In an earlier post, I published the first of a series of two sermons preached by Rev. Jacob Flint here in Cohasset in December, 1823. In these sermons, Flint proclaimed publicly that he supported the Unitarian side of the Unitarian / Trinitarian controversy then raging through eastern Massachusetts churches of the Standing Order. Not surprisingly, once their minister openly espoused Unitarianism, the Trinitarian sympathizers in the congregation left to form their own Trinitarian church.

I’m finally getting around to publishing the second sermon, the one that Flint preached in the afternoon. I can’t help wondering how the Trinitarian sympathizers responded after hearing the first sermon, the one in the morning. Did they gather together during the lunch break to talk? Did some of them refuse to return for the afternoon sermon? If they did return, were they angry as they sat there listening to their minister tell them that their cherished theological beliefs were irrational, non-Biblical, and even unchristian? And how did the Unitarian sympathizers in the congregation feel? — were they perhaps relieved that at last their minister came out and stated openly the beliefs that probably everyone in the small town of Cohasset knew he held?

It turns out to be a fairly well written sermon. Today’s Unitarian Christians might even find it to be of mild theological interest.

But I suspect most of the interest this sermon holds today is its historical interest. It’s a sermon that cause an open rupture between Unitarians and Trinitarians in one small town. It is in a sense a microcosm of the larger theological and institutional battle raging through organized religion in eastern Massachusetts. Flint was not arguing about abstract theological issues; he was arguing with people that he knew well, people he saw every day. His sermon might even cause us to reflect on the power of words and the power of thought, and how words and thought can lead to open conflict and (according to tradition) acrimony as well.

Original page breaks are noted in square brackets, like this: [p. 14]. Footnotes from the original have been numbered and placed as endnotes. A few editorial notes have been included, always enclosed in square brackets.

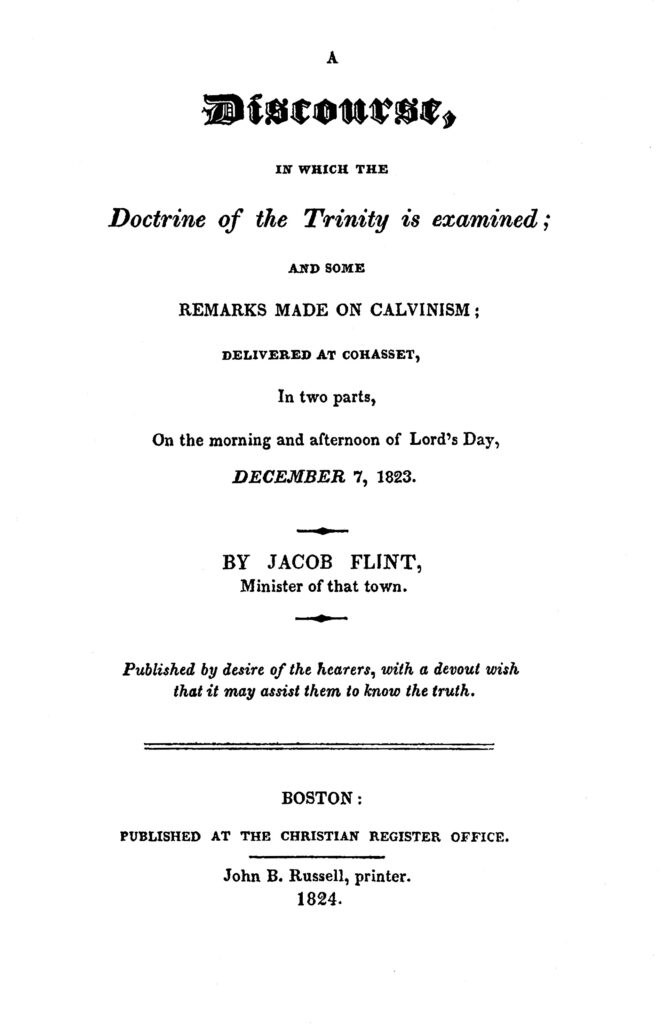

Discourse in which the Doctrine of the Trinity is examined…

by Jacob Flint (Christian Register: Boston, 1824).

