A follow up to an earlier brief post on the deity Doumu.

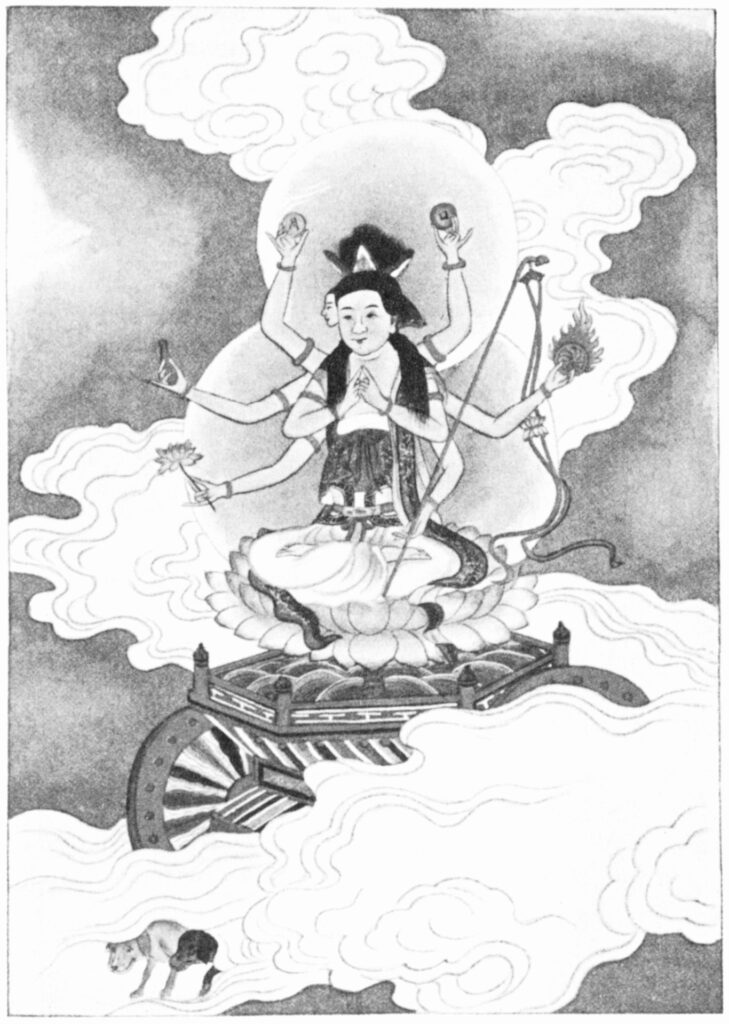

Doumu, a Daoist deity, is sometimes called “Dipper Mother” in English because she’s the goddess of the of the Big Dipper, Ursa Major. Her name is variously rendered Doumu, Tou Mu, Dou Mu Yuan Jun, etc. The illustration above shows a Qing dynasty sculpture of her in the collection of the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Doumu has nine pairs of arms. She also has three eyes. In the sculpture on the cover, the third eye is hard to see, but it’s there — between her other two eyes, in a vertical orientation in the middle of her forehead.

Back in 1912, E. T. C. Werner gave a summary of Doumu’s attributes and powers in his book Myths and Legends of China:

“Tou Mu, the Bushel Mother, or Goddess of the North Star, worshipped by both Buddhists and Taoists, is the Indian Maritchi, and was made a stellar divinity by the Taoists. She is said to have been the mother of the nine Jen Huang or Hu-man Sovereigns of fabulous antiquity, who succeeded the lines of Celestial and Terrestrial Sovereigns.

“She occupies in the Taoist religion the same relative posi-tion as Kuan Yin, who may be said to be the heart of Buddhism. Having attained to a profound knowledge of celestial mysteries, she shone with heavenly light, could cross the seas, and pass from the sun to the moon. She also had a kind heart for the sufferings of humanity. The King of Chou Yu, in the north, married her on hearing of her many virtues. They had nine sons. Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun came to earth to invite her, her husband, and nine sons to enjoy the delights of Heaven. He placed her in the palace Tou Shu, the Pivot of the Pole, because all the other stars revolve round it, and gave her the title of Queen of the Doctrine of Primitive Heaven. Her nine sons have their palaces in the neighbouring stars.

“Tou Mu wears the Buddhist crown, is seated on a lotus throne, has three eyes, eighteen arms, and holds various precious objects in her numerous hands, such as a bow, spear, sword, flag, dragon’s head, pagoda, five chariots, sun’s disk, moon’s disk, etc. She has control of the books of life and death, and all who wish to prolong their days worship at her shrine. Her devotees abstain from animal food on the third and twenty-seventh day of every month.

“Of her sons, two are the Northern and Southern Bushels; the latter, dressed in red, rules birth; the former, in white, rules death.”

