For some reason, I got interested in the history of Southeast Asia a year or so ago. Mostly I was interested in learning more about a part of the world that was completely neglected in my schooling. Below are brief summaries of three of the books I’ve been reading.

A History of Myanmar

A History of Myanmar Since Ancient Times: Traditions and Transformations by Michael Aung-Thwin and Maitrii Aung-Thwin (Reaktion Books, 2012)

One goal of the Aung-Thwins, a father-and-son team of academics, is to write a history of Myanmar for Western readers that avoids Western bias. One of their arguments is that Westerners ignored independent Myanmar from its independence after the Second World War until 1988. This was at the end of the Cold War, when Westerners tended to interpret other countries as being either pro-democracy or pro-communist. The Burmese Way to Socialism began to unravel in 1988, so Westerners decided that everything in Myanmar should be understood in terms of a struggle for democracy. Thus Aung San Suu Kyi became the darling of the West, even though her political party performed poorly in elections. Aung San Suu Kyi’s father was Aung San, and the most prominent leader of Myanmar in the early days of independence. Aung San Suu Kyi added his name to her own to increase her name recognition. Interestingly, Aung San collaborated with the Japanese during the Second World War, although Westerners seem to have forgotten that Aung San Suu Kyi’s father worked with an enemy of the West.

In short, this is a good book for challenging any preconceptions you might have about Myanmar. Sadly, the writing isn’t very good — to give just one example, the authors love to use scare quotes, often for no apparent reason. Another problem with this book is that it was written in 2012, and it ends on a positive note; yet here we are in 2025, into the fifth year of a vicious civil war that shows no signs of ending. In spite of its weaknesses, this is just about the only one-volume history of Myanmar in English, so it’s worth reading.

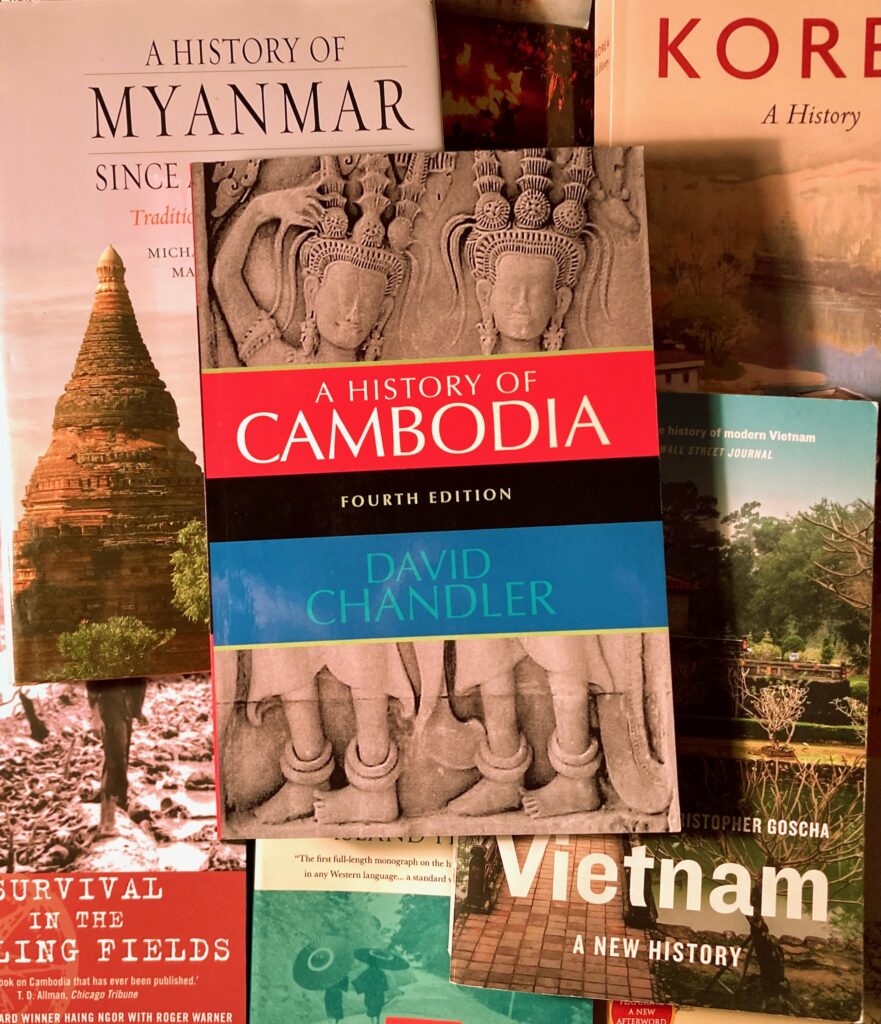

A History of Cambodia

A History of Cambodia, fourth edition, by David Chandler (Routledge, 2008)

