Part Six of a history I’m writing, telling the story of Unitarians in Palo Alto from the founding of the town in 1891 up to the dissolution of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1934. If you want the footnotes, you’ll have to wait until the print version of this history comes out in the spring of 2022.

Part One — Part Two — Part Three — Part Four — Part Five

Decline and dissolution, 1926-1934

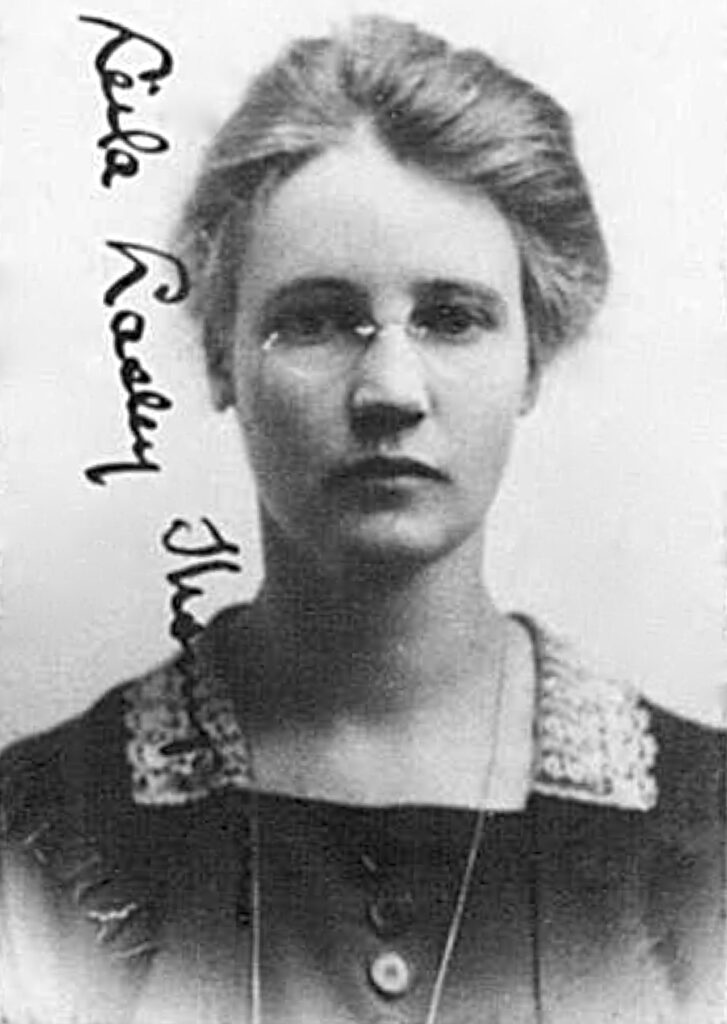

In late 1925, Elmo Robinson could look back on “four happy years, profitable to me, and I hope to the church.” But he had grown restive. He received a grant so that he could study for a semester at Harvard University in the first half of 1926. He found, or the church found, Leila Lasley Thompson to fill in for him while he was away. Thompson had married a soldier in 1918 who then was killed in action a few months later, leaving her a war widow. She then studied for the ministry at Manchester College, Oxford, England, a Unitarian theological school; was fellowshipped as a Unitarian minister by the American Unitarian Association; and pursued post-graduate study in 1925 at the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry.

Robinson departed at the end of 1925, leaving Leila Thompson in charge of the congregation. The congregation ordained her on Sunday, February 7, 1926. A month or so later, Robinson decided that he wasn’t going to return to the church. He apparently decided to pursue an academic career, although a note from him dated April 5, 1926, has a cryptic reference about protecting himself from “the charge of using this leave of absence as an opportunity of running away from an unpleasant situation without giving everyone a chance to be heard.” The “unpleasant situation” may well have been the long-standing conflict between the pacifist faction and the pro-war faction. Not even Robinson, with his skill and experience, had been able to heal that conflict.

