I finally finished writing a short essay titled “Reimagining Sunday school” for my curriculum website. This essay has been in the works for a while, both as a response to the “death of Sunday school” movement, and as a response to the de-funding of religious education programs that we’ve been seeing denomination-wide. I’m copying the entire essay in below the fold, or you can read it on my curriculum website.

Continue reading “Reimagining Sunday school”Tag: curriculum

The evolving state of religious education

I am increasingly convinced that the pandemic is accelerating a number of trends that are going to change the way we do religious education in our local congregations fairly quickly. However, I don’t these trends should lead us to proclaim either the “post Sunday school era” or “the death os Sunday school.”

And before you get too excited (“Yay, the death of Sunday school!”) or too sad (“Nooo, I miss Sunday school!”), let’s look at a couple of the trends that affect religious education, trends that are being accelerated by the pandemic…..

1. Current trends affecting religious education

2. Where we came from, 1781 to the present

1965-2005

1900-1965

1781-1900

3. Why the “post Sunday school” advocates are right

4. Why the “post Sunday school” advocates are wrong

5. Expanding our religious education possibilities

6. The whole church as curriculum

7. New models for funding

8. Final thoughts

———

1. Current trends affecting religious education

First and foremost among current trends, most American congregations face looming financial difficulties. Staff costs continue to outpace inflation, driven in part by health insurance costs. Staff costs in Unitarian Universalist congregations are also under pressure because we expect our professional staff — both ordained ministers and lay religious educators — to have at least a four year college degree, and often three or more years of graduate study; staffers have to pay off their college debts, and that means they need relatively high salaries. Finally, there’s always Baumol’s Cost Disease: American congregations represent an “technologically stagnant sector” which means congregations experience “above average cost and price increases.” The amount each person gives to a congregation has to increase faster than inflation, just so the congregation can provide the same amount of services.

Continue reading “The evolving state of religious education”Patol House

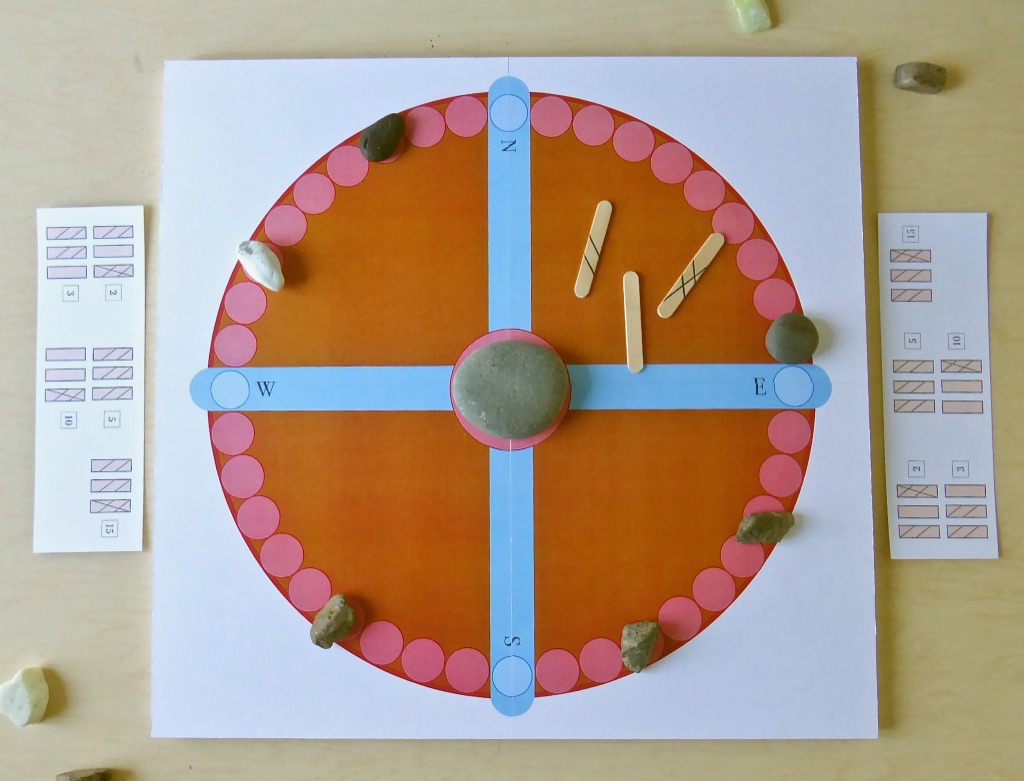

While developing a curriculum for middle elementary grades, I found an interesting game, “Patol House,” originally played by Native Americans in New Mexico. I found this game in the book Handbook of American Indian Games by Allan and Paulette Macfarlan (Toronto: General Pub., 1958; reprint, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Pub., 1985). The Macfarlans are recreating games for use by middle class white kids in summer camps in the 1950s, and no doubt they have modified the rules to this game somewhat. I have further modified the rules, turning this into a board game suitable for use indoors in a multi-racial Sunday school classroom; and I further modified the rules to fill in a gap or two that we found in the Macfarlans’ rules during test play.