[p. 11] PART II

[1] Thes[salonians] v. 21. — “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.”

The Scriptures, given by inspiration of God, contain, as I attempted to show you in the morning, a system of doctrines and morals admirable for their simplicity and truth, and a most necessary guide for men to faith, duty, and happiness. They are in the highest degree profitable for doctrine, reproof, correction, and instruction in righteousness. But I had to remark, that unhappily for the peace of society, and good will of christians towards each other, these sacred writings had not long been in the hands of fallible and and erring mortals, before they were made to teach, for doctrines, the inventions and commandments of men. These inventions, or spurious doctrines, became the source of almost endless dispute, animosity and persecution among christians. For these dreadful effects, however, there is no blame that can justly be attached to the gospel, because that every where inculcates forbearance, charity, and good will in all men.

In the other discourse, I entered on a discussion of the trinity, which the Calvinists teach their hearers to consider essential to salvation. You have attended to a form of words which from its great age and extensive use, has the best claim to be considered the Trinitarian creed; and you have found it to teach that there is God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, and that these three make but one God.

The word trinity cannot be found in the Old or New Testament; and there is not a word in any language among the tribes of men, which will express the existence of trinity in unity. The reason is, because such an existence is an impossibility in the nature of things. Professor Stuart is among the most able defenders of the trinitarian doctrine at the present day; and in his letters to Unitarians he states the question “How can three be one and one three.” His answer is — “In no way,” I necessarily and cheerfully reply. He still attempts to defend the doctrine. But he makes it only to be a distribution in the Godhead, [p. 13] and professes not to understand in what it consists.

I proceed to say, that in making Jesus, the Christ, God equal with the Father, we transgress the first of the ten commandments. “Thou shalt have no other God before, or beside me.” Considering the universal proneness of mankind to worship more Gods than one, it appears to have been a principal design of revelation to teach the unity of God, and to confine the supreme worship of Jews and Christians to the one self-existent and everliving Jehovah. And there has been no Jew, it is believed, from the time of Abraham to the present, unless an apostate from his religion, who has been a Trinitarian.

The present translation, indeed, of Isaiah’s prophecy does make him, in his prediction of the Prince of Peace, apply to this character, among other epithets, Everlasting Father — and Mighty God. Other translations of this prediction, by those who well understand the Hebrew language, have been given, in which the above epithets are made to apply, not to the Messiah, but the Supreme God. A general view of the prophetic writings will lead us to believe that their authors were all Unitarians; and we cannot believe that any one of them, by any terms he might use, intended to designate another infinite being beside Him, by whose inspiration they wrote. The prophets did not use their language with philosophical precision. They seem to delight in epithets and figures which strikingly diminish or amplify their subjects. At one time our prophet calls his nation the worm Jacob. When some of them were clothed with uncommon authority they were called Gods. Contemplating the superior power and wisdom with which the Prince of Peace was [p. 14] to appear, he might add the term Mighty, without the least intention of being understood to mean that the subject to whom he applied it was the Almighty God. The Prince of Peace was to be the father of an everlasting commonwealth. No inference, in favour of trinitarianism, can justly be drawn from the few instances where the term God is thought to be applied to Jesus Christ, and where finite beings are told to worship him. Human rulers were called Gods, and were worshipped, but not with the adoration due to the self-existent Jehovah. The voice of Herod was declared to be the voice of a God, and he was worshipped, although he was hardly good enough to be called a man.

It is said in the first chapter of St. John’s Gospel, “in the beginning was the word, and the word was God.” But the word, or Logos, as the Greeks called it, if applied at all to the Son, must be applied by a figure, the sense of whose application, must be ever doubtful. It has been rendered most probable, by authors [1] best able to investigate its meaning, that John, by the word, or Logos, meant, not Jesus the Christ, but an attribute of God, or God operating; as it is elsewhere said, by the word of God the heavens were made. Hyppollitus, an Unitarian writer of the third century, represents it as a new signification of the word Logos, to make it mean the Son, or Jesus Christ.

But whatever may have been the meaning of St John, it will, I think, be acknowledged by all, that our Lord himself understood his own nature and character better than any one else who wrote of him; and our Lord has said, in words which admit of none but a literal signification — “My Father is greater than [p. 15] I.” If the father be greater, it is evident that the Son cannot be equal with the Father, neither can he be God.