After going east, Robinson never returned to Palo Alto — which sounds a little too much like Bradley Gilman’s departure from the church. In September, 1926, the church called Leila Thompson as the sole minister of the church. She was reportedly the first regularly ordained woman to serve a minister of a Palo Alto church.

Sadly, Leila Thompson received little support from the lay leaders. Sunday morning attendance dropped even more, from 34 in 1925, down to 27 in 1926, and then to 22 in 1927. Sunday school plummeted from 62 in 1925 down to 25 by 1927. The Young People’s Group continued to be active; Gertrude Rendtorff was still a Stanford student, and perhaps her continued participation kept that group going.

Alfred S. Niles, a lifelong Unitarian, moved to Palo Alto with his wife Florence, also a Unitarian, in the fall of 1927. When they arrived in town, Alfred and Florence sought out the Unitarian church. He found a church that was “still functioning, but rather feebly.” He was told that the church had once been active, “but the minister at the time of World War I had been a pacifist and conscientious objector [i.e., William Short, Jr.], and this had caused a split in the church from which it never recovered.”

Attendance got so low that the congregation tried moving the services to the evening, but that didn’t help matters. At the end of December, 1927, Leila Thompson resigned. It appears from the extant records that everyone became aware that there really wasn’t enough money to pay her salary any more, not even with the assistance the church still received from the American Unitarian Association. The church got Clarence Vickland, a student at the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry, to come preach to them in 1927-1928. Sunday morning attendance continued to drop, down to an average of 21, and by December, 1928, the Sunday school had closed “as there was not sufficient interest manifested to justify continuing the work.”

Finally, in 1929, the church stopped holding services altogether. Clarence Vickland wrote to the Women’s Alliance asking if they would like to host a visiting Unitarian minister on March 3, but they replied that “it would be impossible to get the congregation together.” 1929 was also the year that Karl and Emma Rendtorff retired to Carmel. With the Rendtorffs about to leave town, there was no real hope for the church. In May, 1930, Rufus Hatch Kimball reported to the Women’s Alliance that the Board of Trustees had turned the church building over to the American Unitarian Association. The church had finally dissolved.

The Women’s Alliance was declining, too. They continued to work on charitable projects — at their June, 1932, meeting, they worked on sewing for the Needlework Guild — but their numbers were shrinking. By May, 1930, the membership list had only nineteen names, and after Anna Probst Zschokke’s name appeared the notation, “Died May 30, 1929.” Like the church, the Alliance was slowly winding down and dying away.

The building sat vacant until early 1931. Then in February, 1931, Mary Engle reported to the Alliance that the American Unitarian Association had begun fixing up the building, and it was “now all in good repair and new locks have been put on the doors so that no invading hands could open them and…have access to Church of Alliance property.” By Easter Sunday, services were once again being held in the church, and Merrill Bates, the theological student who had been given charge of the church, had started up the church school once again.

The Alliance tried to help with the revived Sunday school, but grew discouraged with the tiny attendance, leaving Merrill Bates to manage on his own. Merrill Bates, Berkeley Blake, regional field secretary for the American Unitarian Association, and William S. Morgan, president of the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry, each preached to the church once a month, with Bates arranging supply preachers for the other Sundays.

Bates continued in the Palo Alto church until he graduated in spring of 1934. It’s hard to know how many of the old-time members still participated in the church. On March 27, 1932, Henry David Gray, who had become a member of the church in 1905, preached the Easter sermon. But most of the old members had either died, or moved away, or given up on the church. The Alliance held its last meeting on October 11, 1932, without even coming to a conclusion as to whether they should formally dissolve or not.

In April, 1934 — a month or so before Merrill Bates graduated from the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry — the American Unitarian Association put a “For Sale” sign up in front of the building. The building soon sold, for less than its mortgaged value. The American Unitarian Association retained possession of the organ, however, and gave it to the Unitarian church in Stockton, Calif. on permanent loan (Clarence Vickland was then the minister in Stockton). As Alfred Niles put it, there would be “no more organized Unitarianism in Palo Alto for several years.”