Sample game play with adults showed this can be a fun game. It’s supposed to be a game of skill and strategy, not of luck — the skill comes in being able to throw the counting sticks to yield the number you want; the strategy comes in planning your moves to “kill” opponents’ horses. In our sample play, we gained enough skill to throw the desired number maybe one out of ten times, so it was mostly a game of luck for us. But even as a game of luck, it was enjoyable to play.

With no further ado, here’s how to make and play the game:

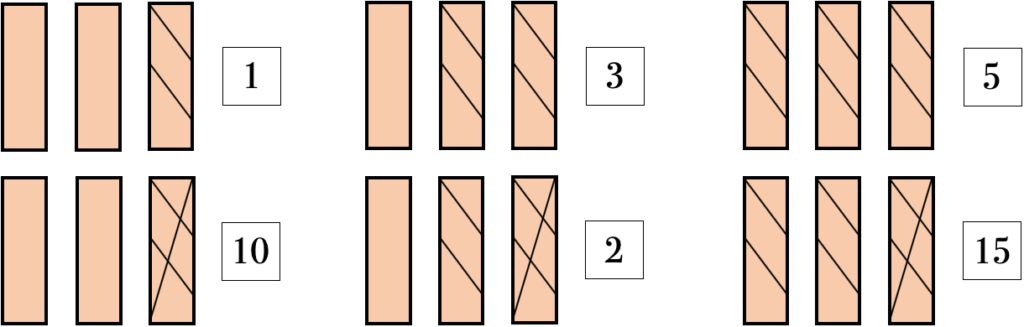

Making the game: According the the Macfarlans, the Indians used a game board of 40 stones arranged in a circles, with 4 gaps between the stones; the gaps are “rivers.” The design shown in the photo below reproduces this game board on paper; the blue stripes are the “rivers.” I printed the design in halves, on two 11 by 17 inch pieces of cardstock; then gluing the cardstock to foamcore to make a 17 by 17 inch game board. The counting sticks are popsicle sticks that are shortened; the sticks are marked (based on Tiwa Indian designs) as follows: all three sticks have two hatch marks on one side; two are left blank on the reverse side, while one is marked with three hatch marks on the reverse. A flattish stone goes in the center; this is to bounce the counting sticks off. I made two cards showing how to score the throws of the counting sticks. For playing pieces, I found some small stones, as you can see in the photo below; however, these were not very satisfactory, and I have since substituted colored game pawns.

(Notes on making the game: 1. The point of this game is not to try to recreate an utterly authentic Native design, but to make a game that is easily playable. 2. The file for the game board is something like 5400 x 5400 pixels at 300 dpi and too big to post here, so you’ll have to draw your own game board. 3. I’m prototyping the game using the Board Games Maker Web site; when they ship it to me I’ll post a photo on this blog.)

This game works best with 8 or more players. If you have fewer players, give each player two horses; players take a separate turn for each horse.

Setting up the game:

Put the stone in the center of the game board. The playing pieces, called “horses,” remain off the game board until a player plays them.

Throw the counting sticks to see who goes first:

Hold the three counting sticks in your hand about a foot above the game board. Bring your hand down, and release the sticks about 6 inches above the stone (but no closer). The sticks hit the stone, bounce, and fall with one face or another showing.

The diagram below shows how many points you get, depending on which sides of the counting sticks are showing. The player with the highest number of points goes first.

Game play:

The first player throws the counting sticks, and, starting from a blue circle nearest to where they are sitting, moves their horse that number of spaces. Players may move either clockwise or counterclockwise as they wish, but once they begin moving in one direction they must keep moving in that direction in subsequent turns. However, if they throw a 10, this would place their horse in a river. Horses may not land in rivers. Whenever a throw lands their horse in a river, the player must throw the counting sticks again until they throw a number that will not land their horse in a river.

The other players may begin from the same river that the first player started from, or from a different river. Again, they may move either clockwise or counterclockwise, but once they begin moving in one direction they must keep moving in that direction.

Player’s horses may pass over other players horses. But if one player’s horse ends up on the space occupied by another player’s horse, the other player’s horse is considered dead and must start over. A player may have to start over several times during the course of a game.

If you start over, you must start in the same river you started in before (that is, in the same blue circle). However, if you start over, you can again choose to go either clockwise or counterclockwise—though again, once you choose a direction you have to keep going in that direction, until you have to start over again.

Winning the game:

The first player whose horse makes it all the way around the circle, back to their starting point or past it, wins the game.

Strategy: For good players, this is a game of skill. A good player can hold the sticks in their hand and bounce them in such a way as to get the number they want. But be sure to release your hold well above where the sticks hit the stone, so you’re not accused of cheating.

Paper bag puppets for a Jataka tale

I’m in the middle of writing curriculum for middle elementary grades, and here’s a children’s craft project I just developed for this curriculum. These are puppets for acting out the story-within-the-story of the Buddhist Jataka tale “The Little Tree Spirit” (which you can read on my old blog here).

