Today is the two hundredth anniversary of Theodore Parker’s birth. I’ll leave it to others to talk about his contributions to Transcendentalism; his scholarship, and the way he brought the insights of German philosophy and theology to New England; how he drew some two thousand people to his sermons at his church in Boston. Others can tell you about his intellectual and professional accomplishments; I’d rather think about his home life. Here, then, is a sketch of Theodore Parker’s Boston house, from Theodore Parker: a biography, Octavius Brooks Frothingham (1880, pp. 241-242, 244):

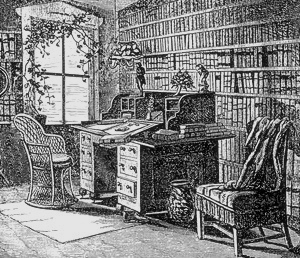

“In January, 1847, Mr. Parker removed from West Roxbury, where he had been living till now, to Boston. A house in Exeter Place — a little court, so near to Essex Street that his yard was adjacent to that of his friend Wendell Phillips — was provided for him. The upper floor was thrown into one room for a library. In this house he lived till his last sickness took him away: there his widow resides still, though the quiet of the spot is invaded by business. The household consisted of himself and his wife, whose domestic name is Bear, or Bearsie, and who, as usual, is nearly the opposite of her husband, except in the matter of philanthropy; a young man by the name of Cabot, one and twenty years old, an orphan, brought up by Mr. and Mrs. Parker from childhood, and treated by them as a sort of nephew; and Miss Stevenson, “a woman of fine talents and culture, interested in all the literatures and humanities.” The entire house was given to hospitality. The table always looked as if it expected guests. The parlors had the air of talking-places, well arranged and habitually used for the purpose. The spare bed was always ready for an occupant, and often had a friendless wanderer from a foreign shore. The library was a confessional as well as a study: this room, airy, light, and pleasant, was lined with books in plain cases, unprotected by obtrusive glass. Books occupied capacious stands in the centre of the apartment; books were piled on the desk and floor. There was but one table, — a writing-table, with drawers and extension-leaves, of the common office pattern. A Parian head of the Christ, and a bronze statue of Spartacus, ornamented the ledge: sundry emblematical bears, in fanciful shapes of wood or metal, assisted in its decoration. The writer sat in a cane chair: a sofa close by was for visitors. A vase of flowers usually stood near the bust of Jesus. Flowers were in the southern windows, placed there by gentle hands, and faithfully tended by himself. Two ivy-plants, representative of two sisters, intwined their arms and mingled their leaves at the window-frames. Every morning he watered them, and trained their growing tendrils. … In the winters of heavy snow he kept a little corn-crib in his library, and regularly fed at the window-sill the city pigeons deprived of their street-food. They soon found where breakfast was to be had, and flocked daily to the window; while he, with delight, watched them as they cooed and quarrelled, and hustled each other, and sidewise nodded through the pane at him.”