Back in 1823, Rev. Jacob Flint was the minister of the one church that then existed in Cohasset, Mass. He had been ordained in Cohasset in 1798. He was fairly liberal to begin with, but over the quarter of a century he served the congregation he had become an outright Unitarian. So on December 7, Flint decided to preach a sermon on Unitarianism.

I can imagine the scene. He preached this sermon in the Meetinghouse that we still use today, but the old box pews were still in use in 1823. Wood stoves had been put in the Meetinghouse for the first time the previous year, in 1822, so at least people would have been relatively warm for the two lengthy sermons that were delivered each week. Flint would have climbed up into the high pulpit, suspended halfway between the main floor and the gallery. Sadly, he was not a good speaker — John Adams wrote that “his elocution is so languid and drawling that it does great injustice to his composition” (John Adams, Diary, 19 Sept. 1830).

Despite his poor elocution, at least some people in the congregation must have been paying close attention to this day-long Unitarian sermon. Within months the Trinitarians had left in a body to start building their own church just a hundred feet away across the town common. I can just imagine how angry the Trinitarians were after the morning service on December 7, 1823, and how little they looked forward to the second sermon in the afternoon when they would hear even more about how wrong the doctrine of the Trinity was. How they must have steamed and stewed as Flint preached, especially since his preaching seems specially designed to infuriate anyone with Trinitarian leanings.

But this was probably to be expected of Flint, who was an uncompromising man. Years later, Capt. Charles Tyng remembered a time from his boyhood when he had to live in Flint’s house:

“…I was then put under the charge of the Rev. Dr. Jacob Flint, the minister at Cohasset. I soon found that the change was from the frying pan to the fire. Doctor Flint was a large man with a forbidding countenance. He was morose & cross in his family, which consisted of his wife, three sons, and an infant daughter…. I dreaded Sunday, the Dr. was so very strict, made us boys sit in the house, reading our Bibles, or learning hymns…. Dr. Flint was a tyrannical man, and very severe, particularly with his own children. Hardly a day passed without his whipping them. Us Boston boys did not get it so often, although I often felt the effects of the rod. He probably was deterred from whipping those who boarded with him, as his disposition would have induced him, had he not thought our parents would take us away.” (Charles Tyng, Before the Wind: The Memoir of an American Sea Captain, 1808-1833, chapter 1.)

