Vivid dreams occupied me all night, though I didn’t remember any of them when I awakened in the morning. Perhaps they were anxiety dreams, or dreams of overwork; with Peace Camp and the youth service trip and my ordinary tasks, I worked pretty much seven days a week in the three weeks leading up to vacation.

We got up late, and after I ate breakfast we walked over to the Needles Point Pharmacy. I needed razors, and Carol needed a needle to sew up a shirt.

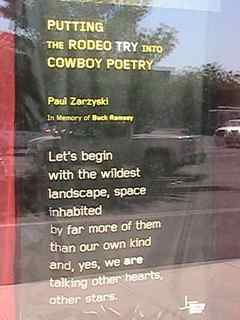

Above: Needles, Calif.

The store was pretty big on the inside. I found the razor blades I wanted, and then Carol and I wandered around looking at everything they had. They seemed to have everything. In addition to the usual drugstore merchandise, they had in stock: jigsaw puzzles, Hummel figurines, 3.5 inch diskettes for your computer, writing tablets with air mail paper, a bright red Mickey Mouse travel alarm clock in yellowed plastic packaging, and brand new Clairol blow dryers dating from the 1980s. On a whim, I bought some air mail paper from the very pleasant woman behind the counter.

When we finally started driving, the thermometer outside the motel office read 110 degrees.

Carol drove for most of the day, while I dozed, and read aloud to her from Agatha Christie’s Murder at Hazelmoor. It seemed odd to be reading about a murder in country house in England in the middle of a dark snowy winter, when we were driving through the wide open, sun-filled southwest.

We stopped for some caffeine at a gas station in Navajo, Arizona. While I was in the gas station, Carol wandered over to where a man was selling jewelry that he had made. When i got there, Carol was trying to decide if she liked one of his necklaces. I got to talking with him. He had been born in the area, half Navajo and half Hopi, and he spoke both languages as birth tongues. Then he had been relocated to a Mormon couple in Utah; enlisted in the Army and served in Vietnam; went to college in Provo on the G.I. Bill; and then had lived in Greece, the Bay area, and several other places I have now forgotten.

He was a big supporter of Barack Obama. “He’s the only president who has done anything for Native Americans,” he said. We agreed that, regardless of his merits, that some of the criticism of Obama was due solely to the fact that he wasn’t white. “White people really like to be right,” he said, and I gave a snort of laughter at the truth of that statement. That got us into a discussion of race and racism, during which I insisted that the Boston area, where I grew up, was the most racist place I have ever lived. “Even the white people hate each other in Boston,” I said, thinking of the Yankees, Irish, Italians, and French Canadians. He agreed with me, though I wasn’t convinced he knew anything about Boston.

Above: Navajo, Ariz.