A group of Christian evangelicals have published a book titled “The Spiritual Danger of Donald Trump.” In an interview with Religion News Service, the editor, Ronald J. Sider, founder of Evangelicals for Social Action, answers the question, “So what is the spiritual danger of Donald Trump?”

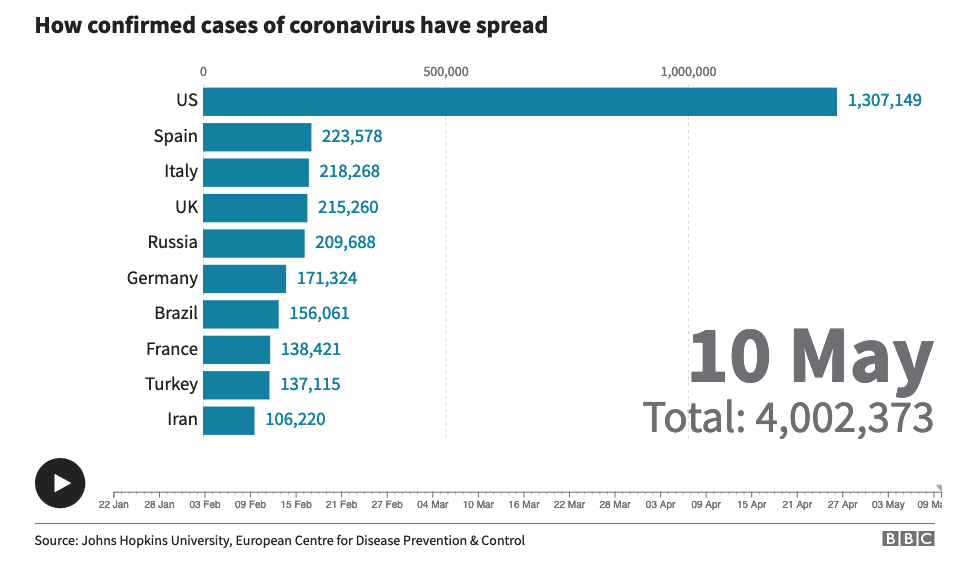

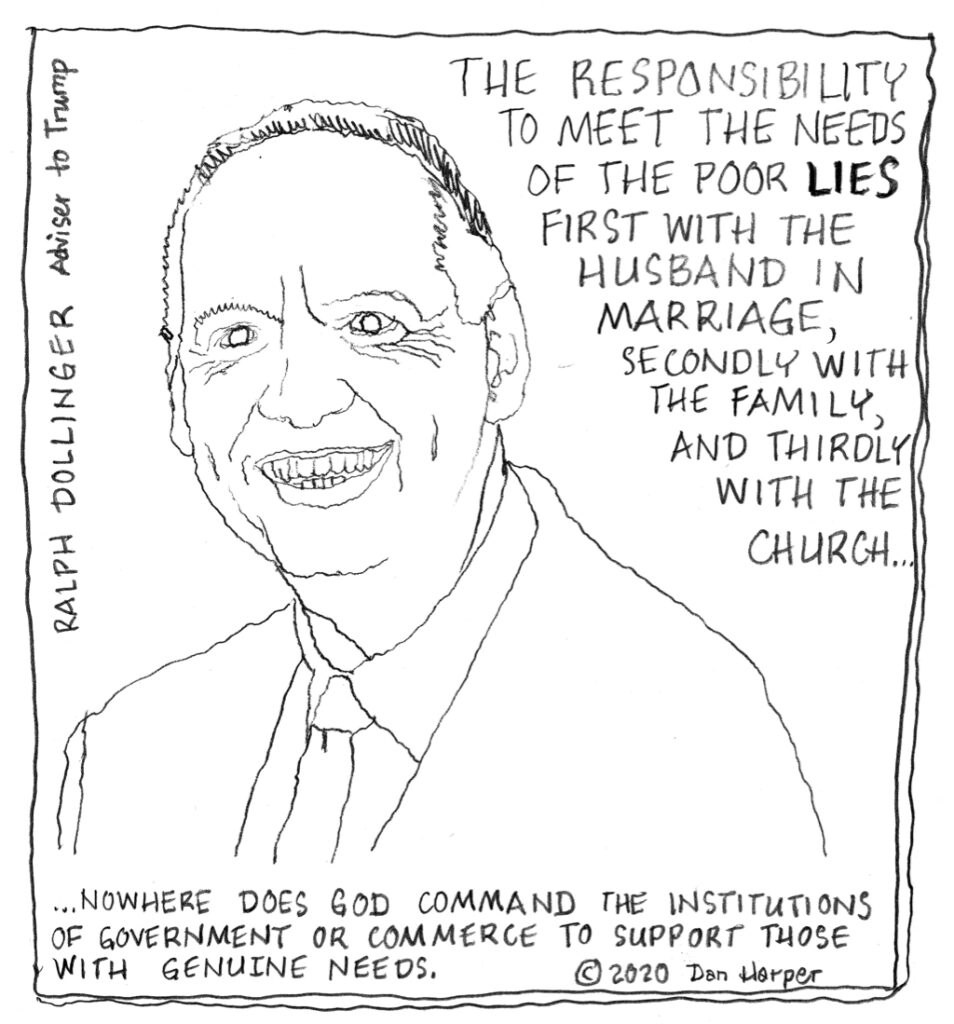

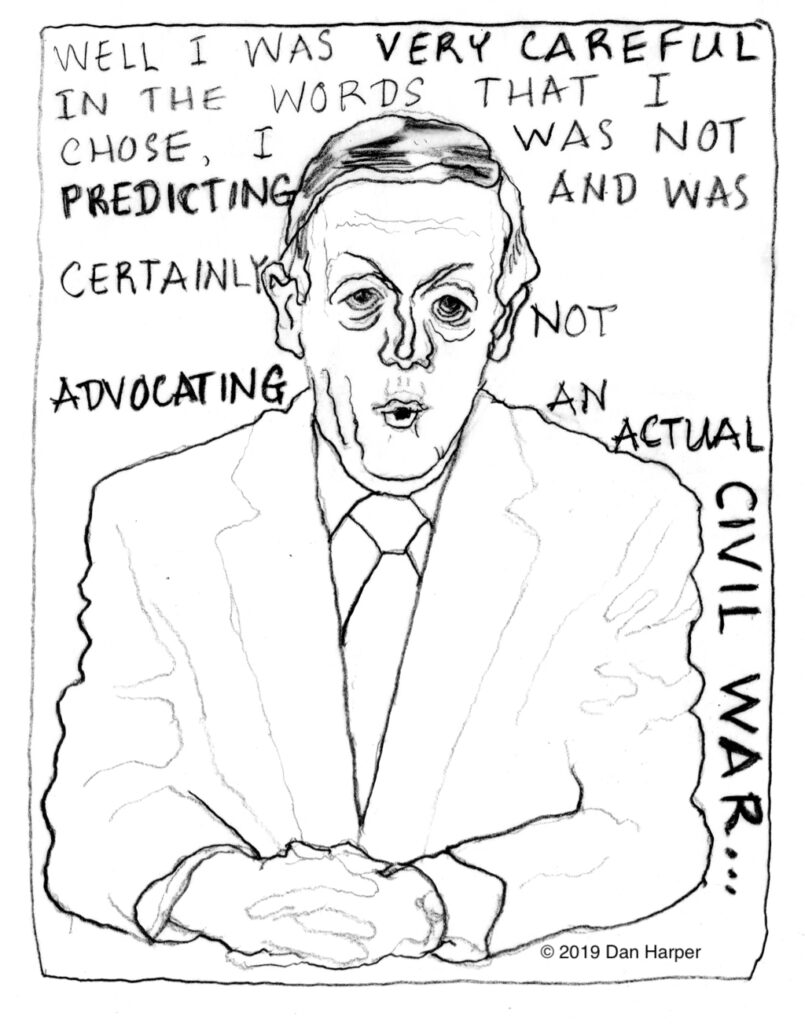

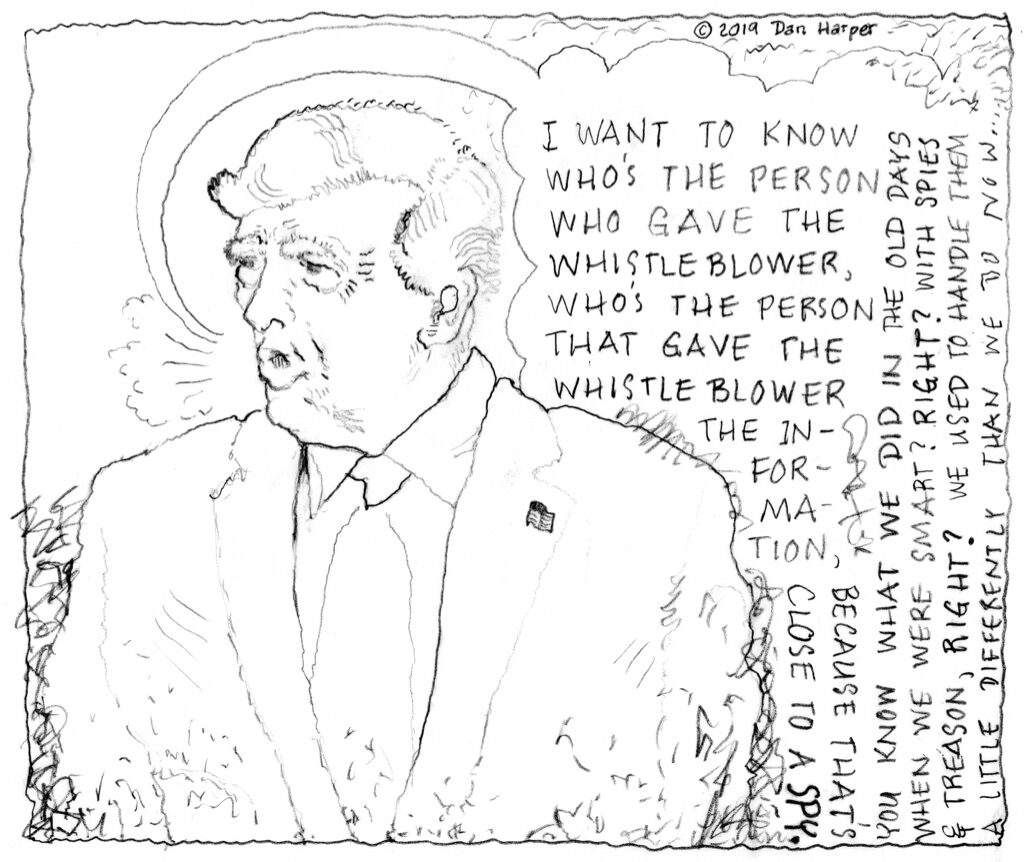

“I would summarize it this way [Sider says]: Trump lies constantly. He has repeatedly demonstrated adulterous sexual behavior. He fails to make justice for the poor a concern in his policies. He constantly stokes white racism. His response to COVID-19 was dreadfully weak in the first couple of months. His position on climate change is simply disastrous. And his constant attacks on the fake media undermine democracy.”

