I finally finished writing a short essay titled “Reimagining Sunday school” for my curriculum website. This essay has been in the works for a while, both as a response to the “death of Sunday school” movement, and as a response to the de-funding of religious education programs that we’ve been seeing denomination-wide. I’m copying the entire essay in below the fold, or you can read it on my curriculum website.

Continue reading “Reimagining Sunday school”Tag: Sunday school

The evolving state of religious education

I am increasingly convinced that the pandemic is accelerating a number of trends that are going to change the way we do religious education in our local congregations fairly quickly. However, I don’t these trends should lead us to proclaim either the “post Sunday school era” or “the death os Sunday school.”

And before you get too excited (“Yay, the death of Sunday school!”) or too sad (“Nooo, I miss Sunday school!”), let’s look at a couple of the trends that affect religious education, trends that are being accelerated by the pandemic…..

1. Current trends affecting religious education

2. Where we came from, 1781 to the present

1965-2005

1900-1965

1781-1900

3. Why the “post Sunday school” advocates are right

4. Why the “post Sunday school” advocates are wrong

5. Expanding our religious education possibilities

6. The whole church as curriculum

7. New models for funding

8. Final thoughts

———

1. Current trends affecting religious education

First and foremost among current trends, most American congregations face looming financial difficulties. Staff costs continue to outpace inflation, driven in part by health insurance costs. Staff costs in Unitarian Universalist congregations are also under pressure because we expect our professional staff — both ordained ministers and lay religious educators — to have at least a four year college degree, and often three or more years of graduate study; staffers have to pay off their college debts, and that means they need relatively high salaries. Finally, there’s always Baumol’s Cost Disease: American congregations represent an “technologically stagnant sector” which means congregations experience “above average cost and price increases.” The amount each person gives to a congregation has to increase faster than inflation, just so the congregation can provide the same amount of services.

Continue reading “The evolving state of religious education”Updated Sunday school teacher manual

I just completed a major re-write of A Manual for Sunday School Teachers in Unitarian Universalist Congregations.

Among other improvements, I completely rewrote Section 2, “Basics of Teaching and Learning,” based on my observations of what new Sunday school teachers really want to know. On Saturday, I’ll be leading a workshop on “Teaching 101” at Pot of Gold, the district religious education conference, and I’ll base this workshop on the revised Section 2 (with added hands-on activities).

I’ll post the table of contents below the fold.

Above: A Sunday school teacher coaching a middle schooler on how to use a power tool during a Sunday school class at my church. No, this is not your mother’s Sunday school!

What’s killing Sunday school

A follow up to this post.

If Sunday school is going to die, what’s going to kill it? Let’s look at four social and economic factors that are leading to declines in U.S. Unitarian Universalist Sunday schools — and when I talk about decline, I’m talking about decline in enrollment, decline in attendance (which differs from enrollment), decline in interest among children and teens, and decline in interest among adults.

(1) The biggest single demographic factor affecting Sunday school enrollment has to be increasing diversity in the U.S. population. The majority of Unitarian Universalist congregations remain racially and ethnically segregated. That segregation may result from one or more of several causes: (a) Many Unitarian Universalist congregations are located in racially homogenous municipalities, typically upper middle class white towns that have the political power to keep people of color out. (b) Power structures in many Unitarian Universalist congregations are dominated by older white people who remain uncomfortable with the increasing racial diversity of the world around them, and enforce the whiteness of their congregations through a variety of means, including so-called microaggressions, blindness towards their congregation’s biases, talk about how “those people” wouldn’t want to be Unitarian Universalists because they’re all Catholics, or all Buddhists, or what have you; and still other means beyond these. (c) The way Unitarian Universalist congregations tend to imagine diversity primarily in terms of a white congregation adding a few black members, thus ignoring the stunning racial, linguistic, and ethnic diversity of much of the country, including the incredible diversity of people who are lumped together as “Hispanic” and “Asian,” and also including the way that some racial or ethnic groups get obscured by overly broad categorizations (such as Lusophones who are lumped in with Hispanics, or the treatment of “blacks” as a monolithic ethnic group).

For many people, our workplaces, schools, and community groups all have some racial and ethnic diversity. Thus, a parent who walks into a Unitarian Universalist congregation that is overwhelmingly white — and this includes a white parent — is going to feel that this is a strange place, and maybe a place they don’t want their children to be part of.

How can we address this demographic factor? Continue reading “What’s killing Sunday school”

Is Sunday school dead?