You will need:

patterns that you print and cut out ahead of time

glue sticks or paste

scissors

pencils

black magic markers

paper bags (lunch bag size, 5 x 10 in. folded)

paper or card stock in the following colors:

—pink (for noses and mouths)

—white (for eyes)

—dull green (for Little Tree Spirit)

—bright green (for Great Tree Spirit)

—orange (for Tiger)

—yellow (for Lion’s head)

—brown (for Lion’s mane)

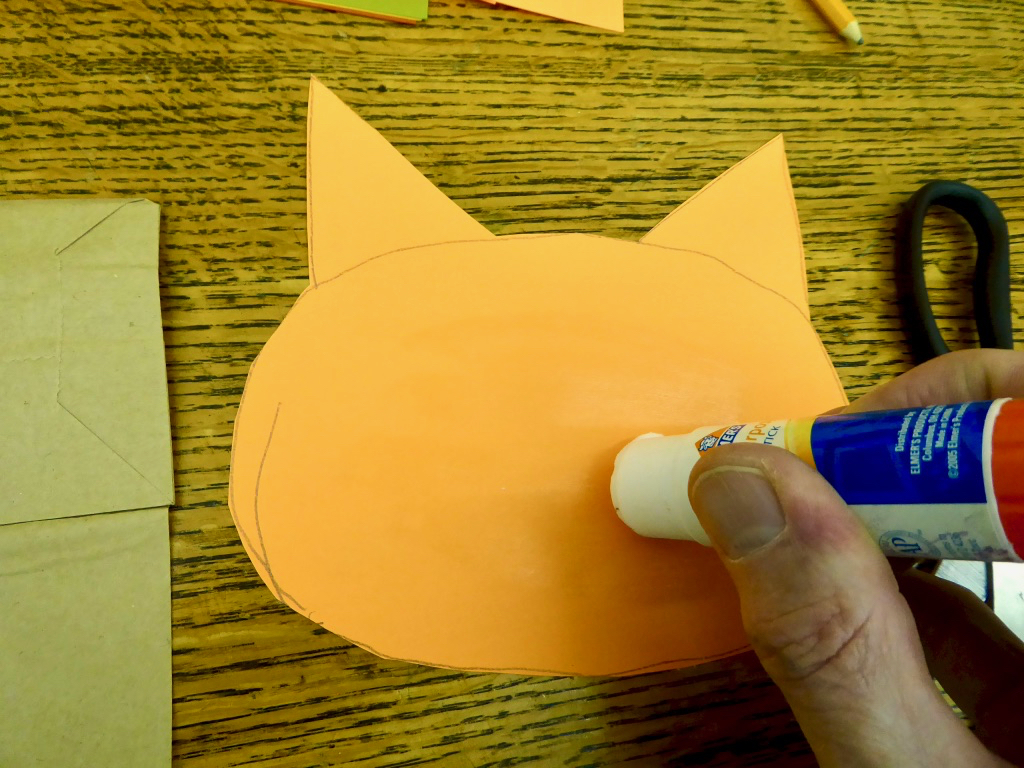

Let’s start by seeing how the Tiger is made.

(1) Cut out the head, attach it to the paper bag:

Trace the head shape from the patterns or draw it freehand on orange paper, then cut it out. Glue the head to what is the usually bottom of the paper bag.

(2) Add details to the head:

Cut out the nose from pink paper, and two eyes from white paper. Glue on the eyes and nose, and draw pupils in the eyes. Using the black magic marker, draw stripes and whiskers on the tiger as shown above.

(3) Add the mouth:

Cut out the mouth, and fold it at about one third of the way across the diameter (about one inch from the edge). Glue the mouth in the flap formed by the bottom of the paper bag where it’s folded over, as shown in the drawing. You want a little bit of the pink mouth to show below the head of the puppet.

(4) Try your puppet:

Put your hand inside the puppet, and make sure the mouth looks right when you open and close the puppet’s mouth.

(5) Make the other puppets:

The rest of the puppets are made in much the same way. (1) For the Lion: use the same head pattern but cut the head out of yellow paper; then cut a mane out of brown paper and glue the head on the mane. (2) For the Little Tree Spirit: use the tree pattern and cut the tree out of green paper. (3) For the Great Tree Spirit: use the mane pattern, cutting the shape out of green paper for the “head.”

Now you have all the puppets you need to act out the story. They’re kind of crude, but they’re effective.

Kisolo

I’m in the process of writing a curriculum for middle elementary that will include a story from the Kongo religious tradition, “Spider Steals Nzambi Mpungu’s Heavenly Fire.” As a supplementary activity, I’m planning to include instructions for Kisolo, a traditional Congolese game that resembles the well-known Mancala game that’s commercially available in the U.S. So here’s my first pass at Kisolo rules, somewhat simplified for middle elementary grades. (If you play this game, let me know what you think of the rules.)

