The creators of the Political Compass Web site assert that it is not enough to know whether a political leader is on the left or right; we also need to determine if they are authoritarian or libertarian.

Consider the economic scale first: Those on the far left believe it is best to manage the economy for the greater good of all; the further to the left, the more they believe in managing the economy. By contrast, those on the right believe to a greater or lesser degree in the power of the free market. Now consider the social scale: Those who take an authoritarian position believe that the state is more important than the individual. By contrast, those who take a libertarian view believe in the supreme value of the individual. Both scales are of equal importance.

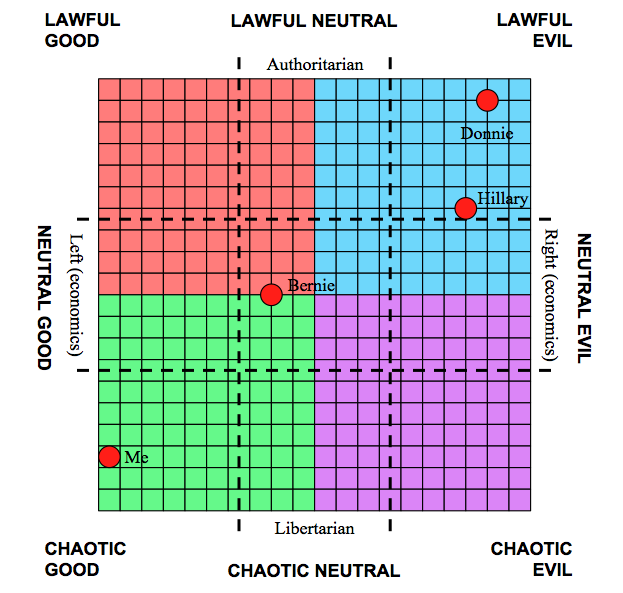

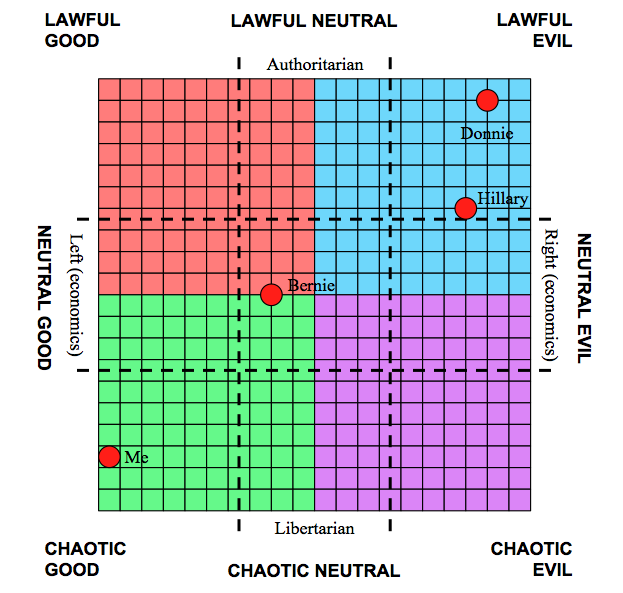

We can put these two axes together in a Cartesian coordinate system to make the “Political Compass,” where the x axis ranges from leftists (negative numbers) to rightists (positive numbers, and the y axis ranges from libertarians (negative numbers) to authoritarians (positive numbers). In this scheme, Stalin would feel at home in the upper left quadrant, which is where you’ll find those who advocate for state-controlled collectivism. Gandhi would feel at home in the lower left quadrant, with voluntary regional collectivism. Pinochet would be happy in the upper right quadrant, with overwhelming state support for the free market. Ron Paul, with his support of libertarian social ideals and the free market, falls in the lower right quadrant. And the Political Compass Web site has a quiz you can take to determine where you yourself fall along the two axes; I scored -9.6 on the economic scale, and -7.6 on the social scale, placing me in the same quadrant as Gandhi.

As much as I like the Political Compass system, I don’t think four quadrants accurately capture the way I perceive political leaders. Therefore, I like to map the Alignment System from role-playing games onto the Political Compass.

The Alignment System describes a creature or character in a role-playing game along two axes: good vs. evil, and chaotic vs. lawful. The chaotic/lawful axis maps neatly onto the libertarian/authoritarian axis of the political compass. The good/evil axis does not map so neatly. But from my perspective, the current political environment privileges either the free market or individual persons; we are given a choice between making a profit, or protecting individual persons. In the Alignment System, “Good characters and creatures protect innocent life” (link), so I choose to map the good/evil axis of the Alignment System onto the left/right axis of the Political Compass, with good corresponding to leftist.

The beauty of the Alignment System is that it offers a nuance that does not appear in the Political Compass: there is a middle ground, named Neutral, in both axes. This gives nine possible orientations, as seen on the chart below: Lawful Good, Lawful Neutral, Lawful Evil, Neutral Good, Neutral, Neutral Evil, Chaotic Good, Chaotic Neutral, and Chaotic Evil. Considered in terms of positive attributes, along the Lawful/Chaotic axis, Lawful equates with honorable; Neutral equates with practical; and Chaotic equates with independent. Along the Good/Evil axis, Good equates with humane; Neutral equates with realistic; and Evil equates with determined (link). All this helps me better understand why I feel left out of the current U.S. presidential race: there are no Chaotic Good (independent and humane) characters running for president.

Considered in terms of the Alignment System, Bernie is probably the best overall choice because he is a Neutral character, both practical and realistic: “…neutral characters … see good, evil, law, and chaos as prejudices and dangerous extremes” (link). Fair enough; but because I am a Chaotic Good character myself, I am turned off by Sanders’ claim that he is Chaotic Good when he is so obviously Neutral. If he would just admit that he is Neutral — a moderate Keynesian who is neither authoritarian nor libertarian — I could see my way to supporting him. Of course Lawful Evil characters dominate U.S. political discourse, and so Sanders will never be allowed to claim his true identity as Neutral; he will always be cast as Chaotic Good because that’s how the Lawful Evil characters perceive him.

Now both Hillary and Donnie are both in the authoritarian right quadrant of the Political Compass; i.e., they are both Lawful Evil, or in terms of positive attributes, they are honorable and determined: “Lawful evil creatures consider their alignment to be the best because it combines honor with a dedicated self-interest” (link). The only real difference between the two is that Donnie is significantly more authoritarian. However, since I am Chaotic Good, I am never going to feel comfortable with either one of them.

If you look back at previous U.S. presidential elections, as charted on the Political Compass Web site (2012, 2008, 2004), you will see that Barack Obama started out as Neutral, but after one term in office became Lawful Evil; and George W. Bush was of course Lawful Evil. The Political Compass Web site did not exist during the Bill Clinton years, but given that Hillary Clinton holds positions similar to his, it seems likely to me that Bill was also Lawful Evil. There is little doubt in my mind that Ronald Reagan was Lawful Evil, and so was George H. W. Bush. Thus we have had Lawful Evil presidents in the U.S. since at least 1980.

You know, that could explain a great deal….