The passage in the first epistle of John, where it is said, “there are three that bear record in heaven,” is often cited in support of the trinitarian doctrine. But it is now agreed by the most able writers of the Trinitarians, as well as of their opponents that the text does not belong to the inspired writings. It is not found in any manuscript of the Gospel, written and published before the fifth century. That the text has been since inserted, without authority, is I think, made sufficiently evident from authorities cited in Ware’s letters to McLeod, letters which every one should read, who is searching for truth. And, as that author justly observes, whoever, knowing the fact above stated, shall hereafter use the 7th verse of the fifth chapter of St. John’s first epistle, as an inspired text, will be guilty of handling the word of God deceitfully.

Some good effects have resulted from controversy among learned christians. It has excited the laborious disputants to such thorough investigation of the divine authority of the Holy Scriptures as places them on a firm basis, a basis which the gates of hell can never shake. It has also enabled christians to detect and mark distinctly the few texts which have been interpolated, and others which have suffered from the number of times the Scriptures have been copied, and the different translations through which they have passed. Considering the difficulties they have had to encounter, it ought to be attributed to the peculiar care of divine providence, and be made a subject of thanksgiving, that they have been continued to us, with so few exceptions, what they were when collected [p. 16] and published, by those who had authority to determine their genuineness and truth.

It is not necessary to notice all the texts and passages of Scripture which have been thought by Trinitarians to support their creed. These passages have been explained in a manner, we think, fully consistent with the Unitarian faith. It is sufficient for us to show, that Jesus Christ did expressly declare that his father is greater than he, and consequently that he could not be God; and that the tenor of the New Testament does represent the Son, as deriving existence from his Father, appointed and sent by the father, attributing all the mighty works which he did to the power and spirit of God, operating in and by him. He always prayed, not to himself, but to his Father, and him alone he worshipped. In illustration of these remarks, the following passages may receive attention. “I do nothing of myself.” “Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is God.” When praying to his Father, he said, “This is life eternal; that they,” meaning those for whom he was praying, “might believe on thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom thou hast sent.” It is evident that Jesus meant by the only true God, the being to whom he was praying; not himself whom the only true God has sent. “There is one God and one Mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” You all know that a mediator supposes two parties between whom he mediates. But if you suppose Jesus Christ and God to be one and the same, where is the mediator? He cannot be both God and Mediator. St. Paul, speaking of the power which God committed to the Son, seems particularly to guard the Corinthians against the Trinitarian belief. “When he saith all things are put under him, it is manifest that he is excepted which did put all things under him. And when all things shall be subdued unto him, then shall the son also himself be subject unto him, that put all things under him, that God may be all in all.” I might continue to cite texts, proving the Unitarian faith, but it would swell my discourse beyond your [p. 17] patience. I will present you with one passage more only, which expressly proves that Christ was not equal with the Father. “Of that day and hour knoweth no man; no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.” Not even the Son knoweth when that hour shall come; yet if he were God, he must have known it.

If then the doctrine of trinity in unity be mathematically false, — if it violates the express command of God, which forbids us to have any other God before him, if it have no support from reason, and is not taught in the sacred Scriptures, — ought it not to be considered an error, and a spurious doctrine? But I would impress it on your minds, that by rejecting the doctrine of the trinity, we do not, as you are sometimes falsely told, reject our Saviour; no, we receive and acknowledge Jesus Christ, a Saviour as ample as the Trinitarians can possibly make him. We receive him in all the offices in which he is offered to us in the Gospel.