Interregnum, 1934-1947

Indeed, there was no organized Unitarianism in Palo Alto for almost exactly thirteen years. In 1936, the liberal Quaker Elton Trueblood became the chaplain at Stanford University, and some Unitarians — like Alfred and Frances Niles — found Stanford’s Memorial Church a congenial place to go on Sunday mornings. Other Unitarians found other religious homes. Josephine Duveneck became active with the American Friends (Quaker) Service Committee, and eventually became a Quaker herself. Alice Locke Park also became a Quaker. Several Palo Alto Unitarians gave up on organized religion altogether.

Even for the Unitarians who went to hear Elton Trueblood preach each week at Stanford, there was no Unitarian Sunday school for those with children, and there was no Unitarian minister to officiate at rites of passage such as weddings and funerals. Perhaps more importantly for many, there was no Unitarian community of which to be a part. Then when Elton Trueblood left Stanford in 1945, there wasn’t even any liberal preaching in town.

In May, 1944, the American Unitarian Association organized the Church of the Larger Fellowship to serve Unitarians who didn’t have a nearby Unitarian church that they could belong to. This was a sort of mailorder church which sent monthly newsletters with sermons and other material of interest to Unitarians; it was, in a sense, an expansion of the old Post Office Mission. The Church of the Larger Fellowship grew quickly, and within three years, a dozen or so Palo Alto Unitarians had already joined.

A New Congregation, 1947

In November, 1946, Alfred Niles saw a notice in the Christian Register, then the name of the denominational periodical, that the American Unitarian Association had appointed Rev. Delos O’Brian to be the the Regional Director for the West Coast, with an office in San Francisco. In February, 1947, Alfred Niles made an appointment to visit Delos O’Brian, who showed him two lists of names from the Church of the Larger Fellowship, one with a dozen names from the Palo Alto area, and another with a dozen names from San Mateo. Delos O’Brian was still undecided whether to organize a new Unitarian church in Palo Alto or San Mateo, and Alfred Niles later claimed that it was his visit that helped tilt the balance to Palo Alto. And on April 6, 1947, Delos O’Brian held an initial meeting to organize a new Unitarian group in Palo Alto. The Palo Alto Unitarian Society, as it was first known, grew quickly. Organized Unitarianism had finally returned to Palo Alto.

But even though many of the members of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto still lived in the area, most of them did not join the new congregation. Ruth and Everett Calderwood, who were only in their fifties, first claimed they were too elderly to take part, though later they did make financial contributions to the church. Katherine Carruth, who was then seventy-one, said she was sorry but she was too old to participate.

Edna True, on the other hand, who at seventy-two was older than the Calderwoods or Katherine Carruth, attended the very first meeting of the society, and became a member of the congregation. Clearly, while some Palo Alto Unitarians retained their enthusiasm for being part of a Unitarian church, others had lost all such enthusiasm. When Dan Lion arrived in Palo Alto as the first full-time minister of the new church, he made contact with some of the former Palo Alto Unitarians. He made an audio recording of his memories of calling on some of those former Palo Alto Unitarians, and while that recording has been lost, nevertheless, we can make a pretty good guess why those former Palo Alto Unitarians stayed away — the bitter conflicts that split the church, the incessant lack of money, the sense that they had been betrayed by some of their ministers and by the denomination, all contributed to drive these people away from any Unitarian congregation.

Other former Palo Alto Unitarians were happy to join the new congregation. Alfred and Frances Niles were central figures in the new congregation. Edna True was a member of the congregation up until she died, when she left a large bequest to the church. Rufus Kimball was integral in helping the new congregation claim its tax-exempt status. Ruth Steinmetz, a graduate of the old church’s Sunday school, joined the new church and remained active in it the rest of her life. Cornelis Bol, who had moved to Holland before the First World WAr, returned to Palo Alto in time to join the new congregation. Walter Palmer, who lived in Oakland by then, heard about the new church, and contacted them saying that he had been one of the charter members of the old church, and would like to be on the mailing list, though he wouldn’t be able to participate. Gertrude Rendtorff, living in Monterey, also heard about the new church in Palo Alto and asked to be on the mailing list.