Most Unitarian Universalists don’t like Donald Trump, but rarely do we speak about why he is a spiritual danger; mostly we focus on why he’s a political danger. I’m obviously not an evangelical Christian, and therefore not the target audience for Sider’s book or his remarks, but I think this summary of Trump as a spiritual danger is spot-on.

Another interesting point Sider makes in this interview is in response to the question of why white evangelicals supported Trump so strongly in 2016. A part of Sider’s response is particularly relevant to Unitarian Universalism:

“It’s partly because, let’s be honest, there’s a left wing fundamentalism as well as the right wing fundamentalism. And there’s a part of the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which is really, I think, hostile to Christianity and certainly to evangelicalism. White evangelicals feel that, and don’t like it.”

This describes too many Unitarian Universalists: we can indeed come across as left wing fundamentalists who refuse to acknowledge that intelligent people can disagree with us on religious issues. For example, there are Unitarian Universalists who are convinced that global climate change is one of the top two or three most pressing issues facing humanity, who claim they’ll do everything they can to arrest global climate change, yet who are condescending and dismissive when they hear the term “creation care.”

There is no doubt that Donald Trump represents a pressing spiritual danger: he’s a liar, a racist, a misogynist, and he’s going to let the world go up in flames. It would be wise for us Unitarian Universalists to figure out how we can work effectively with all those who want to stop this clear and present spiritual danger.