Fairly complete lesson plans for today’s activities are below.

The Food Chain Game

(Heavily adapted from a game produced by “Project Wild”)

Basic ecological concept: ENERGY FLOW

Other ecological concept: How toxins can move through food chains.

Key concept statement: “Energy from the sun flows through all living things.”

Enrichment activity: Tell the story of Rachel Carson, and how she publicized the way DDT moved through the food chain. (You can find a brief story about Rachel Carson on this web page if you scroll down.)

Equipment:

30 “Plants” per player — “Plants” are made from crumpled pipe cleaners

10 Plants of a bright Yellow color (plus extras to use as needed)

20 Plants of a dark Blue color (plus extras to use as needed)

1 small paper bag per Grasshopper

1 medium paper bag per Vagrant Shrew

1 large paper bag per Barn Owl

Introduction:

Say something like this:

“This is the Food Chain Game!

“A food chain starts with energy from the sun, which is converted into food by plants, and then plants eat the animals. The food chain ends up with an apex predator.

“In our food chain, there are four organisms.

“First there are Plants (hold up a felt square). Plants convert the Sun’s energy into food. In a food chain, we call them ‘producers’ because they produce food.

“Then there are Grasshoppers. Grasshoppers are called ‘herbivores’ because they eat Plants. In a food chain, we call them ‘primary consumers’ — they are first link in the food chain.

“Next up in this food chain, we have Vagrant Shrews. Vagrant Shrews are called ‘insectivores’ because they eat insects, or we can call them ‘carnivores’ because they eat other animals. In a food chain, we call them ‘consumers’.

“At the top of this food chain are Barn Owls. Barn Owls are carnivores. In a food chain, we can call them consumers, or since they are at the top of the food chain we can call them ‘apex predators.’

“So that’s how this food chain works—

“Plants—producers that convert energy from the sun into food

“Grasshoppers—primary consumers—get energy from eating plants

“Vagrant Shrews—get energy from eating other animals

“Barn Owls—get energy from eating other animals.

“Energy comes from the Sun and moves up along the food chain to the apex predator.

“Now we’re going to play the Food Chain Game. We’ll start with the easy version, and then do the more complicated version.”

Simple version of the Food Chain Game:

Find a large play area. Show everyone the boundaries, and tell them that this is the Habitat.

Now divide up the players into Grasshoppers, Vagrant Shrews, and Barn Owls.

For each Barn Owl, there are at least 3 Vagrant Shrews.

For each Vagrant Shrew, there are at least 3 Grasshoppers.

This could work out something like this:

For about a dozen players, you might have 1 Barn Owl, 3 Vagrant Shrews, 9 Grasshoppers.

For about 25 players, you might have 2 Barn Owls, 8 Vagrant Shrews, and 15 Grasshoppers.

Each Grasshopper gets a small paper bag, which represents their body/stomach.

Each Vagrant Shrew gets a medium sized paper bag, which represents their body/stomach.

Each Barn Owl gets a large paper bag, which represents their body/stomach.

Tell the rules of the game (see below).

You might want to make sure the Grasshoppers cannot see you scatter the Plants in the Habitat.

Rules of the game:

First of all, think of this as a Role Playing Game. (If you know Dungeons and Dragons, you can say it’s a little like D&D, where you’re the dungeon master who controls everything.) So the point is not so much to win or lose, as it is to explore this universe that you’re in. Now for the rules:

First the Grasshoppers have about 30 seconds to hunt for Plants (more time for big Habitats) before Vagrant Shrews and Barn Owls start hunting. While Grasshoppers are finding food, the Vagrant Shrews and the Barn Owls watch from the edge of the Habitat. Remind Vagrant Shrews and Barn Owls that they are predators, which means that they will want to watch quietly so as not to scare away their prey — while Grasshoppers are finding Plants, Vagrant Shrews and Barn Owls can quietly move anywhere around the edge of the Habitat, but they must not step into the Habitat.

