In November, British singer-songwriter Angeline Morrison released a new song titled “Jump Billy.” I got interested in the song because it tells the story of someone born in America who left during the American Revolution. If you dive into local history, you’re constantly running up against stories of the Tories who left America during the Revolution. But you rarely hear the rest of the story — where they went, and how they fared.

Here’s a link to Morrison’s studio recording of “Jump Billy” — which she has made freely available on an educational webpage about the life of William Waters.

So why did Morrison write this song? She has long loved the traditional music of the British Isles. As the daughter of a Black Jamaican woman and a White man from the Outer Hebrides, she began to search for traditional songs about Black people like her. By some estimates, circa 1800 there were 20,000 Black people living in London alone — but where were the songs about them?

Morrison did record one traditional English song, “The Brown Girl,” which she imagined might actually be a song about a woman with brown skin (as opposed to a mere poetic description). Then, in the tradition of generations of folk musicians, she decided to write her own songs in the idiom of traditional music, featuring non-White Britishers. In 2022, after having written a number of new songs, she released an album of those songs.

(A side note: if Morrison were working in the U.S. today, she would be accused of violating the recent presidential executive order titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” Don’t get me started on how that executive order tells lies about history.)

She is still mining this vein of material, and in her latest song is about the Black sailor William “Billy” Waters. I don’t know if Morrison saw the new book by Mary L. Shannon, Billy Waters is Dancing: Or, How a Black Sailor Found Fame in Regency Britain (Yale University Press, 2024) or if she did her own research (or both). In any case, Morrison’s song tells the same basic story that’s told in the book, which goes something like this:

William Waters was born in New York City (probably) around 1775. His family (probably) left New York when the British troops evacuated in 1783; little Billy would have been about eight years old. In 1811, he signed on as an able seaman in the British Royal Navy. Since he signed on as an able seaman, not an ordinary seaman, he (probably) had had previous experience as a sailor. Little else is known about his early life.

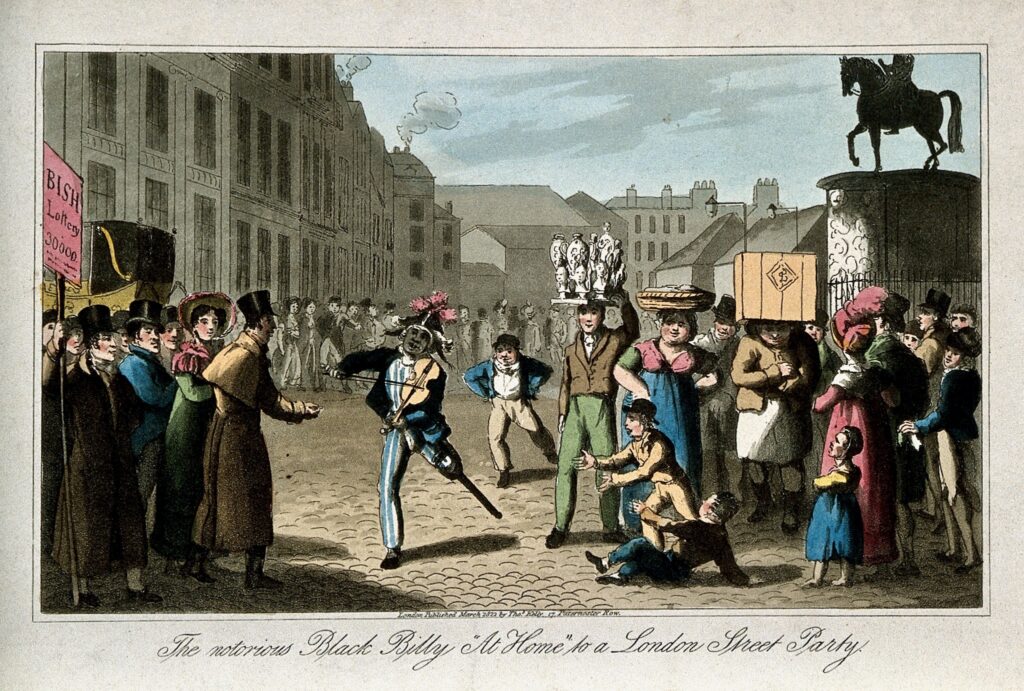

In 1812, the captain’s log reports that Waters fell from the from the main spar, broke both legs, and had to have one leg amputated. Waters was invalided out of the Navy with an inadequate pension, as was all too typical at the time. To earn enough money to live on, he turned to busking. He gained fame as a frequent performer outside London’s fashionable Adelphi Theatre. As many buskers did at the time, he adopted a distinctive dress: for Waters, this included his naval coat and a tricorn hat decorated with showy feathers. In his act, he not only sang and played fiddle, but he also danced with great dexterity; this last was considered remarkable due to his wooden leg.

Image courtesy: Wellcome Trust Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 .

Waters married and had two children. In spite of his fame, he and his family lived in St. Giles rookery, notorious as one of the worst slums in London. He died in 1823, aged approx. 60. At the time of his death, he was living in the St. Giles workhouse, an institution for indigent people. Presumably, by that time he was no longer able to earn his living busking. So much for his fame —sic transit gloria mundi.