An excellent one-volume introduction to Cambodian history. The author draws on a wide range of sources, including archeology, inscriptions, artworks, etc. He has to, since prior the colonial era, there are very few written sources, aside from accounts written by foreigners. Then when there are written sources, those sources mostly ignore the lives of the peasants.

Chandler challenges the old myth that Cambodian culture is somehow “timeless” — a myth that was all too often perpetrated by colonial powers on colonized peoples. Instead, Chandler traces the changing cultural influences, from the “Indianization” of two millennia ago, to that of European colonial powers.

After the Ankgor period and before European colonization, Cambodia existed as a small relatively powerless country caught between Thailand and Vietnam. During this period, Cambodia’s rulers did their best to balance these two powers against one another. They weren’t always successful; Vietnam, for example, wound up colonizing parts of Cambodia, and there wasn’t much Cambodia could do about it. Then the European powers showed up in Southeast Asia, and France took over, ending Cambodia’s existence as a separate country until after the Second World War. When the Second Indochina War (a.k.a. the Vietnam War) spilled over into Cambodia, once again there wasn’t much that Cambodia could do. The horrors of the Vietnam War blended right into the even greater horrors of the Killing Fields; Chandler’s account of the Khmer Rouge atrocities is brief but excellent, and for the first time, I felt like I had a good sense of what happened in those horrific years.

Chandler tries to end the book on a positive note:

“With a soaring birth rate, poor health, and a government that seems to be unprepared to be genuinely responsive to people’s needs, the prospects for the short and medium term appear to be very bleak. However, the resilience, talents, and desires of the Cambodian people, and their ability to defy predictions, suggest that a more optimistic assessment of their future might possibly be in order.”

Vietnam: A New History

Vietnam: A New History by Christopher Goscha (Basic Books, 2016)

Goscha’s book attempts to correct late twentieth century English-language histories of Vietnam, ones like Frances FitzGerald’s renowned Fire in the Lake. At the beginning of his book, Goscha writes:

“Whether one is for or against American intervention in Vietnam, there are serious problems in terms of how American-focused accounts of the wars like these represent the American past. By assuming that Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam of 1955 incarnated a timeless, traditional Vietnam with its roots deep in antiquity, FitzGerald gives us a very essentialized, unchanging Vietnam.”

As a corrective, Goscha traces how Vietnam changed over the past millennium or so. Early Vietnam was centered around the Red River, near the present Hanoi. Early on, Vietnamese culture was largely derivative of Chinese culture. From its origins in the north, the Vietnamese pushed south, colonizing the Cham kingdom in what is now southern Vietnam, and even pushing into Cambodia. Thus, the current S-shaped Vietnam does not represent the original boundaries of the Vietnamese polity. Thus it is not a timeless unchanging society; Vietnam has a long history of change and growth.

Goscha also offers a corrective to late-twentieth century histories of what we call the Vietnam War. Actually, says Goscha, that was the second of three Indochina Wars. In the First Indochina War, the Vietnamese and other peoples in French Indochina fought for freedom from France. In the Second Indochina War, Vietnam continued to fight for an independent existence, while also serving as the location of a proxy war between Western democracies and communist powers. From a historian’s point of view, because this second war spilled over into Laos and Cambodia, calling it the “Vietnam War” seems like a bit of a misnomer; calling it another Indochina War makes a lot more sense. Then there was the Third Indochina War. The immediate combatants were the Khmers Rouges in Cambodia and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, but this was also another proxy war, this time between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. Mikhail Gorbachev started working towards an end to this third Indochina war, but it was really the fall of the Soviet Union that put a final end to it.

This is another well-written book. However, it’s also pretty depressing. If you include the Japanese invasion of Indochina during the Second World War, Vietnam was at war almost continually for about half a century. And while we in the United States continue to mourn all the soldiers who died in Vietnam, the number of Vietnamese deaths was an order of magnitude greater. How a people can recover from such trauma is hard to understand.