I’ve just finished reading Mark Chavez’s book American Religion: Contemporary Trends (Princeton University, 2011), which is well-written and blessedly brief. Chavez’s major conclusion: religious participation in U.S. congregations is either stable or declining (it’s not clear which), but it is definitely not increasing.

Towards the end of the book, Chavez brings up a reason why we should be concerned about declining participation in U.S. religion. Chavez writes:

If half of all the social capital in America — meaning half of all the face-to-face associational activity, personal philanthropy, and volunteering — happens through religious institutions, the vitality of those institutions influences more than American religious life. Weaker religious institutions would mean a different kind of American civic life.

Of course we should not be surprised to learn that in this time of civic disengagement in the U.S., involvement in congregations is at best stable, and at worst in decline — that would fit in with the wider sociological trend. Nevertheless, we should worry that congregational participation is at best stable. James Luther Adams, the great mid-twentieth century Unitarian Universalist theologian, used his experiences in Nazi Germany to demonstrate that weakened voluntary associations led to weakened democracy, allowing totalitarianism to establish a foothold.

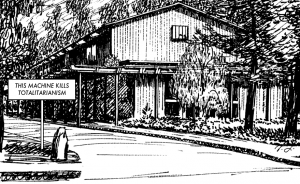

If U.S. participation in religious congregations declines, that means half of all participation in voluntary associations declines — which, depending on your political persuasion, might be something to worry about. On the other hand, if you want another reason to justify your participation in a local congregation, you could say that going to Sunday services helps fight totalitarianism. Woody Guthrie’s guitar had a sticker on it that proclaimed “This machine kills fascists” — maybe we should place signs out in front of our congregations that say “This machine kills totalitarianism.”

Proposed sign for the front of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (click for a larger image)