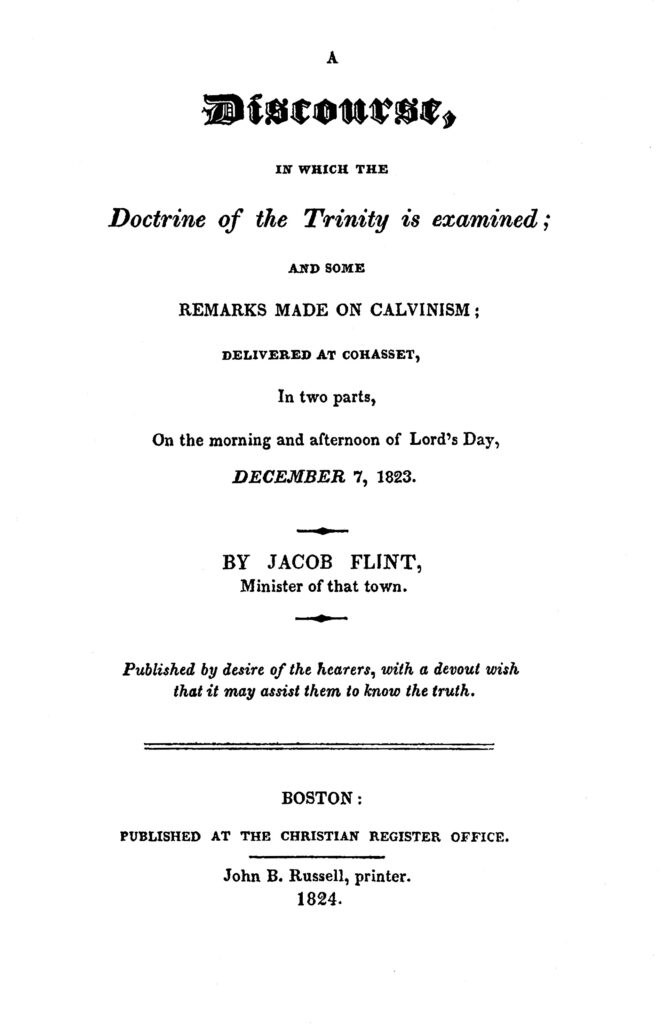

With that preface, here’s the first part of Flint’s divisive Unitarian sermon of December 7, 1823:

[p. 1]

A Discourse

in which the

Doctrine of the Trinity is examined;

and some

remarks made on Calvinism,

Delivered at Cohasset,

In two parts,

On the morning and afternoon of Lord’s Day,

December 7, 1823.

by Jacob Flint,

Minister of that town.

Published by desire of the hearers, with a devout wish

that it may assist them to know the truth.

—————

Boston:

Published at the Christian Register Office.

John B. Russell, printer.

1824.

[p. 3]

1 Thessalonians v. 21 “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.”

[Editor’s note: The printed sermon incorrectly identified this verse as 2 Thessalonians v. 21.]

When I last addressed you, my hearers, from this desk, I had at the head of my discourse the words now read. Among other things, I then remarked to you, that it had been my endeavour, since I received the charge of this church and Society, to give you rational and just views of the doctrines and requisitions of the Gospel. I remarked, also, that because I had considered practical preaching, generally, more useful than controversial; because I had preferred good practice to doubtful theory, christian virtue to speculation, I had dwelt mostly upon the great duties of life, inculcated by Christianity, and the powerful motives by which their practice is enforced; viewing it of far greater importance to you, that your hearts should be pious and benevolent and your lives holy, than that your creeds should be ample and your discernment acute in all those controverted opinions, which have so long and so much divided and vexed the christian world.

But as there seems of late to be some in this society, who have a greater fondness for doctrinal than practical [p. 4] subjects, I think it proper, for a while at least, to alter a little my manner of preaching, rendering it more speculative; as I would, in ways which are lawful and expedient, become all things to all men. — I will now, therefore, proceed, according to my purpose before mentioned, to give you a history of the more prominent opinions,[1] which have been subjects of controversy for many centuries, will prove or try them, and aim to hold fast that which is good.

The first Christian church, which existed in the world after the resurrection of our Lord, was the church at Jerusalem, consisting of the twelve apostles and seventy disciples, who had accompanied Jesus during his ministry. It was formed principally or wholly of Jews, who had been converted to Christianity. Its members had been instructed by Christ himself, as to the design of his mission, and the doctrines and principles of his religion. This, it is thought, was the most pure church, as to doctrines, feelings, and manners, that has existed. The members of it believed that Jesus was the Christ, the true Messiah predicted by the prophets; and they had seen with their eyes and heard with their ears the miracles and benevolent deeds he performed, and the precious promises he made to believers. But they believed that his being, and all the powers he possessed and manifested were derived from God his father, who had commissioned and sent him; for he had said unto them, I do nothing of myself; my doctrine is not mine, but his that sent me.

[p. 5] This church, founded by our Lord and his apostles, at Jerusalem, was the model of all those which were afterward erected, during the first century. It was governed by the apostles themselves, to whom both the elders, and those who were entrusted with the care of the poor, and the deacons were subject. The people, common Christians, though they had not abandoned the Jewish worship, held, however, separate assemblies, in which they were instructed by the apostles and elders, prayed together, celebrated the holy supper in remembrance of Christ, his death and sufferings, and the salvation offered to mankind through him. Among the virtues which distinguished the rising church, in this its infancy, that of love one to another, and charity to the poor and needy, shone in the first rank, and with the brightest lustre.”[2]

