My Web host is having problems with a new php upgrade. Things may be a little wonky around here for a day or two. Please bear with me!

Author: Daniel Harper

ARC-5 radios

We’ve been cleaning up Dad’s condo, and I got the job of going through nearly 70 years’ worth of amateur radio gear. I found some lovely old radios, including these military surplus ARC-5 series “command sets.” I don’t know when Dad got these. He was licensed as W2YLY not long after he got out of the service; he might have gotten these while he was still finishing college, but I’m guessing he purchased these around 1950 after he got his first job (he doesn’t remember any more).

Plenty of ARC-5s are still on the air, and W1IS is helping us to find them a good home. I like to think that some day I might wind up contacting one fo Dad’s old radios.

Taweret

Taweret is one of the deities who was a fairly common presence in ancient Egyptian households. Sculptures of Taweret have the head of a hippopotamus and the body of a female human being, and the arms and legs of a lion (note 1); though of course the physical manifestations of ancient Egyptian deities were not thought to adequately represent the actual deity. Sculptures of her “held the attribute of the sa [an ancient Egyptian symbol of magical protection] in her hands and sometimes also the ankh or a torch, the flame of which was supposed to expel typhonic forces” (note 2).

A statue of Taweret would typically stand in a niche in a house, with perhaps an offering table. A Taweret sculpture might also be placed in bedrooms, to prevent sleeping humans from being assaulted by demons or ghosts. According to some accounts, she was married to the god Seth (note 3).

Below is a fine tiny sculpture of Taweret, made of faience sometime in Dynasties 26-30, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (accession number 64.2252). She is holding the sa, and you can see her hippo head, human body, and lion limbs. She is fearsome enough to give you a measure of assurance that she will indeed protect you, as a household god should; but she also appears friendly enough that I would not mind having her in my household.

Notes:

1. Garry J. Shaw, The Egyptian Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends (Thames and Hudson, 2014), p. 155.

2. Manfred Lurker, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt [Thames and Hudson, 1980/2006], English language edition of Gotter und Symbole der Alten Agypter, rev. and enlarged by Peter A. Clayton, p. 119.

3. Shaw, pp. 152, 158, 55.

Aphrodite

Aprhodite’s nature and deeds are well enough known that they don’t need to be repeated here. This head of Aphrodite, carved between 300 and 300 BCE, is sometimes called the “Bartlett Head.” It was once attached to a complete figure, and likely would have been part of a temple; many Greek sculptures from this era were painted. Now the temple and the rest of the figure are lost, and this isolated head is on display in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. It is worth remembering that when we see religious art in museums, what we are seeing has been removed from its original religious setting and purpose, and put into a completely secular context where it has no purpose except to be gazed at for its presumed artistic beauty.

Ma-ku

Ma-ku is a Taoist deity of longevity. In the image below, she can be identified by her hoe and a basket of the fungus of immortality. This Ching dynasty porcelain presentation dish was made sometime in the eighteenth century, and is now in the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (accession no. B60P376):

Today in the West, Ma-ku’s name is sometimes translated as “Hemp Maiden,” which has led a number of Westerners to misappropriate her as the patron deity of pot smokers; you can find plenty of Web sites that state this as an absolute fact. Note, however, the iconography of Ma-ku often shows her, not with marijuana, but with a basket of the fungus of immortality. And so, not surprisingly, other Western writers have jumped to the conclusion that Ma-ku is not the goddess of marijuana, but rather the goddess of psychoactive mushrooms. Obviously, psychoactive mushrooms do not produce longevity, but we Westerners do love to superimpose our own meanings on the gods and goddesses of other times and other cultures.

Rather than imposing Western values on Ma-ku, I’m more interested in learning her role and place in Chinese culture. I found it difficult to locate good solid information about Ma-ku in English. But Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany (1899), though not a scholarly work and probably biased by a colonial outlook, has a useful entry on Ma-ku under the general heading of Gods and Goddesses:

MA KU

Ma Ku: A Taoist immortalised female saint or Hsien Nu; a portrait of Ma Ku is very popular as an emblem of longevity, and is one of the very best presents a person can make to his superiors on the occasion of a birthday feast.

During my stay in Kuei-chou, I received several such presents, in the form of a portrait of Ma Ku with a pilgrim’s staff and a basket of flowers over her shoulder, the whole embroidered in fancy coloured silk floss, on a scarlet satin tablet some 8 or 10 feet long by about 3 feet wide.