Next, Vagrant Shrews begin hunting. They have about 15 seconds to hunt for Grasshoppers (depending on size of the Habitat; the leader might make sure that each Vagrant Shrew gets a chance to tag at least one Grasshopper) before the Barn Owls start hunting. Vagrant Shrews catch their prey by tagging a Grasshopper. When a Grasshopper gets tagged, they have to give their paper bag with Plants to the Vagrant Shrew who tagged them, then they go to the edge of the Habitat to become compost. The Vagrant Shrew then puts the Grasshopper’s paper bag into their paper bag. While the Vagrant Shrews are hunting, the Grasshoppers that are still alive can continue to hunt for Plants. (You can have extra Plants to throw out into the Habitat if needed, though after you’ve played this a couple of times you’ll figure out how many plants to have right up front.)

Finally the Barn Owls begin hunting. They have about 30 seconds to hunt for Vagrant Shrews. Barn Owls catch their prey by tagging a Vagrant Shrew. When a Vagrant Shrew gets tagged, they have to give their paper bag to the Barn Owl who tagged them, then they go to the edge of the Habitat to become compost. While the Barn Owls are hunting, any Vagrant Shrews and Grasshoppers that are still alive can continue to find food.

At the end of the round:

Each time an organism eats, it gets energy from what it eats. So once you eat a Plant, it turns into Energy. All these things in those paper bags? They aren’t Plants any more, now they are Energy. But it also has to use up Energy to find food, and to avoid being caught by something else.

So let’s pretend each organism uses up half its Energy, and only passes along half its Energy to whatever organism eats it. [If anyone asks, say there’s no difference between the different colored plants this round.]

Grasshoppers, count your Energy. Half of that is your total energy.

Vagrant Shrews, count your Energy. A quarter of that is your total energy.

Barn Owls, count your Energy. An eighth of that is your total energy.

Let’s pretend (and we’re really making these numbers up) — let’s pretend Grasshoppers need need 4 total Energy to reproduce, Vagrant Shrews need 8 total energy to reproduce, and Barn Owls need 16 total energy to rerpoduce. If you have enough total energy, then you get to remain the same organism next round. (Assign everyone else to be a new organism next round, using the same rough proportions.)

?

There are many variations of these rules.

Variation one:

Different color felt squares — Plants — turn out to have different energy values. This would be true for some of the food sources that actual grasshoppers eat.

Variation two:

The basic Rules are the same, but scoring is going to be different this time!

At the end of a round, have the Grasshoppers stand together, the Vagrant Shrews stand together, and the Barn Owl(s) stand together.

For all organisms that were left alive, have them pull the Plants out of their paper bag. Tell them that Plants colored Red (or whatever color you choose) have pesticide. This pesticide takes many years to break down, and so it accumulates in the food chain. [This models mercury-based chemicals, etc.]

So you need the same total energy to reproduce as in the basic rules. BUT if you’re a Vagrant Shrew and you have 4 or more Red felt squares, you die. If you’re a Barn Owl, and have eight or more Red felt squares, you are unable to reprduce; if you have 16 or more Red felt squares, you die.

Variation three:

You can come up with complicated scoring schemes to model different aspects of how a food chain works. You can also come up with scoring schemes that are more competitive, for example:

Competitive scoring:

Organisms that were eaten:

— You get +1 point for contributing to the food chain

Grasshoppers who don’t get eaten:

— Living Grasshoppers get +1 point for every 3 Plants

— You can also have a rule where different colored Plants provide different amounts of energy

Vagrant Shrews and Barn Owls:

— For each Plant colored Red, -1 point (that’s minus one)

— For each Plant NOT colored Red, +1 point

— Take your total and subtract one half (for the energy you expended in hunting)

— A score of zero or less means you die

Follow up conversation:

Review first:

— What was it like to play the game? What was it like to be each organism?

— In the first round, what did you think when you learned how much Energy you needed to reproduce (to have children)? Was that a fair number, or do you think it should have been more or less? Was it harder to be a Grasshopper, a Vagrant Shrew, or a Barn Owl?

