The Morton family included two generations of Palo Alto Unitarians. Katherine Kent Morton Carruth was the daughter of Howard and Jessie Wellington Morton, all of Kansas; Katherine married Prof. William Herbert Carruth of the Univ. of Kansas. Then Carruth, a nationally-known poet, took a teaching position at Stanford in 1913. Jessie and Howard followed, probably coming to live in Palo Alto after 1915 (they were not listed in a Palo Alto city directory of that year), but before the 1920 U.S. Census. As usual, it is more difficult to find biographical information for women of this era, but I was able to find a fair amount of detail about both Howard and William.

MORTON, HOWARD— He was born Oct. 24, 1836, in Plymouth, Mass., to Ichabod, a merchant, and Betsey Morton. In 1855, Howard was a student and living with his parents. In 1860, he was still living in Plymouth with his parents and two brothers, now working as a gardener. His father died in May, 1861, and Howard enlisted in the 30th Mass. Infantry on Dec. 10, 1861. He served in the Civil War in Mississippi and Alabama, and was mustered out on Sept. 23, 1865. Not long thereafter he moved to Kansas.

In 1868, Howard Morton participated in the Arickaree, or Beecher Island fight: “The battle of Beecher Island was fought on the 17th of September, 1868, and lasted nine days. Fifty-one scouts from Lincoln and Ottawa counties, Kansas, just over the line in Colorado, stood off [the Indians]” (Kansas State Hist. Soc., 1913). In a typescript passed down in his family, Howard recalled:

“Suddenly the valley and hillside were covered with mounted Indians, charging us at full speed. The little sandy island, so near, seemed our only refuge, so we hurried across, tied our horses and mules to the trees, threw ourselves in the sand, and began to fight for our lives….The Indians were all around and making it hot for us….Our horses were staggering and falling, and we were doing our best to keep the Indians on horseback from charging over us. The chiefs tried several times to lead their men onto the island, but when they came near, our fire was too hot for them, and they broke and rode around us. And so it went on through the long day and until after dark, when they drew off for the night….The fight virtually ended the first day, although they appeared early the next morning, and for several days fired at us occasionally from the hills.”

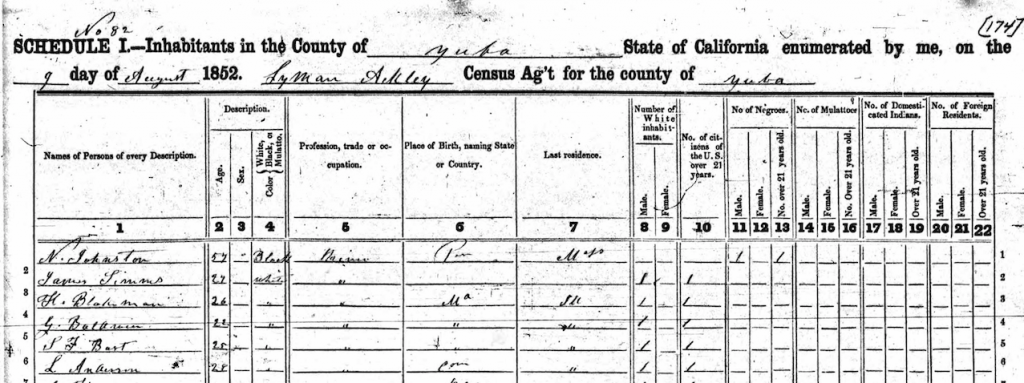

At night, they sent two men to get assistance from Fort Wallace, a hundred miles away. The embattled scouts lived for nine days on horse and mule meat, until a company of African American soldiers under the command of Col. Carpenter relieved them. Howard’s military pension record mentioned both his Civil War service, and his service with the U.S. Army Scouts.

In 1870, Howard was a farmer in Trippville, Ottawa County, Kan. Ottawa County was considered “one of the best counties in Central and Western Kansas, having a rich soil, desirable location, being most admirably watered, and possessing a good supply of timber.” He lived next door to, or near, the Wellington family. (Trippville’s name was changed to Culver in 1879, to commemorate one of the scouts who fought at the Battle of Beecher Island.)

Howard married Jessie Kent Wellington (b. June, 1854, New York) on Feb. 14, 1872, in Tescott, Kansas, the next town west of Trippville along the Saline River. They had nine children, all born in Kansas: Mary E. (b. March, 1873); Helen (b. Sept., 1874); Katherine K. Carruth (q.v.; b. April, 1876); Howard H. (b. c. 1878); Nathaniel H. (b. April, 1881); Jessie K. (b. Dec., 1883); Charlotte A. (b. Nov., 1885); Ruth W. (b. March, 1889); and Lucie W. (b. May, 1884).

In 1898, he wrote: “I have lived in Kansas thirty-two years; I have twenty old apple trees and 400 set two years ago…. My orchard is in a bottom with a north slope….” In 1900, he wrote that he did not recommend growing apricots, since his trees “never bore a full crop” and were troubled with frost and curculio.