Mayers writing of Ma Ku says that she is “One of the female celebrities of Taoist fable. She is said to have been a sister of the immortalized soothsayer Wang Feng-ping (see Wang Yuan), and like him to have been admitted into the ranks of the genii [i.e., the immortals]. It is related that once when Fang-ping revealed himself in the presence of Ts’ai Ching, whom he chose as his disciple and taught, by corporeal sublimation, to free himself from the bonds of death, the genii was accompanied by his sister Ma Ku, who appeared in the semblance of a damsel of eighteen or twenty, arrayed in gorgeous apparel, and who waited on her brother and his pupil with strange viands served in platters of gold and chrysoprase.

“The wife of Ts’ai Ching was newly delivered of a child, seeing which Ma Ku took some grains of rice and threw them on the ground, where they at once became transformed into cinnabar (the magic of the alchemists). Fang-ping seeing this exclaimed with a smile, ‘Sister, do you still indulge in child’s play?’ to which the damsel replied: ‘Since I have been our handmaid, thrice has the eastern sea become fields where the mulberry grows!’…

“Hence the Tsang Sang Chih Pien, signifying the cyclic revolutions of nature and cataclysms occurring upon the earth’s surface such as beings of immeasurable longevity alone are priveleged to witness more than once.” It is on this account that the image or portrait of Ma Ku is so highly prized by the Chinese as an emblem of extreme long life and happiness.

— William Mesny, ed., Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany: A Text Book of Notes on China and the Chinese, vol. III, (Shanghai: Shanghai Mercury, 1899), p. 286.

Dahwoodi Bohra mosque

Recently, a new mosque opened in Palo Alto, which is affiliated with a specific group of Shia Muslims known as Dahwoodi Bohra. I’ve been looking into Dahwoodi Bohra, and have found that it challenges some of my notions of Islam.

Dahwoodi Bohra is a branch of Isma’ili Islam, along with the better-known Druze; and Isma’ili is a branch of Shi’a Islam. Isma’ilism has Seven Pillars, instead of the more familiar Five Pillars of Islam. The Isma’ili consider the Shahadah — “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his prophet” — to be the grounding statement of all Seven Pillars, and therefore not a pillar in itself. The Seven Pillars of the Isma’ili include the familiar Salat (prayer), Zakat (charity), Sawm (fasting), and Hajj (pilgrimage). The three additional pillars are Jihad (struggle), Walayah (guardianship of the faith), and Taharah (purity). Although I usually think of Muslims performing Salat, prayer, five times a day, the Dahwoodi Bohra pray three times a day, since they perform some of the prayers at the same time.

The Dahwoodi Bohra have characteristic clothing which they may wear at religious ceremonies. The men wear a white tunic and coat, with a hat known as a topi (on Youtube, I found instructions on how to properly starch a topi here). Women typically wear head scarves, but rather than the subdued fabric I usually see Muslim women wearing, Dahwoodi Bohra headscarves tend towards the bright and spangly.

In common with other Shi’a Muslims, a major ritual is the Mourning of Muharram, which is observed in the first Islamic month; this observance is generally not performed by Sunnis. And there is much more to learn about the Dahwoodi Bohra: they have their own language; the largest number live in Gujarat, India, and Karachi, Pakistan; the women sometimes perform genital mutilation of girls, yet the men may be unaware of this; etc.

Yet learning even this little bit about the Dahwoodi Bohra has shown me the extent to which I have assumed that Sunni Muslims are normative. I should know better: every religious tradition I have started investigating has proved to be far more diverse than my original assumptions allowed for.

And here are some links to news stories on the local Dahwoodi Bohra mosque: here, here, and here. There’s not much about the congregation on Salatomatic, but for reference, their listing is here. Finally, the “official” Dahwoodi Bohra Youtube channel, which appears to be mostly audio files, is here.

“Nature, red in tooth and claw”

The old time Universalists were fond of saying that “God is love.” That statement may be true, but not in any sentimental sappy sense. Many years ago, Tennyson pointed out that he who might place trust in the belief that “God was love indeed / And love Creation’s final law” needed to remember that “Nature, red in tooth and claw … shriek’d against his creed.”

On our walk today, Abs and I saw a butterfly that had lost much of its left hindwing, and a part of its left forewing. We speculated that perhaps a bird or other predator had attacked the butterfly, and somehow it had gotten away, and was still flying:

Living things need to eat, and as often as not they eat other living things in order to stay alive. And this is true of you, too, O human being who think yourself an apex predator: there are plenty of microorganisms and parasites and biting insects who feed on you.