In this,— the mother of all other christian churches during the first hundred years,— there was a most engaging simplicity in doctrines, in faith, discipline, virtues, and hopes. We find in it nothing of trinity in unity,— no imputation of Adam’s guilt to his posterity, and their consequent total depravity and moral inability,— nothing of unconditional election to eternal life, and reprobation to everlasting misery, without regard to moral worth. At this period it does not appear, that there was a Christian on earth, who believed that Jesus Christ was God, equal with the everlasting God, unless we infer it from a doubtful passage in St John’s Gospel, or a few still more doubtful ones in the apostolic epistles, afterwards written, and which [p.6] contain, it is believed, ten-fold more, which clearly assert and imply that Christ was not God, but a finite being, who derived all his extraordinary powers from the self-existent Jehovah, his father. The books of the New Testament were not collected and published till about the middle of the second century.

The apostles having by miracles and wonders, which God wrought by them, spread the Christian religion through the vast Roman empire, were not permitted to continue, by reason of death. Inspiration and miracles ceased. The gift of tongues ceased. Christians had no longer infallible human guides,— though many, in every age, have made false pretensions to infallibility. The Bible, or books contained in the Old and New Testaments, which all Christians considered, and do now consider, as inspired writings, was the only infallible guide to truth, teaching men all that is necessary for them to believe and do, to obtain the favour of God and salvation.

But these writings, in the hands of the christian clergy, and with only the blessing of divine providence on their labours, had to encounter various difficulties. They had to encounter and, if possible, to overcome the bigotry of the Jews, strongly attached to their own system, and ever trying to mingle their ceremonies with the simplicity and pure worship taught by the gospel. The supposed clashing between the law and the gospel, which ought to have been restricted to the law of Moses, occasioned a disunion and sharp contention between two of the apostles. [3] One supposing that faith, with its proper influence, was sufficient to [p. 7] salvation without the works of the law,— the law of Moses; the other, blending the immutable moral law with the law of ceremonies, declares that faith without the works of the law is dead. St Paul, we find, employs a considerable portion of his epistles to the Romans, Galatians, and Ephesians, among whom were many Jews, in combatting this Jewish attachment to the ceremonial law, circumcision, &c. Hence some christian teachers, after a while, probably considering St Paul as speaking of the moral law instead of the ceremonial, began, and their sermons have continued to the present day, to denounce all works of the law of God,— to delay all good works,— and to hold them, in regard to salvation, no better than wicked works. And it is now often asserted by Calvinistic and Hopkinsian teachers, that a man of a good moral character is no more likely to be saved than the most licentious and profligate villain. But this sentiment, as I hope hereafter to show you, is as far from the apostle’s sentiment, as the poles are asunder. Shall we sin, said he, that grace may abound? God forbid.

The gospel, again, had to meet and come in contact with the subtle but absurd systems of heathen philosophy; and the early, simple, and salutary doctrines and principles of the gospel, it is acknowledged by all who are acquainted with the early progress of Christianity, were warped and corrupted, that they might meet the views of the disciples of those pagan systems. Converts were made of the heathen, and of those very philosophers, who brought into the church an unyielding attachment to their own learned, yet absurd and false schemes of religion and morals; and they made use of all their wit and sophistry to make the [p. 8] Scriptures favour and countenance their wild schemes. will easily be imagined, says an approved historian, [4] that unity and peace could not long reign in the Christian church, since it was composed of Jews and Gentiles, who regarded each other with the bitterest aversion. As the converts to Christianity, those pagan philosophers could not extirpate radically the prejudices which had been formed in their minds by education, and confirmed by time, they brought with them into the bosom of the church, more or less of the errors of their former religions.” These errors were perpetuated in the Christian church. Thus were the seeds of discord and controversy early sown, and about points in doctrines, supported neither by enlightened reason, nor by a fair and connected view of the Holy Scriptures. Of these errors, especially that of the trinity, Unitarians were the strenuous opposers, and Trinitarians the more numerous advocates. This state of things continued in the church, till all errors and false doctrines, which had crept in were confirmed by the Church of Rome,— all opposition silenced,— and a dreary night of intellectual and moral darkness reigned, till the reformation by Luther.

