![]() It’s time to approximate the ratio between circumference and diameter yet again today! (If you want to notate thirty seconds as five tenths of a minute, you could celebrate at thirty seconds after 9:26.)

It’s time to approximate the ratio between circumference and diameter yet again today! (If you want to notate thirty seconds as five tenths of a minute, you could celebrate at thirty seconds after 9:26.)

Category: Bay area, Calif.

Web of relationships

Today I was at Pescadero Marsh to look at live birds, but the dead things proved more interesting. It was just after low tide, and I saw two empty crab shells (prob. Red Crabs, Cancer productus), looking as though they had been eaten by gulls; interesting, but a pretty common sight, and it’s more interesting to actually see a gull eating a crab. Then I found the empty shells of two small crustaceans, organisms I’d never seen before. Here’s one of them:

I have no idea what species this is, though I suspect it’s a fairly common organism.

Later, I walked along the dike near Butano Creek, and came across a dead mole (the notebook next to the mole is marked in inches):

Given the size of those front feet and the short tail, I’d say it was a Broad-footed Mole (Scapanus latimanus). This is the third dead mole I’ve found in six months.

What interests me when i see dead things in the field is trying to figure out how they died, and how they are tied in to the ecosystem. The Red Crabs were easy to figure out — probably eaten by gulls. But why did that little crustacean die? it didn’t look as though another organism had tried to eat it, so was it simply left high and dry at low tide? As for the Broad-footed Mole, there was a definite hole in the other side of the animal, which could have been made by a bird’s bill; I saw Red-tailed Hawks and Northern Harriers hunting in the marsh; perhaps a raptor killed the mole, then got scared away before it could eat.

These are just possible scenarios; I’ll never know what really happened; but what I do know is that somehow these dead creatures reveal something about the web of relationships between organisms.

Pescadero Marsh

I went for a walk in Pescadero Marsh for the first time today. It’s a pretty remarkable place. It encompasses a variety of habitats, including pickleweed salt marsh, freshwater marsh, riparian corridor, sandy beach, old sand dunes, etc. Birdlife ranged from birds typical of beaches, like Sanderlings and Black Turnstones; to birds typical of freshwater marshes, like Marsh Wrens and Common Yellowthroats.

There were signs of other resident animals as well. Along the edge of Pescadero Creek, you pass by what look like big piles of sticks, but they’re actually houses built by Dusky-footed Wood Rats (Neotoma fuscipes). In the photo below, the tape measure at lower left is extended to 12 inches (300 cm); so this particular wood rat house is about four feet high (1.3 m).

From a little further down the same trail, you can see a Great Blue Heron rookery. Their nests look like big piles of sticks, piles that may be three or more feet from bottom to top, that somehow got stuck high up in the branches of dead trees. I counted at least eight herons sitting on nests — four foot high birds roosting on three foot high piles of sticks thirty or forty feet above the ground.

On a secluded part of the beach on the other side of Highway 1, an immature Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus) was too stupid, or too dazed, to move away when I walked past it. It stood quite still while I took its photo (above). The other birds and animals I saw were far less trusting than this cormorant: as soon as humans came into view, they flew or scuttled away out of danger. Except for the fifty or so Elephant Seals I saw lying on the rocks out beyond the beach: they did not seem to pay any attention to the humans walking on the beach; but then, they were well out of reach of any meddling humans, protected by a couple hundred feet of surf and slippery rocks.

Malcolm

Malcolm X was shot to death on February 21, 1965 — fifty years ago.

Of the two most prominent figures of the Civil Rights Era, I feel more religiously aligned with Malcolm X than with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I find Dr. King to be a forbidding figure. Dr. King’s writing, his preaching, and his speaking were all extraordinary. Dr. King not only stayed true to his principle of non-violence in the face of actions that would make just about anyone else retaliate in anger, but he also managed to lead his many thousands of followers to maintain their commitment to nonviolence as well. Dr. King intimidates the hell out of me, and makes me realize my own utter inadequacy as both a minister and a human being.