Unfortunately, Werner doesn’t tell us his sources. I’d love to know the date of his sources, because all deities have a tendency to change over time. Furthermore, Chinese culture is not monolithic, and I’d love to know the regional origins of Werner’s information. Nor does Werner tell us much about how Doumu’s devotees venerated her — all he says is that they abstain from eating meat two days a month, but what were her festivals, and how did devotees show their devotion on a daily or weekly basis?

Werner also neglects to tell us anything about the temples dedicated to, or named after, Doumu. For that information, we have to turn to other sources. An English language guidebook from 1912 briefly mentions one of Doumu’s temples on Tai Shan mountain:

“After a quarter hour’s climb (6 hrs. 50 min. [from the town of T’ai Fu]), the Toumu-kung ‘Temple of the Goddess of the Great Bear’ on the E. of the road. This temple, within whose walls are to be found a singular mixture of Taoist and Buddhist divinities, was inhabited up to 1906 by Taoist nuns.”

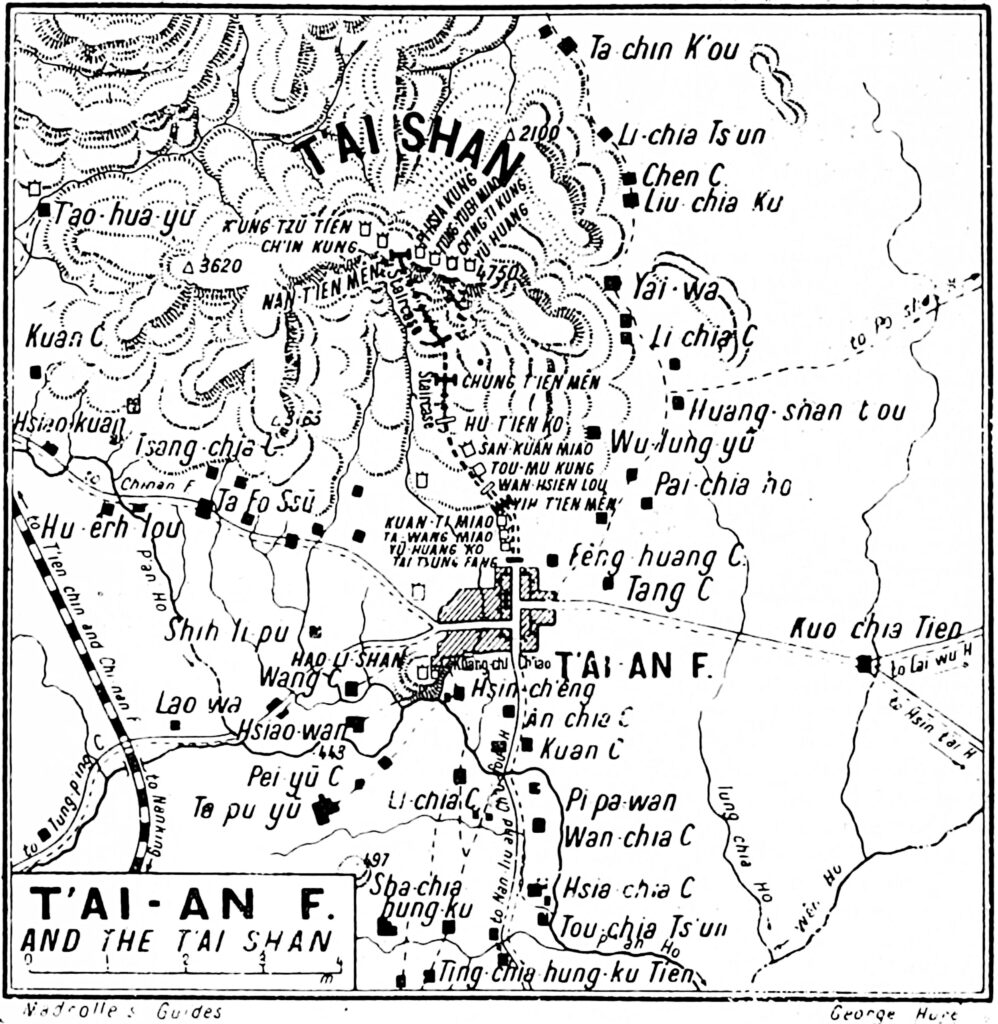

Tai Shan was one of the most sacred sites in China, and served as the home for other temples and sacred sites, as shown in the map below, from this 1912 guidebook. Doumu’s temple, labeled “Tou-Mu Kung,” appears almost in the exact center of the map.

It would be interesting to know if there were any relationships between the various temples. It would also be interesting to know something about the lives of the nuns who lived in the temple up to 1906. Doubtless there are Chinese language sources that could provide some or all of this information, but I was unable to find anything written in English.

