Part Twoof a history I’m writing, telling the story of Unitarians in Palo Alto from the founding of the town in 1891 up to the dissolution of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1934. If you want the footnotes, you’ll have to wait until the print version of this history comes out in the spring of 2022.

The Unitarian Church of Palo Alto Begins, 1905-1910

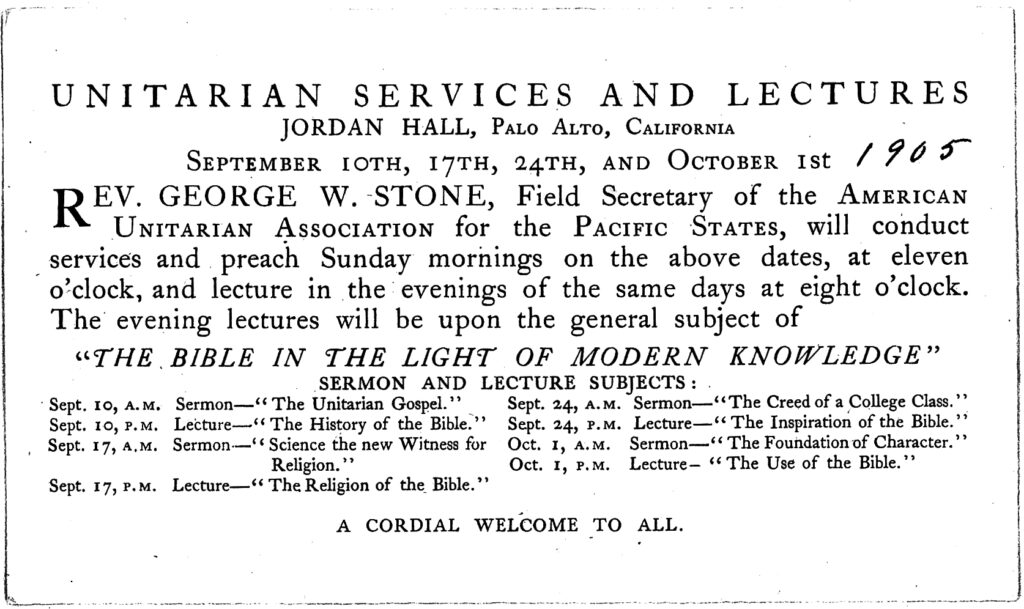

In 1905, Helene and Ewald Flügel invited Rev. George Whitefield Stone, the Field Secretary of the American Unitarian Association for the Pacific States, to come to Palo Alto to christen their children. When Stone arrived in September, 1905, the Flügel children were aged 4, 10, 13, and 15 years old. The family had lived in Palo Alto since 1892; it may be Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes had christened the two eldest children in 1895. In any case, Stone came to Palo Alto, and while there he conducted Unitarian services each Sunday from September 10 through October 8. At the conclusion of the service on October 8, Stone said he was willing to continue with weekly worship services if those assembled showed sufficient interest. Karl Rendtorff made a motion “that a Unitarian Church be formed at once,” giving Stone the authority to appoint a “Provisional Committee” to transact any necessary business until a regular congregational organization could be formed. The motion was seconded by Melville Anderson, and “carried by a rising vote.”

Stone promptly appointed five men and two women to the Provisional Committee: Melville Anderson, John S. Butler, Henry Gray, Agnes Kitchen, Ernest Martin, Fannie Rosebrook, and Karl Rendtorff, who became the Secretary-Treasurer. Melville Anderson, Henry Gray, Ernest Martin, and Karl Rendtorff were all professors at Stanford. John Butler and Fannie Rosebrook had both been on the executive committee of the old Unity Society. Agnes Kitchen was active in civic affairs in Palo Alto, including the Woman’s Club. Once again, women filled leadership positions in the new Unitarian congregation from the very beginning.

Just two weeks later, on October 23, the women formed their own Unitarian organization. The Women’s Alliance, formally known as the “Branch Alliance of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto,” became a local chapter of the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Women. How did the Palo Alto women decide to form their own Branch Alliance so quickly? Perhaps George Stone promoted the idea. The national organization existed to “to quicken the life of our Unitarian churches,” which would have suited Stone’s goal of building a self-sustaining Unitarian church. But it’s equally possible that some of the women had already belonged to a Unitarian women’s group. The National Alliance had roots in several earlier organizations, including the Western Women’s Unitarian Conference, organized in St. Louis in 1881; Emma Rendtorff and her mother Emma Meyer were active Unitarians in St. Louis in that year. Closer to Palo Alto, the women’s organization of the San Francisco Unitarian church, called the Channing Auxiliary had been active in promoting Unitarianism along the entire Pacific Coast ever since it was formed in 1873; perhaps some of the early members of the Palo Alto Alliance had contact with the Channing Auxiliary.

Continue reading “Unitarians in Palo Alto, 1905-1910”