Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) on Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), Ferry Beach Park Association, Saco, Maine. Photo courtesy of Carol Steinfeld.

Category: Road trips

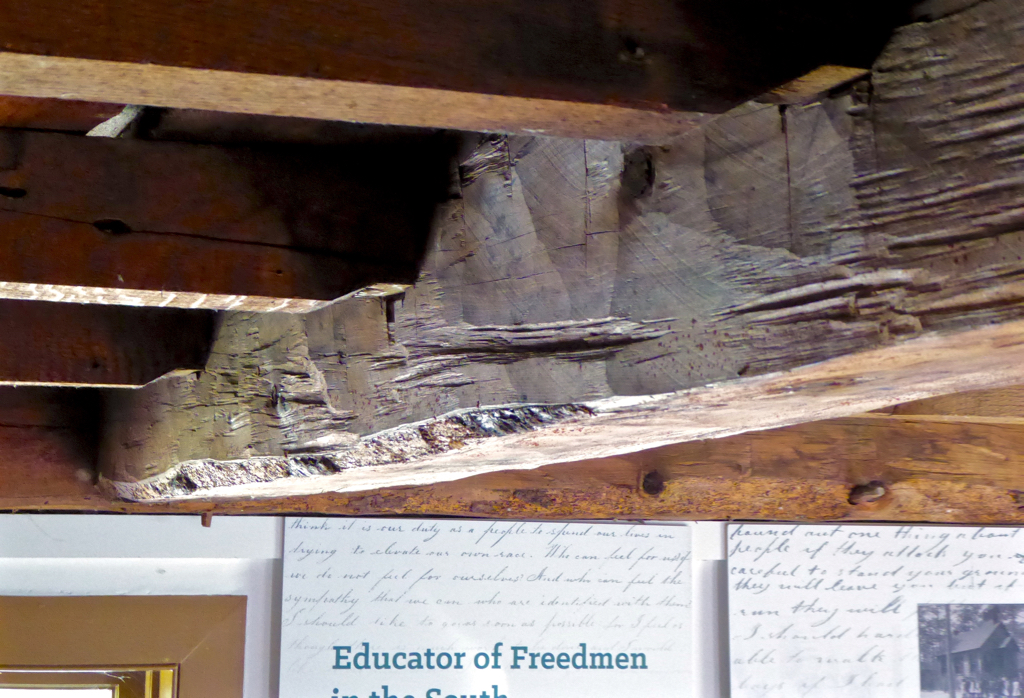

Beams, Concord, Mass.

Carol and I went to the Robbins House, an early nineteenth century historic house at the Minuteman National Historic Park in Concord, Mass. The house was originally occupied by Susan and Peter Robbins, two grown children of Caesar Robbins, and perhaps by Caesar Robbins himself; I say perhaps, because the history and chronology of the house, as set forth on the Robbins House Web site, is not entirely clear to me. This is not surprising, given how poorly documented African American lives of the early nineteenth century were. What’s important to know is that Caesar was an African American man who won his freedom from slavery by serving in the American Revolution, and the house was occupied by his descendants and extended family until about 1870.

We got an excellent tour from one of the interpreters, who told us a great deal about the people who lived there, and about the social history surrounding the house. But I have to admit what interested me was the construction of the house. I was particularly interested in the exposed roof beams in one room, which included both hand-hewn beams and sawn joists. The sawn lumber was manufactured using a vertical saw, not a rotary saw. Why the mix of hand-hewn and sawn lumber? The hand-hewn beams could have been salvaged from an older structure, something that was often done in the early nineteenth century, or they could have been made for that house; the sawn lumber could have replaced older joists, or they could have been original, though sawn lumber would have been more expensive than hewing one’s own beams. When the house was being restored, there were archaeology, dendrochronology, and other architectural studies were carried out; I hope the non-profit organization that operates the house publishes the tests and tells us why there are two kinds of beams.