Doumu’s temple on Tai Shan is still in existence. Wikimedia Commons has several photographs of the temple, taken by “Zhanzhugang” on 12 August 2015. Here’s Zhanzhuguang’s photograph of one of the entrances:

Other temples dedicated to Doumu exist today. For example, Doumu has a temple named for her at 779A Upper Serangoon Road, Singapore. A Singapore government website gives some more information about this temple:

“The Hokkien community refer to Tou Mu Kung as Kiu Ong Yah or Kau Ong Yah Temple (‘Temple of the Ninth Emperor’), which accurately reflects the main Taoist deity worshipped in the temple. While the temple is dedicated to Jiu Huang Ye, it is officially named in honour of another deity, Dou Mu Yuan Jun (‘Mother of the Big Dipper’), who is the mother of Jiu Huang Ye. Believed to be holding the Register of Life and Death, she is venerated by devotees in hope of prolonging one’s life and avoiding calamities. One version of the legend tells of Jiu Huang Ye as comprising nine stars: seven stars constituting the Big Dipper and two assistant stars that are invisible to the naked eye.

“Another legend describes Jiu Huang Ye as a single entity, often represented by an incense burner instead of a statue. This form of Jiu Huang Ye is adopted by Tou Mu Kung which enshrines the sacred incense burner on the upper floor of the two-storey pagoda behind the temple. Access to the pagoda is restricted to males.”

Although Jiu Huang Ye is still venerated by annual rites at the Singapore temple, there is no mention of any rites performed for Doumu.

But there is an annual festival in Singapore for her children, the Nine Emperor Gods. A Youtube video from 23 October 2023 shows scenes from this festival, including people lighting incense, leaving offerings, watching performances, etc. Electronic keyboards play side by side with traditional instruments for the Hokkien opera; flashing lights outline the ceremonial palanquins; devotees dressed all in white line engage in various activities. At one point someone drives a bright orange Lamborghini sports car into the festival. While this festival doesn’t directly involve Doumu, it takes place in her temple. It looks like a fun mixture of contemporary pop culture and folk religion.

Doumu entered the Daoist pantheon in the Ming and Qing dynasties, as an adaptation of the the Hindu goddess Marici (Despeux, 2000). Having similarities to Guanyin, she sometimes became associated with that deity. She then traveled beyond China to Southeast Asia, where she became associated with the Nine Emperor Gods.

According to Hock-Tong Cheu (2021), for ethnic Chinese people living in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia, veneration of the Nine Emperor Gods takes the form of veneration of Doumu. In Southeast Asia, she may be represented as either a Daoist or a Buddhist deity. Contemporary sculptures in these countries most often depict Doumu with nine pairs of hands. There are nine pairs to represent the Nine Emperor Gods. In sculptures, these eighteen hands hold precious objects “such as the sun’s disk, the moon’s disk, bow, arrow, spear, sword, flag, rosary, book, ruler, scissors, dragon’s head, gourd, fan, pagoda, chariots, precious gem” and other objects. Each of these objects provides insight into Doumu’s abilities:

“Informants reveal that each of these precious objects signifies Doumu’s power. The sun and moon disks, for example, portray her power in controlling the universe, through the manifestation of day and night, brightness and darkness, heat and cold, health and disease, life and death, etc.; the bow and arrow demonstrate Doumu’s power in protecting humankind against war and pestilence, and in maintaining peace and harmony; the flag is used as an emblem to signify her power in preserving human integrity and territorial sovereignty; the rosary acts as a medium through which Doumu inculcates devotion, piety, and asceticism as channels through which salvation [sic] may be attained; and so forth.”

But more than anything else, contemporary devotees of Doumu understand her as the deity of “Lovingkindness and Mercy.” Devotees perform rituals during the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, which is held each year for the first nine days and nights of the ninth lunar month, so that these offspring of Doumu will give them blessings of “fu lu shou,” or fortune, prosperity, and longevity.

Doumu hasn’t made much of an impact on Western society; a few practitioners of Westernized Daoism might know who she is, but New Age practitioners don’t seem to pay much attention to her, and she hasn’t made the ultimate leap forward in status by being included in a video game. But she is still widely venerated in east Asia.

Sources

Hock-Tong Cheu, entry on Doumu in Chinese Beliefs and Practices in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Partridge Publishing, 2021).

Catherine Despeux, “Women in Daoism,” in Daoism Handbook, ed. Livia Kohn (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2000), pp. 393 ff.

David B. Gray and Ryan Richard Overbey, Tantric Traditions in Transmission and Translation (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Claudius Madrolle, Northern China: The Valley of the Blue River, A Handbook for Travellers in Northern China and Korea, in the Madrolle’s Guide Books series (London: Hachette & Co., 1912), p. 163.

A Simple Video Youtube channel, “Tou Mu Kung Temple Nine Emperor Gods Festival 2023,” video from 23 October 2023, accessed 30 October 2023, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=tZ7U67il2qY

Singapore National Heritage Board, “Tou Mu Kung,” webpage accessed 30 October 2023, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/national-monuments/tou-mu-kung

E. T. C. Werner, entry on Doumu in Myths and Legends of China (London: George G. Harrap & Co., 1922), pp. 144-145.