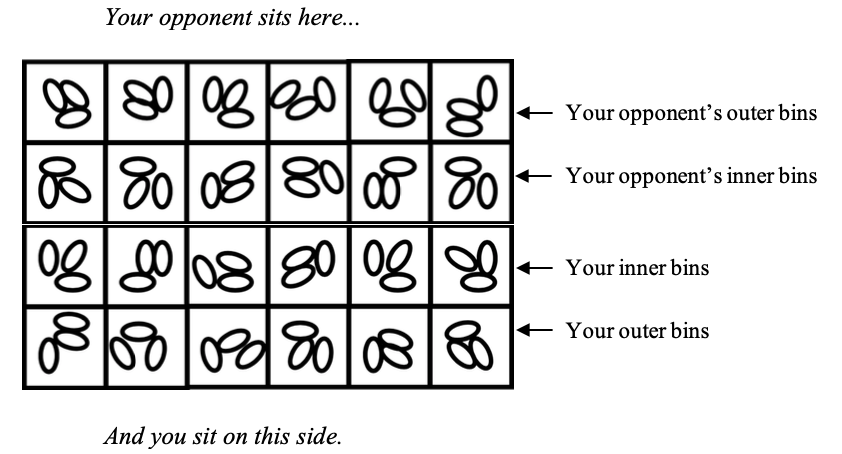

To make a Kisolo board: Take two egg cartons, and cut their lids off. Tape them together to make a game board with six by four holes. (Most traditional Kisolo boards are four by seven holes in size, but a smaller board is allowable and makes for shorter game play.) You can also use he commercially available Mancala boards — take two of them, place them side by side and ignore the large bins at the ends of the boards.

To set up the board: Place three “seeds” in each bin. You can use actual bean seeds, or small glass tokens or what-have-you, for seeds. (For a faster game, plant only two seeds per bin.)

To start:

Two players sit at the long sides of the game board opposite each other. The twelve bins on your side belong to you, and the twelve bins on your opponent’s side belong to them. Each player has six “outer bins” (the row of bins nearest to them) and six “inner bins” — see the diagram above.

To play:

Youngest player starts.

When it is your turn, see if one of your inner bins contains seeds AND your opponent’s inner bin opposite it contains seeds. (If that’s true of more than one of your inner bins, just pick one; OR if you can’t capture any seeds, see below.)

Then remove all the seeds from your inner bin, plus the seeds in the corresponding bin that belongs to your opponent, and any seeds in your opponent’s outer bin that’s next to that inner bin.

Now “sow the seeds,” that is, starting with the inner hole you’ve just emptied, place one seed in each of your holes and continue counterclockwise sowing seeds only into you holes, until you have sown all the seeds.

If your last seed falls in one of your inner holes, then you ALSO get to remove all the seeds from your inner bin, plus the seeds in the corresponding bin that belongs to your opponent, and any seeds in your opponent’s outer bin that’s next to that inner bin. Then you sow the seeds as before—it’s like you get another turn (but after that your turn is over).

IF YOU CANNOT CAPTURE ANY SEEDS, then empty the seeds out of any one of your holes and sow those seeds counterclockwise into your own holes.

To win the game:

Capture all the seeds in your opponent’s INNER holes (doesn’t matter how many seeds are in the OUTER holes).

Note that some games will end in a draw, where neither player can win. If it feels like the game is going nowhere, the players can agree to a draw.

AAR religious literacy guidelines

The American Academy of Religion (AAR) has released a set of “Religious Literacy Guidelines” setting minimum standards for all graduates of two- and four-year colleges in the United States. An excerpt from these guidelines summarizes the minimum knowledge about religion that all college graduates should have:

“‘Religious literacy’ helps us understand ourselves, one another, and the world in which we live. It includes the abilities to:

— Discern accurate and credible knowledge about diverse religious traditions and expressions;

— Recognize the internal diversity within religious traditions;

— Understand how religions have shaped — and are shaped by — the experiences and histories of individuals, communities, nations, and regions;

— Interpret how religious expressions make use of cultural symbols and artistic representations of their times and contexts;

— Distinguish confessional or prescriptive statements made by religions from descriptive or analytical statements…”

It turns out that in 2010, AAR released a set of religious literacy guidelines for K-12 students. The K-12 guidelines are also well worth reading. They include some basic premises from the scholarly discipline of religious studies, premises which AAR considers essential for teaching religious literacy:

— religions are internally diverse;

— religions are dynamic and changing; and

— religions are embedded in culture.

Anyone who has gained basic familiarity with religious studies at any time in the past 20 years will find no surprises in either set of guidelines. For example, even though these guidelines are new to me, I’ve been using the underlying premises for at least a decade, as I develop curriculum on religions. But though there’s nothing new here, by formulating these guidelines, AAR has done us all a favor: now we have checklists that we can use to assess how well curriculums promote religious literacy.

We can also use these guidelines for some rough-and-ready assessment. When I look at these guidelines, I see that for the most part Unitarian Universalist adults do not have solid religious literacy, e.g., many UU adults are unaware of the immense religious diversity within Christianity, many UU adults are not able to discern accurate and credible knowledge about religious traditions, etc. This becomes problematic when adults with a low degree of religious literacy teach religion to children; and this suggests that curriculum development needs to include basic religious literacy knowledge for adults teachers, as well as content for children.

