you how many people are logged in at any given time, so you can monitor for the highest attendance. Other platforms, like Facebook, make it more difficult to know how many viewers are actually watching. And if you're livestreaming to several platforms, you'll have to monitor each one to come up with a total. Figure out the best solution you can, and count in a consistent manner every week.

Recording data: Create an online spreadsheet, using something like Google Sheets, to collect data from all these individual counts. (Some church databases allow you to track these numbers, but spreadsheets can provide more flexibility when it comes time to analyze.) Create a spreadsheet that allows you to track attendance at each program separately, e.g., separate columns for each worship service, Forum, and religious education. Then you'll be able to watch attendance trends in each separate program, while also tracking total weekly attendance.

For our congregation, I created a main attendance spreadsheet as just described. In addition, I also created a separate religious education attendance spreadsheet that collects data for each class, and also separates out adult teachers and child/teen attendance for each class. Each congregation will probably do things a little bit differently, depending on the Sunday programs they offer, and depending on how detailed their data collection may be.

Ultimately, you want the average number of people who use your congregation's primary public ministries and services. Because there are many variable that can affect attendance (e.g., weather, seasonal variations, etc.), it is wise only to pay attention to annual averages. The best time to calculate your annual average attendance is in December, just before you have to submit this number to the UUA.

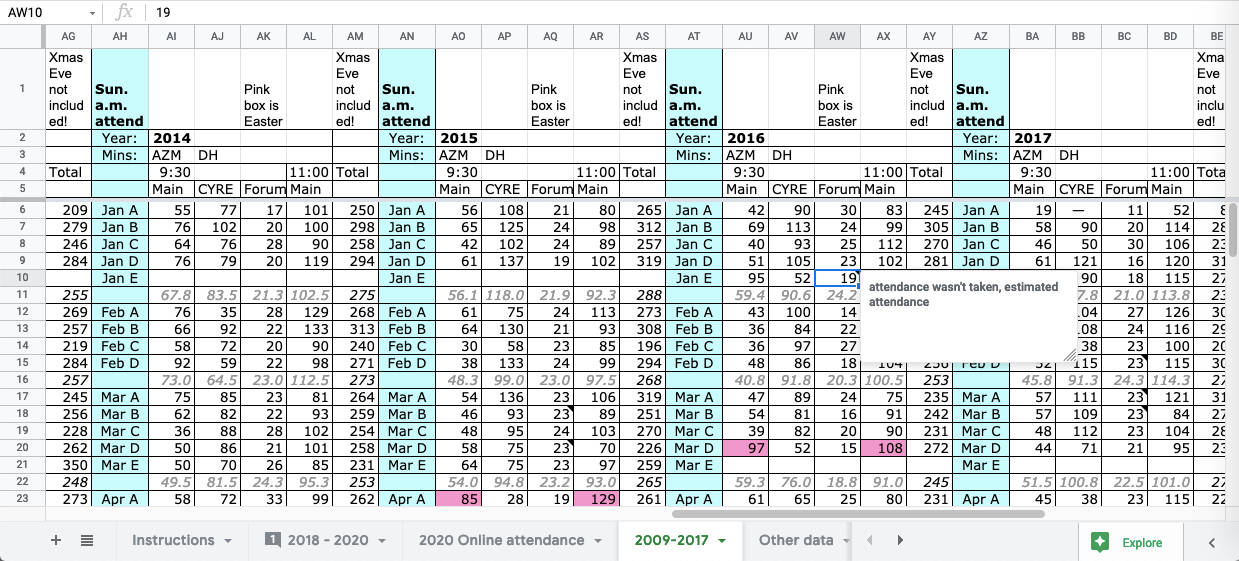

The screenshot above shows the online attendance tracking spreadsheet I've been using for over fifteen years now. Each year has separate columns for the services, religious education, and the Forum. To allow tracking from year to year, each month has rows for five weeks, labeled A, B, etc.; when there are only four weeks in a month, the fifth row is left blank. Each month is followed by a row with monthly averages. The bottom rows of the spreadsheet (not shown) give annual averages; annual averages for the church year (July 1-June 30) are also given in rows between June and July. Note the highlighted cell has a note indicating that attendance wasn't taken, so the number in the cell is an estimate.

