Another story for liberal religious kids. Originally written c. 2000 for First Parish in Lexington, Mass. I dusted off this old story and fixed it up a little because my current congregation’s Sunday school will be learning about P. T. Barnum this year. This story comes from his 1872 autobiography, Struggles and Triumphs.

He was the greatest showman in America! He was a man who was known and loved everywhere, the most famous person in the United States in the nineteenth century! He was the man who created “the greatest show on earth”! His name was Phineas Taylor Barnum.

P. T. Barnum was a showman, the greatest showman of all time, a man who put on shows of strange and wonderful things in his giant Museum in New York City. He exhibited the very first live hippopotamus ever seen in North America. His museum was known for its amazing and incredible animals. He even exhibited the amazing Feejee Mermaid. (Well, actually he later admitted that the Feejee Mermaid was a fake that had been glued together.)

He was a showman, but more than that he was an expert at making money. He had a two-part secret for making money. First, give the public good value. Second, get all the free advertising that you can. Here’s an example of how Barnum gave good value, and got free advertising for his fabulous American Museum….

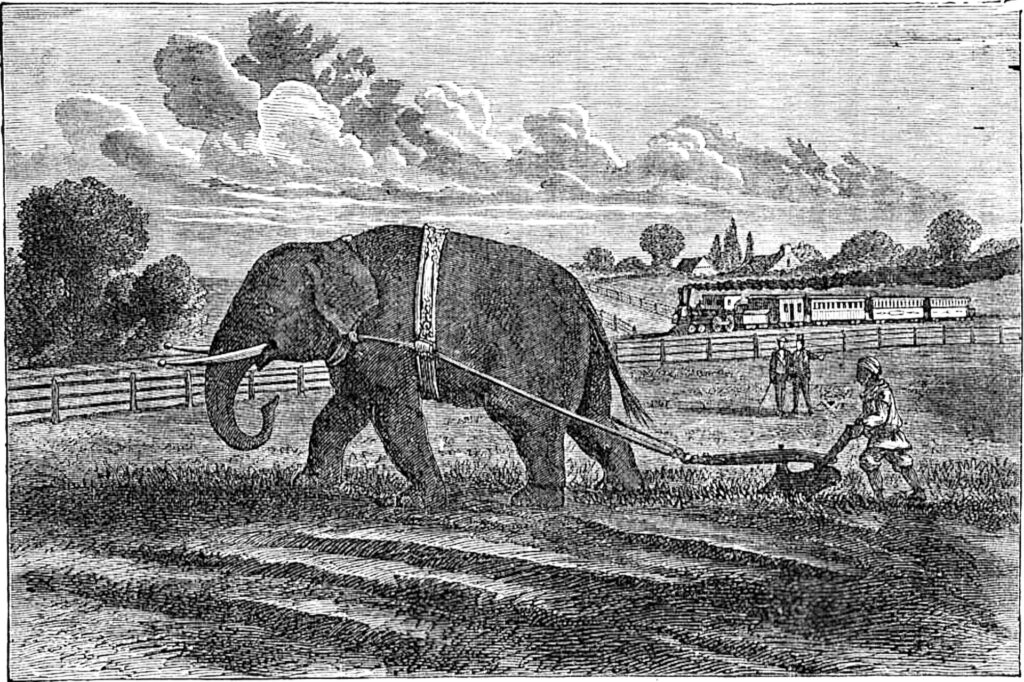

P. T. Barnum brought thirteen elephants Asia to North America. He exhibited them in New York and all across the North American continent. After four years, he sold all but one. He kept that one for his farm in Connecticut. He figured out a way that the elephant could draw a plow. Then he hired a man to use the elephant to plow a tiny corner of Barnum’s farm, which just happened to be right next to the main line of the New York and New Haven Railroad.

P. T. Barnum gave this man a time-table for the railroad. Every time a passenger train was due to pass by, the man made sure the elephant was busily engaged in drawing the plow, right where all the passengers could see.

Hundreds of people each day rode the train past Barnum’s elephant. Everyone who saw it was amazed and astonished. Barnum was using an elephant to draw a plow! Reporters from all the New York newspapers came to write stories on this amazing spectacle. People wrote letters to Barnum from far and wide, asking his advice on how they, too, might use an elephant to draw a plow on their farms.

When Barnum responded to these letters, he always wrote: “Now this is strictly confidential, but for goodness sake don’t even think of getting an elephant. They eat far too much hay and you would lose money. I’m just doing it to draw attention to my museum in New York.”

Pictures of Barnum’s elephant pulling the plow began to appear in newspapers all across the United States, and even overseas in Europe. People came out to Connecticut on purpose just to see Barnum’s elephant at work. They would say, “Why look at that! That’s a real elephant drawing that plow! If Barnum can use an elephant on his farm, he must have all kinds of animals at his Museum. Guess I’ll go to Barnum’s Museum next time I’m in New York city.”

One day, an old farmer friend of Barnum’s came to visit. This farmer wanted to see the elephant at work. By this time, that six acre plot of land beside the railroad had been plowed over about sixty times. The farmer watched the elephant work for a while, and then he turned to Barnum and said, “My team of oxen could pull harder than that elephant any day.”

“Oh, I think that elephant can draw better than your oxen,” said Barnum.

“I don’t want to doubt your word,” said his farmer friend, “but tell me how that elephant can draw better than my oxen.”

Barnum replied, “That elephant is drawing the attention of twenty million people to Barnum’s Museum.”

P. T. Barnum later became famous for his circus, but not many people know that he was also a Universalist. He’s one of my favorite Unitarian Universalists, precisely because he wasn’t perfect. He didn’t always tell the truth, but at least he later admitted when he tried to fool people. He made too much money, but he made sure to give lots of his money away to help other people. He gave money to poor people, and he gave money to help people stop drinking, and he built parks that everyone could use, and he gave lots of money to his Universalist church. I like P. T. Barnum because I know I’m not perfect. But even though I make mistakes, I can follow Barnum’s example and help make the world a better place.