Exodus: The Card Game

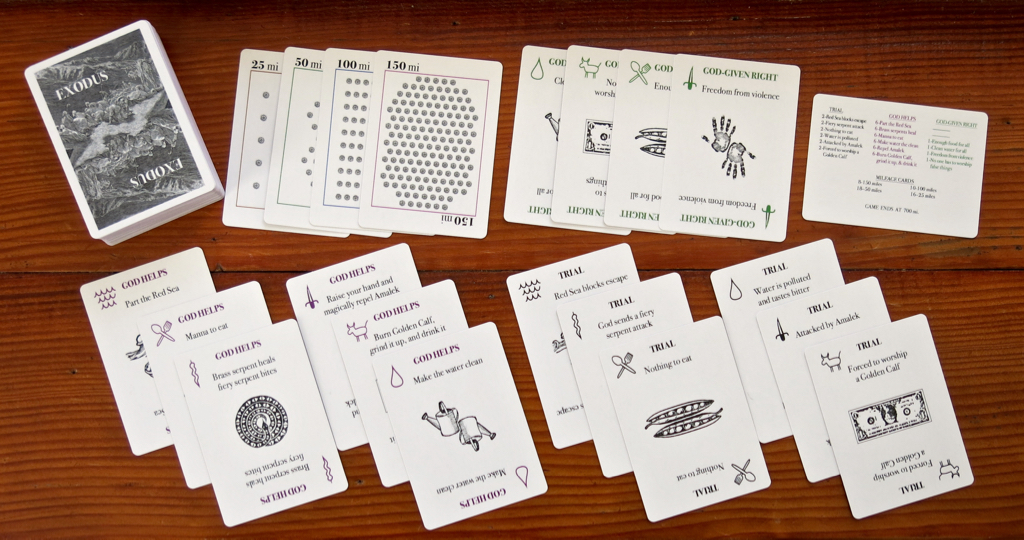

A few months ago, I wrote about prototyping “Exodus: The Card Game,” a game based on the wanderings of the Israelites. After lots of play with both kids and adults (and lots of changes to the rules), prototyping is finally done. I made 6 decks using the online printer Board Games Maker; the printing quality is excellent, and here’s what a deck looks like:

One of our curriculum goals in our Sunday school is to play more games. “Exodus: The Card Game” is designed to supplement an upper elementary or middle school unit on the Hebrew Bible. Once you learn the rules, play takes about 15-20 minutes, so it fits nicely into a typical Sunday school class time. And the rules are fairly simple and straightforward; I’m including them below the fold so you can get an idea of the game.

The only problem with this game is the price. I bought 6 decks, and the price including shipping and handling came out to just under $25 per deck — pricey for a card game. (If I printed 1000 decks the price would drop to about $6 per deck, but what would I do with 1,000 copies of this game?)

If you’d like to buy a copy of the game, email me and I can get you a single copy for about $27. (There’s a price break at 6 copies, which knocks approximately $2 off the price; next price break is at 30 copies.) If you’re going to the Pot of Gold religious education conference in Sacramento on Sept. 29, I’ll have a few extra copies of the game to sell.

Principles behind Sunday school Ecojustice class

Here are some of the principles behind the Ecojustice class taught at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA) for the past five years.

Ecojustice class is a Sunday school program for gr. 6-8. Ecojustice class is a learner-centered program, with a flexible curriculum that can follow the interests of the teens and the teachers. We have a firm commitment to making the class as hands-on as possible — an emphasis on doing, rather than discussion. Rather than just projects done by one individual and intended for themselves, our projects tend to be done as a group and intended for use by the class, congregation, or a wider community. Ecojustice class can best be described as a “emergent curriculum,” meaning we’re often making it up as we go along; nevertheless, we have evolved some pretty firm organizing principles which may be of use to others.

Our definition of “ecojustice”:

A sign is posted in the classroom which gives our definition of “ecojustice”:

Ecojustice =

— humans treating other humans with dignity & respect

AND

— humans treating other organisms & the whole ecosystem with dignity & respect

If teens ask: “Why can’t we just say ‘Ecojustice means humans treating each other and the rest of the ecosystem with respect’?” — we can explain that white environmentalists have been criticized because they worry more about non-human organisms than they worry about humans who have a different skin color. So we want to make sure we always remember that environmental action cannot be separated from human justice.

Basic class plan is the same every week:

I/ Attendance & chalice lighting (typically indoors)

II/ Check-in (typically indoors)

III/ Reading (typically indoors)

IV/ Project for the week (most often outdoors)

V/ Closing circle (often outdoors)

Reading: Each reading is related in some way to ecojustice. We adults can read the reading, or ask the teens if one of them would like to read it. Then maybe have a brief conversation about what the reading tells us about ecology, ecojustice, or the natural and human worlds.

Project for the week: Projects may last from 1-4 weeks. Teachers pick projects based on their interests and abilities. We try to include a conversation with each porject about why we are doing the project: “what does this project have to do with ecojustice?” This can take place while we’re working, or as part of the closing circle.