Then too, as time went on, descendants of some of those former Palo Alto Unitarian families resumed a connection to the church. Guido Townley Marx, grandson of Palo Alto Unitarians Guido H. and Gertrude Marx, was married in the new church. Candace Longanecker, granddaughter of Errol and Laura Longanecker, was another grandchild who was married in the new church. And over the years, Dan Lion officiated at the memorial services of a handful of those former Palo Alto Unitarians.

The new congregation, renamed the Palo Alto Unitarian Church in 1951, was wildly successful. By 1965, they had three worship services each Sunday, and the Sunday school had some six hundred children enrolled. In less than twenty years, the Palo Alto Unitarian Church became one of the largest Unitarian congregations on the West Coast. So why did the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto die, and the new Palo Alto Unitarian Church succeed?

Partly, it was a matter of demographics and the economy. Before the Second World War, Palo Alto was a small town, probably too small to support a viable Unitarian church. After the war, both Palo Alto and the surrounding area gained population rapidly while at the same time the economy was booming. This meant the new congregation could grow quickly so it didn’t need to be subsidized by the denomination, and furthermore the new congregation could attract, and pay for, excellent professional leadership. But then when the new congregation faced financial stress in the late 1960s and early 1970s, due both to demographic decline and a declining economy, conflict erupted and membership and participation plummeted. Demographics and the economy are major influences on congregational growth and decline.

It was also partly because the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto was unable to integrate new leadership. It’s no coincidence that the congregation died within a year after Karl and Emma Rendtorff retired to Carmel. By the 1920s, the Women’s Alliance consisted solely of elderly and middle-aged women; the older women had not made room for young women to be part of the Alliance. As they aged, the small core of leaders that ran the old church was reluctant to share power with younger people.

Then too, the conflicts that engulfed the old church never healed. Marion Alderton, Alice Park, Josephine Duveneck and others never really forgave their fellow Unitarians. And there were others who didn’t formally resign from the church, but nor could they ever quite forgive. The old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto proved unable to deal effectively with the conflict between the pro-war faction and the pacifists.

Perhaps most importantly, though, the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto didn’t have a compelling vision for itself. For much of its history, it was little more than a social club that happened to own a beautiful little building. This was part of the reason they couldn’t overcome their conflicts — when a congregation is little more than a social group, with no big purpose, there is nothing larger to inspire people to move past the conflict. Because the congregation was little more than a social group, when Elmo Arnold Robinson came along and welcomed people of different classes and ethnic groups into the church, the long-time members didn’t even bother to engage with the newcomers. As a result, they were unable to retain the newcomers who could provide new leadership, and help pay the bills. Indeed, by the late 1920s the long-time members seemed to have lost interest in Unitarianism, and to have lost interest in figuring out how their Unitarian church could affect the wider community.

In late 1947, Rev. Nat Lauriat ran into a similar problem, with a new generation of Palo Alto Unitarians. Lauriat was the dynamic minister of the San Jose Unitarian church who drove up to Palo Alto each week to preach to the new Palo Alto Unitarian Society, and to help them get organized. He wrote to denominational officials that “the general feeling was to proceed with great caution, and just have a pleasant little group.” However, Nat Lauriat found younger Unitarians who “wanted more action and growth,” and with his encouragement, these younger Unitarians were the ones who took over leadership, and built a thriving new congregation on their vision of Unitarianism as a force for good in the world. Nat Lauriat challenged the Palo Alto Unitarians to think of liberal religion as more than just a social club.

This is a perennial challenge for any Unitarian Universalist congregation. It is a challenge that Palo Alto Unitarian Universalists face today. There is still a feeling among some of today’s Palo Alto Unitarian Universalists “to proceed with great caution, and just have a pleasant little group.” But when we hear the story of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, we find that proceeding “with great caution” and having “a pleasant little group” ultimately leads to decay and dissolution. It’s the congregations with a larger vision — the congregations that hunger for “more action and growth” — that grow and thrive, that nurture the growth of their members, and that ultimately change the world around them for the better.