This week I’ve been posting images of deities. But what is a deity, anyway?

Here in the United States, popular culture has been heavily influenced by Protestant Christian culture, and so when we are asked to define a deity, we default to the concept of a monotheistic transcendent deity. If we have to draw a picture of this deity, we might either draw a picture of a man with a white beard sitting on a cloud, or say that this deity is transcendent and can’t be pictured.

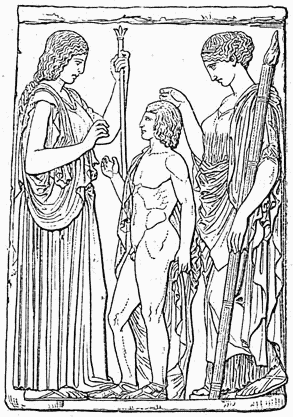

However, most of the human race, for most of human history, has had a far more complex and nuanced understanding of deities. In our own Western cultural tradition, which extends back to the civilizations of Rome, Greece, and the ancient Near East more generally, we can find a great diversity of deities. Here’s a list of some of the categories of deity we can identify in the Western religious traditions:

• a single transcendent deity, e.g., the transcendent god of Xenophanes and other early Greek philosophers; God for some Jews; God the Father for some Christian sects

• a most powerful deity among other deities, e.g., Zeus in ancient Greece

• greater deities, e.g., the more powerful ancient Egyptian deities such as Horus, Osiris, and Ra

• lesser deities, e.g., the Titans in ancient Greece

• local deities, e.g., river gods, deities of a grove or forest, etc.

• household deities, e.g., the household gods of ancient Rome, etc.

• deified humans, e.g., the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh, Roman emperors deified after death, etc. (some might argue that the Virgin Mary of some Christian sects fits into this category)

• humans that are more than mortal but slightly less than gods, e.g., Herakles for the ancient Greeks, Jesus for the Christian followers of Arius, etc.

• humans with special powers who are worthy of veneration, e.g., canonized saints, sports figures and celebrities, etc.

• abstract concepts as deities, e.g., god as the unmoved mover in Aristotle, scientific method, financial success, etc.

These are just the first examples from the Western religious traditions that come to my mind. Then we can add in all the deities which are current in our increasingly multicultural world, such as the vast hierarchy of Hindu deities, the several Buddhas (who may appear as humans with special powers, but who may also appear as transcendent deities), ancestors who are venerated (as in some African traditions), deities as part of nature or tied to natural places (as with some Navajo deities), etc., etc.

I don’t believe we should accept without question the U.S. Protestant Christian definition of deity as a single transcendent god in whom one either believes or doesn’t believe. Humans in the U.S. today venerate a variety of deities, many of which look nothing like the U.S. Protestant transcendent God. And that veneration can take a variety of forms, from overt public worship to more covert forms of veneration. Given that, don’t you think that there is a lot more religion in the U.S. today than is captured by polls which ask whether people believe in “God” and attend “church”?

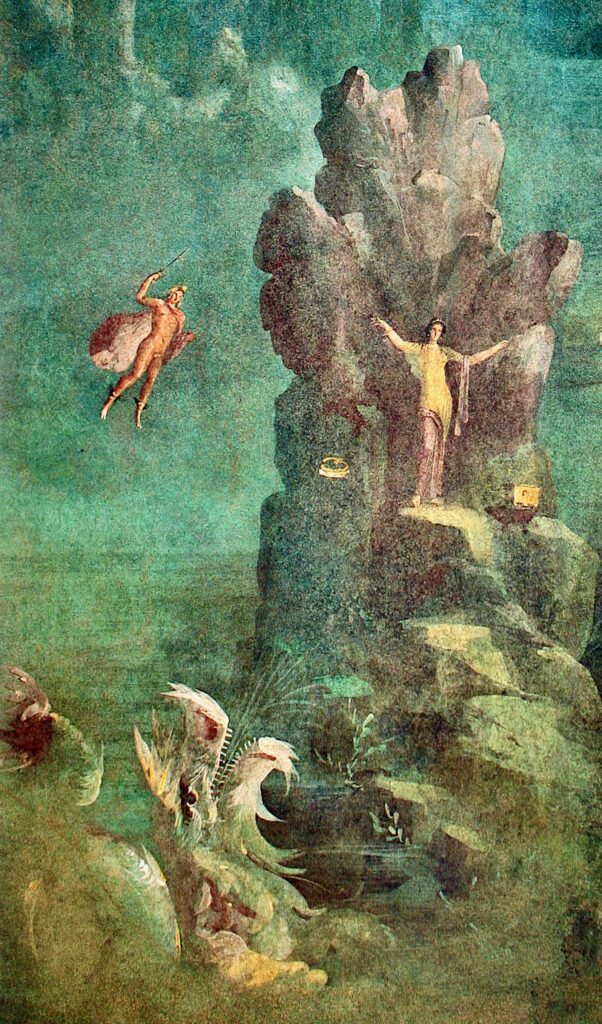

When we chose stories for this course, both of us placed the Medusa story at the top of our lists. What makes Medusa such a fascinating figure? The face of Medusa contains great power: the power to freeze others into stone. On the other hand, we considered Medusa’s killer, Perseus, to be little better than a bully, a strong-arm man who coerces others into doing what he wants through violence or the threat of violence. So the story of Medusa can lead to interesting explorations of power, and the use of power.

When we chose stories for this course, both of us placed the Medusa story at the top of our lists. What makes Medusa such a fascinating figure? The face of Medusa contains great power: the power to freeze others into stone. On the other hand, we considered Medusa’s killer, Perseus, to be little better than a bully, a strong-arm man who coerces others into doing what he wants through violence or the threat of violence. So the story of Medusa can lead to interesting explorations of power, and the use of power.