Photographing butterflies

I took a break from curriculum development on Tuesday and drove down to Pinnacles National Park. Of course I looked at the incredible rock formations for which the park is famous. But as spectacular as the scenery was, the highlight of the trip was watching butterflies in Bear Gulch. In particular, I spent about ten minutes watching one Western Tiger Swallowtail visiting larkspur blossoms. I took a great many photographs of this one butterfly, getting as close as I could. With a photograph, you can capture narrow slices of time: the position the butterfly’s wings take as it balances on a flower; the way it clings to the flower with its legs and arches its head towards a blossom; the moment when the butterfly is just approaching the flower:

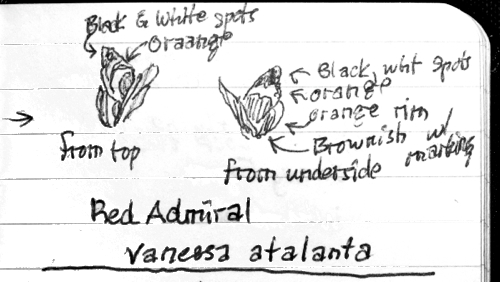

But sometimes what sticks in your memory is not what you actually saw, but the photographs of what you saw. After I left Pinnacles, I drove to Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve. When I saw butterflies there, I made a point of trying to sketch them in my field notebook rather than just photograph them, like this common butterfly:

This sketch, as an end product, is not nearly as attractive as a photograph (and I did take a photograph of this insect as well) — it’s not as attractive, but I learned more about butterflies by making this sketch. By comparing my sketch to a field guide, by seeing what I left out, I learned what I don’t see when I look at butterflies. I suspect making less attractive sketches like this does more towards sharpening my powers of observation than does taking a great many very attractive photographs.

Fast food for gulls

I spent the afternoon and early evening hiking around Pescadero Marsh. At the beach near the end of Pescadero Creek, I saw many of the same animals I saw during my last trip here: Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina): shells of the California Mussel (Mytilus californianus): the remains of Red Crabs (Cancer productus), Pacific Sand Crabs (Emerita analoga), and Eccentric Sand Dollar (Dendraster exentricus); Black Oystercatchers (Haematopus bachmani), etc.

Above: Black Oystercatchers on the rocks at Pescadero Beach

Above: The remains of a Pacific Sand Crab being eaten by unidentified smaller organisms

Walking around the marsh, I saw an even greater diversity of animals: warblers hiding in willow thickets, butterflies cruising in amongst the coastal scrub, raptors hunting over the marsh, huge nests made by wood rats. This is an area of ecotones, where several different plant communities meet one another: ocean comes up against beach; sandy beach comes up against coastal scrub; coastal scrub comes up against saltwater marsh; freshwater riparian corridor and marsh flows into saltwater marsh. I’m amazed by how many biomes, and organisms adapted to live specifically in those biomes, can be found within a short walk: I saw Arroyo Willow (Salix hinsiana) growing next to an ephemeral freshwater stream; fifteen minutes of slow walking brought me to Snowy Plovers (Charadrius alexandrius) who live and breed on sandy beaches above the high tide line.

And then there are the organisms who happily move from one biological community to another, exploiting the resources of all of them. Like gulls (Larus spp.) who fly everywhere, and eat everything. Everywhere I went, I saw gulls. As I walked north on the beach, I cam across two Western Gulls (Larus occidentalis), in beautiful fresh plumage, snacking on what remained of a Harbor Seal:

I walked up to the dead Harbor Seal to have a look; the gulls, looking grumpy, gave way to my intrusion, watching me from a safe distance. The corpse didn’t stink, but there was no longer a head, and it looked like it had been lying there for a while. I guess gulls will eat just about anything.

20 years

Twenty years ago this month, I began working as a Director of Religious Education (DRE) in a Unitarian Universalist congregation. During the recession of the early 1990s, I had been working for a carpenter/cabinet-maker, so I had been supplementing my income with part-time work as a security guard at a lumber yard. Carol, my partner, saw an advertisement for a Director of Religious Education at a nearby Unitarian Universalist church. “You could do that,” she said. So I applied for the job, and since I was the only applicant, I got it.

Above: Carol took this Polaroid photo of me sitting at my desk at my first DRE job. The computer in the left foreground is a Mac SE, and I have a lot more hair. It was a long time ago.

Over the past twenty years, I worked as a religious educator for sixteen years — full-time for six of those years, part-time for nine years — and as a full-time parish minister for four years. Since I was parish minister in a small congregation where I had often had to help out the very part-time DRE, I feel as though I’ve worked at least part-time in religious education for twenty continuous years.

Sometimes I wonder why I’ve stuck with it so long. Religious education is a low-status line of work. Educators who work with children are accorded lower status in our society, because working with children is “women’s work,” and ours is still a sexist society. And religious educators are sometimes looked down upon by schoolteachers and other educators, because we’re not “real” educators. In addition to being low-status work, religious educators get low pay, and the decline of organized religion means our pay is declining, too, mostly because our hours are being cut, or paid positions are being completely eliminated.