From 1995 to 1998, I published a science fiction fanzine. This was before people published their fanzines on the Web, so it was photocopied, stapled, and mailed out. What eventually killed it off was the cost of printing and mailing two or three dozen copies; I didn’t have much money in those days.

It’s hard to explain the whole subculture which surrounded science fiction fanzines in the days before the Web. It’s important to know that there were several different types of fanzines: genzines, with multiple authors writing on topics of general interest to all science fiction fans; personalzines, written by a single person who wrote about whatever interested them; newszines, with news of science fiction fandom. Most fanzines were personalzines; genzines and newszines required a higher level of skill. Fanzines were distributed in several different ways: apazines were distributed through an APA, or Amateur Press Association, where fanzines of APA members were collated and distributed to all the members; a clubzine was distributed to the members of a science fiction club; but most fanzines were made available for the “The Usual,” which meant there were three ways to get a copy: send a letter of comment (LoC), send some modest sum plus a self-addressed stamped envelope; or send your own fanzine in trade. I started a fanzine primarily because I needed something to trade for other fanzines. Other science fiction fans, called “letterhacks,” fed their fanzine habit by writing innumerable letters of comment. And many fanzines carried reviews of fanzines they had received, along with the editor’s address. Fanzine subculture was really a social network organized around the written word; in a very real sense it can be seen as a precursor to today’s online social networks, because a significant proportion of the users of the earliest social networks — BBSs, Usenet, etc. — were science fiction fans, and those early users shaped later social networks. It is not a coincidence that one of the very first web logs, or blogs, was written and hand-coded by Poul Anderson, a science fiction author.

The other part of science fiction fandom’s social network was, and still is, conventions. A science fiction convention was where you met face-to-face the people that you had come to know through reading fanzines and writing letters of comment. Or maybe you didn’t meet those other people: many science fiction fans were (and are) strongly introverted, and a feature of some of the science fiction conventions I attended were sessions in which a whole bunch of people sat in a room together and read books; no one talked. To those of you who are extroverted, this will sound crazy, but for those of us who are strong introverts, this sounds like the perfect way to be social, and even though I never attended one of those sessions it was comforting to know they were an option. Science fiction conventions also attracted a fair percentage of people whom we would now call neuroatypical; it was normal to be neuroatypical at a science fiction fan, just as it was normal to be socially awkward, or to be socially adept, or to be neurotypical. Science fiction fans, in my experience, could be a very tolerant group of people; though at the same time, science fiction fandom has always been subject to intense feuds and violent arguments (to read about a recent science fiction kerfluffle, do a Web search for “rabid puppies hugo”). These conflicts, of course, made wonderful material for several months’ worth of fanzines and letters of comment, and a regular feature of most fanzines was “convention reports,” where someone would tell in excruciating detail all about their experience at some science fiction convention; and the next issue there would be letters commenting on the convention report, and later more letters commenting on the comments, and so it could go on for months. And of course the WordCon — the annual world science fiction convention — was the biggest convention of all, the one which generated more fanzine column inches than any other.

This year’s WorldCon is in San Jose, and it going on right now. I thought about going. I’ve only been to one WorldCon, in 1980, and it would be fun to go one more time. Then I thought of the crowds of science fiction fans mobbing the San Jose Convention Center. I don’t like crowds, even crowds of tolerant people who do things like sit in a room together reading books and not talking. And I remembered years ago, when I was still publishing my science fiction fanzine, I wrote a con report which said, in essence, “I didn’t go.” So this is my con report telling you why I didn’t go to the WorldCon that took place a short drive from where I live.