Many liberal religious educators these days are talking about “the death of Sunday school.”

Robert W. Lynn and Elliott Wright concluded their 1971 history of American Protestant Sunday school, The Big Little School: Sunday Child of American Protestantism with the observation that people have repeatedly predicted the end of Sunday school. And 1971, the year they published their book, was a low point in the history of Sunday school: the Baby Boom was over, people were rebelling against organized religion, and Sunday schools were failing left and right. But during the 1970s, a new way of doing Sunday school emerged, exemplified in Unitarian Universalist congregations by the Haunting House curriculum, which began development c. 1971, with its activity centers, its songs and stories and creative movement, its frank discussion of birth and human sexuality, and its organizing metaphor of being at home as a religious search.

Another low point for Sunday school was 1934. The immense economic dislocations of the great Depression kept many people from being able to participate regularly in local congregations; there were in addition social trends that led to a decline in interest in organized religion. The old ways of doing Sunday school — the opening exercises, the single sex classes, the reliance on verbal instruction — no longer worked very well. In the year of 1934, Angus MacLean wrote something that could have come from today’s debates about the death of Sunday school:

“One or two of our most widely known religious educators have recently suggested that perhaps the church school should be abolished, because of its ineffectiveness. The ineffective church school should be abolished, but it would be foolish to give up the attempt to educate for the good life, until what is known of child nature and human need is taken more seriously. In any case, the most effective way to abolish anything that is worthless is to change it so that it becomes useful. Most church schools are in need of such change. What first steps can religious educators take towards transforming the church school?” — Angus MacLean, The New Era in Religious Education: A Manual for Church School Teachers (Boston: Beacon Press, 1934), pp. 31-32.

MacLean’s answer to transformation was to use the playbook of progressive education (one of the books on progressive religious education that he cites is Exploring Religion with Eight Year Olds by Sophia Lyon Fahs). The chapter titles of his book give an overview of what he thought most important in religious education: Studying Personal Relations, Measuring Society, Re-Living History, Finding Great Companions, Sharing in Imaginative Experiences, Exploring Nature, Growing in Faith. And eventually, many Universalist and Unitarian congregations followed his lead, and found great success in so doing.

But all this brings me back to the beginnings of Sunday school. Do you know what the original purpose of American Sunday school was? — it was developed to provide literacy training for children who had to work in factories. It took place on Sunday because that was the only day when child factory workers could go to school. Because Sunday school took place on Sunday, and because it was sponsored by churches, there was a good deal of religious instruction included; and a primary purpose of literacy for American Protestants was so that everyone could read the Bible. But within a generation, Sunday school had changed into something quite different from literacy training.

Is today’s Sunday school dead? I think there’s a good chance that Unitarian Universalist Sunday school is dying. Here are my reasons for saying this: 1. There are too many parish ministers who do not see themselves as having to bother with children. 2. Congregational costs are rising faster than congregations income (due, e.g., to health insurance increases), and you can easily cut costs in the short term, without big reductions in income, by reducing programs for children and teens, programs which tend to require a lot of staff time and a lot of building maintenance. 3. Sunday schools require a lot of volunteer hours, and many Unitarian Universalist congregations are not particularly adept at volunteer management; as a result, it’s increasingly difficult for many congregations to find adequate volunteers. 4. I’m not seeing much in the way of new, theologically rich, intellectually stimulating, and spiritually deep curriculum resources.

5. Finally, there seems to be an infatuation among Unitarian Universalist thought leaders for what they call “faith formation.” My understanding of faith formation is that it comes from liberal Christian world religious educators who find great inspiration in the Biblical book of Isaiah, where it says: “Yet you, Lord, are our Father. We are the clay, you are the potter; we are all the work of your hand.” (64.8) So the dominant image for faith formation is of children as unformed clay, who need to be formed in their religious faith. Sunday school is indeed ill-suited to faith formation imagined in this way; if you want to mold children into a certain kind of vessel, there are better ways of doing it than the usual chaos of the Unitarian Universalist Sunday school.

So yes, Unitarian Universalist Sunday school is probably dying — if it’s not already dead.

But I don’t think Sunday school needs to die. Since the first Sunday schools devoted to literacy in the late eighteenth century, the phenomenon of Sunday school has repeatedly changed to meet the needs of different times.