The screenshot above shows an online attendance tracking spreadsheet for religious education classes. Both online and in-person classes are tracked. Morning classes are given separate columns from afternoon and evening classes and programs (not strictly necessary, it just makes it easier to see). Teachers/advisors are tracked separately from children/teens. This level of detail may be more than you want to bother with, but it allows us to drill down deeper into the data when doing analysis.

Financial data: Your congregation's Treasurer, Bookkeeper, and Finance Committee will automatically collect data including: annual revenue, annual contributions from members/friends, annual expenditures on staff, annual expenditures on operating budget, annual expenditures on capital projects, and so on. This data must be collected as an ordinary part of the congregation's financial management, and so will not require any special effort to collect.

Surveys: Some types of data are best tracked through surveys. For example, race, gender, sexual orientation, etc., can be impossible to determine accurately in any other way. However, be warned that creating a useful survey, then collecting data from that survey, can be incredibly challenging. Let's say you want to determine your congregation's racial make-up. If you survey just your members, you'll leave out non-member participants including children and people who pledge but aren't members. If you survey members and non-member participants, you may wind up surveying people with little commitment to your congregation. In short, it can be very difficult to know whom to survey, and where to draw the boundaries of who's in and who's out of the congregation. Then, too, for a survey to be useful, you need the highest participation rate possible. If you're tracking the racial make-up of a predominantly white congregation and you miss surveying even a few nonwhite congregants, you will greatly decrease the accuracy of your survey.

If a survey is designed carefully, executed carefully, and subjected to careful statistical analysis it may be reasonably accurate — but there are very few people who have the specialized skills to create and carry out accurate surveys. Therefore, if you carry out a survey, expect error rates on the order of 10 to 25 percent, or even more. You'll have to decide if the low quality of the data is worth the effort it takes to obtain it.

Historical data: Ideally, you'll also dig up any historical data you can. Even if there are gaps in the historical data, even if you think the data collection process was less than perfect, historical data can be useful when you're trying to track trends. Since membership, pledge units, religious education enrollment, and average annual attendance get reported to the Unitarian Universalist Association, you can find this historical information on the Data Services section of the UUA website. Yes, it's better if you have records of detailed data, but the numbers reported to the UUA are still very helpful. Some authorities suggest collecting fifty years of detailed historical data. That way, you can correct for outside forces like recessions and economic downturns, and you can also look at how the congregation responded to staff changes (e.g., new minister, etc.). However, any historical data is better than none — collect what you can.

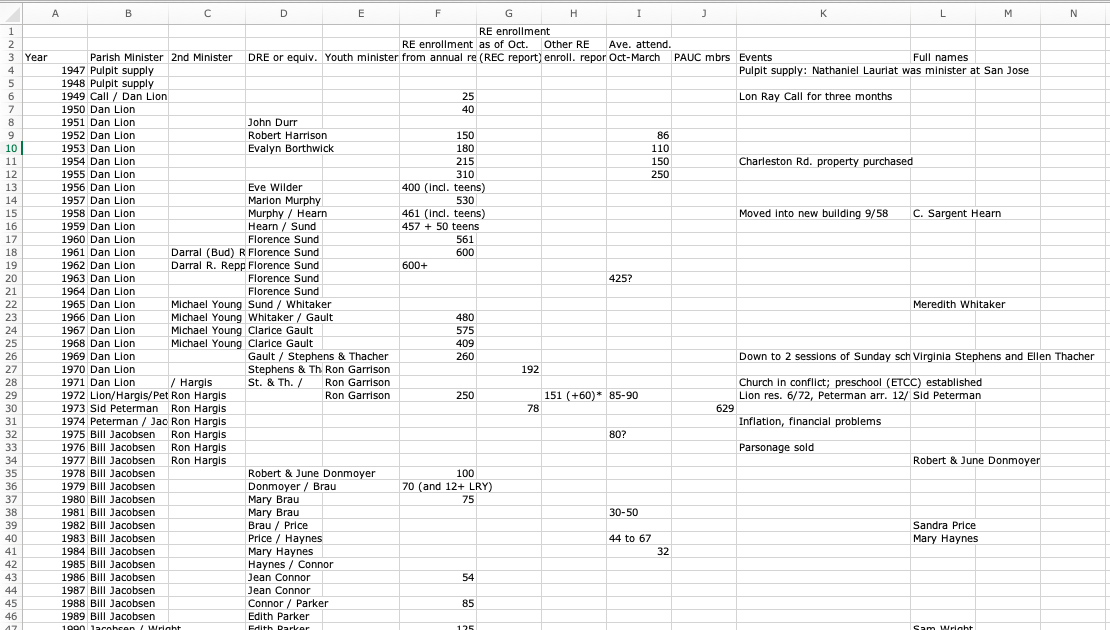

The screenshot above shows a spreadsheet designed for collecting historical attendance data for a religious education program. Most of us can't spend all our time digging through old records, but with a spreadsheet like this, when you do happen to run across historical attendance data, you have a place to store it. (Staff members are listed in columns B-E to help determine dates of undated documents.)