What we believe to be the more prominent of these errors and corruptions, some of which still continue to interrupt the harmony of Christians, I will now proceed more particularly to describe and point out to you; and will begin with that which makes our Lord Jesus Christ to be God,— equal to the self-existent and everliving God. This is one article in the Calvinistic and Hopkinsian system of divinity as [p. 9] taught at the present day; and those who hold to it are called Trinitarians, because they contend that there are three Gods in one God. Those who hold that Jesus Christ is not God, but the one finite Mediator between God and men, are called Unitarians; because they believe with the apostle in the unity of God; that there is one God only, of whom, and to whom, and through whom are all things; and that he commissioned his son Jesus Christ, to declare his will to men, to preach repentance for the remission of sins, to die on the cross that he might reconcile men unto God, and to rise from the dead that he might give to all men a sure and certain hope of resurrection to eternal life. There are, indeed, among Unitarians, some shades of difference in opinion respecting the question of the pre-existence of our Saviour. But all agree that he is not God, equal with the Father; and that the doctrine which makes him so is against reason and unscriptural. Among Trinitarians there seems to be no difference of opinion on this point, that Jesus Christ is God, and that there are three Gods in one God.

At different periods of the church, Trinitarians have put their belief into certain forms of words called Creeds. That which has been adopted by the Roman Church and the Church of England, and against which the Trinitarians at this day, I believe do not object, is one which was formed by Athanasius.

That you may have a fair view of the doctrine in question, I will recite to you, with its preface, the essential parts of this creed in its own words, and it is what follows. “Whoever will be saved, before all things it is necessarry that he hold the Catholic faith; [p.10] which faith except every one do keep whole and undefiled without doubt he will perish everlastingly. And the Catholic faith is this;—

“That we worship one God in trinity, and trinity in unity; neither confounding the persons, nor dividing the substance; for there is one person of the Father, another of the Son, and another of the Holy Ghost, but the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, is all one; the glory equal, the majesty co-eternal. Such as the Father is, such is the Son, and such is the Holy Ghost; the Father uncreate, the Son uncreate, and the Holy Ghost uncreate; the Father incomprehensible, the Son incomprehensible, and the Holy Ghost incomprehensible. The Father eternal, the Son eternal, and the Holy Ghost eternal; yet they are not three eternals but one eternal. —So likewise the Father is Almighty, the Son Almighty, and the Holy Ghost Almighty; and yet they are not three Almighties, but one Almighty. So the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Ghost is God; and yet they are not three Gods, but one God. The Father is made of none; neither created nor begotten; the Son is of the Father alone; not made nor created, but begotten. The Holy Ghost is of the father and of the Son; neither made nor created nor begotten, but proceeding. And in this trinity, none is afore or after other; none is greater or less than another; but the whole three persons are co-eternal together, and co-equal. So that in all things, as aforesaid, the unity in trinity and trinity in unity is to be worshiped.” [5]

Rejoicing as we all do, in the light and freedom which Protestant christians now enjoy, you will wonder, I presume, with some degree of astonishment that this creed was ever admitted into the christian church. Yet this, or the doctrine said to be contained in it, and which is insisted on as essential to salvation, will not, I believe, be objected to by any Calvinist, Baptist, or Methodist who has recently favoured you with his instruction. But if you have attended to the several propositions as I have recited them, you will, I think, perceive and acknowledge they contain as direct and evident contradictions as were ever put together in so many words. There is on the contrary, no inconsistency in the doctrine which teaches us to believe in one God, and one mediator between God and men, as taught by the apostle. It is intelligibly revealed by the sacred writings,— is what reason approves,— and is highly consoling to frail, and erring, but intellectual, moral and immortal creatures. Seeing it to be good, let us hold it fast.

NOTES

[1] In this and a series of discourses which the author is delivering to his people, on the Calvinistic system.

[2] Mosheim. [Johann Lorenz Mosheim (1693-1755), historian of the Christian church.]

[3] Gal. ii. 11. I withstood him to the face, because he was to be blamed.

[4] Mosheim.

[5]Common Prayer Book.