Chris, with Carolyn’s help, had his annual pysanky workshop today. A pysanka (plural: pysanky) is an Easter egg decorated in the Ukranian style, using wax resists and multiple dye baths. Carol and I haven’t been able to go for a few years, and it was a pleasure to be able to make pysanky once again this year.

Category: Art and religion

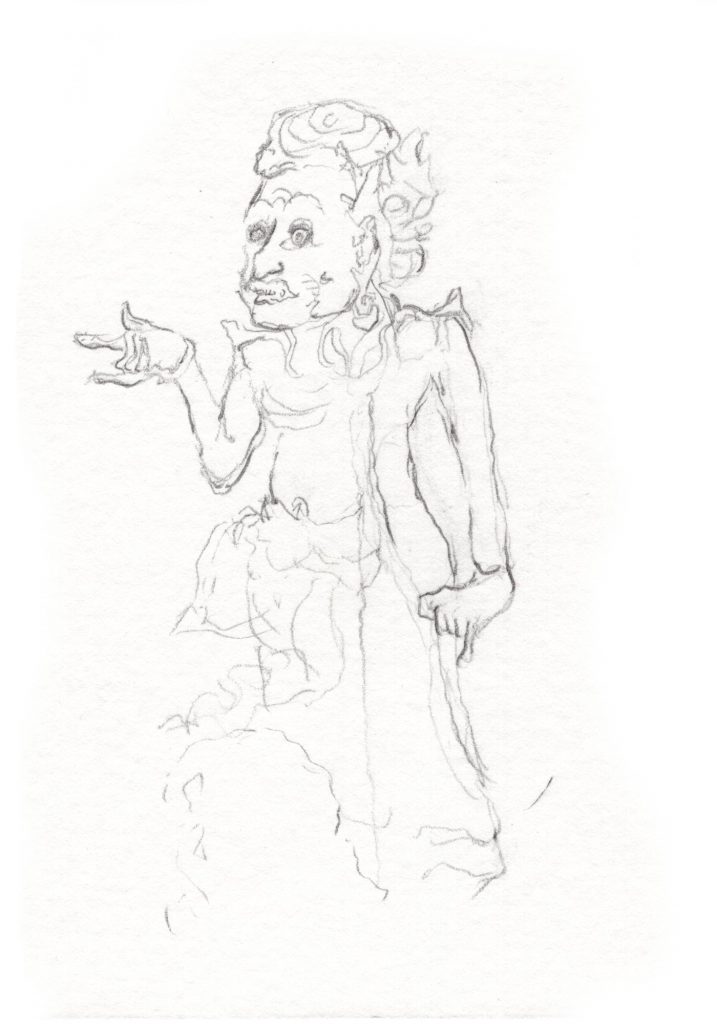

Agni

Agni, the ancient Vedic deity of fire, has always appealed to me. But until today, I’d only met Agni through poetry, like this hymn to Agni, the fifth hymn of the third book of the Rig Veda, as translated by Ralph Griffith:

Agni who shines against the Dawns is wakened;

the holy Singer who precedes the sages:

With far-spread luster, kindled by the pious,

the Priest has thrown both gates of darkness open.

Agni has waxed mighty by songs of praise,

to be adored with hymns of those who praise him.

Loving the varied shows of holy Order

at the first flush of dawn, he shines as envoy.

Midst mortal’s homes, Agni has been established,

fulfilling with the Law; Friend, germ of waters.

Loved and adored, the height he has ascended;

the Singer, object of our invocations.

Thus I was pleased to finally see a visual depiction of Agni at the Asian Art Museum this afternoon. He was part of a painting from the Ramayana, protecting Sita during her trial by fire, as imagined by a Balinese artist c. 1850-1900. Since this was a traveling exhibit, photography was not permitted, so I drew a quick sketch of Agni — leaving out Sita, Rama, the army of monkeys, the tongues of fire, and everything else in this detailed painting:

Music for democracy

How do we get rid of the rancor and hatred that was stirred up by the recent presidential election, and rebuild democracy?

How about with music? Here are four examples, in chronological order:

1. Sing with Ocupella Nov. 30: Their announcement reads: “In response to the election results and ongoing turmoil, Ocupella and other singers are creating a public musical gathering for those who want to act in a positive and powerful way in response to the new era in our country. The long and noble tradition of song fueling social movements lives on, and will live on. We hope you will want to be part of it. Our next ‘Singing For Us All’ will be Wednesday evening, November 30, 4:45-6 PM at Ashby BART. ALL VOICES ARE WELCOME! Lyrics provided.”

