This afternoon, we went for a walk at Purissima Creek Redwoods Open Space Preserve in the Santa Cruz Mountains southwest of San Mateo. It was a stunning afternoon, warm but not too hot, with fog beginning to roll in up the canyons from the ocean.

As we hiked down into the preserve, we kept hearing a hawk screaming somewhere in the distance, but we never saw it. And then when we were hiking back up to the parking lot, there it was overhead: an accipter flying over the ridge we were on, then turning and riding the breeze coming up the canyon to our right. And what kind of accipter was it, a Cooper’s Hawk or a Sharp-shinned Hawk? I’d say it was perhaps a little larger, the neck a little longer, the tail a little more rounded, the wingbeats a little more deliberate: probably a Cooper’s Hawk, but I’m not good enough at field identification to be sure. It wheeled around, high above the canyon floor but at eye level for us; a couple of Band-tailed Pigeons came over the ridge, saw the accipter, and quickly ducked into the trees below us. Then the fog rolled up the canyon, and it was gone.

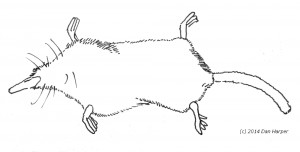

As we continued up the trail, Carol got about a hundred feet in front of me. Suddenly we both froze: walking the trail well up the hill in front of us was a dog-sized canid: a Gray Fox, its long tail behind it, its head turning from side to side, giving us a flash of the rufous fur up the side of the neck. It didn’t seem to notice us; it was busy watching the undergrowth on either side of the trail, and at least once it pounced at something.

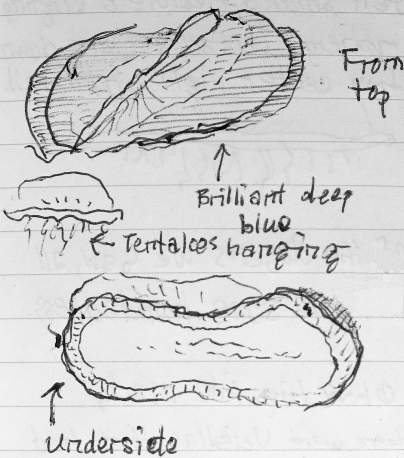

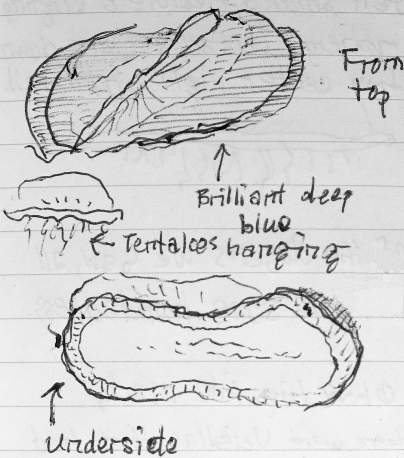

We got back to the car a little after seven, and decided to go down to the beach to eat dinner. It was a beautiful foggy evening, and we walked along past Heerman’s and California Gulls, but the real attraction of the beach was the Velella velellas. When I was reading up on this species last night, I found a Web page by Dr. David Cowles that gave a possible reason why so many Velella velellas have washed up on northern California beaches:

“The angled sail makes it sail at 45 degrees from the prevailing wind. Some have a sail angled to the left, others to the right. Off California the right-angled form prevails, and these remain offshore in the prevailing northerly winds. Strong southerly or westerly winds, however, may bring huge aggregations ashore.”

We walked down the beach, making an unscientific survey: of the dozens of individuals we saw — ranging in size from less than two inches long to one that was as long as my notebook or approximately four inches (10 cm) long — all the sails had the same handedness (according to Dr. Cowles’ terminology, right-angled sails). Here’s a sketch from my notebook:

I picked one up by its sail to look at the tentacles hanging down underneath. The velellas, like the fox and accipter, are predators, feeding on smaller organisms with their dangling tentacles. The tentacles seemed to descend from the central oval, and were of varying lengths. The sail itself felt smooth, flexible, and slightly rubbery; I dropped it back into the waves after I had looked at it.

Three very different predators — but each one a fabulously beautiful organism.