Now that you've collected data, you can begin to analyze it. What analysis you choose to do will depend in large part on what goals you're trying to reach. Here are some obvious possibilities to get you started:

Drilling down in your data can also provide insights. For example, say you're trying to determine if you need to put an addition on your building. Considered by itself, average annual attendance won't provide the information you need to make a sound decision. Drill down into the data to look at how many people are using each room at different times during the day on Sunday: how many children in each classroom, how many adults at each Sunday worship service, how many Forum participants, etc.

Creating graphs and charts can help you communicate your findings. Graphs and charts are especially useful for showing changes over time. Since it can be difficult to find historical data, you will often have gaps in the data, leading to discontinuities in the graphs. If other evidence (written accounts, etc.) provide a sense of what attendance might have been during the gaps in your data, go ahead and add in estimated trend lines; but if you have no other evidence, don't try to create fake trend lines.

The screenshot above shows a sample attendance graph. I created this graph when doing historical research of the Unitarian church that existed in Palo Alto from 1905 to 1934. Records were fragmentary, but I was able to find attendance data in denominational reports, as well as in the few remaining documents from that old church. Even with the large gaps in data, the graph provides a vivid depiction of the church's membership and attendance trends. For example, you can see very clearly how the combination of a major congregational conflict and the influenza epidemic depressed attendance in the church around 1918-1919.

One good strategy for effecting change is to begin by determining what you'd like to change; then measuring progress as you work towards your goals; changing course while necessary; and celebrating succes or analyzing failure.

Not many Unitarian Universalist congregations take kindly to autocratic or oligarchic rule. Therefore, when you're determining what you'd like to change in your congregation, you should plan to have a process that allows for input from all affected stakeholders. Big goals that involve the whole congregation (e.g., building a new building, doubling the size of the congregation, etc.) should involve as many people as possible. Small goals that affect a limited number of people (e.g., doubling the number of small ministry groups, renovating classroom spaces, etc.) can involve fewer people in the goal-setting process.

Here it may be helpful to distinguish “goals,” which may be very broad, vague, aspirational, and as a result hard to work towards without getting overwhelmed — from “objectives,” which are carefully defined, specific, and as a result easy to measure progress towards completing. Measurable objectives can get you to your aspirational goals. For example, your congregation may have the aspirational goal of becoming racially diverse, but if you start out 95% white, that may seem like an impossible goal to reach. So you begin with objectives to help move you towards your goal. In this example, your near-term objectives could include: an anti-racism assessment of the congregation; adding more nonwhite content in worship and children's programs; a demographic study of your congregation's service area to determine likely new members; etc. By breaking up a huge goal into manageable objectives, you can make steady progress towards your goal.

Objectives can range from very narrow and specific, to quite broad; but objectives should always be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound — the acronym SMART can help you remember these criteria. Goals, as opposed to objectives, can be vague, difficult to measure, and aspirational rather than attainable — though even goals should be relevant and time-bound.

Sometimes you come to the realization that a goal you've been working towards is no longer attainable, or must be modified. For example, you may start a capital campaign in order to build a new building, only to have a sharp economic recession set in just as you begin soliciting donations. In this example, trying to reach your initial fund-raising goal may now be unrealistic. So it's wise to be willing to change course when necessary, in this case by lowering your expectations. There can also be times when you should raise expectations — I remember one capital campaign that reached its fundraising goal in a month, far more quickly than expected, and the leaders of the campaign realized, too late, that they should have adjusted their fundraising goal upwards.

The world around us is constantly changing, and those changes can have big effects on congregations. A perfect example of this: after the Second World War, demographic changes in the United States meant there were many more children, and at the same time, many more people were seeking out religious communities to belong to. As a result, it was relatively easy to increase the size of congregations. In another example, the pandemic which began in 2020 has driven a demand for more online programs and ministries, but it also drove away people who only wanted in-person programs and ministries. These examples show that changes in the world outside of congregations can have a huge influence on what goes on inside congregations.

