The final installment of the Prometheus myth:

As usual, full script is below….

Continue reading “Prometheus, part 4”Yet Another Unitarian Universalist

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

The final installment of the Prometheus myth:

As usual, full script is below….

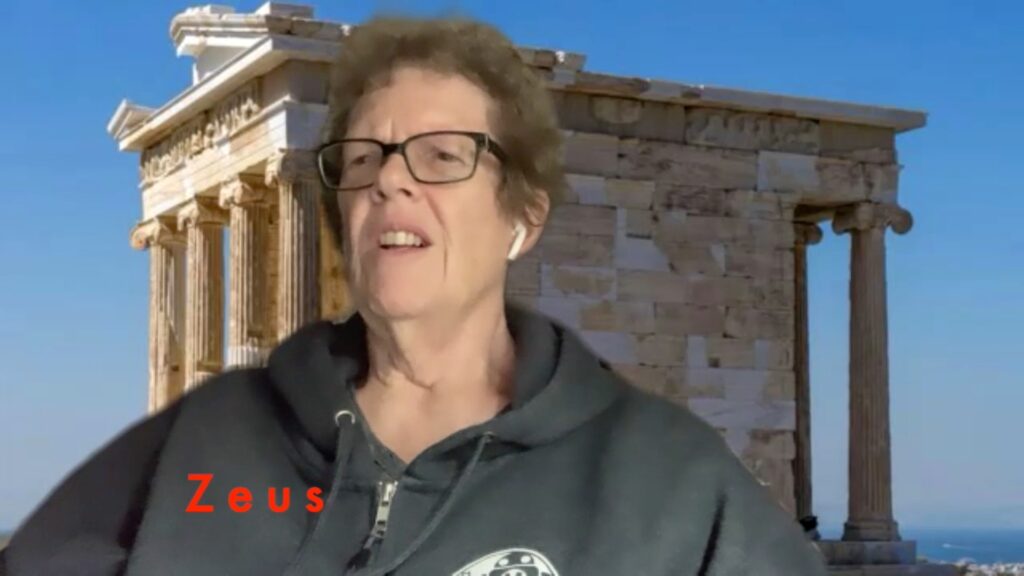

Continue reading “Prometheus, part 4”William R. Jones, UU theologian and one-time religious educator, pointed out may years ago that the myth of Prometheus serves as a useful counter to the myth of Adam and Eve. For Adam and Eve, rebellion is sinful; for Prometheus, “a response of rebellion is soteriologically authentic.” Although Jones considers the Prometheus myth to be important for humanists, I think Prometheus is important for anyone who is an existentialist — which means almost every Unitarian Universalist today, whether they are humanist existentialists, Christian existentialists, pagan existentialists, Buddhist existentialists,….

That means the myth of Prometheus should be an integral part of Unitarian Universalist religious education for kids. Here’s one attempt to make that happen, as several ordinary people go back in time to relive the myth o Prometheus:

Full script is below….

Continue reading “Prometheus, part one”(Be forewarned: this is a blog post about theology. Some of us enjoy theology, but if you don’t, this will not be fun for you.)

Mark Morrison-Reed, in his lecture “The Black Hole in the White Psyche” (online here, and in the fall, 2017 issue of UU World magazine), asserts that Unitarianism appealed to members of the African American intellectual elite through the late nineteenth and twentieth century, citing the Unitarian affiliations of people like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and Whitney Young. Universalist theology, on the other hand, did not appeal to African Americans:

“Universalism … was difficult for African Americans to embrace. A loving God who saves all is, for most African Americans, a theological non sequitur. Why? In an article entitled ‘In the Shadow of Charleston,’ Reggie Williams writes about a young black Christian who said, during a prayer group following the murder of nine people at Emanuel AME Church in 2015, ‘that if he were to also acknowledge the historical impact of race on his potential to live a safe and productive life in America, he would be forced to wrestle with the veracity of the existence of a just and loving God who has made him black in America.’ This is the question of theodicy: How do we reconcile God’s goodness with the existence of evil? In the context of Charleston, the context of Jim Crow, the context of slavery, what is the meaning of black suffering? Why has such calamity been directed at African Americans? If God is just and loving there must be a reason. If there is no reason, one is led to the conclusion that God is neither just nor loving.”