But if the doctrine of the trinity be a false doctrine, how came it, it may be inquired, to be originated and admitted into the church, and retained for so many centuries? A careful attention to the history of the doctrine will enable us to solve the question. was, as we think may be satisfactorily proved, formed by those christians, who had been pagan philosophers, or instructed in their philosophy. The Jewish christians it is believed had no hand in it. These philosophers having been conversant with false systems of religion, almost universally prevalent, and which taught the worship of more Gods than one, were not satisfied with the simplicity of worship taught by the Scriptures. Although they admired the christian system, generally, they had a prejudice in favour of a plurality of Gods. Seeing that Jesus the Christ had performed works which no man could do, unless God were with him, and wishing probably to exalt him above the reproach of the cross, [2] they pronounced [p. 18] him to be a God. And converting the Holy Spirit of God into a separate person, they considered him another God, and then they had three Gods. But finding the Holy Scriptures, expressly and repeatedly to forbid the worship of more Gods than one, and unyielding on this point, they said their three Gods made but one God. Thus it seems originated the doctrine of trinity in unity. Justin Martyr, who had been a disciple of Plato, was among the first who wrote in favour of the trinity. It was at length received into the church; but not without a struggle against Unitarian opposition.

The Bishop of Rome in the fourth century became head of the christian church. As successor of St. Peter, he claimed to hold the keys of heaven and hell, meaning, perhaps, the church and the world. Although the prerogatives of this officer were at times questioned by other Bishops, yet he had sufficient influence with his christian court, to receive into the church and retain in it for doctrines, whatever inventions he saw fit to sanction. The doctrine of three Gods in one was confirmed, — and the religion taught by the gospel was corrupted, till the Roman Catholic worship became nearly or quite as idolatrous as that of the heathen.

The errors in doctrine, and the superstitions of that church were guarded not by weapons which were spiritual, but by those which were carnal and deadly. The sword of physical and civil power was placed in her hand. Non-resistance and passive obedience in regard to the powers of church and state was a doctrine received by the ignorant multitude, and enforced with rigour by pontiffs and kings. Popes claimed jurisdiction at length, over kings and their subjects, souls and bodies, throughout christendom ; and for a number of centuries not a tongue could suggest a doubt as to the infallibility of the sovereign pontiff, or question the truth of any invention he chose to sanction, without rendering the body in which the tongue moved, liable to the dungeon, the rack or the burning stake. This state of things, My Brethren, [p. 19] accounts for the existence and retention in the church of the trinitarian doctrine, with other corruptions, till the reformation by Luther; an event which ought to be celebrated in every Protestant country, as a jubilee, with most hearty thanksgiving to God.

But the reformation, though glorious, was not complete. Men born blind, when their eyes are opened do not, at first, have distinct and correct vision. They see men as trees walking. [3] Luther wished to have the Scriptures purified and to speak for themselves. Calvin found the trinity and other materials, but not, I believe, his relentless decrees, in the church against which he had protested. But when he had duly arranged the articles of his creed, he would suffer no one to question the truth of any part of it. Servetus could not receive it entire; and although he might have been able to say with St. Paul — “I believe all things that are written in the law and the prophets and the gospel, and have lived in all good conscience before God until this day;” yet he was barbarously [4] punished, by Calvin that erring reformer, and caused, by a slow fire, to be burnt at the stake.

The doctrine of the trinity, with Calvin’s creed, was received generally through protestant Europe. From the abuse of ecclesiastic and civil power, which supported it, our fathers fled to this country. And although they were an association of men, pious and enlightened, far beyond the general mass of mankind, [p. 20] yet they brought with them a certain measure of the spirit of the times in which they lived, and the trinitarian doctrine of the church from which they had dissented and separated. There can, I think, be no doubt, that the church of Rome, after the reformation had an influence on the church of England, and that the church of England had influence on the faith of our fathers, when removed to this country. This influence being continued, in some degree, there I am fully persuaded, many, even learned Calvinists and Trinitarians, in this land of light, who now believe and act, though perhaps they perceive it not, from an influence descending from the church of Rome that mother and nurse of error and persecution. This, it would seem, is manifest in the views which Calvinists and some others have always entertained in regard to the Lord’s Supper. What keeps thousands of honest Christians from joining in that simple, yet divine and edifying rite, but the traditionary terrors with which it has been surrounded, descending from the papal doctrine of transubstantiation?

