In an earlier post, I published the first of a series of two sermons preached by Rev. Jacob Flint here in Cohasset in December, 1823. In these sermons, Flint proclaimed publicly that he supported the Unitarian side of the Unitarian / Trinitarian controversy then raging through eastern Massachusetts churches of the Standing Order. Not surprisingly, once their minister openly espoused Unitarianism, the Trinitarian sympathizers in the congregation left to form their own Trinitarian church.

I’m finally getting around to publishing the second sermon, the one that Flint preached in the afternoon. I can’t help wondering how the Trinitarian sympathizers responded after hearing the first sermon, the one in the morning. Did they gather together during the lunch break to talk? Did some of them refuse to return for the afternoon sermon? If they did return, were they angry as they sat there listening to their minister tell them that their cherished theological beliefs were irrational, non-Biblical, and even unchristian? And how did the Unitarian sympathizers in the congregation feel? — were they perhaps relieved that at last their minister came out and stated openly the beliefs that probably everyone in the small town of Cohasset knew he held?

It turns out to be a fairly well written sermon. Today’s Unitarian Christians might even find it to be of mild theological interest.

But I suspect most of the interest this sermon holds today is its historical interest. It’s a sermon that cause an open rupture between Unitarians and Trinitarians in one small town. It is in a sense a microcosm of the larger theological and institutional battle raging through organized religion in eastern Massachusetts. Flint was not arguing about abstract theological issues; he was arguing with people that he knew well, people he saw every day. His sermon might even cause us to reflect on the power of words and the power of thought, and how words and thought can lead to open conflict and (according to tradition) acrimony as well.

Original page breaks are noted in square brackets, like this: [p. 14]. Footnotes from the original have been numbered and placed as endnotes. A few editorial notes have been included, always enclosed in square brackets.

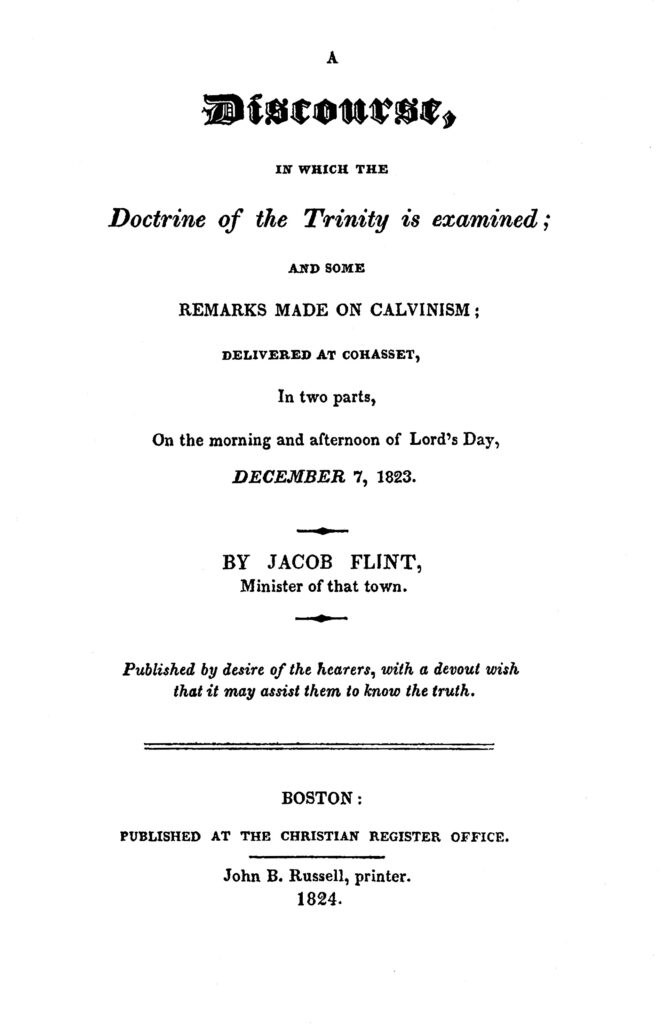

Discourse in which the Doctrine of the Trinity is examined…

by Jacob Flint (Christian Register: Boston, 1824).

[p. 11] PART II

[1] Thes[salonians] v. 21. — “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.”

The Scriptures, given by inspiration of God, contain, as I attempted to show you in the morning, a system of doctrines and morals admirable for their simplicity and truth, and a most necessary guide for men to faith, duty, and happiness. They are in the highest degree profitable for doctrine, reproof, correction, and instruction in righteousness. But I had to remark, that unhappily for the peace of society, and good will of christians towards each other, these sacred writings had not long been in the hands of fallible and and erring mortals, before they were made to teach, for doctrines, the inventions and commandments of men. These inventions, or spurious doctrines, became the source of almost endless dispute, animosity and persecution among christians. For these dreadful effects, however, there is no blame that can justly be attached to the gospel, because that every where inculcates forbearance, charity, and good will in all men.

Continue reading “The sermon that split a congregation, part two”