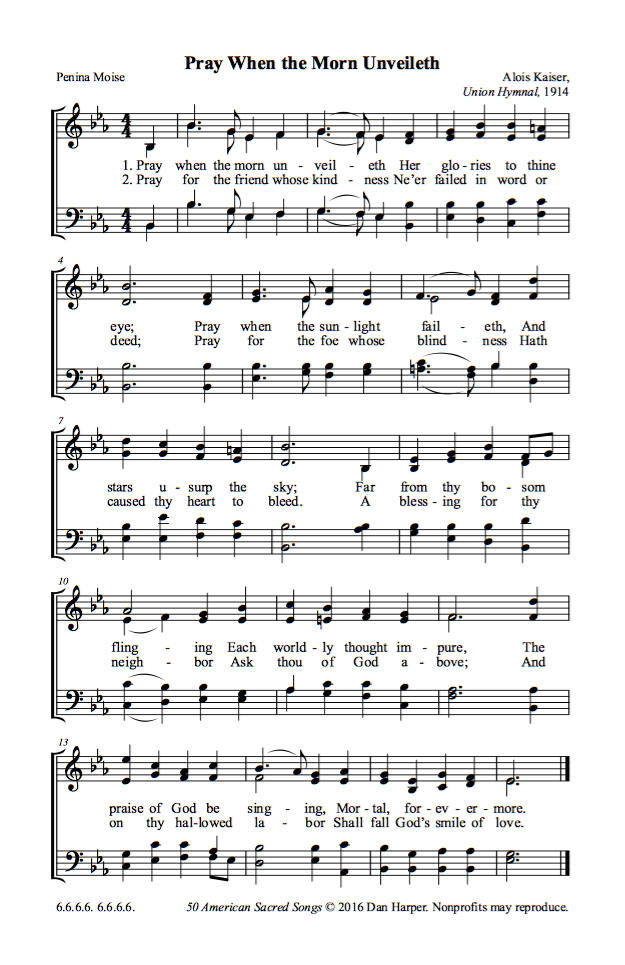

The appealing imagery of natural beauty in the first stanza of this hymn text draws you in right away, and sets you up for the social and ethical implications of the second verse. Penina Moise, who wrote the text, was a Sephardic Jew born in Charleston, North Carolina, in 1797; she lived her entire life in Charleston, dying there in 1880 (Marion Ann Taylor, Heather E. Weir, Let Her Speak for Herself [Baylor University Press, 2006], 194). Her congregation, Beth Elohim in Charleston, published her hymnal in 1842, “the first hymnal written by an American Jew”; and her hymns continued to be sung long after her death, so that the Reform Jewish hymnal of the 1960s contained more hymns by Moise than by any other Jewish author (Colleen McDannell, ed., Religions of the United States in Practice, vol. 1 [Princeton Univ., 2001], 108 ff.). She is considered to be the first American Jewish woman to write poetry of note in the United States (Solomon Breitbard, “Penina Moise, Southern Jeiwsh Poetess,” ed. Samuel Proctor, Louis Schmier, Malcolm H. Stern, Jews of the South

[Mercer University Press, 1984], 32 ff.).

This setting of Moise’s text comes from the Union Hymnal of 1914. The music is by Alois Kaiser (1840-1908), who was born in Hungary and emigrated to the U.S. in 1866. He was an important early U.S. cantor, and a prolific composer.

Pray When the Morn Unveileth (PDF, sized for order of service insert, 5-1/2 x 8-1/2 in.)

The tune is typical of late 19th century American hymnody, which may not appeal to all tastes; and the melody has perhaps too wide a range for a congregational hymn (an octave and a fourth, as bad as “The Star Spangled Banner”). But the music is well-crafted, providing a pleasant setting for the text, and I thought it worth including here: even if it is never sung by congregations, it would make a nice choir anthem.

Click here for permissions and more about the 50 American Sacred Songs project.