The system of divinity, of which the doctrine of the trinity is a part, has been entertained, in this country, with a favour, which would not, we think, have been manifested towards it, but from the fact, that it has not been generally preached or believed, except for the purposes of great excitement, in such manner as to show its wounding and terrific points. Vast numbers have received it without knowing what it is. It has been a popular tradition of the fathers, and strong motives have been held out to many learned and I believe good men, to hold it fast, although it should happen to make void the commandments of God. [5]

[p. 21] Thus I account for the existence, in the church, in this country and at this day, of the trinitarian doctrine, and the Calvinistic system connected with it. But since the dread of ecclesiastic and civil power has been removed, and Christians permitted to inquire freely for the truth, men whose talents and christian virtues adorned the church, have arisen and multiplied, whose learned research and faithful illustrations of the Holy Scriptures have brought to light the hurtful errors these sacred writings have been made to teach for doctrine, and particularly the one we are considering. The great Locke, Newton, and Price, [6] with a host of great and good Christians in Europe, have supported the Unitarian and Apostolic doctrine of one God only, and one Mediator between God and men. Nearly a century ago, there were able preachers and laymen in this country, of the Unitarian faith. Their numbers of late have been rapidly increasing. The venerable Dr. Gay of Hingham, and [John] Brown of Cohasset, have been among their number; and the christian communities in that place and this have for more than a half century past been sitting under rational, Unitarian preachers. [8]

It is from this circumstance, my hearers, that our friends in the metropolis, who assume to be Orthodox, have reported us to be without the Gospel, and in a condition but little if any better than the poor heathen. And in their great compassion for our souls, have sent among us trinitarian itinerants of various denominations, to convert us to Christianity! They have so far succeeded, I understand, as to have brought a number of the amiable lambs of this flock to confess that they hated God, the benevolent Author of their being and enjoyments. What disinterested benevolence! And let it not be thought that they have manifested this great compassion for you only; they have, I believe, shown the same kindness to every christian [p. 22] Unitarian society in New England. But I have confidence in you, My Brethren, that you will perceive their real design, — that you will put on the armour of God, and stand fast in the Apostles’ doctrine, and in the liberty, wherewith Christ has made you free.

It may be further inquired, — What evils attend a belief of the trinity? Some of the evils I will concisely point out to you; and they are shocking to enlightened piety. In the first place, a belief of three Gods in one, distracts the mind of him, who would worship one God, as commanded, in spirit and truth. If the worshipper, engaged in his devotion, have in his mind three beings, each of whom has an equal claim to his adoration, how can he tell to which he should give it; and if he divide his thoughts, he cannot worship One God with his whole heart. It is evidently impossible to think of three beings and only one at the same time. As we would honour the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the authority by which the Son acted, we should indeed honour the Son, as the greatest benefactor the world ever saw; but not with the adoration due only to the former, as the self existent and everliving Jehovah.

Again. If you believe that Jesus the Christ is God, then you must believe that God was born of a woman, was subject to human infirmities, and died on the cross. Trinitarians I am sensible do not pretend to believe this; but it is a consequence which will follow from their faith; because Jesus Christ was born, did suffer and die. [7] And the infant God, — the blood of God, — and God rising from the tomb — are trinitarian expressions; but at the thought of which the soul must revolt with [p. 23] horror in him, who believes that God is self-existent, and incapable of suffering or change.

Another evil attending the system of faith containing the trinity is, that it is made an instrument of delusion to the amiable, but necessarily uninformed part of society, giving false terrors and hopes, and thereby a powerful inducement to believe and hold fast what is not true. Those who claim to be exclusively orthodox hold up the idea that all must suffer forever who do not believe the trinity, original sin, total depravity, and the necessity of irresistible regeneration by the spirit of God. You will find, either at the head or heel of their form of doctrines, something like the preface to the creed of Athanasius. He who doth not hold this faith whole and entire must without doubt perish everlastingly. And who, that is simple enough to believe Athanasius, Calvin, or any of their followers had authority to say this, would not believe any thing, to escape everlasting torment, and secure endless happiness; especially, when from strong excitement, he believed himself wrought upon by the spirit of God. But a moment’s reflection should teach every one that a mere human maker or preacher of a creed, unless it be in the undoubted words of inspiration, has no more right or authority to doom a fellow creature for not believing it, than another fallible creature has to doom him if he do believe it.