Closing circle: During closing circle, have the teens say one thing they learned, or one thing they’re taking away from this class. End with the UUCPA unison benediction (used in all classes); the unison benediction is posted in classrooms in 4 languages, reflecting languages spoken by people in our congregation (English, Spanish, German, Hindi; working on a Mandarin version).

Topic areas:

We relate any project that we develop to one of seven topic areas. Those topic areas are listed below, along with sample projects that we have either completed or plan to carry out (in parentheses).

1. Food

Tire Garden — based on the UUSC Haiti tire garden project

Ongoing Gardening — digging, planting, weeding, watering, etc.

Cooking projects — using, e.g., organic ingredients

2. Energy

Rocket Stoves — based on a design by Larry Winiarski

Solar Cooking — using various solar ovens (solar s’mores esp. popular)

3. Water

Rain Barrel — installed a rain barrel; use the water to irrigate the gardens

Clay Pot Irrigation — low-water use irrigation method

(Bucket Drip Irrigation — low-water method for irrigating garden)

4. Waste

Composting — assembled two composting bins; maintain them

(Build a composting toilet)

5. Habit and Shelter

Wildlife — “tracking pit”; invertebrate observation; building birdhouses

Native Plants — tour of church’s native plant garden

Habitat for native pollinators — making “bee houses”

Support local homeless shelter which stays at our church in Sept.

(Using Natural Herbs — planned visit from a local herbalist)

(Natural Dyes — tie-dye using redwood cones and fennel)

6. Earth and Air

Disaster Plans — making a personal “go-kit” in case of wildfire evacuation

(Global climate change project — but how to make it hands-on?)

7. Toxics in the Environment (new category added in 2018)

(E-waste)

(Phytoremediation — using plants to remove toxics from the soil)

More info about each of these topic areas is below.

Update, June, 2022: See the updated curriculum online here: http://kj6zwr.org/ecojustice/. The curriculum has been completely restructured, based on several years of teaching.

Continue reading “Principles behind Sunday school Ecojustice class”Game development

In our congregation, we decided we need to pay more attention to resources that can support the curriculums. We want resources that are fun for kids, don’t feel like weekday school, don’t require any teacher preparation, and support the learning that takes place in the regular curriculums.

Like, for example, board games and card games. We already use a couple of board games in our Sunday school: (1) Wildcraft, a cooperative board game that teaches about herbs, supports some of our ecology courses; and (2) Moksha Patam, a board game that simulates karma, rebirth, etc., supports one of our world religions curriculums.

Ideally, we’d like to have one relevant board game per quarter per age group that we can give to teachers. And while we were talking this over in the curriculum review committee, I started dreaming up a card game about Moses leading the Israelites to freedom across the wilderness. Then I had a day of study leave today, so I could prototype this game, provisionally called: “Exodus, The Card Game.”

The game borrows its basic structure from the classic card game Mille Bornes (if you don’t know Milles Bornes, it will be easier to understand this blog post if you first read the Wikipedia article).

Although I’m borrowing the basic structure of the game from Mille Bornes, there are significant differences. Mostly, Exodus is a faster-paced game, more suited to the short time allotted to Sunday school classes. And I had to make other changes to fit the narrative of the book of Exodus — I wanted to make sure that as you play you get some sense of the narrative of Exodus…such as the fact that G-d released fiery serpents that attacked the Israelites, but then G-d told Moses to make a brass serpent that would heal serpents bites (Num. 21:6-8). Before researching this game, I didn’t even remember about the fiery serpents. It’s a pretty strange thing to include in the narrative, and one of my learning goals (and part of my theological interpretation) for Exodus, The Card Game is to help kids understand that the story of Exodus is pretty weird. It’s not trying to be an accurate historical account, nor is it some kind of scientific explanation — rather, it is a narrative filled with fantastical elements that reveal G-d’s character.

My other big learning goal and theological component for the game is, not surprisingly, to give some understanding of G-d’s character. First and foremost, G-d is not all kittens-and-rainbows, as for example when G-d sends the fiery serpents to bite the Israelites. Second, G-d does not follow human logic and is ultimately unknowable by humans; this is symbolized for the Israelites in part by spelling G-d’s name without vowels: “YHWH” (this idiosyncratic spelling is retained in the game in the English name for G-d). Third, while G-d is not omnibenevolent, G-d does want justice for humans and for the land; this theological interpretation of G-d’s character is communicated by the social justice flavor of the G-d Given Right Cards. A lesser fourth point is that G-d’s power do have some limits to them; G-d is not wholly omnipotent. So it is the game tries to help the players get a small sense of G-d’s character.

If I ever put the game into production, I’ll let you know how you can get a copy….

Update 4/14/18: Major revisions to game rules and narrative now complete. I won’t revise this post any more; any future rules revisions will be incorporated into the production game (if it’s ever put into production).

Update 9/7/18: The game is now available as a professionally-produced card game, so I’m removing the outdated rules and card designs. To see the final game, click here.

Teaching about white supremacy

How can we teach young people about “white supremacy” within the constraints of a typical Sunday school? What are some of the theoretical considerations, and what are some practical considerations?