Redding to San Mateo

We left Redding, in the narrow upper end of the great Central Valley, and headed south towards home. In the late morning, we stopped just south of Willows at the Sacramento River National Wildlife Refuge to walk the two-mile marsh loop.

There is something about being near wetlands that I find soothing: perhaps the big vista of sky you get from being in an essentially flat landscape; perhaps the nearness of an astonishing number of nonhuman organisms. Carol felt like walking fast and charged on ahead. I walked as fast as she, but stopped now and then to look at or listen to something: a mixed flock of White-fronted Geese, American Coots, Northern Pintails and other ducks swimming cautiously away from me; Marsh Wrens calling in last year’s dead and grey tule reeds; swarms of Red-winged Blackbirds flying across the marsh and up into the trees and back down into the marsh.

I stopped to look west towards the Coast Range in the distance, and the nearer ridge of the Great Valley Sequence, which, according to Roadside Geology of Northern and Central California, 2nd ed., “defines the boundary between the flat valley floor and the gaunt ruggedness of the Coast Range.” For someone raised among the smooth glaciated hills and mountains of New England, the mountains and ridges of California always look strangely ragged. This is a landscape defined by ongoing tectonic movement, not by the glaciers of fifteen thousand years ago.

A little later on, I stopped to spend ten minutes looking at an alkali meadow. The soil was almost white in places, the vegetation low and scraggy. It was not a very attractive place. Yet there were a number of game trails criss-crossing the meadow, and earlier I had seen a jackrabbit lopping off towards this meadow. In the distance, through the moist and hazy air, I could just see Sutter Buttes, the old defunct volcano that sits in the middle of the Central Valley.

I finelly caught up with Carol near the parking lot where we had started walking. It was time for lunch. We sat and ate at a picnic table near half a dozen bird feeders. The birds were cautious of us at first, but when they saw we probably wern’t a threat, they swarmed out of the tule reeds and nearby trees: White-crowned Sparrows, Yellow-crowned Sparrows, House Sparrows, Song Sparrows, Lesser Goldfinches, House Finches.

The rest of the ride home was unremarkable and dull. I read aloud from a bad murder mystery while Carol drove. The traffic got bad as we approached San Mateo. At last we arrived at home.

Seattle to Redding

We dropped off Saba at the Montessori school where she works, and started driving south. It was a gray and dreary day, and before long it started snowing. Pretty soon it was snowing hard enough that the ground was white on either side of the highway, and in a few places slush accumulated between the lanes. We saw some accidents: a couple cars spun out and off the highway, something on the northbound side of the freeway with several tow trucks and emergency vehicles and traffic backed up for a mile or more. South of Eugene, the snow stopped, but the forecast for the Siskiyou Mountains was for snow tonight and snow tomorrow morning. We decided to drive as far south as we could before we got tired. Wes topped briefly in Ashland so Carol could collect mineral water from the public fountain in Ashland Plaza. Then we started driving again, winding up over the mountains and back down again until we reached Redding, where we stopped to spend the night.

As for the lithium water, it smells sulphurous, like slightly rotten eggs. The water also has quite a bit of barium in it, so you’re not supposed to drink more than a few sips at a time. If we decide to drink it, we should do with it what they do with “Crazy Water” from Texas: dilute it; “Crazy Water” tastes pretty yucky, too, but once diluted it’s at least drinkable.

Phone booth, Kalama, Washington

San Mateo to Eugene, Ore.

We got up later than planned (and isn’t that how all our trips begin, getting up later than we had planned?), and immediately gave up on the idea of driving to Seattle in one day. Carol researched places for us to stay while I drove through the unpleasantness that is Bay Area traffic. We were glad to get off Interstate 80 and head north, away from the sprawling tentacles of the growing San Jose – San Francisco – Sacramento megalopolis.

I’ve been reading Roadside Geology of Northern and Central California, and when Carol started driving after lunch, I read to her from the section on driving Interstate 5 up through the Central Valley: it’s all Quarternary alluvial deposits, for miles and miles, with the one exception of the Sutter Buttes, a group of craggy hills that thrust up seemingly out of nowhere, a volcanic intrusion that seems incongruous.

