Revised version, 15 April 2016

Documenting a Local Faith Community, pt. 1

Our local faith community, the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA), is a congregation affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), the merger of the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Church of America. Both the Unitarians and the Universalists started out by rejecting standard Christian doctrines and creeds, and by the late nineteenth century they had become “post-Christian” religious groups. (7) Today, most Christians would not consider UUCPA to be a Christian church: we affirm neither the Nicene Creed, nor Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior; the majority of the congregation are atheists; some of our congregants assert multiple religious identities including non-Christian religious identities such as humanism, Buddhism, etc. Yet to non-Christians, we look like Christians: we meet on Sunday mornings; our religious services resemble standard U.S. Protestant Christian worship services; and our official name is the “Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto.” So the most convenient term for us remains “post-Christian.”

Most Sunday mornings, you will see me standing outside the door to the Main Hall on the campus of UUCPA, greeting families and individuals as they come up the covered walkway from the parking lot and the bike racks, or in the other direction from the front garden. On one particular Sunday morning, Reva, age 12, and her father wave at me as they walk up from their electric car. Reva is looking forward to “Pi Day,” March 14; she has memorized pi to over a hundred digits. When I comment that Pi Day is less fun this year than last, because last year was 3/14/15, Reva’s father points out that if you round up pi to four digits after the decimal point, you have 3.1416. Reva’s family is committed to fighting climate change, and they purchased an electric Nissan Leaf soon after the car came on the market. This family is typical of many Silicon Valley families in the congregation: they celebrate Pi Day, the children are well-versed in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) learning, and they all show their commitment to the global environmental crisis by embracing new technological solutions.

Inside the Main Hall, the senior minister, Amy Morgenstern, has started the service. Three sixth grade girls, Zoe, Becky, and Eva, say “Hi!” to me as they race through the door to take up their usual places in the back corner of the Main Hall. All our children and teens spend the first fifteen minutes of every service in the Main Hall before they go off to Sunday school. While some children prefer to sit with their parents and pay attention to the service, these sixth graders sit quietly in a corner and pay attention to each other.

I finish greeting latecomers, slipping into the Main Hall as Beverly, the lay worship associate, reads this week’s centering words. “With our centering words each week,” says Beverly, “we draw on the many sources of our living tradition.” She reads a short excerpt from a contemporary poem; then she rings a bell, inviting everyone “to follow the sound of the bell into silence.” I’m standing next to where Zoe, Becky, and Maria are sitting. They are still interacting through gestures and facial expressions, and though they are not making any noise I would not say that they are spiritually silent; and I’m pretty sure they didn’t heard the centering words Beverly just read.

Everybody stands to sing the first hymn together. Most of the children know this hymn by heart, a contemporary spiritual song called “Come Sing a Song with Me.” One fifth grader stands on her chair, holding on to a parent, leaning her head back, her whole body involved in singing this, her favorite song. At the beginning of the last verse, I open the side door to the Main Hall, and forty or so children run pell-mell out the door and across the patio towards their Sunday school classrooms. Two generations ago, the children going off to Sunday school would have been almost entirely white, reflecting both a deep racial divide in American religious life, and the fact that the city of Palo Alto was over 90% white. Today, the city of Palo Alto is about 65% white while the surrounding county is now white-minority; nearly a third of the population of Palo Alto is foreign-born. (8) On this Sunday, the children going off to Sunday school are about 75% white; the non-white children at UUCPA are mostly of East and South Asian descent, but also of African descent, Latino/a, Middle Eastern, etc.

While the children race each other to see who will be first in their classrooms (not necessarily because they love class; in some classrooms there are a few couches, and the first ones in the classroom will get a seat on a couch), I reflect on the invisible economic differences between them. The median household income in Santa Clara County is close to $95,000, the highest median household income of any county in the U.S.; at the same time only 13.3% of households have an income in the range of $50,000-75,000, showing that “the middle class is being hollowed out.” (9) Many of the families who are affiliated with UUCPA have annual household incomes well over $100,000, but others are struggling to get by, especially given the exceedingly high cost of housing in Silicon Valley. (10) The majority of the regular attendees of UUCPA have incomes that place them in the middle class and upper middle class, but some regular attendees receive federal assistance for rental housing (so-called “Section 8 housing”). (11)

When I arrive in the classroom, Lorraine, my co-teacher for the sixth grade Ecojustice class, is already there. Of the seven children present today, five are white and two are non-white; six are girls and one is a boy. I take attendance while Lorraine asks one of the children to light a candle in a chalice (a flaming chalice is a common symbol for Unitarian Universalism). The children all say our usual opening words together: “We light this chalice in honor of Unitarian Universalism, the church of the open minds, helping hands, and loving hearts,” (12) and we all do the hand motions that go with each phrase. Next we everyone gets to tell about one good thing and one bad thing that happened to them in the past week; Becky is the only one who doesn’t participate in this; she never participates except when there are only one or two children in class.