2. Sing with Michèle Dec. 2: Michèle writes: “I’m hosting a special post-election #MeetupAmerica gathering this Friday, December 2, at St. Alban’s Episcopal Church on Washington at Curtis, in Albany. The idea behind #MeetupAmerica is, ‘No matter how you feel about the election outcome, we can all agree that democracy works best when we don’t just post online but come together face-to-face… Don’t underestimate the power of community.’ Come with a list of your fears, hopes and present joys. We’ll share our lists and sing, at the very least, This Little Light of Mine. Children are absolutely welcome. We’ll start at 7 p.m. and end the structured part of the evening before 8 p.m. The sanctuary is ours until 8:30 p.m…..” Let Michele know if you’re going to attend; there’s contact info on her Web site.

3. Sing for Democracy Dec. 4: This is the group I’m helping to organize, and here’s our announcement:

Join us for a song circle Sunday, December 4, from 2 to 4 p.m. on the 1st Sunday of the month at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto. We welcome all singers, as well as guitars, ukuleles, banjos, and any other instrument that goes well with singing.

Why we sing together:

— After the rancorous and divisive 2016 election, some of us felt a need for more music, and more community, in our lives

— We wanted to bring together several musical communities

— You can never have enough singing

What we sing:

We’re kinda making this up as we go along, but here’s what we have so far:

— We’ll have copies of the “Rise Up Singing” songbook

— You can bring your own songs to share — bring a dozen lyrics sheets or lead sheets, or teach simple songs by ear

— We’ll go around the circle, each in turn choosing a song to lead

4. Inauguration Eve concert Jan. 19: Bruce is arranging a concert the night before the presidential inauguration. He’s working on an interfaith gospel choir, a gay men’s chorus, and music from several different faith communities. I brought Bruce’s idea to Multifaith Voices for Peace and Justice tonight (thanks to Kristi), and they’re going to see if they can add their support.

So this raises a question:

How are YOU using the arts to resist hatred and build democracy?

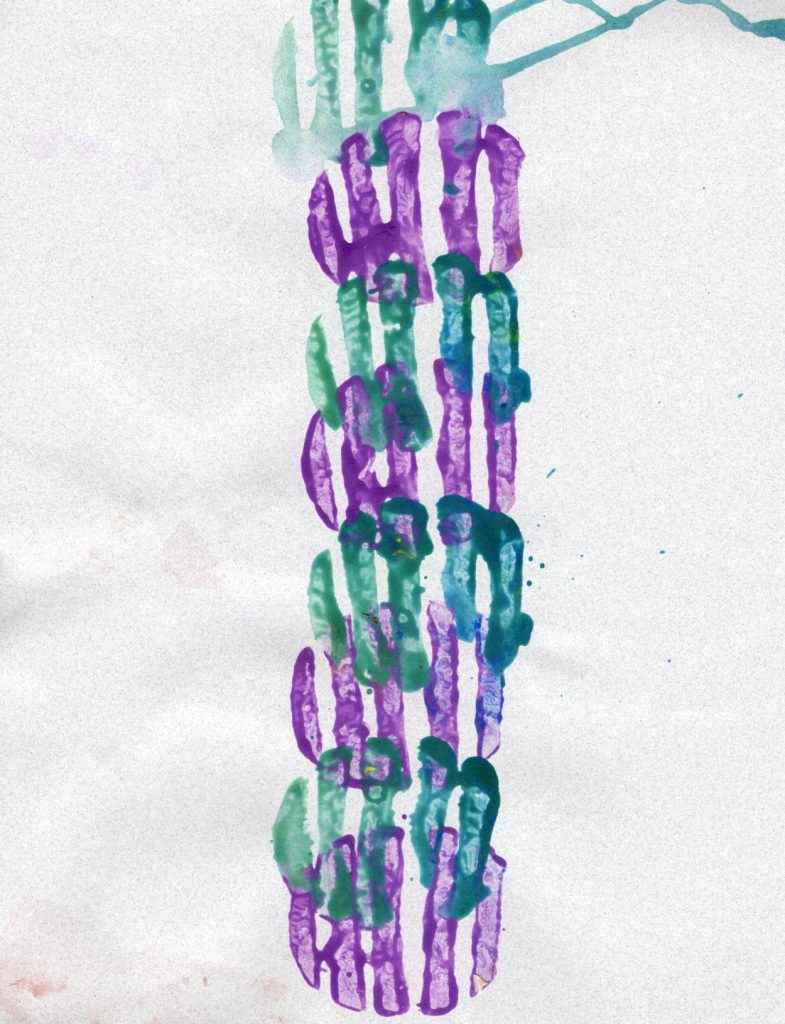

Process art: veggie printmaking

For summer Sunday school today, I wanted to do some process art. (In process art, you have fun with the process and don’t worry about the final product.) I decided to do veggie printmaking, using cut vegetables dipped in thick paint to make prints. One of the children today said it’s like stamping, except you use veggies instead of rubber stamps.

