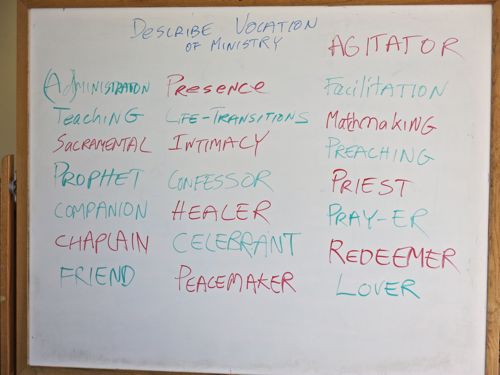

In a previous post I outlined some reasons why I don’t want to wear a preaching gown. In this post, I’ll do my best to give some of the many good reasons why Unitarian Universalist ministers should Geneva gowns, or other types of preaching gowns.

First, women ministers are held to impossible standards of dress, and for them a preaching gown makes sense. I have heard from many women ministers about the comments they have to endure from congregants about their clothes. I’ve heard about other women giving backhanded compliments on articles of clothing, compliments that are really criticisms. I’ve heard about men making inappropriate comments on how “sexy” or “attractive” a woman minister looked. As a man, I could deal with that kind of comment by wearing exactly the same kind of clothes all the time (which is in fact what I do), but women are held to a different standards and if they don’t wear a variety of clothes they are subjected to criticism. So if I were a woman minister, I wouldn’t want to deal with this kind of bullshit, and I’d seriously consider wearing a preaching gown.

Second, ministers who are not white typically experience varying levels of racism in our predominantly white Unitarian Universalist congregations. As an example, recently I heard about a minister of color who was told that they were very well-spoken — well of course they are, they have been trained in the art of public speaking, as have all ministers — white male ministers don’t receive this sort of backhanded compliment (sadly, white women do hear similar comments). If I were a person of color and a minister in a Unitarian Universalist congregation, chances are good that I’d want to wear a preaching gown.

Third, there are ministers who are poor dressers. I’m one of those ministers. I simply don’t pay attention to clothes most of the time. On one memorable occasion, I showed up at church on Sunday morning wearing a coat and trousers from two different suits. I frequently forget to fasten collar and cuff buttons. I have poor taste in ties. I try to remember to pay attention to my appearance, but I frequently forget; it’s not that I don’t care, I’m simply not aware. Ministers like me might to do better to wear wear a preaching gown, to save our congregations from occasional embarrassment. In my case, however, I’m sure I’d find ways to look slovenly in a preaching gown; the gown might hide some of my sartorial blunders, but not all of them.

Fourth, a preaching gown is a symbolic tie to Unitarian Universalist history. It’s not a wholly bad thing to be descended from the Protestant Reformation. Some of our most cherished values — freedom of individual conscience, the priesthood and prophethood of all persons, etc. — derive from the Reformation. Ralph Waldo Emerson wore a preaching gown, as seen in Daniel Chester French’s sculpture of the seated Emerson. Wearing a preaching gown can symbolize the tie to our most brilliant Unitarian minister, and to a host of other Unitarian and Universalist and Unitarian Universalist ministers.

In short, there are very good reasons for a Unitarian Universalist minister to wear a preaching gown. There are very good reasons for Unitarian Universalist congregations to want their minister to wear a preaching gown. Perhaps most importantly, given the persistent and pernicious sexism and racism in Unitarian Universalism (which is a reflection of the racism and sexism in our wider society), preaching gowns make a great deal of sense. Wearing a preaching gown can serve as a symbol that the person wearing it is a highly trained and skilled professional. Well-meaning white parishioners, and parishioners of all genders, may need this weekly reminder. The reminder of professional competence offered by preaching gowns might also be useful for ministers who are young, disabled, LGBTQ+, etc.

Indeed, white male ministers like me should probably consider wear preaching gowns to show solidarity with our ministerial colleagues. However, this must be balanced against another consideration. In my experience dealing with the aftermath of ministers who engage in unethical behavior and misconduct, I have a strong sense that misconducting ministers use all the little signs and symbols of authority to insulate themselves from being held accountable for their ethical violations. I believe some misconducting ministers have used the symbolic power of a preaching gown to allow them to hide from accountability. So white male ministers who choose to adopt the signs and symbols of ministerial power — preaching gowns, titles, and the like — must be careful to ensure that there are robust institutional structures in place to hold them accountable for their behavior. Actually, all ministers should make sure there are robust institutional structures in place to hold them accountable, but white male ministers need to be especially sure of this.

For me personally, the decision on whether or not to wear a preaching gown comes down to two competing demands. If I were to wear a preaching gown, I could express solidarity with non-white and non-male ministers. Balanced against that is my strong sense that wearing a preaching gown can serve as one of those little things that can serve to insulate ministers from ethical accountability. For me — not for anyone else, mind you, just for me — the balance is tipped in favor of any slight increase in ethical accountability. But I think for most ministers, and for most congregations, the balance will be tipped the other way.