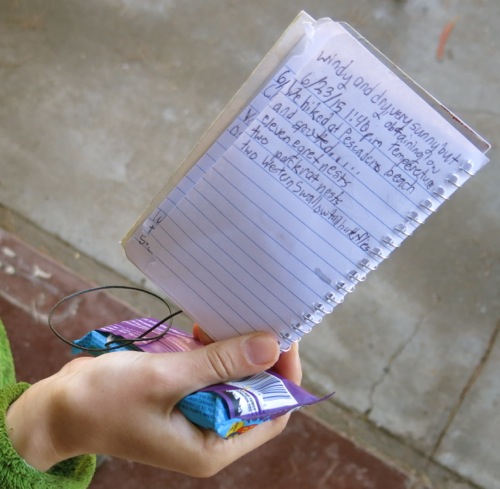

Today we’re going to work on making nesting boxes for the Violet-green Swallows that fly over the creek that flows along the edge of the church campus. But first the children want to check on their worm composter and their “recycled container garden” which they made from a worn-out automobile tire and discarded wood pallets. On our way to the composter and the garden, we stop at the church kitchen to pick up some vegetable scraps that the worms would like. As the children dump the scraps into the composter, Lorraine reminds them that we should add dry plant waste to the composter. Two of the children drag over a large yard waste bin and add handfuls of dead leaves along with the vegetable scraps. Aiofe reaches into the composter and finds some worms, which she holds in her hand to show the others. Next we check the container garden, made of a discarded tire. (13) The squirrels have dug holes in the dirt and disrupted the seeds we planted, so I promise to make a wire cage to keep out the squirrels.

Notes:

(7) Historian of religion Gary Dorrien writes that “the implicitly post-Christian religious humanism” of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Theodore Parker, two theological giants of mid-nineteenth century Unitarianism, had “reconfigured” the Unitarians by the late nineteenth century into a post-Christian denomination (The Making of American Liberal Theology, 1805-1900 [Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001], pp. 105-109). The Universalists became post-Christian somewhat later, but were post-Christian by the time of the merger with Unitarians in 1961.

(8) The U.S. Census Bureau provides the following data for the city of Palo Alto on “Race and Hispanic Origin” from the 2010 Census (as of April 1, 2020): White alone, 64.2%; Black of African American alone, 1.9%; American Indian and Alaska Native alone, 0.2%; Asian alone, 27.1%; Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone, 0.2%; Two or More Races, 4.2%; Hispanic or Latino, 6.2%; White alone, not Hispanic or Latino, 60.6%. 32.3% of the population in Palo Alto in 2010 was foreign-born. United States Census Bureau, QuickFacts, Palo Alto city, California, accessed March 26, 2016: link.

The immediate neighborhood of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA) is slightly more diverse than the city as a whole. The racial and ethnic composition of census tract 510803, where UUCPA is located: 59% White, 1% Black, 5% Hispanic, 32% Asian, 2% Other. Neighboring census tract 5107 is white minority, at 47% white. “Mapping America: Every City, Every Block,” New York Times, accessed March 26, 2016: link.

(9) Data are from a 2014 study prepared by IHS Economics, and reported by George Avalos, “Santa Clara County has highest median household income in nation, but wealth gap widens,” San Jose Mercury News, August 11, 2014, accessed March 19, 2016: link.

(10) The 2010 U.S. Census found the median household income in Palo Alto, 2010-2014 (in 2014 dollars), was $126,771; the per capita income in the same period was $75,257; and the poverty rate was 5.3%. United States Census Bureau, QuickFacts, Palo Alto city, California, accessed March 26, 2016: link.

The poverty rate of 5.3% may include a higher proportion of families with children. For example, at Gunn High School, one of the two high schools in Palo Alto, 158 students, or 8.2% of students, received federally-funded free and reduced price meals in the 2010-2011 school year, the latest year for which I could find information. Palo Alto Unified School District, Henry M. Gunn High School Midterm Progress Report (Date of Midterm Visit March 22, 2012), Accrediting Commission for Schools, Western Association of Schools and Colleges, 8, accessed March 26, 2016: link. To put this into perspective, a household with four persons would qualify for subsidized meals if the household income is $44,863 or less. Palo Alto Unified School District School Nutrition Program Pricing Letter to Household (June, 2015), 2, accessed March 26, 2016: link.

(11) According to Fred Buelow, Treasurer of UUCPA, the congregation appears to have representation in each of the five quintiles of income distribution, with the smallest number in the lowest quintile. Personal communication, March 28, 2016.

(12) Words by Rev. Ginger Luke, a Unitarian Universalist minister of religious education.

(13) Haiti’s Papaye Peasant Movement (MPP) developed tire gardens to promote food security: “The concept of personal home gardens—in the city and in the countryside—carries great significance in a country where food security is hard to find.” Jessica L. Atcheson, “Ending Food Insecurity, One Urban Tire Garden at a time,” Rights Now: The Newsletter of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (Summer/Fall, 2013), 6-8.