Part Five of a history I’m writing, telling the story of Unitarians in Palo Alto from the founding of the town in 1891 up to the dissolution of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1934. If you want the footnotes, you’ll have to wait until the print version of this history comes out in the spring of 2022.

Part One — Part Two — Part Three — Part Four

A Fresh Start, 1921-1925

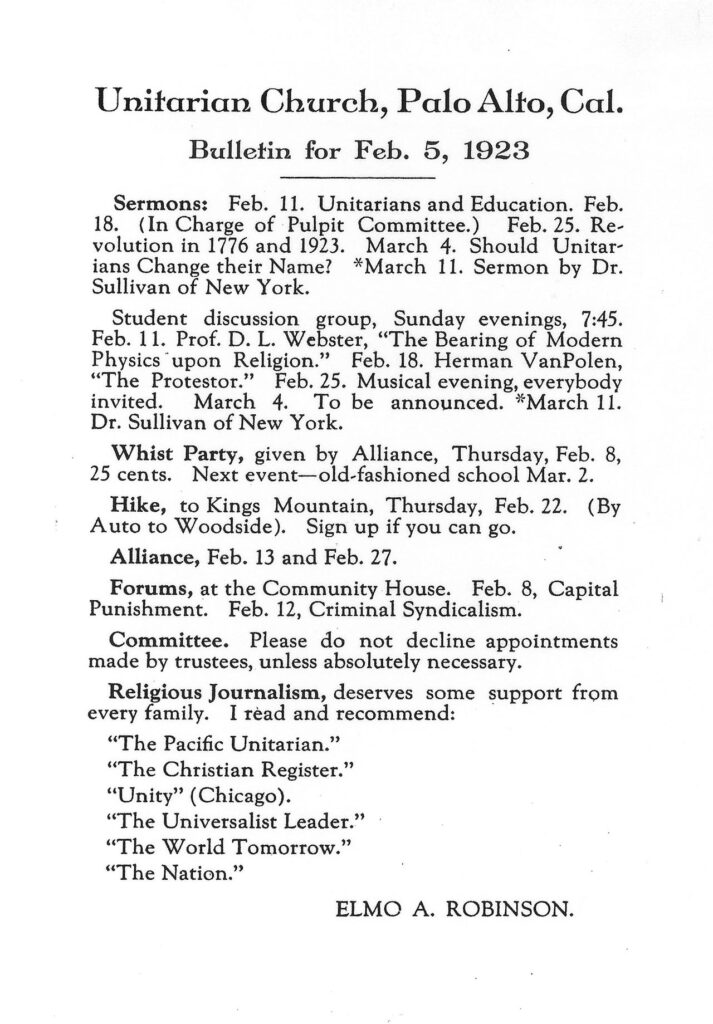

In November, 1921, Elmo Arnold Robinson, known as “Robbie,” arrived at the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto with his wife Olga and sons Kelsey, who was 9 months old, and Arnold, almost 5 years old. Robbie, ordained as a Universalist minister, had lots of experience in small congregations, plus he had just finished a two-year stint as the Director of Religious Education at a church in southern California. Olga was also licensed as a Universalist minister, although her time was taken up with her small children. It’s hard to imagine that the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto could have found a better match for their needs.

Not much happened in Robinson’s first year, except that Sunday school enrollment dropped still further. Emma Rendtorff had been the superintendent of the Sunday school in the 1920-1921 school year, and Sunday school enrollment crept back up to 31 children, but that was Emma’s last year as superintendent; her daughter Gertrude entered Stanford University in the fall of 1921, so Emma was no longer quite so invested in the Sunday school. In 1921-1922, Elmo Robinson’s first year, the church went through three Sunday school superintendents: Jessie Morton, who was William H. Carruth’s mother-in-law; William Ewert, a student at Stanford University; and Frank Gonzales, another Stanford student who served the longest of the three. With all that turnover, it’s not surprising that enrollment in the Sunday school dropped to 20, probably the lowest enrollment since 1908.

But Elmo Robinson had already turned his thoughts to religious education. In the summer of 1922, his essay “The Place of the Child in the Religious Education Community” was published in the Pacific Unitarian. This essay outlined a progressive philosophy of religious education that was tied to social reform:

“Every religious community believes that the future can be made better than the present. Every church, while cherishing certain ideals and methods of the past, must fire its young people with a vision of the future which will encourage them to devise new ways and means to realize it. Do you want world peace? World justice? The cooperative commonwealth?… All these things can be accomplished only by admitting children and young people to the full fellowship of the religious community as friends….”

Presumably, this essay repeated what had already been going on in the Palo Alto church. Bertha Chapman Cady was one of the teachers in the Sunday school in 1921-1922, and she involved the children in helping to run the class; one of her daughters, for example, became the class secretary. Children were becoming fully involved into the religious community of the church. The lay leaders seem to have found his vision a compelling one. The next school year, 1922-1923, the charismatic William Carruth agreed to be the superintendent of the Sunday school, and enrollment immediately shot up to 33 children.