The geology along the road got really interesting a couple of hours further north, but by that time we had moved on to other things. We sang some Sacred Harp songs, to get us ready for the Sacred Harp convention we’re going to this weekend, and then we sang some other songs — old standards like Moon River, Close to You, Ring of Fire — until I got the hiccups and had to stop.

We drove up, up, up over the Siskiyous, where there was some snow on the side of the road once we got above 4,000 feet, and then down, down, down into Ashland where we stopped for dinner. We saw a lot of street people in Ashland. Two of them accosted us as we walked towards a restaurant. “Hi, how are you?” the young white man said. “Good, how are you?” I said. “Poor and hungry. Can you give us a dollar?” he said. “We’ll stop on the way back,” Carol promised, and we did, but they were gone: it had gotten pretty chilly by then.

As we approached Eugene, we talked about Steve who had lived in Eugene. Steve was someone we had hung out with at the Alaska Sacred Harp Convention in October, and he had died suddenly and unexpectedly in California last month at the age of 60. He was not someone you would expect to die suddenly, and we keep talking about it, trying to make sense out of his death.

And then we were at the motel, where they were showing Olympic ski jumping competitions on a big TV. I talked to one of the young men staffing the desk while Carol checked in. “What they have on right now is figure skating or ski jumping,” he said apologetically. “I don’t need to see figure skating,” I said. He grinned. We talked about all the sports they never seem to show. “Like curling,” I said, “ho come they never show curling?” “It’s pretty boring,” he said, “it’s like people who weren’t good enough to play hockey had to invent a sport they could play.” It turned out that he enjoyed shooting, and shot both pistols and rifles; we both agreed that we would like to see the Olymplic biatholon competition, where you have to ski a certain distance, then shoot. We both looked up at the big screen as another ski jumper twisted through the air in slow motion, then landed wrong and tumbled down the hillside.

Lichens, Camp Meeker, Calif.

These lichens were growing on reddish soil exposed by a road cut, in the redwood forest above Camp Meeker, California. The lichens in both photos are approximately the same size; in the first photo, the edge of a nickel appears at lower left to provide a sense of scale.

As to identification, these lichens are in the genus Cladonia: the primary thallus consists of whitish-green squamules (the little leaf-like things at the bottom of the organism); and arising from the squamules is the podetium, an upright structure characteristic of the genus Cladonia. But to determine which species of Cladonia, I would have had to collect some samples and carefully examined them. In Lichens of California, Mason E. Hale Jr. and Mariette Cole state that “Cladonia is one of the first lichens collected by amateurs; since I am a rank amateur when it comes to lichens, it is thus no surprise that I paid so much attention to these showy and fascinating lichens.

Moving

Carol and I have decided that it’s easier to move a thousand or more miles away, as we have done four times now, than it is to move two miles away, as we are doing right now. When you are contemplating a long distance move, you know you have to plan everything well in advance. When you’re moving two miles up the street, you think it’s going to be easier, so you relax.

But a move of two miles is not much easier than a move of two thousand miles. Friday, while we were in the middle of schlepping boxes, Carol looked at me and said, “This is traumatic.” OK, maybe “traumatic” is too strong a word; it certainly is extremely unpleasant.

Mount Edgecumbe

Carol and I are here in Alaska to participate in the Alaska Sacred Harp Convention, and we have been singing every day, and we attended a “singing school,” pretty much as you’d expect. But our gracious host Kari also arranged for those attending the convention to go on a whale watch trip. Over the course of an hour and three quarters on the water, we saw more than twenty humpback whales — and the scenery was spectacular as well. I particularly enjoyed looking at Mt. Edgecumbe, a long-extinct volcano. At this season Mt. Edgecumbe is snow-clad from it summit about halfway down to the sea, making it look like something out of a classic Japanese woodblock print, only more dramatic.