And I don’t think Sunday school should die. I don’t like the image of children being molded like clay. I’m too much of an existentialist to be able to believe in a Christian God who molds passive humans the way he wants, nor do I believe in unbridled behaviorism as an educational philosophy. Instead, I prefer images that are more in line with what I do in Sunday school: the image of a pilgrimage, where adults and young people are traveling together towards some goal they have in common; the image of a community or collective, where we each are transformed while transforming others; the image of a support network, where we support each other as we make meaning in an absurd world.

I am too much of a progressive and an existentialist to wish for the death of Sunday school — I don’t wish for the death of collectives, or the death of of pilgrimages, or the death of shared existentialist meaning-making.

Basic classroom management for Sunday schools

At today’s “Pot of Gold” religious education conference, I led a session called “Teaching 101” in which I went over some of the basics of teaching for Sunday school teachers. Below is my handout on classroom management — a PDF version, and a text version (the PDF version has some additional material):

PDF version of “Classroom Management: Some Ideas to Help You Mange

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT: SOME IDEAS TO HELP YOU MANAGE (text only)

The basics

These are the simplest things to do to help minimize behavior problems:

(1) Make sure each child or teen is noticed and is heard. This is one purpose of the opening check-in: everyone says their name, and tells a little bit about themselves. Especially when new to a class, a young person needs to feel that they are noticed, that their voice can be heard, and that they belong. This can reduce acting-out behaviors.

(2) Help children or teens learn names of everyone in class. This is a long-term goal; at the beginning they should at least hear the names of everyone in the class during check-in. Everyone will feel more secure, and be better behaved, when they know at least barest minimum—the names—of all the adults and children/teens in the class.

(3) Be clear about the purpose of the class. It can help if everyone is reminded why they are in the class. If there’s a stated purpose, most children/teens will buy into it. When you must reprimand someone, it can help to remind them of the purpose of the class so they understand why they are being reprimanded.

(4) Be clear about the values of the class. In a UU Sunday school, we value behavior that shows we care for one another. Regular opening words (“We light this chalice…”) or a quick statement of purpose (“Here we are again to learn about human sexuality”) help remind everyone of these basic values.

More practices towards a well-managed classroom

(A) When preparing for the class, run a video in your head of how it will go. As you go over each activity, you imagine how each child or teen will respond to that activity. If an activity is very active and you know that T—— does not like to be very active, how will you involve that child/teen? If an activity requires sitting still and B—— has ADHD, how will keep that child/teen involved in the activity? Using this technique of running a video in your head as you prepare helps you build a mental model of the individuals, and of the class as a whole.

(B) Keep the educational goals and objectives in mind. Class sessions rarely go exactly as planned (one reason why teaching is so challenging and interesting). And kids often melt down when they sense that you, the teacher, have lost your direction. But if you keep in mind the educational goals (the big picture stuff) and the educational objectives (measurable things you want to accomplish in this class), you will find it easier to respond to classroom challenges. Thus when a class doesn’t respond well to a given activity, you can adapt it to their needs while still meeting your educational goals and objectives.

(C) Go from pre-assessment to teaching to assessment. “Pre-assessment” means finding out what the children or teens know before you begin teaching; in RE this probably won’t be a written test; it might be asking the children/teens what they know about topic X. “Assessment” means finding out what the children or teens have learned in the class session; again, in RE this probably won’t be a written test; it might take the form of asking the children/teens to state one thing they have learned during the closing circle. Pre-assessment and assessment can also take place just before or after a given activity.

Why does this help with classroom management? If you’re teaching a lesson about something the kids already know well, you’re likely to face behavior problems—some simple pre-assessment would let you know how to tweak your lesson plan to meet the needs of the students. Conversely, if your lesson is way above the level of the kids, you’re going to lose them, which can lead to unpleasant behaviors; again, some pre-assessment would help you to tweak the lesson so you don’t lose the kids. And some very simple assessment at the end of the class — asking each young person to say one thing they learned today, or one thing they’re taking away from the class — can help the participants see that the class had purpose and a positive outcome.

(D) Use class rituals. Children and teens will be more relaxed and comfortable when there are consistent class rituals that are followed. A suggested minimum for classroom ritual: 1. An opening ritual with names, check-in, and a restatement of the class purpose. 2. A closing circle where you review with the children/teens what they have learned.