The Sunday school proved to be the real success story of the next several years. Robinson managed to get Percy Erwin Davidson, professor of education at Stanford, to join the church, and in the 1924-1925 school year, Davidson became the Director of Teaching Methods for the Sunday school. He shared leadership of the school with William H. Carruth, who had the title Leader of School Worship. Sadly, Carruth died in December, but the Sunday school continued on nevertheless. In February, the church reported to the Pacific Unitarian that there were 69 pupils enrolled in the Sunday school. Elmo Robinson in his annual report was more conservative, putting the total enrollment at 53 pupils. In either case, it was the largest enrollment in the Sunday school since 1917.

For the next school year, 1925-1926, the church printed a professional-looking brochure announcing the program of the “School of Religion.” Percy Davidson was now called the Director of Religious Education, and Edwin H. Vail was the Leader of the School Worship. The brochure laid out progressive goals for their educational program:

“The purpose of this school is to teach religion apart from dogma. Our aim is to develop religious attitudes which will stand the test of life at its best, on a basis of accepted fact, by modern methods of educational procedure.”

This was, in fact, a continuation of the progressive educational program that Clarence Reed had championed, and parents responded with enthusiasm. In his annual report, Elmo Robinson reported that enrollment increased twenty percent, to 62 pupils.

Not all the pupils in the Sunday school were from upper middle class families, or families of Stanford professors. For example, Jean and Maurice Musy came to Sunday school nearly every week. Theirs was a solidly middle class family; their father Victor was a chef, and their mother Germaine was a hairdresser. During Robinson’s ministry, the membership of the church included middle class people like the Musy family, and even lower middle class people. One wonders what the long-term upper middle class church members made of Thelma Pickard, who joined the church in 1924, and by 1930 was working as a domestic servant. Some new church members weren’t even white Anglo-Saxons. Frank Gonzales, who became Superintendent of the Sunday school partway through the 1921-1922 school year, was the grandson of people from Mexico, and his father had worked as a janitor and teamster. Perhaps it made a difference that Frank was a student at Stanford. There was also Mercedes Pearce, whose mother had been born in Chile; here again, she was an educated woman who worked as a school teacher.

The Women’s Alliance thrived during Robinson’s tenure as minister. In May, 1925, the annual “List of Members” had 33 women on it. Admittedly, almost all of the Alliance members were older women; Olga Robinson, Elmo’s wife, was probably the youngest member, at age 41. Still, the Alliance had regular meetings and an interesting program of activities, and they remained strong institutionalists committed to furthering Unitarianism.

But most of the energy in the church during these years seems to have originated with Robinson. It was really Robinson who drove the revival of the Sunday school. In 1924, Robinson hired a part-time secretary and brought in Mary Brumbaugh, a theological student, to assist him. It was Robinson who reached out to the wider community in 1923, forming the “Get Acquainted Club,” where lonely newcomers could meet new friends. Robinson had the kind of personality that wanted to bring people together, across all kinds of divisions. In 1923, Stanley Manning, Director of Young People’s Work for the Universalists, visited the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto — at Robinson’s invitation. In reporting on his visit to Palo Alto, Manning said:

“[Robinson] is one who has stepped across denominational lines, both in his preparation for and in his work in the ministry, and believes them to be something like Elbert Hubbard’s definition of time: “a hypothesis based on an illusion.” There is no doubt in my mind that there will be more and more of this among liberal churches and ministers … in the direction of our Unitarian brethren [and beyond].”

Robinson’s ability to reach out to all kinds and sorts of people at first brought new energy to the church. In 1923, Sunday morning attendance rose to an average of 56, the highest attendance since the Clarence Reed years. But Robinson wasn’t able to hold the attention of the longterm members, and average attendance dropped to 37 in 1924. So Robinson asked members of the Young People’s Group, the group for undergraduates and graduate students, to attend services on Sunday mornings; many of them did so.

But even with half a dozen college students and graduate students, attendance slid still further, so that the average Sunday morning attendance in 1925 was just 34. Ida Belle Squires, who was one of those college students, later recalled, “The congregation was small and in need of money; I did not know most of them.” The long-time members simply weren’t interested in getting to know all these newcomers that Elmo Robinson brought in to their little church. Robinson could lead them to water, but he couldn’t make them drink.

I’m enjoying your Palo Alto and west coast histories as much or more than I enjoyed your down east tales of whalers, New Bedford, and UUs who lived closer to the hub.

Thanks Jim. I agree with you. There’s been so much focus on the East Coast history of Unitarianism and Universalism, that I’m kind of tired of it. But I’ve become fascinated with the history from the rest of the U.S. For example, I loved Cynthia Grant Tucker’s 2010 book “No Silent Witness” about the Eliot family in Oregon. I also loved Elmo Arnold Robinsons’ 1917 essay “Universalism in Indiana.” There are distinct regional differences in the way Unitarian and Universalist history played out in the Midwest, the South, the West Coast, and elsewhere outside New England. I’m really inspired by the different ways Unitarians and Universalists responded to regional cultural differences.