Nights get cool in the dry desert air of Elko, and we left the window of the motel room open all night. We got on the road while the air was still cool. We were about to turn on the audiobook we have been listening to — Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in the translation by Burton Raffles — when I saw a sign by the side of the road: “California Trail Interpretive Center.”

“Do you mind if we stop there?” I said to Carol. She knew that I have become mildly obsessed with the California Trail on this trip, so she agreed we could stop.

We climbed up the short trail behind the Interpretive Center building, and looked down on the Humboldt River valley: the narrow river winding along the low point of the broad valley; bright green grass and even a few trees growing near the river; the green grass giving way to sagebrush as the land sloped up away from the river; and then, rising more and more steeply above the level of the sagebrush, the stark and almost bare slopes of towering mountains.

Above: The Humboldt River valley east of Elko, Nev.

Edwin Bryant, in his 1848 book What I Saw in California, described how his party made the difficult crossing of the salt flats west of Great Salt Lake, and then made their way across the often steep and difficult terrain of what is now western Nevada, finding barely enough water, and barely enough grass for their mules, at widely spaced springs. After more than a week of travel through this harsh desert, Bryant and his party found a small tributary stream which finally led them to the Humboldt River (which they called Mary’s River):

“We emerged into the spacious valley of Mary’s River, the sight of which gladdened our eyes about three o’clock, P.M. At this point the valley is some twenty or thirty miles in breadth, and the lines of willows indicating the existence of streams of running water are so numerous and diverse, that we found it difficult to determine which was the main river and its exact course…. At sunset we encamped in the valley of the stream down which we had descended, in a bottom covered with the most luxuriant and nutritious grass. Our mules fared most sumptuously both for food and water.”

Today, the Humboldt River valley looks somewhat different than it did in Bryant’s day: the river has been restricted to one main channel; most of the trees are gone and the river bottoms are used by farmers to grow feed for cattle; cattle graze on sagebrush above the river bottom; and the interstate highway and a railroad run between the agricultural land and the grazing land. But even in this time of interstate highways and air conditioned automobiles, I still found the green of the valley to be a welcome sight in the midst of a land that appeared to me to be dry and forbidding landscape.

My perception of this land as dry and forbidding is not shared by the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshones. On their tribal Web site, they write: “This vast land of mountains, valleys, deserts, rivers, and lakes offered an abundance of wildlife and plants for the Shoshone to hunt, fish, and gather. The Newe [the name by which they call themselves] knew their lands and cared for its natural balance; for them it was a land of plenty.” And, Steven J. Crum, in his book The Road on Which We Came: A History of the Western Shoshone (Salt Lake City University of Utah Press, 1994), quotes a Western Shoshone song:

“How beautiful is our land,

how beautiful is our land,

forever, beside the water, the water,

how beautiful is our land.

“How beautiful is our land,

how beautiful is our land,

Earth, with flowers on it, next to the water,

how beautiful is our land.”

We kept driving west, generally following the course of the Humboldt River, for the next two or three horus. Bryant and his party followed the Humboldt River for more than a week, from August 9 through August 19, when at last they reached the Humboldt Sink — that place where the river terminates:

“We came to some pools of standing water, as described by the Indians last night, covered with a yellowish slime, and emitting a most disagreeable odor. The margins of these pools are whitened with an alkaline deposit, and green tufts of a coarse grass, and some reeds or flags, raise themselves above the snow-like soil.”

The Humboldt Sink is another weird landscape, forty-five miles of undrinkable water, halophytes or salt-loving plants, whitish soil — and forty-five miles of misery for the early travelers along the California Trail. The Western Shoshone appear to have been smart enough to stay out of the Humboldt Sink. But the white emigrants had to cross it in order to get to California. Mark Twain had to cross it in his 1861 trip by stagecoach in order to get to his final destination of Carson City:

“…forty memorable miles of bottomless sand, into which the coach wheels sunk from six inches to a foot…. It was a dreary pull and a long and thirsty one, for we had no water. From one extremity of this desert to the other, the road was white with the bones of oxen and horses. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that we could have walked the forty miles and set our feet on a bone at every step! The desert was one prodigious graveyard. And the log-chains, wagon tyres, and rotting wrecks of vehicles were almost as thick as the bones. I think we saw log-chains enough rusting there in the desert, to reach across any State in the Union. Do not these relics suggest something of an idea of the fearful suffering and privation the early emigrants to California endured?”

Above: The Humboldt Sink near Interstate 80 in Nevada

Why did those early emigrants make that trip? — traveling west for hundreds of miles into uncertainty. The emigrants may have been able to give rational explanations of their desire to emigrate; but, suggests historian George R. Stewart, there were other, non-rational, factors at work:

“We may suspect some unconscious motivation. Moving was an established folk custom. Most of these people had already moved once, or oftener, and to do so again was only natural. Moreover we may suspect that many of them were driven on by mere boredom. To exist for a few years on a backwoods farm with almost no means of amusement or stimulation meant the build-up of an overwhelming desire to see new places and people.” (The California Trail [New York: McGraw Hill, 1962].)

