Summary session plan below. Also, at the end of this post, a bunch of links and info requested by participants.

My iNaturalist observations for today and yesterday.

It was the last day of Ecological Spirituality class. Some participants had to leave early, some participants had to finish packing up, so there were only five of us. That meant we could do one of the most fun activities of all — whittling!

Whittling

How does whittling relate to ecojustice, and ecological spirituality? When we teach whittling to kids, it does the following:

- whittling empowers kids, teaching them how to use a potentially dangerous tool

- whittling connects kids with physical hands-on embodied doing (as opposed to seeing the world through a screen or through VR)

- whittling can be meditative

- learning how to use a pocket knife is a good skill if you’re going to spend much time outdoors

- whittling in a group teaches kids about being in community — because you have to learn how to whittle without hurting anyone around you (learning the physical limits of your body and the bodies of others, learning that what you do can unintentionally hurt others, etc.)

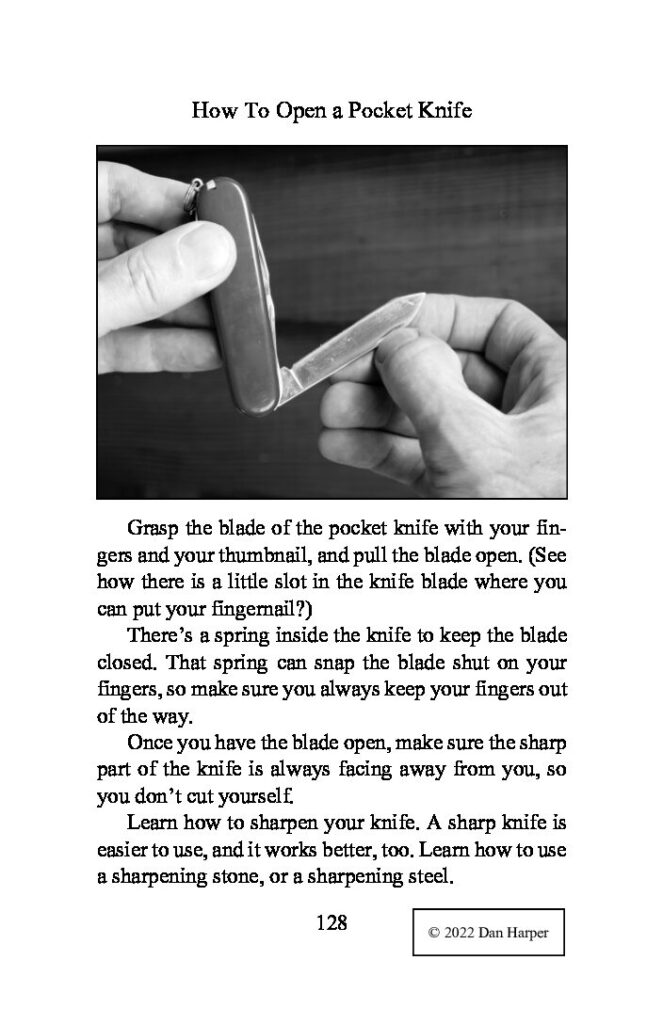

Even though our group was all adults, I went over basic kid-level instructions on how to to use a pocket knife. Here’s a version of those instructions, taken from the Ecojustice Outdoors Book:

What you do while whittling

One of the best parts of whittling is the conversations you have while whittling. The five of us had a wide-ranging conversation, mostly focused on education and educating for ecojustice.

Some links and information

1. Here are a couple of the resources I mentioned during our conversation:

“Reimagining Sunday School” — my short essay on four big educational goals to help structure all religious education

“Ecojustice” — a curriculum I co-developed and then wrote, aimed at middle schoolers

2. I mentioned nine “soul pathways.” This typology comes from a book by Gary Thomas, Sacred Pathways. I learned about the nine “soul pathways” from Heesung Hwang of Chicago Theological Seminary, in her presentation titled “Spiritual Formation for the Burnout Generation: With an Asian Spiritual Perspective” at the recent Religious Education Association conference. The nine types are:

- naturalists

- sensates

- traditionalists

- ascetics

- activists

- caregivers

- enthusiasts

- intellectuals

Here is Hwang’s summary of the nine “soul pathways”:

“[The first] of the nine spiritual paths is that of the naturalists. These people find God more deeply in nature than in reading religious books in a building. They experience God in nature more deeply than in reading theology books inside a building. They are similar to contemplatives, but they are more moved by creation. The second path is for sensates. Sensate Christians enjoy worshiping with all their senses. Thomas describes, ‘When these Christians worship, they want to be filled with sights, sounds, and smells that overwhelm them. Incense, intricate architecture, classical music, and formal language send their hearts soaring.’ Third, traditionalists connect to God through rituals, symbols, sacraments, and sacrifices. For them, other less structural ways seem outside the boundaries. The fourth path is that of the ascetics. They feel deeply connected to God when they experience solitude, simplicity, and prayer. Ascetics are often constrained by complex programming and active projects. They feel deeply connected to God when in a simple and quiet environment.

“Fifth, activists serve the God of Justice and often focus on justice or oppression of marginalized groups. They see action and confrontation as means of worship. The sixth pathway is the caregiver’s path. Caregivers like to provide physical and emotional support to others. It is through this service that they experience and practice God’s love. Caregivers often view other pathways as selfish. Seventh, there is the path of the enthusiasts. In the same way that sensates love beauty and intellectuals are inspired by understanding, enthusiasts are enthralled by joyous celebrations…. In the eighth path, there are contemplatives. They adore and revere God and often call God their lover. They don’t like public attention or seek to be in the spotlight. Those who follow the ninth spiritual path are intellectuals. They wrestle with ideas and concepts in order to get to know God better. In their view, spiritual experiences such as faith, doubt, and conversion are concepts to be understood as much as experienced.”

Some of my thoughts on applying this typology to Unitarian Universalism: Many local Unitarian Universalist congregations are still dominated by intellectuals, while activists have mostly taken over at the denominational level (plus, many ministers are activists, sometimes putting them at odds with the intellectuals in their congregation). In the congregations I’ve been part of, the caregivers make up the actual backbone of the congregation (pastoral care teams, people who give rides, Sunday school teachers, etc.) though their work is (at least in my experience) undervalued. Contemplatives, naturalists, and ascetics are tolerated in Unitarian Universalism, but tend to have relatively low status — unless they also engage in activism. Traditionalists, sensates, and enthusiasts have very low status in most of Unitarian Universalism, to the point where they may be driven out of local congregations.