What Mark says is clearly true. Yet there were a tiny handful of African American Universalists during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. What drew them to Universalism? Continue reading “Saving Universalist theology”

Hassahan Batts writes: “Practitioners Research and Scholarship Institute (www.prasi.org) is having another writing retreat where we are bringing together students of Dr. Jones in Allentown, Pennsylvania. If interested please email justequality@yahoo.com .”

No date given, so if you’re interested I’d suggest writing to the above email address right away.

The text of the formal presentation portion of my workshop:

Let me begin by telling you about the context in which I do religious education. I’m minister of religious education at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, California, a mainline congregation founded in 1947. Like so many mainline congregations founded in the post-World War II era, today we struggle to adapt to new and different demographic, economic, and theological realities. In particular, we’re trying to figure out what the end of Christendom means to us as a post-Christian congregation, and we’re adapting to an intensely competitive nonprofit landscape.

Four years ago, I suggested to our lay leaders that we might do a six-week spring curriculum unit in peacemaking for K-5 Sunday school classes. That program, which I based on an old 1980s curriculum called “Peace Experiments,” was described by Geez magazine — a magazine subtitle “Holy mischief in an age of fast faith” — like this:

In this comment, Hasshan Batts writes:

“Practitioners Research and Scholarship Institute (PRASI) www.prasi.org is gathering a collective of individuals that have been influenced by Dr. Jones’ oppression theory for an upcoming writing project. If interested please email me at justequality@yahoo.com”

When I was in college, I wanted to take a course that was being offered on the history of jazz; but I was still a physics major, and didn’t have the time. So I bought the main book for the course, Blues People by LeRoi Jones, and read it on my own. I was listening to a lot of jazz at the time, and Jones — who had changed his name to Amiri Baraka by the time I read the book — showed me how jazz grew out of the historical and social experiences of people of African descent in the United States. It was one of those books that changed the way I understood the world, and started me off on an intellectual journey that led to Harry T. Burleigh and James Weldon Johnson and Sun Ra, and (by a circuitous route) to James Cone and William R. Jones.

Blues People has, I think now, a deep theological strain to it. When I read James Cone’s The Spirituals and the Blues, I couldn’t help comparing Cone’s understanding of African American music to Baraka’s understanding, not entirely favorably. Cone focuses too much on Christian doctrine, and I think that tends to exclude some of the irreducible African-ness of the spirituals and the blues, and later jazz. Baraka, on the other hand, showed how African Americans remained a part of the African diaspora, keeping their spirituals in some sense separate from the white man’s religion, and he showed (I thought so, anyway) the way so-called secular music could made sense out of lived experience, could bring meaning to life. I later learned — heard, really — how jazz could incorporate the lived experiences and meaning-making of other cultures, particularly Latin American cultures, but also various white North American cultures. Baraka opened my eyes to how jazz can express cross-cultural thoughts and longings and meaning-making, and so I came to understand it as the religious music par excellence. And so it was that Baraka opened my heart to William R. Jones’s Is God a White Racist? (the answer to the title is a nuanced and qualified yes). I don’t think you can understand God in the same way after you’ve read Blues People.

Baraka’s poetry had less of an impact on me. I love some of his individual poems: “Numbers, Letters,” for example, had some exquisite lines that have stayed with me for years, that match or surpass anything written by Allen Ginsberg or the more famous white Beats:

If you’re not home, where

are you? Where’d you go? What

were you doing when gone? When

you come back, better make it good….

…I am Everett LeRoi Jones, 30 yrs. old.

A black nigger in the universe. A long breath singer,

wouldbe dancer, strong from years of fantasy

and study….

That’s what I wanted to be: a long breath singer who is strong from years of fantasy and study; but I never made it, though the poem stayed with me. Some of Baraka’s poems have been living inside me for years: “Numbers, Letters” of course; and “For Hettie” and “Legacy” and “Poem for Speculative Hipsters” and others. But I could never sit down and read a whole book of his poems, the way I could with Langston Hughes or Elizabeth Bishop (I must have read “Geography III” a few dozen times) or Denise Levertov or Lucille Clifton. The fault is mine, I know. I can recognize Baraka’s brilliance, I can appreciate the bracing clarity of his moral insight, I need the white heat of his anger — but I feel that he demands something of his readers (and of himself) that is beyond human ability; or at least beyond my ability. It’s hard to read a whole book of poetry when you know that you’re going to fall short of what the poet demands of you; when you know that you or any error-prone, love-befuddled, smelly, awkward, confused and all-too-human being can not live up to what the poet demands. Adrienne Rich is a little that way, too: when I read poets like Baraka and Rich, I know I’ll never be good enough, never be able to transcend my humanness, never be able to get to that land towards which they point. It’s tough to read a whole book that makes you feel that way.