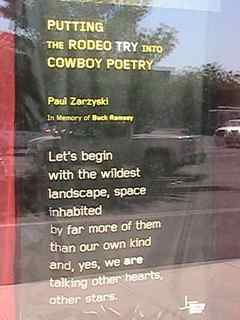

It seems a little extreme to suggest someone would travel that far into such uncertainty out of boredom; Mark Twain was driven to emigrate to Nevada out of a species of boredom, but that was later, when there was regular stagecoach service across the continent. But boredom is related to other human feelings, including religious feelings — what is meditation, but organized boredom? — and as meditation is related to boredom, so are both related to ecstasy. The early travelers along the California Trail must have endured mind-numbing boredom at some stages along the trail; but in other places they experienced the terrifying sublimity, the awe-inspiring grandeur, of the land; the awe and sublimity and terror amplified by partial starvation and fear and exhaustion, and their earlier boredom. We drove most of the day through the Nevada landscape on not enough sleep, we were sometimes bored by driving, and we were awe-struck by the sight of the mountains and canyons; terrified by the steep winding downgrades; horrified by the sight of a fire-blackened hulk of a truck that we passed in slow single-file line of vehicles as fire fighters put out the last of the brush fire that the explosive burning of the truck had started, passed in horrified realization that no one could possibly be left alive after that crash and fire, that crash that obviously came from the truck losing control on one of those steep winding downgrades that we were now negotiating. The emigrants had far more intense experiences that lasted far longer, and extended over months. Such things work changes on one’s being.

On the other side of the Humboldt Sink, the interstate roughly follows the Truckee River — again, one of the routes of the California Trail, a route that guaranteed fresh water and forage for oxen and mules. We stopped at the rest area at Donner Pass — this rest area is not far from where the ill-fated Donner party were snowbound, and where nearly half the party died — and to stretch our legs we walked a short distance along the Pacific Crest Trail.

There we met a man who was through-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. He was older than the typical through-hiker, ten or twelve years older than I, and since we were near contemporaries of his, it was easy to wind up talking with him. He told us about walking 700 miles through the desert, sometimes having to carry enough water to last him for 30 miles. When he got to the high Sierras, the altitude hit him hard, slowing him down until he became finally acclimated. Carol asked about the logistics of renewing his supplies, and he said that once he had to walk a full day, or about fifteen miles, off the trail to pick up supplies, and then walk a full day to get back on the trail.

His motivation for taking on such a physically and mentally challenging trip was simple: his son was killed in an accident, then his wife died, and he had to do something. We talked about what might motivate other through-hikers. “We’re listening to The Canterbury Tales as we drive,” I said, “and I think through-hiking is a kind of modern-day pilgrimage.” Through-hikers have no pilgrimage destination, no Canterbury with Saint Thomas’s remains at journey’s end; there is only the journey. But like the pilgrims going to Canterbury, and like the emigrants, they begin their journeys with the advent of warm weather:

“When Zephyrus eke with his swoote breath

Inspired hath in every holt and heath

The tender croppes and the younge sun

Hath in the Ram his halfe course y-run,

And smalle fowles make melody,

That sleepen all the night with open eye,

(So pricketh them nature in their corages);

Then longe folk to go on pilgrimages….”

So, too, I began to long for this cross-country trip in the early spring, looking through the road atlas to choose a route, making plans about where we would stop, dreaming about when we could start driving.

All pilgrims must complete their journeys before the harsh weather of winter sets in. Our through-hiker worried that he might be walking too slowly, he might not make it through the mountains of Washington before the winter snows set in. I said I wasn’t sure that mattered, and he allowed that the journey was what he most wanted, and needed.

As for us, our journey is almost complete. Our journey has been relatively comfortable: riding in a car, stopping when we feel like it to take a walk or look at scenery, sleeping in motels. Our journey has been relatively quick: a matter of days, not weeks or months. But as we drove down out of the Sierra Nevadas, down into the wide Central Valley, through the traffic of Sacramento, I feel a change in myself — not enough of a change, but a change. That’s what the early emigrants on the California Trail were looking for: a change; a change in circumstances, but also I think an inner change. Mark Twain was looking for a change in circumstances when he went by overland stage to Carson City, Nevada, and after seven years in the West found that what had changed most was — not external circumstances — but himself.

We kept on driving west, driving towards the sun setting over the Coastal Range, the western-most range of mountains in this part of North America.

Above: The Coastal Range near Winters, Calif.

Somewhere beyond those purple mountains lies San Francisco Bay, on the edge of which we live; and beyond one last ridge of the Coastal Range lies the Pacific Ocean, extending into vastness beyond the limits of sight. And as we see the sun set behind the mountains, we know that we will not reach our final destination before night settles in on us.