Tracking pit

In the middle school Ecojustice class this morning, one of the things we did was to make a tracking pit. Lorraine brought some mud that got dug up from her yard (if you want to be technical, it’s a clay-like soil composed of Quaternary alluvial deposits). Some of us worked on moistening the mud till it got to the right consistency, then spreading it out on a flat spot under some bushes:

We put a bait cup in the middle of the mud, then crumbled a granola bar into the bait cup. By this evening, the bait was gone, and there were plenty of squirrel tracks in the mud:

The tracks were not as distinct as I would have liked. The mud was a little too wet, and the suqirrels slipped and slid just enough to blur the finer details of their tracks. Nevertheless, these are some pretty good tracks!

Star Island RE handouts

Below are the handouts from the workshop on teaching I led at this summer’s Star Island religious education conference. (Yes, it took me almost two months to proofread these handouts and finally post them — this gives you an indication of how very busy this year’s church start-up has been.) These handouts are aimed at more experienced Sunday school teachers, religious education committee members, and religious education professionals.

Developmental stage theory handout

Educational philosophies handout

20 years

Twenty years ago this month, I began working as a Director of Religious Education (DRE) in a Unitarian Universalist congregation. During the recession of the early 1990s, I had been working for a carpenter/cabinet-maker, so I had been supplementing my income with part-time work as a security guard at a lumber yard. Carol, my partner, saw an advertisement for a Director of Religious Education at a nearby Unitarian Universalist church. “You could do that,” she said. So I applied for the job, and since I was the only applicant, I got it.

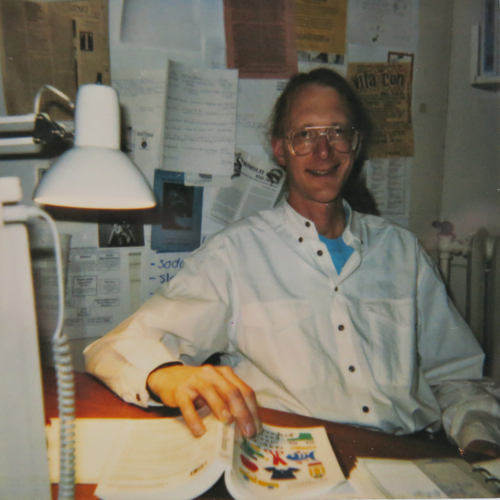

Above: Carol took this Polaroid photo of me sitting at my desk at my first DRE job. The computer in the left foreground is a Mac SE, and I have a lot more hair. It was a long time ago.

Over the past twenty years, I worked as a religious educator for sixteen years — full-time for six of those years, part-time for nine years — and as a full-time parish minister for four years. Since I was parish minister in a small congregation where I had often had to help out the very part-time DRE, I feel as though I’ve worked at least part-time in religious education for twenty continuous years.

Sometimes I wonder why I’ve stuck with it so long. Religious education is a low-status line of work. Educators who work with children are accorded lower status in our society, because working with children is “women’s work,” and ours is still a sexist society. And religious educators are sometimes looked down upon by schoolteachers and other educators, because we’re not “real” educators. In addition to being low-status work, religious educators get low pay, and the decline of organized religion means our pay is declining, too, mostly because our hours are being cut, or paid positions are being completely eliminated.

Progressive religious education in 1912

During an email exchange with a colleague regarding the history of early twentieth century Unitarian religious education, I came across a 1912 report from the Unitarian Sunday School Society.

This brief report gives an interesting look into the beginning of the Progressive era of religious education. Based on the insights of the new science of psychology, the Progressives were implementing closely graded classes, an improvement over older ungraded, or three-grade, classes. The Progressives felt that key outcomes of religious education included providing children with religious knowledge inculcating children with the ideals of social service, and teaching “religion itself.” And, although still focused on the Bible, the Unitarian Progressives were introducing non-Biblical and non-Christian topics to Unitarian children.

For me, the most interesting part of this essay is the penultimate paragraph. With some rewriting, this Progressive statement could serve as a pretty good summary of what we’re still trying to do in our Sunday schools today — something like this:

“We should teach our children about religion — they should know religious history, literature, and theology.

“We should teach our children how to apply religion — they should know that as a tree bears fruit, so religion should produce good works.

“Finally, we should teach our children religion itself. Knowledge about religion points towards religion itself; and religious service grows out of the high ideals of religion itself. But when we teach religion itself — as opposed to knowledge about it, or service based on it — we won’t teach it through classroom instruction. Like all our best knowledge, religion is transmitted by contagion and inspiration, not by instruction; it is caught, not taught. To reach and quicken the child’s religious nature is the highest task of religious education.”

The full text of the essay appears below.