Finally. Let it not be thought, from any thing I have said, that I deem a scriptural, rational and strong faith of small importance. It is of vast moment to you and myself. But let me intreat you to receive the articles of your faith, not from the inventions of erring men, but from the plain dictates of God’s word; and keep it always in your minds that faith without works is dead. By good works, as the fruits of faith, you are to know yourselves, and be known by others. If conscious of harbouring sinful affections and dispositions, and that you allow yourselves to be guilty of personal transgressions. you must, to be happy in the favour [p. 24] of God, repent and reform. God has declared that his grace is sufficient for you. Ask and ye will always receive as much and so much only of divine assistance in duty, as is consistent with the free exercise of your moral powers. When that is destroyed, by direct and irresistible influence of the spirit of God, there can be justly attributed to the man, it would seem, neither praise nor blame, virtue nor vice, in being turned one way or another, any more than to the material wheel, which by an extraneous power is turned on its axis.

Without holiness you are told no man can see the Lord. While you believe, remember that holiness consists more in doing the things that are lawful and right, than in the fulness of faith and feeling. Devils, it is said, believe, and feel, and tremble; but they have no holiness, or christian virtues. Could your faith remove mountains, and your feeling dispose you to give your bodies to be burned, and have not charity and the other christian virtues, you are nothing better than sounding brass or tinkling cymbals. “Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom of heaven, but he that doeth the will of my Father who is in heaven.” His will is that we discharge with diligence and fidelity the duties of this world while in it, thinking and acting at the same time with a wise reference to a future, infinitely more important to us than the present. But to denounce, as criminal the lawful employments and innocent pleasures of society, and to practise in seclusion vain repetitions of devotion, like the hermit of the cave or the monk of the cloister, is no part of christian duty. He who sincerely loves his God, his Saviour, and his fellow men, performing with upright intentions, his religious services at the times and places only appointed by heaven, and at the same time does the most good to himself and to society, will for ever be the most acceptable to his God and Judge.

Notes

[1] Priestly and others. [Joseph Priestley, who espoused Unitarianism, and even started a Unitarian congregation in America after he left England.]

[2] It was to the Greeks foolishness.

[3] It would, we think, be honorary to the sympathies of Calvin, to consider him as having viewed with his mental eye, men like trees walking, without moral or any other similitude — which come forth and grow in size and form precisely as their maker intended and caused them to do, and the greater part of them purposely for the fire. Calvin, it will be acknowledged, saw through a glass darkly.

[4] I do not exhibit this spirit of Calvin, as a spirit common to those who believe his creed. Very great have been the numbers of that denomination who have exhibited a truly christian and benevolent spirit, and who have been extensive benefactors to society. But they have been made so, it is believed, not from the peculiarities of their creed, but from the great and genuine truths of the gospel which they have believed and practised in common with Unitarian and rational Christians.

[5] Any one may see that all commandments must be void, which are made to beings who have no power to obey them. And I would ask some of my brethren, who hold the Calvinistic tradition with the firmest grasp, to learn of themselves, whether they do not, by this tradition, make void that command of God, which is next to the first, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

[6] Dr Watts, it appears, after writing his Psalms and Hymns, changed his opinions, in regard to the trinity; “his last thoughts were Unitarian.” — Lardner. [Rev. Andrew Pakula, former minister a New Unity, a Unitarian congregation in North London, said there was a tradition that Watts owned a pew in that church late in life.]

[7] The Scriptures do not, as I can learn, speak of any part of the person or being whom they designate by Jesus Christ, — the true Messiah, the Son of God, — which was not born with him, and did not suffer in him. If another part or being, which did not and could not suffer in him, be joined to him and made to constitute his person or being, it must be without Scripture authority, — a mere fiction of man’s invention.

[8] [Editorial note: Rev. Ebeneezer Gay served as minister at Old Ship church in Hingham from 1717-1787. John Brown served as minister in Cohasset from 1747-1791. Both these preachers were called Unitarians by John Adams, himself a Unitarian who knew both men; in a letter dated 1 May 1815, Adams said that circa 1755, “Rev. Mr. Shute of (Second Parish in) Hingham, Rev. John Brown of Cohasset, and, perhaps equal to all, if not above all, Rev. Dr. Gay, of (Old Ship in) Hingham, were Unitarians.”]