What words do you use to say grace at Thanksgiving? Do you use a traditional grace, or are you looking for an alternative blessing for you Thanksgiving dinner? As Unitarian Universalists (UUs), we have lots of options when it comes to saying grace at Thanksgiving.

When I was a UU child, we often had Thanksgiving dinner with my mother’s twin and her family. Our cousins were all older than my sisters and I, and we looked up to them. Both our families were UU families, and one year at Thanksgiving our eldest cousin said she was going to say grace before dinner, using a grace she had heard in her UU congregation’s youth group. My mother and father and aunt and uncle all liked the idea, and told her to go ahead. She had us all join hands, and then said, “Rub-a-dub-dub, thanks for the grub, yay God!” I’m not sure the adults at the table were particularly impressed, but my sisters and I were definitely impressed.

Even if you never say grace at any other time of the year, Thanksgiving is a good time to pause before eating, and give thanks for your food. The challenge for us religious liberals is coming up with pleasing ways to give thanks that don’t rely on traditional Christian theology. My UU friend Craig Schwalenberg adapted this grace from his Lutheran childhood:

Cherished family, friends, and guests,

Let this food to us be blessed.

Bless those people who made this food.

May it feed our work for good.

Another friend of mine, Emma Mitchell, grew up as a Unitarian Universalist, and says her family used to say this for grace (and children got to choose whether to refer to God as “her” or “him”):

God is great, God is good,

Let us thank (her) (him) for our food.

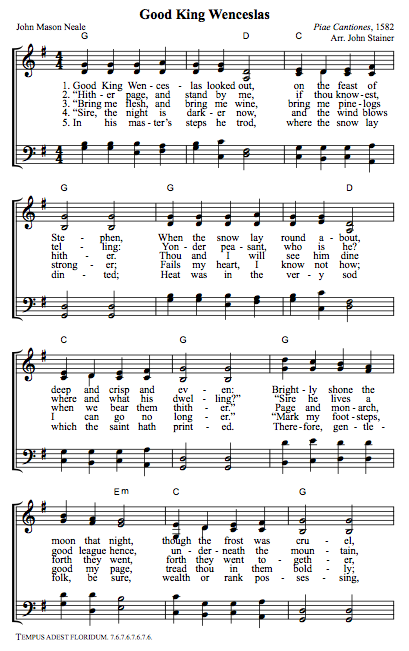

I wrote the following grace to remind us of the interdependent web of existence, including farmworkers and the wider ecosystem (there’s a tune that goes with this, and it’s online here):

Praise workers laboring hard in their fields,

May sun and moon increase their yields,

May the soil be blessed by falling silver rains,

As we offer thanks to Mother Earth again.

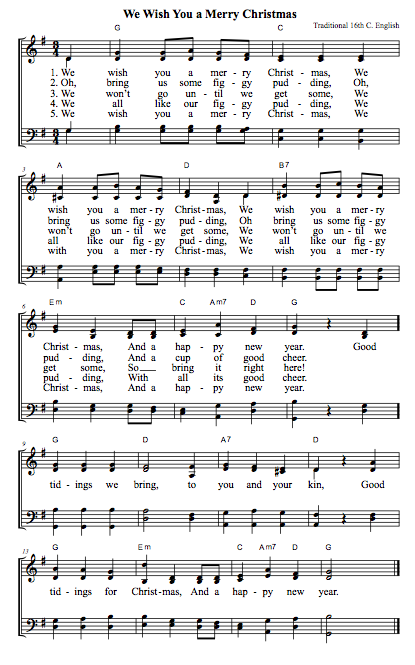

What’s your favorite alternative Thanksgiving blessing? UUCPA member Kris Geering writes: “For the pagan-friendly folks, I like this grace (there’s a tune you can sing it to, but it’s good as is):”

Give thanks to the Mother Goddess,

Give thanks to the Father Sun.

Give thanks to the plants and the flowers in the garden

Where the Father and the Mother are one.

Rev. Amy Zucker-Morgenstern, our senior minister at UUCPA, sent in the following grace:

Our family grace is to hold hands and say “Thank you for the food,” in as many languages as are known by people at the table. Common variations include thanks to the farmworkers, truckers, people who invented whatever cuisine it is, Mommy or Mama for cooking, etc.

What about you? what’s your favorite non-traditional Thanksgiving grace?

Cross-posted here.