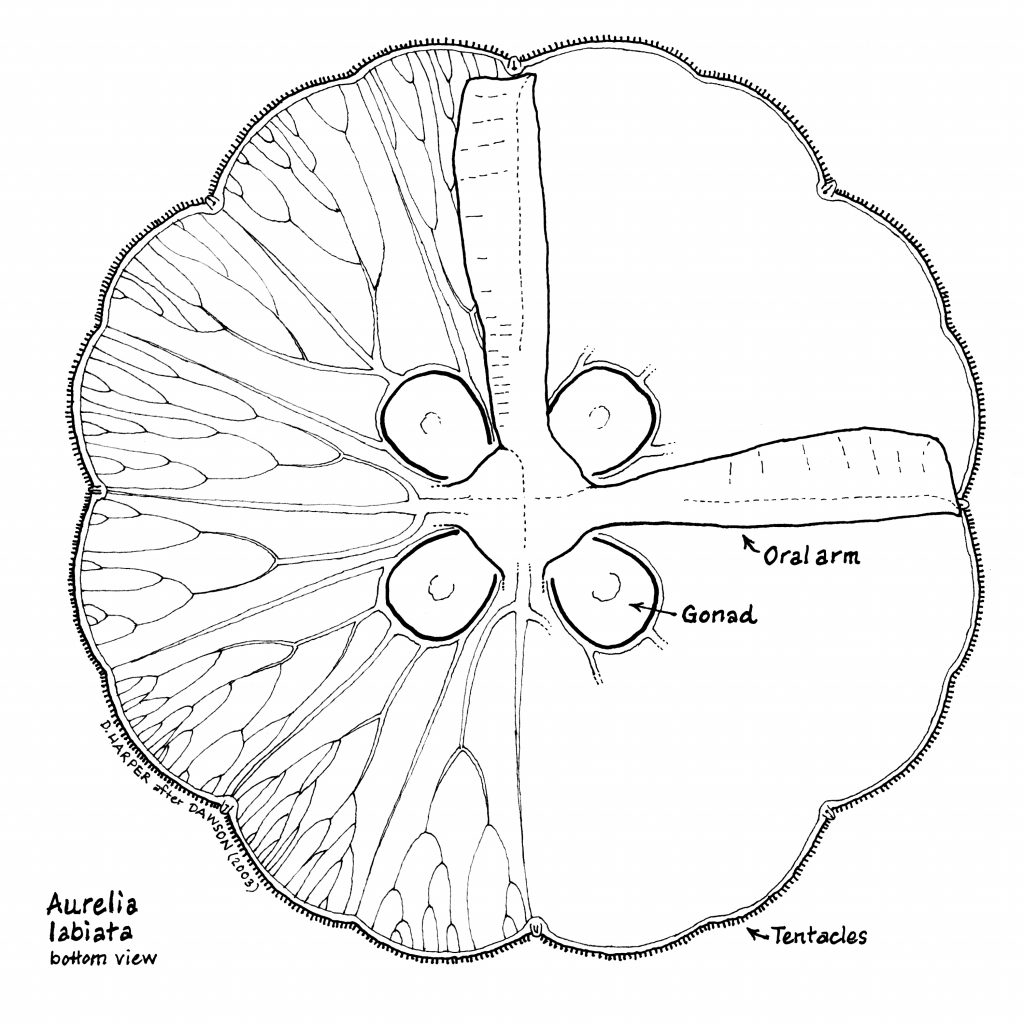

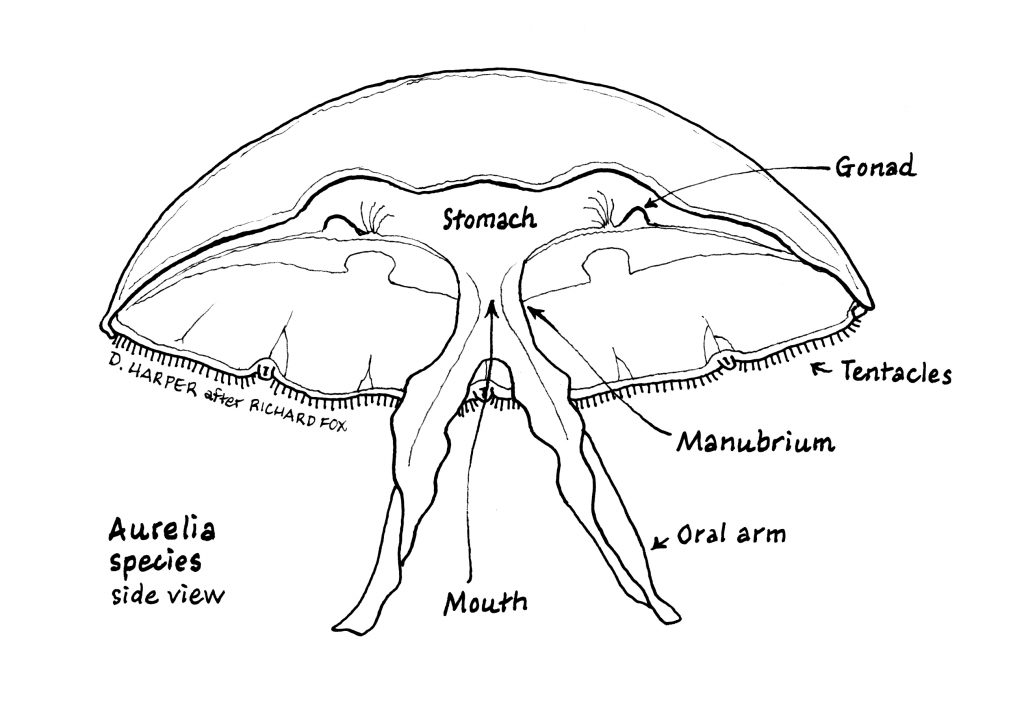

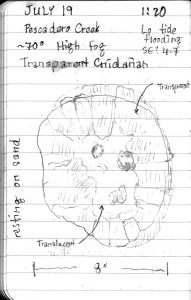

Drawings revised, July 20.

Drawings revised, July 20.