Of course, Malcolm X is a forbidding figure as well. His father was murdered by whites, and his mother then went into an insane asylum, leaving Malcolm X effectively an orphan. Malcolm was imprisoned, yet in prison he had a religious awakening, got himself straightened out, and educated himself. He wound up becoming one of America’s most compelling religious leaders. Malcolm X intimidates the hell out of me, too: I have no doubt I would crumple under that kind adversity, and he too makes me realize my own utter inadequacy as both a minister and a human being.

I’m a pacifist, but I still feel more aligned with Malcolm X than with Dr. King. I think it’s because I better understand Malcolm X’s way of writing. He was a master of the plain style. In his book The Ballot or the Bullet, he wrote: “Three hundred and ten years we worked in this country without a dime in return — I mean without a dime in return. You let the white man walk around here talking about how rich this country is, but you never stop to think how it got rich so quick. It got rich because you made it rich.” This is stating a simple fact as clearly as possible. Perhaps it lacks some of the literary finesse of, say, “Letter form Birmingham Jail”; what it lacks in finesse it gains in clarity.

Reading Malcolm X is a bracing experience for me. Recently, I’ve been questioning this notion of “white privilege” that we white liberals have been playing around with for twenty-five years or so. In The Ballot or the Bullet, Malcom X writes: “Whenever you’re going after something that belongs to you, anyone who’s depriving you of the right to have it is a criminal. Understand that. Whenever you are going after something that is yours, you are within your legal rights to lay claim to it. And anyone who puts forth any effort to deprive you of that which is yours, is breaking the law, is a criminal.” This simple, clear statement puts the lie to the concept of “white privilege”; what we’re actually talking about is theft, a criminal act, a crime; it’s not white privilege, it’s white theft.

One of Malcolm X’s clearest statements comes from his Autobiography. Yes, the Autobiography of Malcolm X was written in collaboration with Alex Haley. But Haley based the book on extensive interviews and conversations, and I have enough trust in Haley’s skill as a writer to trust him to accurately record Malcolm X’s words in key passages. And when I read the following passage, I can hear the clarity of language and thought that belong Malcolm X, not Alex Haley:

“Since I learned the truth in Mecca, my dearest friends have come to include all kinds — some Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, agnostics, and even atheists! I have friends who are called capitalists, Socialists, and Communists! Some of my friends are moderates, conservatives, extremists — some are even Uncle Toms! My friends today are black, brown, red, yellow, and white!”

An essential religious insight into theological anthropology; a plainly spoken insight that needs to be heard clearly by people throughout America.

Malcolm X was murdered at age 39: a sorry waste of a brilliant mind.

Amphibian

This afternoon I was walking in Purissima Creek Redwoods Open Space Preserve, through Douglas Fir woodlands, along a ridge that was about 1,400 feet aboe sea level. I happened to look down at my feet, and there was a — well, no, it wasn’t a lizard, it was some kind of salamander.

Sometimes it pays to walk slowly and deliberately. I got down on my knees to look more closely.

I haven’t seen seen a salamander since I moved to California more than five years ago, so I stopped to watch it for a while. I placed a quarter on the ground, to give a sense of scale in the photos I was taking. The salamander obligingly stepped right on the quarter:

It was fun to watch it walk — it had that rolling, deliberate salamander gait, so very different from the quicker-than-the-eye sprinting done by lizards. Eventually, it walked off the trail and disappeared into the leaf litter.

When I got home, I looked on the California Herps online identification guide. I’m pretty sure it was a Rough-skinned Newt (Taricha granulosa). Another possibility would be the Red-bellied Newt (Taricha rivularis) — but the eye of my newt showed some whitish yellow, while T. Rivularis has uniformly dark eyes.