As an able seaman, Waters would have had as good a life as could be expected for a working class man — and he could live in freedom, whereas slavery persisted in New York until well after his death. After he had his leg amputated, the Royal Navy didn’t treat him especially well. Yet in spite of his disability, he was able to earn enough money to allow him to provide for a family.

— And this is just one story telling how the American Revolution played out in the lives of ordinary people. We hear over and over again stories of how the Revolution affected prominent people like John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. I like to hear those old stories about those wealthy and prominent people who remained in America. But I also want to hear how the Revolution affected ordinary people, including the ones who left America. It’s hearing all those stories that makes history come alive for me.

(N.B.: Morrison’s song is so new, I couldn’t find lyrics to it anywhere online. I’ll post my own transcription of the lyrics after the jump.)

Jump Billy

Lyrics copyright 2024 Angeline Morrison. To support the songwriter, please purchase her recordings available on Bandcamp. My transcription is provided here for educational use — as we approach the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Concord and Lexington here in the U.S., go teach this song to kids!

CHORUS: Jump Billy, dance Billy, Billy spin around,

Fiddle for the people and they’ll pay their money down.

Jump Billy, dance Billy, Billy won’t you sing,

Fiddle for the people, for the crowds are gathering.

1. The King of the Beggars they call me; Billy Waters is my name;

Attend to my wondrous story: from rags to rags I came.

I once was an able seaman defending King and crown,

Until from the ship’s high rigging, poor Black Billy come a-tumbling down.

2. In this land of beggars, a far land, but I do fiddle and dance and sing;*

I leap and I spin for the gentry fine, all dressed up for their play-going.

I’m grand as a Lord in my naval coat, and my feathered tricorn hat,

The children say when I lost my leg, O, this fine leg of wood grew back.

3. I live in the rookery of St. Giles; Americay’s a long way home.

I’ve a fine little girl and a wife so dear: she’d melt a heart of stone.

The crowds outside the Adelphi, they throw pennies in my hat.

My wealth is my fiddle and my family and my fame; ’tis money I do lack.

4. A mass in the St. Giles workhouse in eighteen twenty-three —

Poor Black Billy did breathe his last in cruel poverty.

OUTRO: Polly won’t you marry me, Polly don’t you cry,

Polly go to bed with me, and get a little boy.

*Not sure I got Morrison’s lyrics correct here.

(In the outro, I don’t know who Polly is, or who is supposed to be speaking. Is it Billy Waters speaking? Is Polly his wife-to-be? Where does this fit into his story, and why does it come at the end of the song? Since I was indoctrinated by folksingers who said you gotta understand what you sing, I don’t sing the outro myself.)

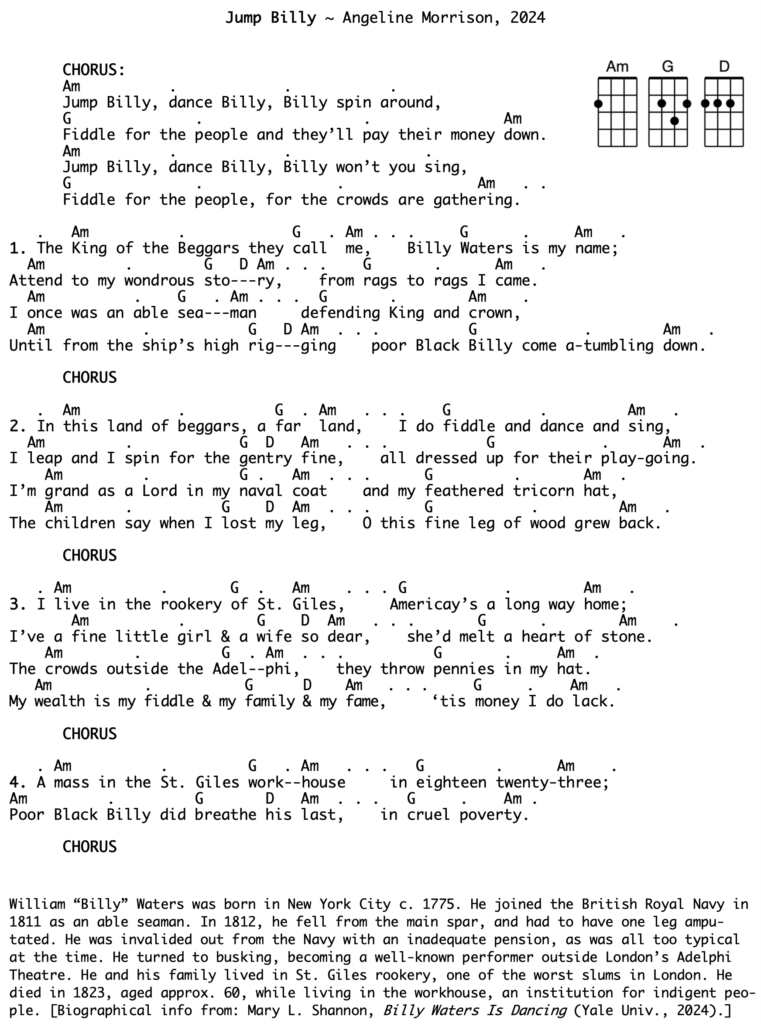

Uke chord sheet below, using San Jose Ukulele Club formatting: