Rolf and Possum want to donate to their congregation’s pledge drive. Problem is, they don’t have any money. Then Rolf comes up with an idea….

As usual, full text below the fold.

Continue reading “Possum and Rolf and the pledge drive”Yet Another Unitarian Universalist

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

Rolf and Possum want to donate to their congregation’s pledge drive. Problem is, they don’t have any money. Then Rolf comes up with an idea….

As usual, full text below the fold.

Continue reading “Possum and Rolf and the pledge drive”Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk known for popularizing the concept of “Engaged Buddhism,” has just died. (He died Jan. 22 in Vietnam, on the other side of the International Date Line, which was Jan. 21 here in the U.S.) He had been incapacitated by a stroke in 2014, and in 2018 finally received permission from the Vietnamese government to return to his home temple to spend his final days. His name is more properly rendered as Thích Nh?t H?nh, but I’ll use the more common romanization without tonal indications.

Thich Nhat Hanh is probably best known for his series of popular books on Buddhism. Worldcat lists the following titles as the five “most widely held works” in libraries: The Miracle of Mindfulness; Living Buddha, Living Christ; Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life; Anger: Wisdom for Cooling the Flames; and Being Peace. Nhat Hanh arguably did more than anyone else to popularize the concept of mindfulness in the West.

The book of his that I found most interesting, though, one to which I’ve returned a number of times, is The Sutra of the Full Awareness of Breathing (Parallax Press, 1988). This book includes Nhat Hanh’s translation of the ?n?p?nasati Sutta, along with his commentary on the text. This Sutra is no. 118 of the “medium length” sutras that have been collected into the Majjhima Nik?ya. (A later revised version of his translation is now freely available on the website of his Plum Village Buddhist community here.) Nhat Hanh translated the text into French, which was then translated into English; I found the English translation to be lucid, readable, and non-technical. I also liked his The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra; I find Buddhist scriptures difficult to understand, and Nhat Hanh’s commentary helped me understand a little bit about this complex text.

But I think Thich Nhat Hanh’s real impact as a writer and teacher was through his many popular books which give good sound advice for living life. I’ve read a little bit in some of his many books on mindfulness, and was impressed by the good common-sense tone of these books. Unfortunately, mindfulness grew into a fad, and big corporations have learned how to use mindfulness as an opiate to drug their workers into submission. But what Nhat Hanh said about mindfulness had nothing to do with submission to a corporate overlord. Quite the contrary: Nhat Hanh’s writings are permeated with the spirit of Engaged Buddhism, and mindfulness connects one fully with the fate of all beings; instead of quietism and retreat from the world, Nhat Hanh’s mindfulness moves us to become engaged in seeking justice.

If your corporate overlord forces you to do mindfulness — or if your school forces you to do mindfulness — try reading Nhat Hanh’s The Miracle of Mindfulness. You’ll find out that mindfulness is not a drug forcing you to submit to your employer or your school. Nhat Hanh used mindfulness as a way to advocate for peace during the long-running war in Vietnam. Mindfulness helped empower him to criticize both South Vietnam and North Vietnam, and also to stand up against U.S. involvement in Vietnam, at great personal cost. Mindfulness helped bring Nhat Hanh to the U.S. in 1966, where he helped convince Martin Luther King, Jr., to speak out against the injustices of the Vietnam War. In short, unlike the mindfulness that corporations and schools teach, which seems designed to ensure passive compliance with tyranny, Nhat Hanh’s mindfulness is designed to resist tyranny, oppression, and injustice.

I’m less interested in Nhat Hanh’s teachings on mindfulness — personally, mindfulness does nothing for my spiritual self — and far more interested in him as a teacher. Everyone I’ve talked to who saw him in person has said he was a riveting teacher. Apparently, his English skills weren’t great — I’m told Vietnamese and French were his main languages — but even through an interpreter his teaching was compelling. I get the sense that it was his presence as a teacher that most impressed those who went to hear him. This has been true of the best teachers I’ve known: there’s something about the way they move, the way they hold their bodies, it is their very being that teaches us. The best teachers, I think, cultivate their persons — or as we might say in the West, cultivate their souls — and it is this cultivation of the person which shines through in their teaching. While I never experienced Nhat Hanh in person, I can catch glimpses of this cultivated soul in his writings. I would unhesitatingly call him a brilliant teacher.

Our troubled world needs brilliant teachers like him, teachers who can empower us to stand up for justice and peace. Thich Nhat Hanh will be sorely missed.

I believe the UUA’s “Copyright & Permissions for Hymn and Reading Use in UU Worship” may incorrectly lists two hymns as public domain or fair use.

Jubilate Deo, hymn #393 — words and music are stated to be “fair use or public domain.” The words clearly are in the public domain. However, the music is covered by copyright. Hymnary.org lists Jacques Berthier as arranger, and shows a scan of a page from a recent hymnal, Ritual Song (2016), that give the following copyright information: “Taizé Community, 1990, © 1978, 1990, Les Presses do Taizé, GIA Publications, Inc., agent.” I think it’s pretty clear that this song should not be used in recordings without permission from the Taizé community.

Rise Up O Flame, hymn #362 — words and music are stated to be “fair use or public domain.” The earliest reference I can find of this song is in the book Sing Together published by the Girl Scouts in the U.S. in 1936; there, the song is “used by permission” and credited to the Kent County Song Book from 1934, which was printed in England for the Girl Guides. Sing Together credits the music to Christoph Praetorius, and it’s quite possible the music is by Christoph Praetorius, or more likely was arranged by someone else from his work. However, the English-language words are surely a translation or adaptation, and may be protected by copyright.

Both these songs have been widely reprinted and recorded, including by major publishers, so you can probably get away with including them in recordings of your congregation’s worship services. But if you want to record “Jubilate Deo,” you really should get permission from the Taizé community. As for “Rise Up, O Flame,” it seems that it was copyrighted at one point, but it’s not clear if the copyright applied to the U.S., and if so, whether the copyright was renewed; proceed at your own risk. Besides, as an ehtical issue, we should respect the moral rights of composers and authors.

This shows that there are indeed errors in the UUA’s “Copyright & Permissions for Hymn and Reading Use in UU Worship.” You have been warned.

Update: In their songbook Rise Up Singing, Annie Patterson and Peter Blood state that “Rise Up O Flame” is in the public domain. They are far more careful at researching copyright than the UUA, so I’m inclined to trust them on this. Plus, no one has sued them for copyright infringement in the decades that songbook has been in print. (And by the way, they do in fact credit “Jubilate Deo” to Jacques Berthier of the Taize community.)

I’m watching the case rates in Santa Clara County, where the Palo Alto congregation is located. The 7-day rolling average is over 4,000 — yikes, that’s high. On the other hand, preliminary figures for mortality seem to show a low death rate — probably due in part to the fact that 82.8% of county residents have been fully vaccinated (thought only 58.2% of eligible residents have received boosters). But on the other other hand (that’s three hands, if you’re keeping track), anecdotal evidence from health care professionals says that ICU beds are getting full again, and elective surgeries and procedures that require an overnight stay in the hospital are being postponed.

Obviously, this is not where we hoped to be. But rather than feeling discouraged, I suggest we consider this as another problem in planning. So, how do we plan for next steps in our congregations?

First, just to say the obvious — any plan we make has to be flexible, to account for changing circumstances.

Second, to say something else that’s obvious — we’ve discovered that the big thing that draws many people to UU congregations is the community. Sure, we like the theology, but the big draw is a chance to be a part of a community with shared values. And many people want to get a regular dose of UU community in person.

Third, something else that’s obvious — we’re gaining a pretty good sense of what’s safest, and less safe. It’s safest to do in-person gatherings that are outdoors, distanced (or small groups), and masked. It’s less safe to do indoors events, but some indoors events are still possible in some circumstances. Instead of saying, “Oh we can’t do what we used to do, waaah!” we probably need to start saying, “Gee, what are our present options for fun and engaging communal events?”

So here’s one obvious thing I believe we should be doing: we should be planning outdoors events. Whatever that might be: outdoors worship services, outdoors small group meetings, outdoors classes. (And I know what those of you are going to say who live where winters are really cold — you’re going to say this doesn’t apply to you. Well, my-sister-the-children’s-librarian, who lives and works in Massachusetts, is doing outdoors story time for kids in the winter; sure, her attendance is lower, but people still show up.) It’s true that not everyone in your congregation is going to come to outdoors events, but I suspect enough people are hungry for in-person interaction that it’s worth doing.

Another thing I believe we have to do: start planning like COVID is not going away. I would love it if COVID suddenly decided to go away next month. But it now looks like there’s a good chance that COVID is going to become endemic. If it has become endemic, then we’re going to have to learn to live with it. So maybe we should start thinking about one or more of the following: requiring proof of vaccination; think about shorter indoor worship services (e.g., 45 min., to limit time spent indoors); adding more worship services (so you can have more smaller indoors services); creating permanent spaces for outdoor programs where possible; improving ventilation in indoor spaces; and/or many other things.

Another obvious thing we should do: for our online offerings, keep improving community interaction. I’ve been noticing that many people are getting better at participating in online events — video conferencing is a learned skill. Similarly, I believe many of us are getting better at facilitating online communal interactions. In my own case, I’ve become much better at teaching online, and at facilitating online meetings — again, these are learned skills. As we continue to get better at participating in and leading online events, one of our goals should be improving community interaction.

One final thing I believe we should be doing: we should go easy on ourselves. Yes, the pandemic is probably going to kill off some UU congregations; but if you start thinking that way, you’re liable to either get tense and stressed out, or sad and filled with grief, neither of which is going to help keep your congregation going. Of course, getting overwhelmed and doing nothing is also not helpful; my point here is that we do need to do something, we just don’t need to be overachievers. My primary rule for congregational life has always been: if it’s not fun, let’s not do it. This still holds true during the pandemic!

I’m actually feeling pretty positive about congregational life in the immediate future. Yes it’s different from what I’m used to, and yes it’s hard to let go of a lifetime of past expectations, and yes change is annoying and difficult. But new possibilities are opening up, and I’m actually feeling quite positive about the future of our congregations.

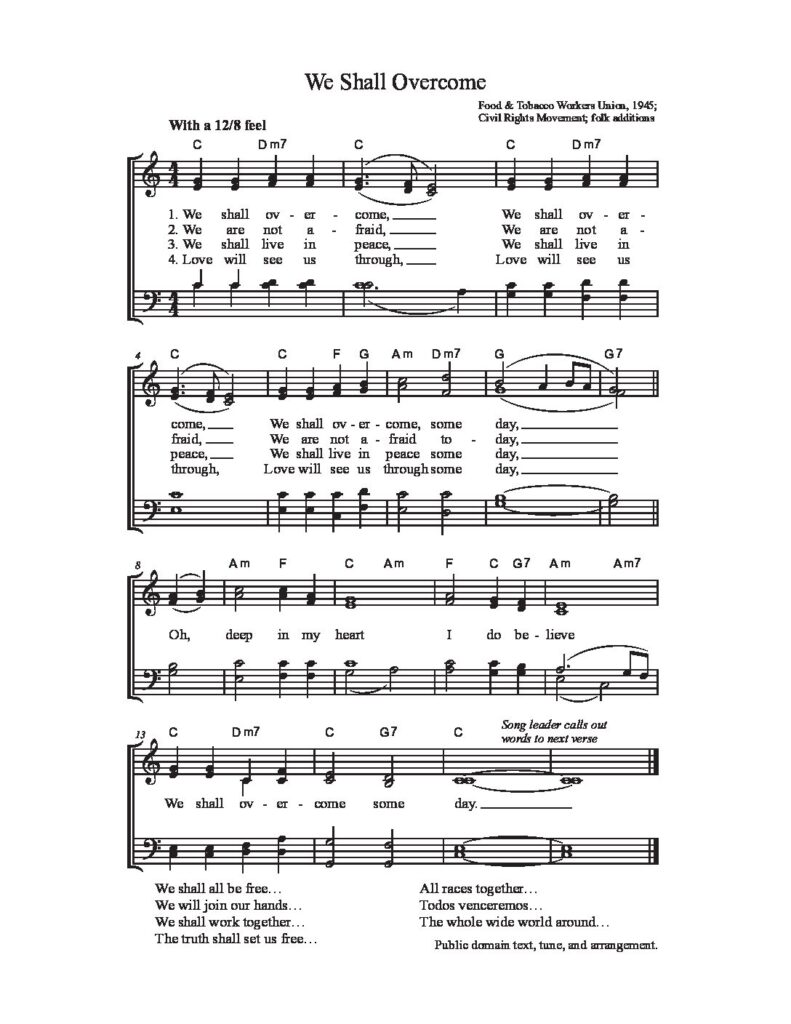

I recently learned that the song “We Shall Overcome” is now in the public domain, due to a 2017 court ruling and a 2018 settlement. A lawyer tells the whole story in some detail here.

The short version: In 2017, a federal court ruled that the tune, arrangement, and first verse of “We Shall Overcome” are in the public domain (We Shall Overcome Foundation v. The Richmond Organization, Inc., 2017 WL 3981311 [S.D.N.Y. Sept. 8, 2017]). In addition to the court ruling, the defendant and plaintiff subsequently entered into a settlement agreement which said, in part, that TRO would not “claim copyright in the melody or lyrics of any verse of the song ‘We Shall Overcome’”; furthermore, TRO agreed that all verses of the song were “hereafter dedicated to the public domain” (We Shall Overcome Foundation v. The Richmond Org., 330 F. Supp. 3d 960 [S.D.N.Y. 2018]).

This is very good news indeed. Sure, now the song can be used in all sorts of horrible advertising. At the same time, now you cannot be slapped with a royalty fee for using “We Shall Overcome” in your worship service, in the video that you made of some rally or demonstration, or in the audio recording of you singing at a coffeehouse.

Of course, just about all the piano or choral arrangements out there are copyright protected, including the one in the current UU hymnal. So here’s a very basic arrangement of “We Shall Overcome” which I’m releasing into the public domain; and hey, if you don’t like my version, it’s a public domain song so you can write your own! (I’ve changed a couple of the usual verses so they’re less ableist.)

By the way, I’m finding that it’s a good song to sing around the house now that we’re hunkered down because of the Omicron surge.

I just uploaded another batch of 26 copyright-free hymns onto Google Drive.

This collection of copyright-free hymns now includes a total of 63 hymns, with 38 copyright-free versions of hymns in the two current Unitarian Universalist hymnals, along with 24 other hymns and songs (including classics like “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” and “Michael Row Your Boat Ashore,” which really should be in our hymnals anyway). Not only are tune, text, and arrangement copyright-free, but the typesetting is as well, so you can project these or place them in online orders of service without a problem.

The “ReadMe” file in the Google Drive folder gives some information about each hymn, and also gives the corresponding number if there’s a version of the hymn in one of the UU hymnals.

In several cases, hymn texts now offer degenderized lyrics, for those who prefer to move away from binary gender options (e.g, for “The Earth is our mother,” the alternative “The Earth is our parent” is suggested). Eventually, I’ll offer degenderized options for all lyrics, but it takes — so — much — time to produce quality music typesetting that I can’t promise when I’ll get to it.

Whether you use these in your congregation’s online worship services, or at home, or around a campfire, I think you’ll find lots of fun and uplifting music here. I’d love it if you’d let me know where and how and if you use this music!

Update, 1/18/2022: Now up to 71 total hymns and spiritual songs, with 44 of them being copyright-free versions of hymns from the two current UU hymnals. List of hymns (with references to hymnal numbers, and notes on copyright status) below the fold.

Continue reading “More copyright-free hymns”Where do the words for the hymn “We Sing of Golden Mornings” come from? This hymn appears in the 1955 American Ethical Union hymnal We Sing of Life, and in the 1993 Unitarian Universalist hymnal Singing the Living Tradition. In the latter hymanl, the words are attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson, “recast 1925, 1950, 1990.”

But a quick web search shows that the phrase “golden mornings” does not appear anywhere in Emerson’s poetry. The same is true of several other distinctive phrases in the hymn: “flashing sunshine,” “heart courageous,” “earth’s great splendor,” etc. I can’t even figure out from which of Emerson’s poems this hymn might have been derived.

Eunice Boardman (Exploring Music, vol. 4, Holt, Rhinehart, and Winston, 1971, p. 26) attributes this as “words by Vincent Silliman from a poem by Ralph Waldo Emerson.” Well, maybe. But I can’t find any Emerson poem that even vaguely resembles this. Clarence Burley, in an essay “Emerson the Lyricist” (Emerson Society Papers, vol. 8, no. 1, spring, 1997, p. 5), says that as this poem “does not appear in the Library of America edition [of Emerson’s complete poems], I don’t know the extent of recasting and revising.” That’s a nice, polite way of stating my conclusion — that this hymn is Not Emerson.

(Oh, and to complicate matters more, the music attribution is also wrong. The tune is in fact from William Walker’s Southern Harmony, only slightly modified. But the harmonization in Singing the Living Tradition is most definitely not by William Walker, which raises the question: Who wrote the harmonization?)

Part Six of a history I’m writing, telling the story of Unitarians in Palo Alto from the founding of the town in 1891 up to the dissolution of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1934. If you want the footnotes, you’ll have to wait until the print version of this history comes out in the spring of 2022.

Part One — Part Two — Part Three — Part Four — Part Five

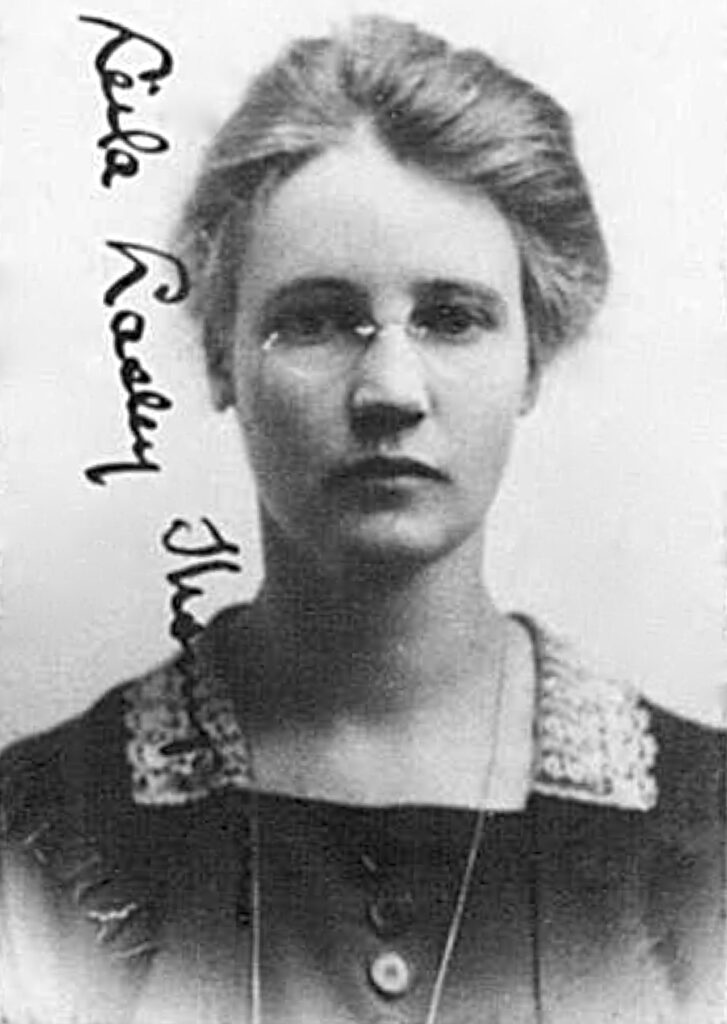

In late 1925, Elmo Robinson could look back on “four happy years, profitable to me, and I hope to the church.” But he had grown restive. He received a grant so that he could study for a semester at Harvard University in the first half of 1926. He found, or the church found, Leila Lasley Thompson to fill in for him while he was away. Thompson had married a soldier in 1918 who then was killed in action a few months later, leaving her a war widow. She then studied for the ministry at Manchester College, Oxford, England, a Unitarian theological school; was fellowshipped as a Unitarian minister by the American Unitarian Association; and pursued post-graduate study in 1925 at the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry.

Robinson departed at the end of 1925, leaving Leila Thompson in charge of the congregation. The congregation ordained her on Sunday, February 7, 1926. A month or so later, Robinson decided that he wasn’t going to return to the church. He apparently decided to pursue an academic career, although a note from him dated April 5, 1926, has a cryptic reference about protecting himself from “the charge of using this leave of absence as an opportunity of running away from an unpleasant situation without giving everyone a chance to be heard.” The “unpleasant situation” may well have been the long-standing conflict between the pacifist faction and the pro-war faction. Not even Robinson, with his skill and experience, had been able to heal that conflict.

After going east, Robinson never returned to Palo Alto — which sounds a little too much like Bradley Gilman’s departure from the church. In September, 1926, the church called Leila Thompson as the sole minister of the church. She was reportedly the first regularly ordained woman to serve a minister of a Palo Alto church.

Sadly, Leila Thompson received little support from the lay leaders. Sunday morning attendance dropped even more, from 34 in 1925, down to 27 in 1926, and then to 22 in 1927. Sunday school plummeted from 62 in 1925 down to 25 by 1927. The Young People’s Group continued to be active; Gertrude Rendtorff was still a Stanford student, and perhaps her continued participation kept that group going.

Alfred S. Niles, a lifelong Unitarian, moved to Palo Alto with his wife Florence, also a Unitarian, in the fall of 1927. When they arrived in town, Alfred and Florence sought out the Unitarian church. He found a church that was “still functioning, but rather feebly.” He was told that the church had once been active, “but the minister at the time of World War I had been a pacifist and conscientious objector [i.e., William Short, Jr.], and this had caused a split in the church from which it never recovered.”

Attendance got so low that the congregation tried moving the services to the evening, but that didn’t help matters. At the end of December, 1927, Leila Thompson resigned. It appears from the extant records that everyone became aware that there really wasn’t enough money to pay her salary any more, not even with the assistance the church still received from the American Unitarian Association. The church got Clarence Vickland, a student at the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry, to come preach to them in 1927-1928. Sunday morning attendance continued to drop, down to an average of 21, and by December, 1928, the Sunday school had closed “as there was not sufficient interest manifested to justify continuing the work.”

Finally, in 1929, the church stopped holding services altogether. Clarence Vickland wrote to the Women’s Alliance asking if they would like to host a visiting Unitarian minister on March 3, but they replied that “it would be impossible to get the congregation together.” 1929 was also the year that Karl and Emma Rendtorff retired to Carmel. With the Rendtorffs about to leave town, there was no real hope for the church. In May, 1930, Rufus Hatch Kimball reported to the Women’s Alliance that the Board of Trustees had turned the church building over to the American Unitarian Association. The church had finally dissolved.

The Women’s Alliance was declining, too. They continued to work on charitable projects — at their June, 1932, meeting, they worked on sewing for the Needlework Guild — but their numbers were shrinking. By May, 1930, the membership list had only nineteen names, and after Anna Probst Zschokke’s name appeared the notation, “Died May 30, 1929.” Like the church, the Alliance was slowly winding down and dying away.

The building sat vacant until early 1931. Then in February, 1931, Mary Engle reported to the Alliance that the American Unitarian Association had begun fixing up the building, and it was “now all in good repair and new locks have been put on the doors so that no invading hands could open them and…have access to Church of Alliance property.” By Easter Sunday, services were once again being held in the church, and Merrill Bates, the theological student who had been given charge of the church, had started up the church school once again.

The Alliance tried to help with the revived Sunday school, but grew discouraged with the tiny attendance, leaving Merrill Bates to manage on his own. Merrill Bates, Berkeley Blake, regional field secretary for the American Unitarian Association, and William S. Morgan, president of the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry, each preached to the church once a month, with Bates arranging supply preachers for the other Sundays.

Bates continued in the Palo Alto church until he graduated in spring of 1934. It’s hard to know how many of the old-time members still participated in the church. On March 27, 1932, Henry David Gray, who had become a member of the church in 1905, preached the Easter sermon. But most of the old members had either died, or moved away, or given up on the church. The Alliance held its last meeting on October 11, 1932, without even coming to a conclusion as to whether they should formally dissolve or not.

In April, 1934 — a month or so before Merrill Bates graduated from the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry — the American Unitarian Association put a “For Sale” sign up in front of the building. The building soon sold, for less than its mortgaged value. The American Unitarian Association retained possession of the organ, however, and gave it to the Unitarian church in Stockton, Calif. on permanent loan (Clarence Vickland was then the minister in Stockton). As Alfred Niles put it, there would be “no more organized Unitarianism in Palo Alto for several years.”

Indeed, there was no organized Unitarianism in Palo Alto for almost exactly thirteen years. In 1936, the liberal Quaker Elton Trueblood became the chaplain at Stanford University, and some Unitarians — like Alfred and Frances Niles — found Stanford’s Memorial Church a congenial place to go on Sunday mornings. Other Unitarians found other religious homes. Josephine Duveneck became active with the American Friends (Quaker) Service Committee, and eventually became a Quaker herself. Alice Locke Park also became a Quaker. Several Palo Alto Unitarians gave up on organized religion altogether.

Even for the Unitarians who went to hear Elton Trueblood preach each week at Stanford, there was no Unitarian Sunday school for those with children, and there was no Unitarian minister to officiate at rites of passage such as weddings and funerals. Perhaps more importantly for many, there was no Unitarian community of which to be a part. Then when Elton Trueblood left Stanford in 1945, there wasn’t even any liberal preaching in town.

In May, 1944, the American Unitarian Association organized the Church of the Larger Fellowship to serve Unitarians who didn’t have a nearby Unitarian church that they could belong to. This was a sort of mailorder church which sent monthly newsletters with sermons and other material of interest to Unitarians; it was, in a sense, an expansion of the old Post Office Mission. The Church of the Larger Fellowship grew quickly, and within three years, a dozen or so Palo Alto Unitarians had already joined.

In November, 1946, Alfred Niles saw a notice in the Christian Register, then the name of the denominational periodical, that the American Unitarian Association had appointed Rev. Delos O’Brian to be the the Regional Director for the West Coast, with an office in San Francisco. In February, 1947, Alfred Niles made an appointment to visit Delos O’Brian, who showed him two lists of names from the Church of the Larger Fellowship, one with a dozen names from the Palo Alto area, and another with a dozen names from San Mateo. Delos O’Brian was still undecided whether to organize a new Unitarian church in Palo Alto or San Mateo, and Alfred Niles later claimed that it was his visit that helped tilt the balance to Palo Alto. And on April 6, 1947, Delos O’Brian held an initial meeting to organize a new Unitarian group in Palo Alto. The Palo Alto Unitarian Society, as it was first known, grew quickly. Organized Unitarianism had finally returned to Palo Alto.

But even though many of the members of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto still lived in the area, most of them did not join the new congregation. Ruth and Everett Calderwood, who were only in their fifties, first claimed they were too elderly to take part, though later they did make financial contributions to the church. Katherine Carruth, who was then seventy-one, said she was sorry but she was too old to participate.

Edna True, on the other hand, who at seventy-two was older than the Calderwoods or Katherine Carruth, attended the very first meeting of the society, and became a member of the congregation. Clearly, while some Palo Alto Unitarians retained their enthusiasm for being part of a Unitarian church, others had lost all such enthusiasm. When Dan Lion arrived in Palo Alto as the first full-time minister of the new church, he made contact with some of the former Palo Alto Unitarians. He made an audio recording of his memories of calling on some of those former Palo Alto Unitarians, and while that recording has been lost, nevertheless, we can make a pretty good guess why those former Palo Alto Unitarians stayed away — the bitter conflicts that split the church, the incessant lack of money, the sense that they had been betrayed by some of their ministers and by the denomination, all contributed to drive these people away from any Unitarian congregation.

Other former Palo Alto Unitarians were happy to join the new congregation. Alfred and Frances Niles were central figures in the new congregation. Edna True was a member of the congregation up until she died, when she left a large bequest to the church. Rufus Kimball was integral in helping the new congregation claim its tax-exempt status. Ruth Steinmetz, a graduate of the old church’s Sunday school, joined the new church and remained active in it the rest of her life. Cornelis Bol, who had moved to Holland before the First World WAr, returned to Palo Alto in time to join the new congregation. Walter Palmer, who lived in Oakland by then, heard about the new church, and contacted them saying that he had been one of the charter members of the old church, and would like to be on the mailing list, though he wouldn’t be able to participate. Gertrude Rendtorff, living in Monterey, also heard about the new church in Palo Alto and asked to be on the mailing list.

Then too, as time went on, descendants of some of those former Palo Alto Unitarian families resumed a connection to the church. Guido Townley Marx, grandson of Palo Alto Unitarians Guido H. and Gertrude Marx, was married in the new church. Candace Longanecker, granddaughter of Errol and Laura Longanecker, was another grandchild who was married in the new church. And over the years, Dan Lion officiated at the memorial services of a handful of those former Palo Alto Unitarians.

The new congregation, renamed the Palo Alto Unitarian Church in 1951, was wildly successful. By 1965, they had three worship services each Sunday, and the Sunday school had some six hundred children enrolled. In less than twenty years, the Palo Alto Unitarian Church became one of the largest Unitarian congregations on the West Coast. So why did the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto die, and the new Palo Alto Unitarian Church succeed?

Partly, it was a matter of demographics and the economy. Before the Second World War, Palo Alto was a small town, probably too small to support a viable Unitarian church. After the war, both Palo Alto and the surrounding area gained population rapidly while at the same time the economy was booming. This meant the new congregation could grow quickly so it didn’t need to be subsidized by the denomination, and furthermore the new congregation could attract, and pay for, excellent professional leadership. But then when the new congregation faced financial stress in the late 1960s and early 1970s, due both to demographic decline and a declining economy, conflict erupted and membership and participation plummeted. Demographics and the economy are major influences on congregational growth and decline.

It was also partly because the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto was unable to integrate new leadership. It’s no coincidence that the congregation died within a year after Karl and Emma Rendtorff retired to Carmel. By the 1920s, the Women’s Alliance consisted solely of elderly and middle-aged women; the older women had not made room for young women to be part of the Alliance. As they aged, the small core of leaders that ran the old church was reluctant to share power with younger people.

Then too, the conflicts that engulfed the old church never healed. Marion Alderton, Alice Park, Josephine Duveneck and others never really forgave their fellow Unitarians. And there were others who didn’t formally resign from the church, but nor could they ever quite forgive. The old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto proved unable to deal effectively with the conflict between the pro-war faction and the pacifists.

Perhaps most importantly, though, the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto didn’t have a compelling vision for itself. For much of its history, it was little more than a social club that happened to own a beautiful little building. This was part of the reason they couldn’t overcome their conflicts — when a congregation is little more than a social group, with no big purpose, there is nothing larger to inspire people to move past the conflict. Because the congregation was little more than a social group, when Elmo Arnold Robinson came along and welcomed people of different classes and ethnic groups into the church, the long-time members didn’t even bother to engage with the newcomers. As a result, they were unable to retain the newcomers who could provide new leadership, and help pay the bills. Indeed, by the late 1920s the long-time members seemed to have lost interest in Unitarianism, and to have lost interest in figuring out how their Unitarian church could affect the wider community.

In late 1947, Rev. Nat Lauriat ran into a similar problem, with a new generation of Palo Alto Unitarians. Lauriat was the dynamic minister of the San Jose Unitarian church who drove up to Palo Alto each week to preach to the new Palo Alto Unitarian Society, and to help them get organized. He wrote to denominational officials that “the general feeling was to proceed with great caution, and just have a pleasant little group.” However, Nat Lauriat found younger Unitarians who “wanted more action and growth,” and with his encouragement, these younger Unitarians were the ones who took over leadership, and built a thriving new congregation on their vision of Unitarianism as a force for good in the world. Nat Lauriat challenged the Palo Alto Unitarians to think of liberal religion as more than just a social club.

This is a perennial challenge for any Unitarian Universalist congregation. It is a challenge that Palo Alto Unitarian Universalists face today. There is still a feeling among some of today’s Palo Alto Unitarian Universalists “to proceed with great caution, and just have a pleasant little group.” But when we hear the story of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, we find that proceeding “with great caution” and having “a pleasant little group” ultimately leads to decay and dissolution. It’s the congregations with a larger vision — the congregations that hunger for “more action and growth” — that grow and thrive, that nurture the growth of their members, and that ultimately change the world around them for the better.