Invertebrate pitfall trap

When we humans think about the interdependent web of life, we tend to think about the relationships between ourselves and familiar organisms like mammals and trees. These are organisms that are either larger than us or relatively close to us in size, or they are taxonomically close to us. But if you conduct a survey of biodiversity in a given tract of land, the majority of non-microscopic species you find will be invertebrates, e.g., insects, spiders, crustaceans, etc. For a more realistic theological understanding of the web of life, I think it’s necessary to develop a more realistic understanding of biodiversity. It is easy and fun to feel a connection through the web of life to relatively cute organisms like rabbits, and to relatively majestic organisms like redwoods. Understanding our connections with organisms that are not particularly cute or majestic expands our idea of the interdependent web of life.

A few years ago, I participated in a blogger’s bioblitz; a bioblitz is a study that provides a “snapshot of biodiversity.” One of the tools used in a bioblitz is an insect pitfall trap; this kind of trap provides a sampling of insects and other invertebrates. I decided to place an insect pitfall trap in our front yard, so I could see some of the invertebrates that live in our urban setting.

Some online research revealed that pitfall traps made of glass are most effective (Oecologia 9. VI. 1975, Volume 19, Issue 4, pp 345-357), but the easiest way to make a pitfall trap is with nested plastic drinking cups. You dig a hole deep enough to bury the two nested cups, and pack dirt around them so that the rim of the upper cup is exactly at ground level. Then you can remove the upper cup, dump out all the dirt that fell into it when you were burying it, and then replace it. I used two nested 10-ounce clear plastic drink cups:

To use pitfall traps ethically, you should check them at least once a day, and either release the captured organisms or collect them responsibly. If you’re expecting rain or hot sun, you should place some sort of cover over the trap, raised up an inch or two. The cover will keep rain and sun out, but still allow invertebrates to crawl into the trap. If you’re no longer going to use the trap, pull it out of the ground.

Here’s what I found in my pitfall trap this afternoon:

The large organism appears to be in the genus Stenopelmatus; from looking at online identification guides, I’d guess this organism is probably a Dark Jerusalem Cricket (Stenopelmatus fuscus [Haldeman, 1852]). Where does it fit into the web of life? According to the Nevada at Reno Department of Extension: “Because it is nocturnal and comes out of the ground at night to roam around, owls, including the endangered spotted owl, feed on it. Probably other nighttime predators such as coyotes, foxes, and badgers eat it as well.” As for their food sources, the Orange County (Calif.) Vector Control District (OCVCD) says the primary food sources of Jerusalem Crickets are “plant roots and tubers; however, “they also feed on other insects, even their own kind.” The OCVCD also states that Jerusalem Crickets do not pose a health threat to humans.

The other organisms in the trap — you can see something like a centipede under the Jerusalem Cricket’s left antenna — were too small for me to have any hope of identifying. Besides, if I’m going to accurately identify insects and similar invertebrates, I’d need to ask an entomologist equipped with powerful binocular microscope.

Mammal signs

Yesterday, Carol noticed some scat and other mammal signs in our garden. First, something has been eating the tree kale Carol has been growing. The bitten-off leaves and stems are some 425 mm / 17 inches from the ground:

This seems a little high off the ground for rabbits. According Jameson and Peeters Mammals of California, the rabbit most likely to be found in our area is Audubon’s Cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii). The total length, from nose to tail, of Audubon’s Cottontail is 370-400 mm, or about 15 inches; it would be a stretch (but possible) for a rabbit that size to reach up 425 mm to nibble on stems and leaves.

Right next to the tree kale is a deposit of scat: many small pellets, all about 5-7 mm in diameter. This, according to Olas Murie in A Field Guide to Animal Tracks would be absolutely typical of cottontails. But it may be coincidence that there’s a deposit of cottontail scat right next to the bitten-off twigs, and it could be that a deer got into our yard; Carol has seen deer down the cul-de-sac on which we live, and we suspect that they move up and down San Mateo Creek, which is less than a block from our house.