One of the key skills in change management is responding to outward changes promptly. This is above all a matter of being flexible. Congregations that cling to rigid ways of doing things are not flexible, and may find that navigating changes imposed from the outside to be incredibly painful. In an obvious example, many Unitarian Universalist congregations are predominantly white, yet U.S. society is rapidly becoming majority non-white. Those congregations that rigidly cling to their white identity (even if they do so unconsciously) are going to find the next decade or so to be incredibly painful, with declining membership, declining revenue, and declining relevancy; flexibility, on the other hand, reduces the pain of inevitable change.

Thus, our own internally-driven goals — membership growth, increased giving, etc. — must take into account the realities of how the world is changing around us. If we have a goal of increasing membership in the 2020s, we have to consider that the religion “market” is shrinking, and that we're entering a world with a non-white majority. If we fail to consider such changes in the world outside our congregation, we will be doomed to frustration and even failure.

When you reach your objectives, celebrate success — then set a new objective and move on. If you fail to meet your objectives, analyze what went wrong — did the world change around you? was your objective unrealistic? did some stakeholders balk? — then set a new objective and move on. Change management is always an ongoing process of analyzing data, setting goals, working towards those goals and measuring progress (or lack thereof), and then starting the process all over again. Change is the only constant, so we must always keep changing as the world around us changes. To quote the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus:

“Into the same river you can not step twice, for other and still other waters are flowing.” (trans. by G.T.W. Patrick)

So far, I've emphasized metrics, goals, and other technical approaches to change managment. I'll conclude with some thoughts on how to engage in humane change management — change management that emphasizes human wants and needs and aspirations.

Unitarian Universalist congregations exist to serve people. Congregations also exist to serve a larger purpose, and at least one result of that larger purpose will be to make people's lives better. I know that sounds obvious, but it needs to be said.

Therefore, when managing change, you'll want to put people first. Problems arise, of course, when serving one group of people better means you can't serve another group of people — as, for example, when you increase one budget line item at the expense of other line items. In fact, change management often necessitates making choices about which people can be served best, and which people can no longer be served. Such choices can lead to conflict. So while we always want to put people first, we also have to acknowledge the inevitability of conflict. But even in the face of inevitable conflict, our common humanity calls on us to put people first: to listen to everyone's concerns as we manage change together; to hear the pain if some of us lose something we had hoped to keep; to treat each other considerately and humanely. We should be especially aware that some people have less power than others, and we should be especially careful to treat those who are less powerful considerately and humanely.

Congregations often feel like big extended families. Edwin Friedman, who was both a rabbi and a psychotherapist, noticed this, and discovered that a branch of psychology called family systems theory could provide useful insights into how congregations function. His book Generation to Generation: Family Process in Church and Synagogue (New York: Guilford Press, 1985), though written decades ago, remains incredibly useful today for those who want to learn how to manage congregational change in a humane way.

To oversimplify a bit, Friedman's book tells us that congregations have generations in much the same way that biological families do; and that the habits formed by an older congregational generation get transmitted to succeeding generations without conscious thought. Sometimes these habits are healthy and productive, but they can also be unhealthy and destructive.

Speaking from my own experience, I have found this generational model to be a useful and practical model for understanding congregational dysfunction. In one example from my own experience, when congregational lay leaders exhibited a seemingly inexplicable distrust of me as their minister (inexplicable because I had been in the congregation for too short a time to have earned that distrust), it turned out that this habit of mistrusting ministers had been inherited from a previous generation of lay leaders. That earlier generation of lay leaders had had good reason to distrust an earlier minister, as he had sexually molested teenagers in their congregation. Their habit of distrusting ministers was a good habit to have when they had a molester as minister; unfortunately, once he was gone, this habit meant they were unable to work effectively with me or any other minister.

While the story I just told may seem extreme, stories like this are actually fairly common. The habits formed by one generation, and passed to the next generations, can have a variety of causes: past clergy misconduct; embezzlement by past lay leaders; or any violation of trust by leaders. Other forms of trauma can also cause leaders to form unproductive habits: one congregation had had to tear down their beautiful church building because they were unable to maintain it, and thirty years later the leadership habits that arose from that traumatic event still haunted them.