One of my professional organizations, the Liberal Religious Educators Association (LREDA) has called on Unitarian Universalist religious educators to participate in a “white supremacy teach-in” in the coming weeks, to follow up on the denominational brouhaha which led to the resignation of Peter Morales from the presidency of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).

This is a great call to action, but where do we come up with pedagogical strategies to teach children and teens about white supremacy? I’ll get to practical suggestions after a brief review of theoretical resources; although if you’re a hands-on educator you may want to go straight to practical suggestions, skipping over theoretical considerations which may seem pretty remote from actual children and teens.

Theoretical resources

Practical suggestions

Let’s start with the obvious: with bell hooks and her book Teaching to Transgress, and with Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Both these books provide useful theoretical perspectives. However, in my experience these books are not very useful for children and young people since they focus on persons age 18 and up.

Lev Vygotsky is another obvious source of pedagogical insight. Vygotsky’s theories provide us with such well-known concepts of “scaffold-and-fade,” and the zone of proximal development. For a helpful summary of zone of proximal development, I like Seth Chaiklin, “The Zone of Proximal Development in Vygotky’s Analysis of Learning and Instruction,” in Kozulin et al., Vygotsky’s Educational Theory and Practice in Cultural Context [Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003]). Chaiklin makes a number of points that might prove helpful. Chaiklin points out “the zone for a given age period is normative, in that it reflects the institutionalized demands and expectations that developed historically in a particular societal tradition of practice,” thus implying a strong connection between institutional demands and children’s development. Chaiklin also carefully defines the technical meaning of “imitation” in Vygotsky, and then points out that “the main focus for collaborative interventions is to find evidence for maturing psychological functions, with the assumption that the child could only take advantage of these interventions because the maturing function supports an ability to understand the significance of the support being offered”; thus, there are definite psychological and developmental limitations to the amount of learning that can take place within the child.

And in a Unitarian Universalist context, I believe it’s helpful to connect Vygotsky’s collectivist understanding of learning and development with James Luther Adam’s theological conception of the congregation as a voluntary association in mass democracy. Adams’s conception of congregations as voluntary associations helps us understand that face-to-face and personal encounters within a congregation help prevent the atomization of the individual, which in turn can prevent mass democracies from hurtling towards totalitarianism. So Vygotsky teaches us that “a person is able to perform a certain number of tasks alone, while in collaboration, it is possible to perform a greater number of tasks”; and Adams’s work suggests not only that the congregation is a place where we can collaborate together to support a liberative and liberal democracy, but also that the congregation as a whole can support the developmental growth of children and teens towards healthy maturity.

Another useful theological resources is William R. Jones’s essay Theism and Humanism: The Chasm Narrows. In this essay, Jones makes a very helpful connection between theism and the “left wing” of theism: both are humanocentric worldviews, in which it is up to humans to effect positive change. Jones help us see that we can’t wait around for some Daddy God to bail us out — for that matter, nor can we wait around for Big Daddy Science to bail us out — a humanocentric point of view acknowledges that it’s up to us humans to effect change. (Jones makes the same point in his book Is God a White Racist?)

For theoretical resources specific to religious education, I’d turn to my other professional organization, the interfaith and international Religious Education Association (REA), which includes both scholars and practitioners. Over the years, the REA has published or presented interesting scholarship on how to teach liberation and social justice; the most notable recent instance is REA’s 2012 conference “Let Freedom Ring”: Religious Education at the Intersection of Social Justice, Liberation, and Civil/Human Rights. So REA conference proceedings and the REA journal Religious Education have plenty of theoretical material that would help in teaching about white supremacy. The problem with the REA publications is that you have to read through a great deal of material to find relevant articles, and even then you often have to do some translation from another cultural contexts (e.g., figuring out how an article outlining teaching peace to Israeli and Palestinian youth might translate to a U.S. context).

Beyond REA publications, there are plenty of progressive religious educators who have written books that offer resources for this kind of endeavor. A couple of books that come immediately to mind are John Westerhof’s book Learning through Liturgy, and Robert Pazmino’s Foundational Issues in Christian Education; Westerhof’s book helps usnderstand how learning takes place in and through worship services; and I have found Bob’s book extremely helpful in confronting my own internal inclinations and biases. A few Unitarian Universalists with anti-Christian biases and prejudices might be repelled by these books; but I’d suggest that the exercise of tamping down anti-Christian biases long enough to find the good in those books could be a useful preparatory exercise for those who have a serious desire to teach against racial bias and prejudice.

As an educator, I have been greatly inspired by Marcia Chatelaine’s workshop “Talking to Students about Ferguson,” given at Ferry Beach Conference Center in July, 2015. Chatelaine, a professor of history at Georgetown University, helped me understand how intersectionality could be a useful pedagogical strategy. Her workshop also helped me to understand how to get past the strong emotions elicited by Ferguson; she suggested addressing Ferguson from within one’s own area of disciplinary expertise. Thus, as a historian, she could talk about the history of Ferguson as a white-flight suburb, using her are of disciplinary expertise to generate insight.