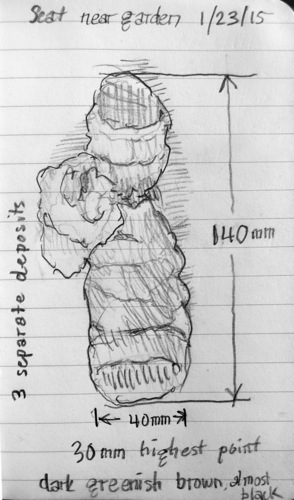

There’s another scat right next to another of our garden beds. Here’s my sketch of it:

The lack of taper on the ends, and the relatively large size, leads me to believe that these are raccoon scat. Murie says that raccoon scat can be difficult to identify, and “may be confused with the larger skunks and opossum.” But given the size — on the large size for raccoons, probably too big for skunks or opossums — and the fact that we regularly see raccoons at night in our garden, I’m going to guess this is from a raccoon.

Sacred Harp Convention

Once every three years, the All-California Sacred Harp Convention comes to the Bay area. It’s going on this weekend.

What is Sacred Harp, you ask? It has nothing to do with harps, but you sing from a book called The Sacred Harp. At a Sacred Harp convention, you sing for three hours in four-part harmony at the top of your lungs along with 150 other singers who range in age from 8 to 80-something. Then you break for this fabulous potluck lunch, where you eat more good food than you can believe. Then you go back sing again for another three hours in the afternoon. Then you go back the next day and do it all over again.

Ants

Recently, I stumbled across the AntWeb site, sponsored by the California Academy of Sciences. Once you create a login (and all you have to provide is a username and password, no other info), you have access to tons of photographs of ant specimens, taken through a powerful microscope. Of particular interest to me is the online field guide to California ants, with photos of nearly all of the 270 resident species. The curator of the California pages writes:

“Prominent California ants include seed-harvesting species in the genera Messor, Pheidole and Pogonomyrmex; honeypot ants in the genus Myrmecocystus; a diverse array of species in the genera Camponotus (“carpenter ants”) and Formica; native fire ants (Solenopsis spp.); velvety tree ants (Liometopum spp.); and the introduced Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). This last named species is particularly common in urban and suburban parts of California, where it establishes dense populations and eliminates most native species of ants.”

I’ve always thoughts ants were interesting creatures. Now having looked through dozens of photos of ants I will go further and say that they are beautiful creatures. Even the Argentine ant appears beautiful, in spite of the destruction it does to native arthropods.

I am also fascinated by the written descriptions; these descriptions have their own kind of beauty, which may be found in their economy and laconic precision. Here, for example, is how to identify the Argentine ant — remembering that you will need a powerful binocular microscope to see all these details:

“Diagnosis among workers of introduced and commonly intercepted ants in the United States. Antenna 12-segmented. Antennal scape length less than 1.5x head length. Eyes medium to large (greater than 5 facets); do not break outline of head; placed distinctly below midline of face. Antennal sockets and posterior clypeal margin separated by a distance less than the minimum width of antennal scape. Anterior clypeal margin variously produced, but never with one median and two lateral rounded projections. Mandible lacking distinct basal angle. Profile of mesosomal dorsum with two distinct convexities. Dorsum of mesosoma lacking a deep and broad concavity; lacking erect hairs. Promesonotum separated from propodeum by metanotal groove. Propodeum with dorsal surface not distinctly shorter than posterior face; angular, with flat to weakly convex dorsal and posterior faces. Propodeum and petiolar node both lacking a pair of short teeth. Mesopleura and metapleural bulla covered with dense pubescence. Propodeal spiracle bordering posterior margin of propodeal profile. Waist 1-segmented. Petiole upright and not appearing flattened. Gaster armed with ventral slit. Erect hairs lacking from cephalic dorsum (above eye level), pronotum, and gastral tergites 1 and 2. Dull, not shining, and color uniformly light to dark brown. Measurements: head length (HL) 0.56–0.93 mm, head width (HW) 0.53–0.71 mm.”

Last sunset of 2014

Carol and I drove over to Half Moon Bay late this afternoon to watch the sun set into the Pacific Ocean for the last time this year.