If you are confronted with seemingly unexplainable behavior in your congregation — patterns of behavior that don't seem to match the current reality — you might start searching for traumatic events in the past that led to those patterns of behavior. Your search may be difficult, because the traumatic event may have been kept a dark secret. But if you're able to listen to congregational elders openly and nonjudgementally, the stories may come out. If you do uncover a past traumatic event, and if you try to talk about it openly, you can expect a wide range of reactions including denial, hostility, anger, etc. So please take care of yourself. Find others who recognize the problem that you can work with. It's also good to find a professional from outside the congregation, someone who is experienced in helping organizations change unhealthy patterns of behavior; such professionals may include interim ministers, denominational field staff, outside consultants, etc. In short, don't do this alone. (Personally, I've also found it helpful to talk regularly with a psychotherapist who is trained in family systems, e.g. a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist [LMFT], and who is also comfortable with organized religion.)

Mind you, you shouldn't expect to change established patterns of behavior overnight. In the case of the congregation where a past minister had molested teenagers, it took them decades of work to finally develop a productive relationship with their minister. In the case of the congregation that had to tear down their beautiful old building, again it took decades to establish new and more productive patterns of behavior. Patience is required. And when you become impatient, it's worth remembering that even when there are past traumas and unproductive patterns of behavior, congregations are still able to provide crucial ministries and programs that help people and even save lives. To put it another way, one unproductive pattern of behavior does not mean that the entire congregation is worthless; that kind of binary thinking is in fact unhealthy.

One last thought: We know quite a bit about how clergy misconduct can lead to congregational trauma; we learned this from the feminist movement that changed Unitarian Universalism beginning in the 1970s. We know much less about how racism and racial misconduct can lead to congregational trauma; the anti-racism movement within Unitarian Universalism has been far less effective than the feminist movement. As the antiracism movement within Unitarian Universalism grows stronger and more skilled, I expect we'll find unproductive patterns of behavior in our congregations which can be traced back to trauma arising from racial misconduct. This is an emerging trend that we should all pay attention to.

Change and grief go together. Change means that something that once existed has been changed, replaced by something new. Even when change is good, there will be those who mourn that which is lost. This, by the way, is why people cry at weddings. A marriage generally represents a good change in the lives of the two people who are getting married. But the parents of those who are getting married, while glad that a new family is forming, are also sad that their child is further separating from them.

Those who are managing change, therefore, would do well to look for signs of mourning and grief, and they should help those who are grieving to work through their grief productively. Fortunately, most congregations are really good at helping people grieve — it's one of the things we do best. We can use our skills at helping people grieve, to help manage change.

When we are hoping for change, we often want the change to come sooner rather than later. However, when a congregation is recovering from a traumatic event, the process of recovery can slow down the hoped-for change. That's because people who are recovering tend to be inefficient. And inefficiency can slow down change. A case in point is the COVID pandemic. This has been a traumatic event for everyone. Even if you made it through the pandemic is great shape, nevertheless you know lots of people who were traumatized by the pandemic, and that alone can cause low-level trauma. The pandemic caused widespread trauma, and at the same time the pandemic meant we had to change how we operated our congregations — moving programs and worship services online was a big change for most congregations. But moving programs and services online was often slow and inefficient. Rather than berating ourselves for our slowness and inefficiency, we can instead realize that we were slowed down by trauma. We did the best we could, and there's no purpose in berating ourselves.

Examples of other traumatic events that can affect congregations include: a minister who betrays trust by molesting teenagers; a lay leader who embezzles large amounts of money from the congregation; having a building burn down; etc. After events like these, you can expect people to be feeling some level of trauma.

When a congregation is recovering from trauma, it is wise for leaders to be gentle. Adopt a gentle approach to change management. Healing from trauma should be the first priority. Change management can actually be part of the healing process, if handled well. In many cases, healing from trauma involves some kind of grieving, and as we know, congregations are quite skilled at helping people through grief. Sometimes change needs to happen before there is healing from trauma — for example, congregations had to make big changes in the middle of the COVID pandemic, long before there was time to heal — but if the change is handled gently, and if everyone knows there will be time for healing later on, then the change will proceed more smoothly.

In closing, let me reiterate that change management in congregations should always put people first. Because of this, I've come to believe that change management cannot be learned out of books, or from webpages like this one. You can learn about change management from books and webpages, but you learn how to do change management in community with other people.

I hope this webpage will help you to embrace change, manage it humanely, and move confidently forward into the ever-changing future.