Nathan Johnson was an African American who is best known for welcoming Frederick Douglass into his house on Douglass’s first night of freedom in New Bedford, Mass. In the late 1830s, Johnson was a member of the Universalist church in New Bedford, then served by the staunchly abolitionist minister John Murray Spear.

A few years ago, I wrote a brief biography of Nathan Johnson. Since then, online searching of federal and state census records has gotten much easier, and I easily tracked Johnson in Massachusetts through three U.S. Censuses. Of greater interest, I believe I have found him in the 1852 California census.

First, here are the U.S. Census records from Johnson’s time in New Bedford (note that links will require you to sign in to FamilySearch.org to view the photos of the census records):

1830 U.S. Census [see image 71 of 102]: Nathan Johnson listed as head of household; only white persons are enumerated in the census, and no one is enumerated in Nathan Johnson’s household, leading to the conclusion that he is black. Most probably our Nathan Johnson; I could find no other Nathan Johnson listed living in New Bedford.

1840 U.S. Census [see image 43 of 204]: Nathan Johnson, head of household; in the household were on black male between 10 and 24 years old, one black male between 33 and 55 [probably Johnson himself], 3 black females between 10 and 24, 1 black female between 24 and 33, 2 black females between 33 and 55, and one black female over 55. This corresponds well enough with what we know of Johnson’s household. Most probably our Nathan Johnson; I could find no other Nathan Johnson listed living in New Bedford.

1850 U.S. Census [see image 111 of 388]: Although I believe that Nathan was in California by 1850, his wife, Mary “Polly” Johnson may have expected him to return soon, and so reported him to the census taker. The household is listed as follows: Nathan Johnston [sic], 54 year old male, black, occupation “Waiter,” owning real estate valued at $15,500, born in Penna.; Mary J. Johnston, 60 year old female, black, born in Mass.; Charlotte A. Page, 10 year old female, black, born in Mass.; Clarissa Brown, 14 year old female, black, born in Ohio; Emily Brown, 75 year old female, black, born in Penna.; George Page, 17 year old male, black, occupation laborer, born in Mass. Probably our Nathan Johnson; I could find no other Nathan Johnson listed living in New Bedford.

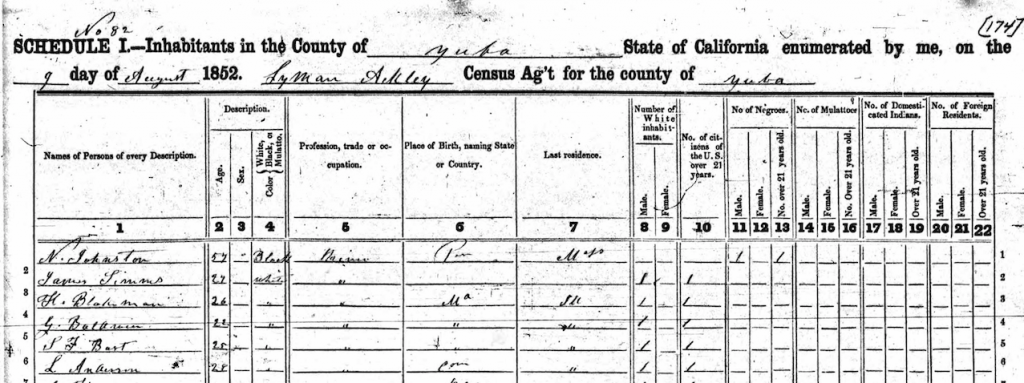

Next, the 1852 California census:

An N. Johnson is listed as living in Yuba, Calif, age 57, born in Penna. In consulting other records, I had tentatively placed Nathan Johnson in Yuba City, so this could possibly be our Nathan Johnson. (No image of the census records available.) This was the only record I could find that matched our Nathan Johnson in California. Update on 8/29: Lisa deGruyter, who commented below, sent me the image of the 1852 California census, and reveals that this N. Johnson was white, probably age 36 (the handwriting is hard to read), born in Germany, and last lived in Louisiana — clearly not our Nathan Johnson.

Further update on 8/30: Lisa deGruyter has found our Nathan Johnson in the 1852 California census. He is listed as N. Johnston, age 54, black, occupation Miner, born Penna., last residence Mass., currently living in Yuba County.

And I was unable to find any further U.S. Census records of Nathan Johnson living in Massachusetts or California. Update on 8/29: Lisa deGruyter found a Nathan Johnson listed in the 1855 Massachusetts census as living in New Bedford, with occupation given as “Cal.” (in quotation marks), which, as Lisa points out, could mean that Nathan was working in California; listed as a black male, age 55, with Mary Johnson living with him; his birthplace Penna. This is almost assuredly our Nathan Johnson, and reveals that Polly still thought of his removal to California as in some sense temporary.

The most interesting bit of information is the 1852 California Census, which seems to confirm Johnson’s presence in Yuba. The most interesting piece of information is finding Nathan Johnson listed in the 1852 California Census as a miner in Yuba County. But where he was in California from 1852 to 1873 remains a mystery. Lisa deGruyter found a little more information in a National Park Service Research Report “California Pioneers of African Descent,” available here.

Nathan Johnson returned to Massachusetts after his wife’s death, in 1873. His gravestone in Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford states that he died Oct. 11, 1880, “aged 85 years,” with the legend “Freedom for all Mankind.” The death records for the City of New Bedford list his birthplace as Virginia, and it is possible that prior to the Civil War he gave a free state as his birthplace because he had emancipated himself from slavery.