— In the second round, what did you feel like when you found out about the pesticide?

OK, harder questions:

— How do you think animals would feel if they knew that all of a sudden their food had pesticide in it? [Point out that the Grasshoppers did not know ahead of time which color of Plant would kill them—that would be true in the real world, where insects do not know when a pesticide has been used (that’s how pesticides kill insects!). And of course higher predators can not know if their prey has accumulated any pesticides in their bodies.]

— Is there any way for Grasshoppers, Vagrant Shrews, and Barn Owls to play this game so they are less likely to get killed by pesticides? [Remember, you have to get energy from the sun; and once certain pesticides are in the food chain, they stay there!]

Notes to The Food Chain Game

(1) This food chain is very generalized, and should not be taken as an accurate model.

(2) You can spend a lot of time trying to make this a more accurate and relevant model. So…

The food chain in the original version of this game included Plants, Grasshoppers, Vagrant Shrews, and Hawks. These species does not really make up a food chain in the San Francisco bioregion where I first played this game, so I changed the species. If we try to imagine a similar food chain for our bioregion (Santa Cruz Mts. and surrounding lowlands), the following species might work:

— there are various grasshoppers in our area, including e.g. species of coneheads/katydids, which I just gave the generic name of “grasshoppers”

— of the 3 main species of Shrew in our area, the Vagrant Shrew is probably most relevant, as it prefers “open grassy situations” whereas other Shrews in our region are more likely to be forest dwellers (California Department of Fish and Game, 1999. California’s Wildlife, Sacramento, CA. Written by: J. Harris, reviewed by: H. Shellhammer, edited by: S. Granholm, R. Duke. http://www.sibr.com/mammals/M003.html)

— for the Vagrant Vagrant Shrew, Barn Owls, not Hawks, are reported to be the most important predator (along with Bobcats). Barn Owls do not have the same problem with thinning shells that some Hawks have (a fact in the original games), but bioaccumulation of toxins is a problem for owls (https://www.owlpages.com/owls/articles.php?a=59#toxicology).

— Here’s why I dropped Hawks from the game — Of the hawks in our region, smaller hawks specialize in other food (e.g., Cooper’s Hawk specializes in birds); larger hawks (e.g., Redtails) are more interested in larger mammals than Vagrant Shrews; Northern Harriers take a great many small mammals, but they tend to hunt in habitats (marshlands) that do not have a large number of Vagrant Shrews in our area. Barn Owls, on the other hand, are a major predator of Vagrant Shrews, so they are the obvious raptor from our bioregion to substitute in this food chain.

(3) When playing with children, I like to show images of the organisms in the model (easily available from Wikipedia and other online sources). The pictures help the children visualize what the organisms look like, and helps them become more involved in the game as a role playing game. If I were playing this game frequently, I’d think about creating simple costumes, or maybe putting images of the organisms on the paper bags.

(4) To relate this activity more directly to Rachel Carson, you could look into which food chains she researched. It would be fun to come up with a food chains with Peregrine Falcons or Ospreys as the top predator.