Finally, I would also turn to the works of educational philosopher Maxine Greene. In particular, I have found her short essay “Diversity and Inclusion: Towards a Curriculum for Human Beings” to be foundational for the kind of liberative religious education I hold us as an ideal. I’ll give one brief excerpt from this essay that might serve as an inspiration for a suitable pedagogic practice for teaching about white supremacy:

“[T]here has been a prevalent conception of the self (grand or humble, master or slave) as predefined, fixed, separate. Today we are far more likely, in the mode of John Dewey and existentialist thinkers, to think of selves as always in the making. We perceive them creating meanings, becoming in an intersubjective world by means of dialogue and narrative. We perceive them telling their stories, shaping their stories, discovering purposes and possibilities for themselves, reaching out to pursue them. We are moved to provoke such beings to keep speaking, to keep articulating, to devise metaphors and images, as they feel their bodies moving, their feet making imprints as they move towards others, as they try to see through other’s eyes. Thinking of beings like that, may of those writing today and painting and dancing and composing no longer have single-focused, one-dimensional creatures in mind as models or as audiences. Rather, they think of human beings in terms of open possibility, in terms of freedom and the power to choose.”

I wanted to end with that passage from Maxine Greene because it points the way to the kind of flexible, learner-focused teaching that I want to do.

When I translate these (and other) theoretical resources into practical pedagogy for young people in a Unitarian Universalist Sunday school setting, here are some of the things I think about:

1. My teaching will be centered on activities that allow learners to be “selves in the making.” And, given my own strengths as a teacher, this means I’m going to use the arts; and knowing my limitations as a teacher, I’m going to do best with telling stories (I could see other people using dance, drama, etc., but those are not in my skill set). [This point inspired by Maxine Greene.]

2. My learners are going to be at various points in their development. I would love to be able to do some kind of formal pre-assessment, but that’s not realixtic in the context of an hour-long Sunday school session. Therefore, I’ll have to be a flexible teacher, willing to adjust my lesson plan to accommodate those who turn out to know very little, as well as those those who already know a lot. [See Bob Pazmino’s chapters on “Sociological Foundations” and “Curricular Foundations.”]

3. The educational goal of teaching about white supremacy is a BIG task. Since I have to be realistic about what can be taught (and learned) in a given limited time, I’m going to set realistic — and probably modest modest — educational objectives for one teach-in session. But for the long term, I will also continue the liberative educational praxis I’m already using and committed to. [See bell hooks about the realities of teaching.]

4. Anybody who has taught knows that teachers have to regulate the emotional temperature of a class. The phrase “white supremacy” will obviously generate strong emotions in many people; in fact, that’s the whole point of using that phrase. But I don’t want to limit my educational objective to merely eliciting emotions of shame, anger, guilt, and/or hatred, because from experience I know that too much of those emotions can stop the learning process temporarily (e.g., white people can shut down due to shame, non-white people can shut down due to anger, etc.). So I’ll need to balance how these emotions are elicited in the short-term, against a long-term goal of liberative educational praxis.

5. Oversimplification is always a temptation in teaching, and I think it’s a particularly strong temptation when teaching about white supremacy. To avoid oversimplification, I’m going to take inspiration from Marcia Chatelaine’s advice on teaching about Ferguson: use intersectionality. Intersectionality asks: how are different oppressions linked? (I suspect this will be an especially useful approach for adult Unitarian Universalists, because so many of them are already doing significant work and learning in sexism, classism, ablism, homophobia, etc.; thus intersectionality can connect what they’ve already accomplished and learned about to the topic of white supremacy.) [This point inspired by Marcia Chatelaine.]

6. Chatelaine also suggests: focus on an intellectual discipline or subject area you know well, and delve into that. The intellectual disciplines where I have some level of professional knowledge and expertise — philosophy, liberal theology, religious education — aren’t particularly well suited to teaching children and teens about white supremacy. So I tried to think of a subject area where, although I don’t have professional expertise, I have enough knowledge that I could teach something to children — and I thought of environmental justice, a topic I have already taught to children and teens, and a topic that lies at the center of social justice concern in our congregation.

———

The above are some preliminary considerations and practical ideas for implementing a one-shot “teach-in” on white supremacy. Note that what I am proposing does not necessarily conform to the teach-in called for by Black Lives of UUU. I’m specifically addressing the educational considerations of teaching young people in a Sunday school setting; Black Lives of UU has issued a broader call to include this topic in worship services, Sunday morning Forum, etc.

Furthermore, my practical ideas grow out my own congregation, here in the very specific cultural context of the Bay Area — a region where Cesar Chavez started his career, a region where Chinese immigrants at times lived in virtual slavery, a region where Japanese Americans were illegally (and immorally) interned during the Second World War, a region where one police force (Oakland P.D.) was under federal control because of racial prejudice. I could also mention Oscar Grant. I could also mention to overt sexism and racism of Silicon Valley companies like Facebook, Google, Apple, etc., and of start-up culture, and of Silicon Valley venture capital firms. In terms of environmental justice, I might consider why it is that East Palo Alto, a historically black city, doesn’t have enough water supply to support the kind of development that could bring more jobs (and could also bring more gentrification that might drive out people of color). Bay Area racial history is complex, and your area will differ.