If your congregation is going to webcast your worship services, you obviously have to be careful of copyright issues. Music, especially, can cause problems: those who hold rights to music can be especially aggressive at enforcing their copyright.

This is further complicated by the fact that more than one person or entity may hold the copyright to a piece of music you wish to webcast, e.g., there may be one copyright on the music and another copyright on the arrangement, and still a third copyright on the lyrics.

Furthermore, you can’t trust the attributions in hymnals. For example, “How Can I Keep from Singing” is widely credited as an old Quaker hymn when it was composed by Robert Lowry in 1869; some of the arrangements published in hymnals are not by Lowry but are copyrighted; and the verse beginning “When tyrants tremble sick, with fear” is attributed to “Traditional” when it is copyright 1950 by Doris Plenn.

And it’s not just webcasts that cause copyright problems. By law, you cannot photocopy any copyrighted tunes, texts, or arrangements (no, not even for an insert in an order of service); nor can you project them onto a screen during a worship service.

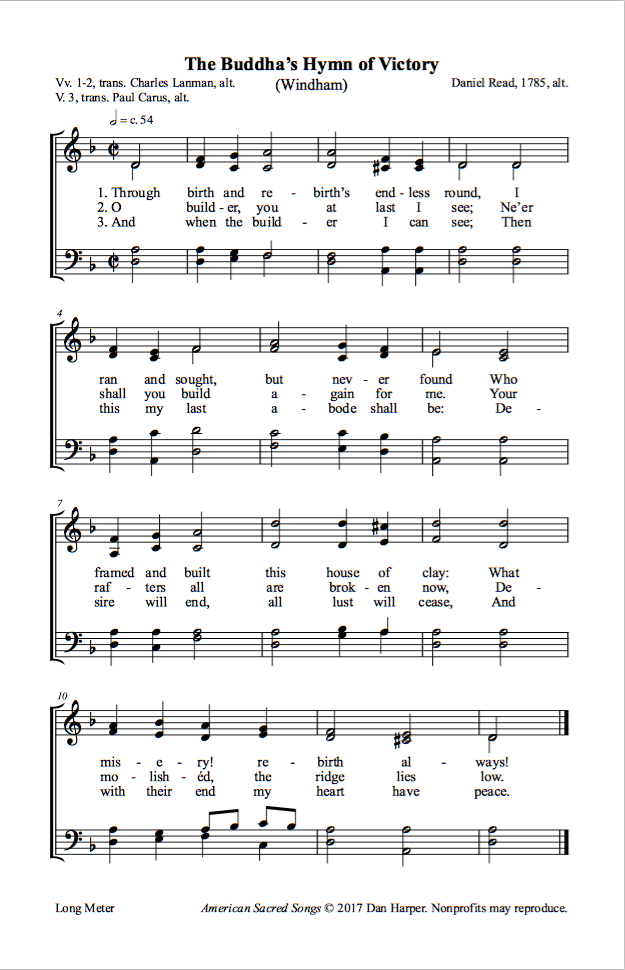

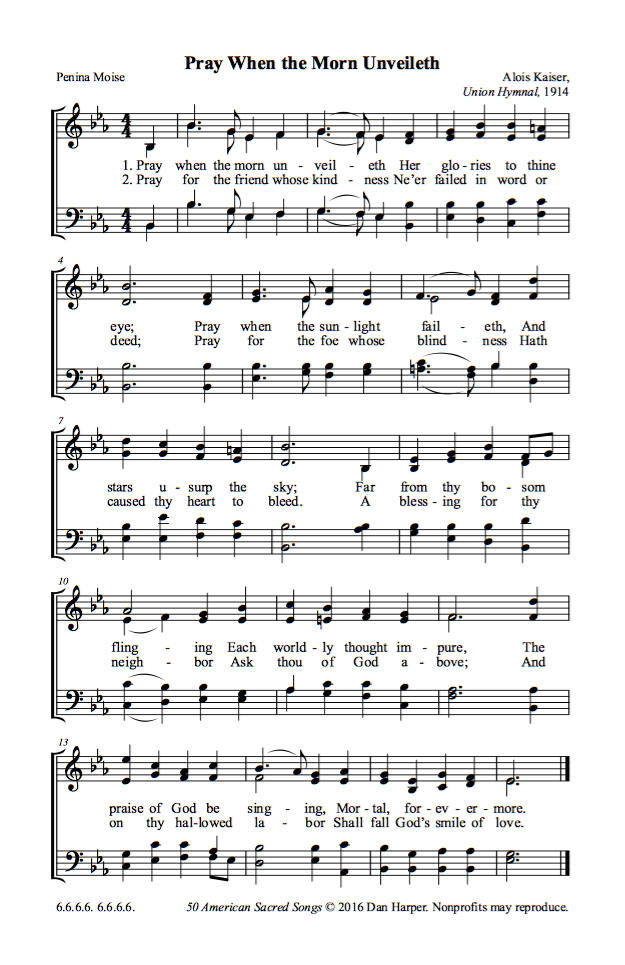

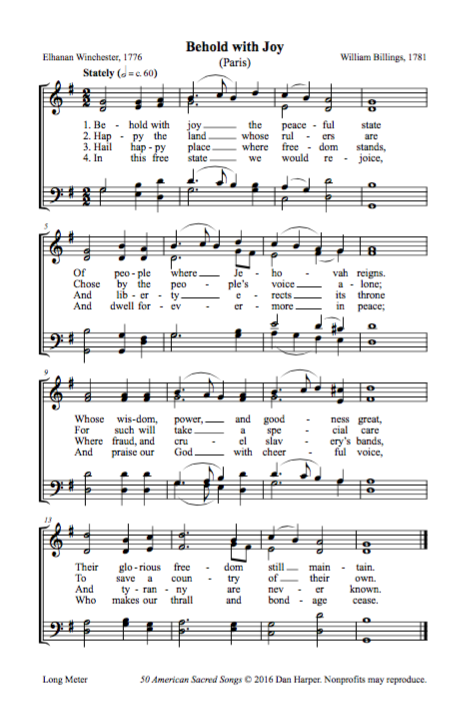

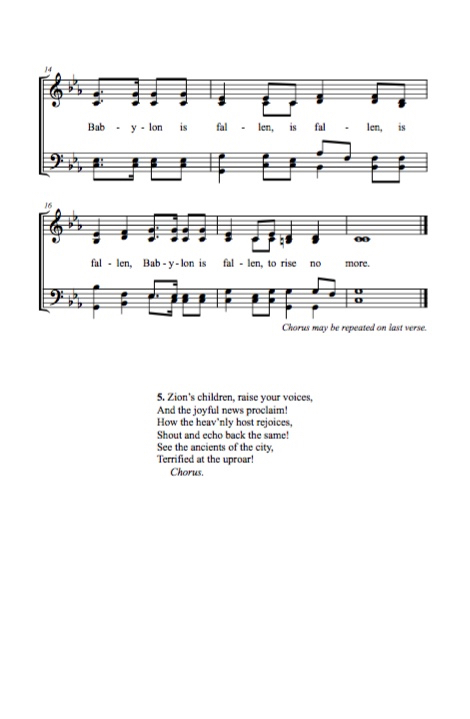

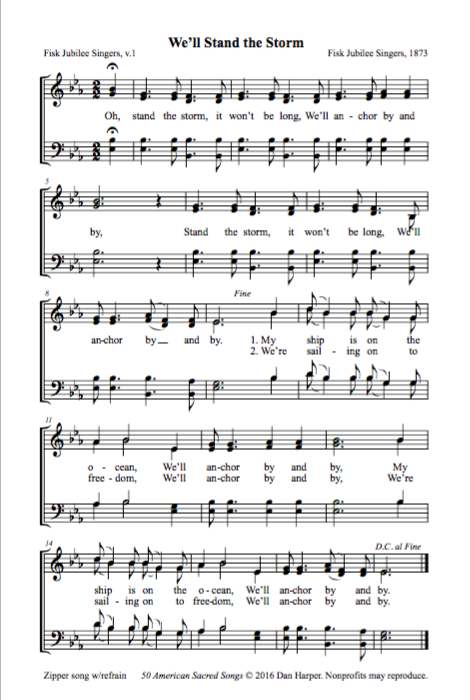

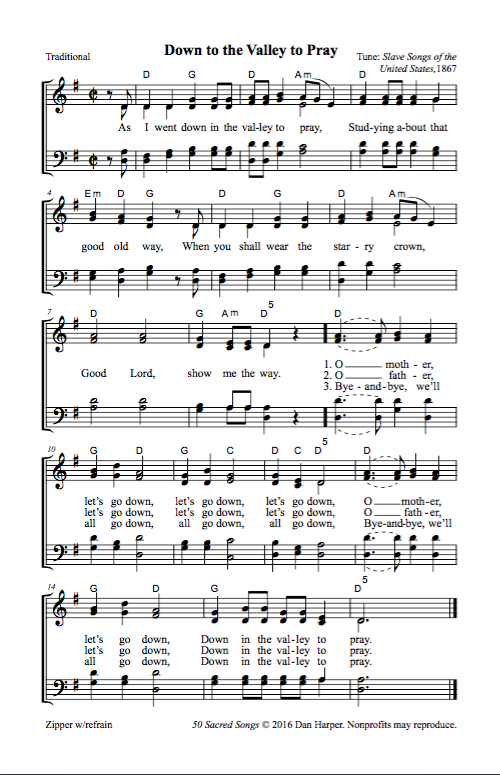

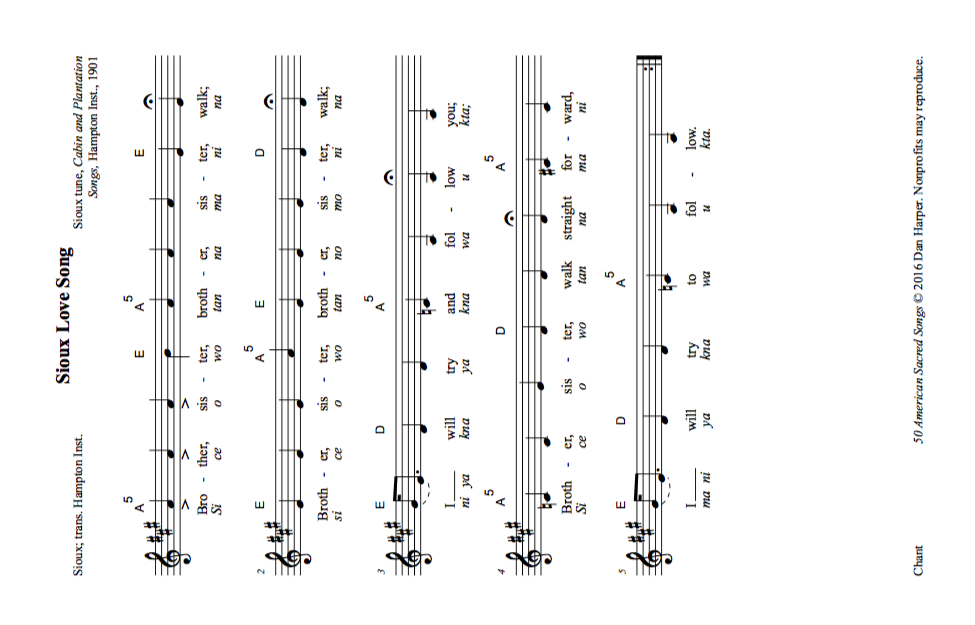

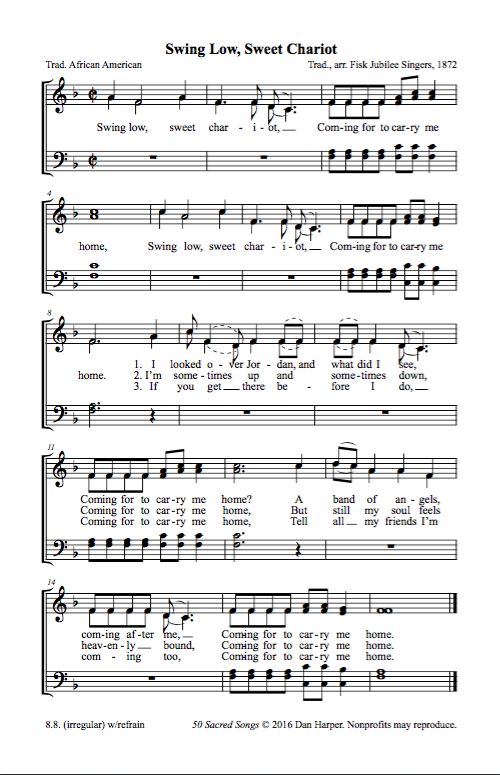

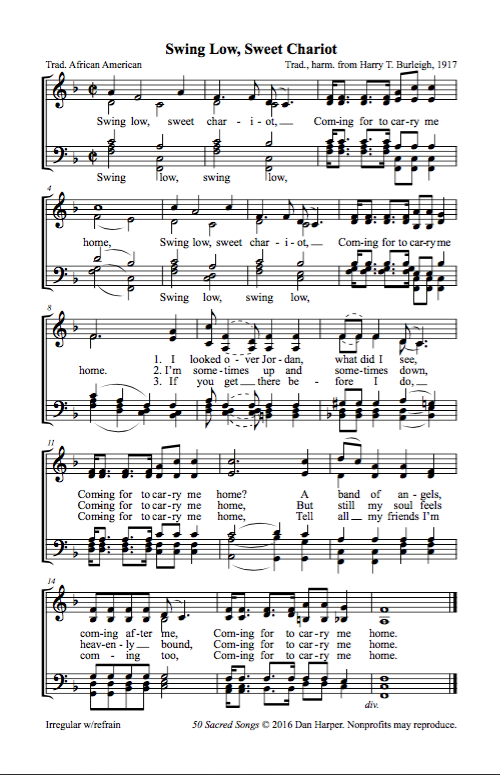

So I decided to come up with fifty or so hymns, spiritual songs, chants, etc., that can be safely used without worrying about copyright issues. The tunes, texts, and arrangements either are in the public domain — either that, or they are my arrangements of text or arrangement to which I hold copyright but which I freely permit nonprofit organizations to perform, webcast, record, or project during services.

Update, October, 2016: The project was getting out of hand, so I decided to limit it to American sacred songs, generally with American texts, tunes, and arrangements (though in a few cases I’m including a little bit of English material).

I chose to retain the copyright for two reasons: first, so someone else can’t slap their copyright on my work and profit from it (and yes, Virginia, it has been done); and second, because Creative Commons did not offer exactly the kind of license I wanted. Note that I also retain copyright of the typesetting for all public domain material.

I had another powerful motivation for producing this collection: it should be quite useful for small congregations and house churches that cannot afford to purchase expensive hymnals. A small congregation with a tiny budget can photocopy as many copies as they want; they can project these sacred songs, record them or webcast them, and the congregation can do it for little or no money.

One caveat: I did not research international copyrights. Those who live in the European Union or elsewhere may find that material that is in the public domain in the United States is still protected by copyright in their jurisdiction.

Over the next year or so, I will be posting draft versions of sacred songs from this collection. You are welcome to use them in your congregation — and if you do, I’d love to hear from you if you liked it, or if you ran into any problems.

Continue reading ““50 American Sacred Songs””