By 1900, Howard, Jessie, and seven of their children were living in Henry and Morton Townships, Ottawa County, Kansas, where Howard was a farmer. In 1910, they all continued to live there: Howard was still a farmer, Katherine was a teacher in the primary schools, Jessie K. and Charlotte A. were college instructors, Nathaniel was a student at the university, and Jessie W., Mary E., Ruth W., and Lucy W. with no occupation listed.

By 1920, Howard, Jessie, and their daughter Mary were living in Palo Alto. They all reported their occupation as “none.”

He was a member of the Unitarian Society of Palo Alto. Rev. Elmo A. Robinson, in the 1925 annual report, reported his death: “Howard Morton, in whose memories were mingled the old time shipping scenes of Puritan Cape Cod and the stirring strifes of pioneer Kansas.”

Howard died Feb. 7, 1925.

Notes: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920 U.S. Census; 1855, 1865 Massachusetts Census; United States General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934; 18th Biennial Report of the Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas, 1913, p. 4; “My Civil War Experiences” and “Battle of Beecher Island,” typescripts from an online genealogy, www.familysearch.org/tree/person/memories/L75M-WN3, accessed 16 Aug. 2019; William G. Cutler, History of the State of Kansas, Chicago: A. T. Andreas, 1883.; Kansas Horticultural Society, The Apple…How To Grow It…, Topeka, Kansas, 1898, p. 86; Kansas Horticultural Society, The Cherry in Kansas, with a Chapter on the Apricot and Nectarine, 1900, p. 116; Veteran’s Administration pension payment cards, 1907-1933, Morton, Caroline-Mory, Henry C. (NARA Series M850, Roll 1616).

MORTON, JESSIE KENT WELLINGTON— She was born June 7, 1854, in New York, daughter of Oliver and Charlotte Wellington. By 1860, she was living in Boston with her parents and two siblings. In 1870, the family was living in Trippville (later Culver), Kansas.

She married Howard Morton (q.v.) on Feb. 14, 1872, in Tescott, Kansas. They had nine children, all born in Kansas: Mary E. (b. March, 1873); Helen (b. Sept., 1874); Katherine K. Carruth (q.v.; b. April, 1876); Howard H. (b. c. 1878); Nathaniel H. (b. April, 1881); Jessie K. (b. Dec., 1883); Charlotte A. (b. Nov., 1885); Ruth W. (b. March, 1889); and Lucie W. (b. May, 1884). Howard was a farmer.

By 1920, she and Howard were living in Palo Alto with their daughter Mary.

She was a member of the Women’s Alliance of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in the early 1920s.

After Howard’s death in 1925, she applied for a Civil War widow’s pension. She died April 9, 1936, in Palo Alto.

Her memoir, titled Adventure Ahead, was compiled and published in 1995 by her granddaughter, Jessie Morton Alford Kunkle. I have been unable to find a copy, and suspect it was issued in a small print run.

Notes: 1869, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920 U.S. Census; 1855, 1865 Massachusetts Census; United States General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934.

CARRUTH, KATHERINE KENT MORTON— A schoolteacher, she was born in April 21, 1876, in Tescott, Kansas, daughter of Howard (q.v.) and Jessie (q.v.) Morton. By 1898, her father, a farmer, had an orchard with over 400 apple trees. By 1900, she lived with her aunt and uncle, Thomas and Mary Sears, near Lawrence, Kansas, while attending school; Tom Sears and Howard Morton had homesteaded in Kansas in the spring of 1866, helping to found the town of Tescott.

Katherine hoped to be a concert pianist, and practiced 8 to 10 hours daily. However, she became a school teacher to supplement the family’s income. She was teaching in the public schools of Lawrence, Kansas, in 1909 when she became engaged to be married to William Herbert Carruth. She married Carruth on June 12, 1910, in her parents’ home in Tescott. The officiant was Rev. Frederick Marsh Bennett, minister of the Unitarian church in Lawrence. They had a daughter, Katharine (b. Dec. 2, 1911), known as Trena.

When the Carruths moved to Palo Alto, Katherine was active in the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto. She taught the “sub-primary” (i.e., kindergarten and younger) grade in the Sunday school, 1925-1926.

She was included on a list of Unitarians to contact in 1947 when a new Unitarian congregation was being formed; next to her name on this list is the notation: “too elderly to take part, is sorry.”

She continued to live in Palo Alto until about 1970, when she moved to a convalescent hospital in Santa Cruz. She died January 11, 1973, in Santa Cruz.

Notes: 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920 U.S. Census; Kansas Horticultural Society, The Apple…How To Grow It…, Topeka, Kansas, 1898, p. 86; Harrison Monell Sayre, Descendants of Deacon Ephraim Sayre, Edwards Brothers, 1942, p. 8; Obituary, Palo Alto Times, Jan. 11, 1973; Jeffersonian Gazette, Lawrence, Kansas, Dec. 8, 1909, p. 8; Graduate Magazine of the University of Kansas, June, 1910, p. 341; Salina [Kansas] Evening Journal, June 10, 1910, p. 2; Graduate Magazine of the University of Kansas, Dec., 1911, p. 114; Margaret R. O’Leary and Dennis S. O’Leary, R. D. O’Leary (1866-1936): Notes from Mount Oread, 1914-1915, Bloomington, Ind.: iUniverse, 2015, ch. 6 n.1; “Names from 1947 Project,” typescript in archives of Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto; California Death Index.