In the end, 14 children showed up, ranging in age from 3 to 13. It was a little challenging to keep the three preschoolers supplied with paint and veggies, although ultimately some of them stuck with it longer than the big kids. For paint, I bought a ten-pack of Crayola Washable Kid’s Paint. It’s thick enough to use for this project. The children liked some of the colors better than others. The dark blue and the light blue were especially vivid and fun to print with, and today we used up most of each of those 2 oz. bottles.

For veggies, I had a 5 lb. bag of potatoes, 3 apples, 4 carrots, 2 stalks of celery, and an eggplant. We used almost all the veggies today. I also had blunt-tipped serrated steak knives that the big kids could use to cut designs into the apples and potatoes. Some of the big kids tried elaborate designs like hearts and stars, but a third grader made the design I liked best: simple stripes:

The apples proved to be a lot of fun to print with. They were pretty juicy, so they diluted the paint. Some of the children loaded them up with paint, and then rubbed them around on the paper. Here’s a print where a child did just that:

Another fun thing to do was to use the serrated knife to cut a potato in half. This leaves a textured surface, which makes really interesting images:

Printmaking lasted about thirty minutes, and then we transitioned into a game of tag. Most of the prints were pretty forgettable, and most of the children did not bother to take their prints home. Of course, that was the point: the fun was in the process.

Saco, Maine

Saco, Maine

Printmaking with a steamroller, at the Ferry Beach Religious Education Conference.

Isis

Isis is a well-known Egyptian goddess who needs little introduction. This beautiful little sculpture of Isis dates from a period when the Romans ruled Egypt; so Isis is wearing an Egyptian headdress, but she’s also wearing Roman clothing.

Above: Isis with sistrum, from Roman Imperial period, c. 100 BCE to 200 CE; bronze. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, accession no. 04.1713.

She is shaking a sistrum, an small percussion instrument that was used almost exclusively by women. Kara Cooney, a professor of Egyptian art and architecture, interprets the sistrum in terms of sexuality: “The sistrum was a kind of rattle — a wooden handle supporting bars of metal, each piercing small rings that clanged together when the instrument was vibrated. The sistrum itself represented human sexuality — round objects penetrated by a phallic rod holding them in place” (1). This interpretation could be accurate, but it could be overly influenced by Freud and Co., and therefore anachronistic.

The archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley offers another interpretation; she says the sistrum, which “was played only by women,” was “a rather large loop-shaped rattle with a long handle, often featuring the head of Hathor [another Egyptian goddess], which had initially represented the papyrus reeds of the Nile Delta where, mythology decreed, Hathor had been forced to hide with her young son. Eventually the sistrum lost all trace of its original meaning and instead started to serve as a religious symbol for life itself. It consequently become absorbed by other deities, and was particularly identified with the cult of Isis at the end of the Dynastic period.” (2) And this sculpture in fact does date from the end of the Dynastic period, the time when Isis had taken over the sistrum form Hathor.

Thus in this sculpture, we see the goddess Isis at the end of some three millennia of change and development. She is wearing the flowing robes of Rome rather than the simple sheath dress of Dynastic Egypt. She wears a headdress that identifies her as Isis, though it is not the older stepped headdress of Isis seen in sculptures from 500 years earlier (see, e.g., the sculpture of Isis below, from c. 685-525 BCE). And she has taken over the sistrum from Hathor and other goddesses.

Although their adherents may say otherwise, art and material culture does not show gods and goddesses as unchanging and fixed; instead, they grow and evolve over time.

Above: Isis mourning Osiris, from Dynasty 26, c. 685-525 BCE; wood. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, accession no. 72.4172.

Notes:

(1) Kara Cooney, The Woman Who Would Be King (New York: Broadway Books, 2014), p. 39.

(2) Joyce Tyldesley, Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt (London: Penguin, 1994), p. 139.

Taweret

Taweret is one of the deities who was a fairly common presence in ancient Egyptian households. Sculptures of Taweret have the head of a hippopotamus and the body of a female human being, and the arms and legs of a lion (note 1); though of course the physical manifestations of ancient Egyptian deities were not thought to adequately represent the actual deity. Sculptures of her “held the attribute of the sa [an ancient Egyptian symbol of magical protection] in her hands and sometimes also the ankh or a torch, the flame of which was supposed to expel typhonic forces” (note 2).