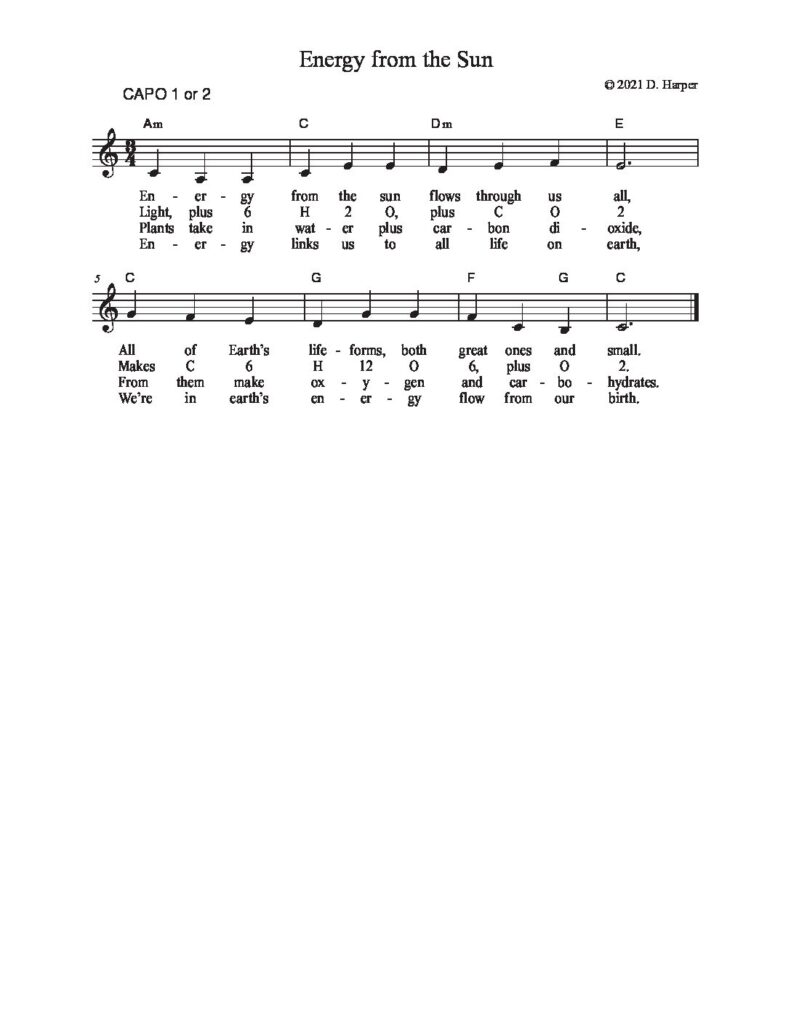

Energy from the Sun song

After playing the Food Chain Game, we sang the following song:

Alone walk

[The instructions below are for doing this activity with children in gr. 2-8. I did a slightly different version of this activity in today’s workshop.]

Educational goal: sensory awareness

Find a section of trail that’s unlikely to be disturbed by others walking along it. And make sure there’s no poison oak or poison ivy.

Have everyone sit in a circle.

“We’re going to do a silent walk. Lorraine will be at the front of the line, and I will be at the back. We’re going to walk slooooowly.

“As we walk, one by one I will tap the last person in line on the shoulder. When you get tapped, you stop right there. That place is now your place to spend time alone in.

“Now you’re not going to be completely alone. I’ll space you out so that you’ll be able to see the person in front of you and the person behind you.

“But think of this as your time alone in the woods. The only rules are you can’t talk, and you can’t disturb the people in front of you or behind you.

“What can you do? Here’s what other kids have done on alone walks: Sit and do nothing. Build a fairy house. Break sticks. Look for seeds. Write in your field notebook. Lie on your back and look up into the trees.

“Whenever I’m alone in the woods, the main thing I try to do is to stop listening to that little voice in the back of my head. Most of us have that little voice; it chatters on and on, commenting about what I’m doing, reminding me of the things I should be doing, blah blah blah. If you can ignore that voice in the back of your head long enough, it will gradually fade away, and you will be able to finally really hear the world around you.”

I usually ask the campers how long they want to be alone. 5 minutes? Ten minutes? Older kids may ask for 20 or 30 minutes. Then line everyone up and start walking just as described above — notice when you drop off the first camper, and start your timing from then.

I usually find a trail that goes in a circle, so we adults can keep an eye (or really an ear) on things.

When the time is up, start back down the trail, and pick up the campers one by one. If you need to, whisper, “No talking yet.”

Do a closing circle.

“What did you see?”

“What did you hear?”

“What did you smell and touch?”

Then when everyone has spoken who wants to:

“Were you able to ignore the voice in the back of your head?”

“What did it feel like to be alone in the woods?”