CARRUTH, WILLIAM HERBERT— A poet and a professor who taught German, writing, and comparative literature, he was born April 5, 1859, on a farm near Osawatomie, Kansas. His father was a clergyman and botanist. As a child, he “distinguished himself in the Presbyterian Sunday school by repeating without mistake an amazingly large number of Bible verses.” But he left Presbyterianism for Unitarianism early in life.

William graduated from the University of Kansas in 1880. He married Frances Schlegel of Boston in June, 1882, and they had a daughter, Constance.

William received his A.M. from Harvard in 1889, and his Ph.D. in 1893. He also studied at Berlin and Munich. He was professor of German at the University of Kansas from 1880 till he went to Stanford. Frances was professor of modern languages at Univ. of Kansas until her death in 1908.

He was also involved in the eugenics movement. The opening paragraph of an address he gave at the University of Kansas on May 8, 1913, shows that he offered the usual rationale for eugenics:

“Long before the alarmed cry of Theodore Roosevelt against ‘race suicide’ called public attention in America to this subject, thoughtful students had begun to point out appalling tendencies toward degeneracy in the breeding of civilised [sic] nations. In so far as the warning against ‘race suicide’ was merely an indiscriminate appeal for more children, a revival of the Biblical admonition to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ without forethought and safeguards, it was only a blind summons to more ‘race suicide.’ What the world needs is not indiscriminately more children, but more children from the best stock and fewer from the worst stock.”

William was an active Unitarian, both locally and nationally. He was a member of the Unitarian church in Lawrence, Kansas. He served as a director of the American Unitarian Assoc. from 1906 to 1909; subsequently he served as the national president of the Unitarian Laymen’s League. In the early 1920s, he was a trustee of the Pacific Unitarian Conference, and a trustee of the Pacific Unitarian School for Ministry.

After Frances died, William married Katharine Kent Morton (q.v.) on June 12, 1910. They had a daughter, Katharine (b. Dec. 2, 1911). William accepted a position at Stanford in 1913, and the family moved to California.

During his lifetime, William was a well-known poet. His best-known poem, widely anthologized in its day, was “Each in His Own Tongue,” first published in 1888 in The New England Magazine. This was the title poem of his 1908 book Each in His Own Tongue. At Stanford, he was professor of comparative literature, and also taught classes in writing poetry. In 1923, John Steinbeck was in his writing class. Edward Strong, who was in the same class, recalled:

“We … competed against each other in our writing of poetry to see who would receive the better grade from Professor Carruth. When we got our grades, John got an A, and I received a B+. I said to John, ‘Now look, you’ve read my poetry and I’ve read your poetry. Do you think your poetry was any better than mine?’ He said no. Then I said, ‘Well, can you explain, then, why you have received an A from Professor Carruth and I’ve received only a B+?’ He said, ‘Because you didn’t dwell in your poetry on the theme that would win an A from Professor Carruth.’ I said, ‘Theme?’ He said, ‘Professor Carruth has been strong on one theme. Some call it evolution, and some call it God [a line from Carruth’s best-known poem]. I wrote about God. I got the A.’”

William was an active member of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, serving most notably as president of the Board of Trustees. He also preached there upon occasion.

Towards the end of his life, he taught a course on “Religion of the Great Poets” at the Pacific Unitarian School of Religion. One of his students there, Julia Budlong, recalled him as being “tall… and sinewy, and dry-looking, like his humor,— inclined to be absent-minded and inattentive.” Budlong also recalled him driving her in his open automobile on a wild ride from the Unitarian church to his house on Stanford’s campus, with the speedometer at fifty miles an hour the whole way.

He died Dec. 15, 1924.

Notes: George W. Martin, ed., Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1911-1912, Topeka, Kansas: State Printing Office, 1912, p. 87 n.; National Cyclopedia of American Biography, New York: James T. White, 1910; Eugenics: Twelve University Lectures, New York: Dodd, Mead, & Co., 1914, p. 272; Edward W. Strong, “Philosopher, Professor, and Berkeley Chancellor, 1961-1965,” 1988 interview with Harriet Nathan, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1992, www.oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt8f59n9j3&query=&brand=oac4 accessed Oct. 12, 2013; Graduate Magazine of the University of Kansas, 1913, p. 14; Graduate Magazine of the University of Kansas, Nov., 1906, p. 66; Stanford University, Annual Report of the President for the Thirty-third Academic Year, Stanford Univ., 1925; Graduate Magazine of the University of Kansas, Dec., 1911, p. 114; Pacific Unitarian, vol. 35, no. 3, March, 1925, pp. 44-46.