A statue of Taweret would typically stand in a niche in a house, with perhaps an offering table. A Taweret sculpture might also be placed in bedrooms, to prevent sleeping humans from being assaulted by demons or ghosts. According to some accounts, she was married to the god Seth (note 3).

Below is a fine tiny sculpture of Taweret, made of faience sometime in Dynasties 26-30, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (accession number 64.2252). She is holding the sa, and you can see her hippo head, human body, and lion limbs. She is fearsome enough to give you a measure of assurance that she will indeed protect you, as a household god should; but she also appears friendly enough that I would not mind having her in my household.

Notes:

1. Garry J. Shaw, The Egyptian Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends (Thames and Hudson, 2014), p. 155.

2. Manfred Lurker, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt [Thames and Hudson, 1980/2006], English language edition of Gotter und Symbole der Alten Agypter, rev. and enlarged by Peter A. Clayton, p. 119.

3. Shaw, pp. 152, 158, 55.

Aphrodite

Aprhodite’s nature and deeds are well enough known that they don’t need to be repeated here. This head of Aphrodite, carved between 300 and 300 BCE, is sometimes called the “Bartlett Head.” It was once attached to a complete figure, and likely would have been part of a temple; many Greek sculptures from this era were painted. Now the temple and the rest of the figure are lost, and this isolated head is on display in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. It is worth remembering that when we see religious art in museums, what we are seeing has been removed from its original religious setting and purpose, and put into a completely secular context where it has no purpose except to be gazed at for its presumed artistic beauty.

Ma-ku

Ma-ku is a Taoist deity of longevity. In the image below, she can be identified by her hoe and a basket of the fungus of immortality. This Ching dynasty porcelain presentation dish was made sometime in the eighteenth century, and is now in the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (accession no. B60P376):

Today in the West, Ma-ku’s name is sometimes translated as “Hemp Maiden,” which has led a number of Westerners to misappropriate her as the patron deity of pot smokers; you can find plenty of Web sites that state this as an absolute fact. Note, however, the iconography of Ma-ku often shows her, not with marijuana, but with a basket of the fungus of immortality. And so, not surprisingly, other Western writers have jumped to the conclusion that Ma-ku is not the goddess of marijuana, but rather the goddess of psychoactive mushrooms. Obviously, psychoactive mushrooms do not produce longevity, but we Westerners do love to superimpose our own meanings on the gods and goddesses of other times and other cultures.

Rather than imposing Western values on Ma-ku, I’m more interested in learning her role and place in Chinese culture. I found it difficult to locate good solid information about Ma-ku in English. But Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany (1899), though not a scholarly work and probably biased by a colonial outlook, has a useful entry on Ma-ku under the general heading of Gods and Goddesses:

MA KU

Ma Ku: A Taoist immortalised female saint or Hsien Nu; a portrait of Ma Ku is very popular as an emblem of longevity, and is one of the very best presents a person can make to his superiors on the occasion of a birthday feast.

During my stay in Kuei-chou, I received several such presents, in the form of a portrait of Ma Ku with a pilgrim’s staff and a basket of flowers over her shoulder, the whole embroidered in fancy coloured silk floss, on a scarlet satin tablet some 8 or 10 feet long by about 3 feet wide.

Mayers writing of Ma Ku says that she is “One of the female celebrities of Taoist fable. She is said to have been a sister of the immortalized soothsayer Wang Feng-ping (see Wang Yuan), and like him to have been admitted into the ranks of the genii [i.e., the immortals]. It is related that once when Fang-ping revealed himself in the presence of Ts’ai Ching, whom he chose as his disciple and taught, by corporeal sublimation, to free himself from the bonds of death, the genii was accompanied by his sister Ma Ku, who appeared in the semblance of a damsel of eighteen or twenty, arrayed in gorgeous apparel, and who waited on her brother and his pupil with strange viands served in platters of gold and chrysoprase.

“The wife of Ts’ai Ching was newly delivered of a child, seeing which Ma Ku took some grains of rice and threw them on the ground, where they at once became transformed into cinnabar (the magic of the alchemists). Fang-ping seeing this exclaimed with a smile, ‘Sister, do you still indulge in child’s play?’ to which the damsel replied: ‘Since I have been our handmaid, thrice has the eastern sea become fields where the mulberry grows!’…

“Hence the Tsang Sang Chih Pien, signifying the cyclic revolutions of nature and cataclysms occurring upon the earth’s surface such as beings of immeasurable longevity alone are priveleged to witness more than once.” It is on this account that the image or portrait of Ma Ku is so highly prized by the Chinese as an emblem of extreme long life and happiness.

— William Mesny, ed., Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany: A Text Book of Notes on China and the Chinese, vol. III, (Shanghai: Shanghai Mercury, 1899), p. 286.