And it’s hard to know what we’ll do without Amiri Baraka. We need people who will hold us to impossible standards. I miss him already.

On Thursday, January 31, Amy, the senior minister at our church, and I are going give a class on theological unity within Unitarian Universalism. We’re starting our class with an online conversation about the topic. And I’m going to begin my side of the conversation by listing five areas where I think Unitarian Universalists already have some degree of theological unity:

(1) Women and girls are as good as men and boys: During the 1970s and 1980s, Unitarian Universalism, like many liberal religious groups in the U.S., went through the feminist revolution in theology. We came out of those decades with a very clear theological consensus: when it comes to religion, women and girls are just as good as men and boys.

(2) Human beings must take responsibility for the state of the world: The Unitarian Universalist theologian William R. Jones has argued that humanists and liberal theists have come to resemble each other in that both affirm the radical freedom and autonomy of human beings (“Theism and Religious Humanism: The Chasm Narrows,” Christian Century, May 21, 1975, pp. 520-525). Today, we have a wide consensus that, whether or not we believe in God, none of us believes some larger power is going to come fix up our problems for us — if humans made the mess, it’s up to us to fix it.

I discovered an article on William R. Jones from a 1975 Grinnell College newspaper. The views attributed to Jones in the article correspond closely to some of his writings from the early 1970s, including the book Is God a White Racist? and the essay “Humanism and Theism: The Chasm Narrows.” But the article is still worth reading for two quotations, both of which sound like they accurately report Jones’s thoughts: “Humanism does not require the death of God. All it requires is the affirmation of human freedom” and “The humanist does not regard the Christian God as ultimate reality, but he does not disregard ultimate reality.” I wish some scholar would go through Jones’s papers to see if the texts of the two lectures reported in the article are still extant; I find the first quotation particularly interesting, and would like to be sure of its accuracy.

The text of the article follows: Continue reading “William R. Jones in 1975”

While on vacation, I missed the death of Rev. Dr. William R. Jones, who died on July 17 at age 78; commenter Dan Gerson drew my attention to that fact today. Jones was the pre-eminent Unitarian Universalist humanist theologian of the past fifty years, one of the handful of truly important Unitarian Universalist theologians of any kind from the past half century, and arguably the best Unitarian Universalist thinker on anti-racism.

Jones is a major figure who deserves a full critical biography, which I am not competent to write. But here is an all-too-brief overview of his life and work:

Education and ministry

William Ronald Jones was born in 1933. He received his undergraduate degree in philosophy at Howard University. He earned his Master of Divinity at Harvard University in 1958, and was ordained and fellowshipped as a Unitarian Universalist minister in that year. He served from 1958-1960 at a Unitarian Universalist congregation in Providence, Rhode Island. Mark Morrison-Reed states that Jones served at First Unitarian as assistant minister (Black Pioneers in a White Denomination, p. 139), but the UUA Web site states that he served at Church of the Mediator as “minister”; I’m inclined to believe Mark’s book, as the UUA listings of ministers are prone to error.

After a two-year stint as a minister, Jones went on to do doctoral work in religious studies at Brown University, receiving his Ph.D. in 1969. His dissertation was titled “On Sartre’s Critical Methodology,” which discussed “Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophical anthropology” (Lewis R. Gordon, An Introduction to Africana Philosophy [Cambridge University, 2008], p. 171).

As you can see, Jones quickly moved from the parish to the academy. Of course he was well suited to the academy because of his intellectual abilities, but also there is little doubt that there were few doors open for African American ministers looking for Unitarian Universalist pulpits in the 1960s.

The years at Yale

After receiving his Ph.D., Jones was an assistant professor at Yale Divinity School from 1969 to 1977. It was while he was at Yale that he gained renown as a Black theologian with a unique take on the issue of theodicy. Continue reading “William R. Jones: a brief appreciation”