Rev. Clarence Reed served longer than any of the other ministers of the old Palo Alto Unitarian Church, for six years from 1909-1915. Arguably, these were the best years for the congregation: they built the social hall that had been originally planned; the Sunday school grew to perhaps 60 children and teenagers; the Women’s Alliance had perhaps 40 members; and perhaps 200 adults were affiliated with the congregation. Here are documents that tell the story of the congregation during these years:

Rev. Florence Buck in Palo Alto (1910)

[Rev. Florence Buck was one of the better known women who served as Unitarian ministers in the early part of the twentieth century. During her brief stay at Palo Alto, she inspired at least one teenaged girl to become a minister — more on that teenager in a subsequent post on the Palo Alto Unitarians.]

Rev. Florence Buck has been given a year’s leave of absence at Kenosha, Wis., and is supplying the pulpit at Palo Alto, Cal.

— Unitarian Word & Work (Boston: American Unitarian Association), October, 1910, p. 5.

Mr. Reed, the minister of the Palo Alto Society, has been ill, but hopes to take up work again in December. His pulpit mean-time is being supplied by Rev. Florence Buck.

— Unitarian Word & Work (Boston: American Unitarian Association), November, 1910, p. 8.

WOMAN MINISTER TO FILL PULPIT

Rev. Florence Buck Has Been Chosen Pastor of Unitarian Church of Alameda

Alameda, [Calif.,] Dec. 19. — Rev. Florence Buck has accepted a call to become the minister of the First Unitarian church of this city. She will begin her pastorate Sunday, January 1, on which date she will conduct services and deliver her initial sermon. She will be the first divine of her sex to take permanent charge of a local church and will be one of the few women ministers in service on the Pacific coast.

The new minister is unmarried. She has had extensive experience In religious work and has been a preacher of the Unitarian faith for some years. She was associated with Rev. Marian Murdock in conducting a church in Cleveland, O. She also filled the pulpit of a Unitarian church in Kenosha, Wis. Of late Rev. Miss Buck has been temporarily occupying the pulpit of the Unitarian church in Palo Alto in the absence of the regular minister, Rev. Clarence Reed, former pastor of Alameda Unitarian church, who is on a vacation in Japan. Since Rev. Mr. Reed left here and went to the Palo Alto church the First Unitarian church has been without a regular pastor. Rev. J. A. Cruzan, field secretary for, the Unitarian society or America, has been acting temporarily. Rev. Miss Buck was heard here twice in the pulpit: of the Unitarian church last month. On both occasions she made a good impression and the trustees decided to extend her a call.

— San Francisco Call, vol. 109, no. 20, December 20, 1910, p. 11.

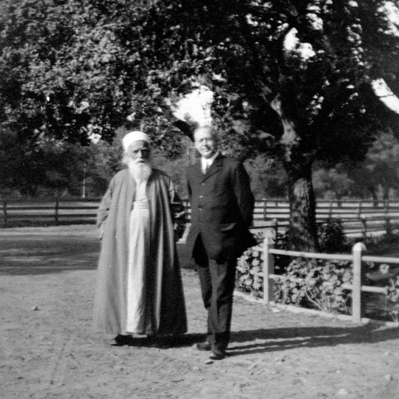

Above: Rev. Clarence Reed and the Baha’í prophet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palo Alto, 1912