Another in a series of stories for liberal religious kids. This is a story about selfishness, and it also gives an insight into the supposed magical powers of Daoist priests. Source: Pu Songling, trans. Herbert A. Giles, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (London: Thomas De La Rue & Co., 1880).

One day in the marketplace, a man from the countryside was selling pears he had grown. These pears were unusually sweet with a fine flavor, and so the countryman asked a high price for them.

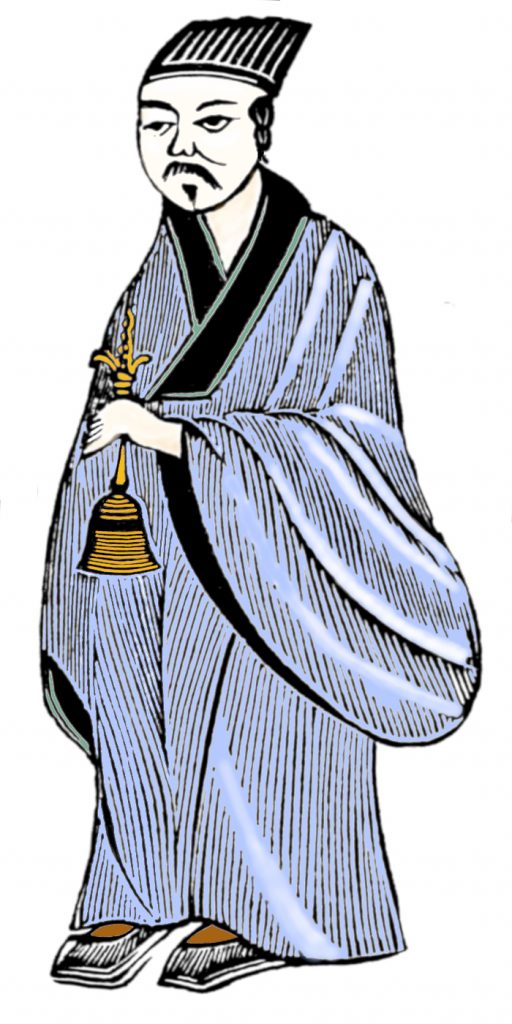

A Daoist priest, dressed in a ragged old blue cloak, stopped at the barrow in which the countryman had displayed these lovely pears.

“May I have one of your pears?” he said.

The countryman said to him, “Get away from my barrow, so that paying customers may buy my pears.” For the countryman knew that the priest expected him to give him one for nothing. But when the priest did not move, the countryman began to curse and swear at him.

The priest said, “You have several hundred pears on your barrow. I ask for a single pear, the loss of which you would not feel. Why then, sir, do you get angry?”

Several people who were standing around told the countryman to give the priest a pear that was bruised, or which had some sort of blemish, a pear that he could not sell anyway. If he would only do that, then the priest would go away. But the countryman was stubborn, and he refused to give the Daoist priest anything at all.

The beadle of the town, who was charged with keeping the peace and maintaining order, came over to see what was going on. This beadle saw that things were getting out of hand, so he purchased a pear from the countryman, and presented it to the Daoist priest.

The priest bowed low to the beadle, thanking him for the pear. Then the priest turned to the crowd who had gathered round, and said, “Those of us who are Daoist priests have left our homes and given up all wealth. So when we see selfish behavior, it is hard for us to understand it. Now as it happens, I have some pears with a very fine flavor, and unselfishly I would like to share them with you.”

Someone in the crowd called out, “But if you have pears of your own, why didn’t you just eat one of them? Why did you have to have one of the countryman’s pears?”

“Because,” said the priest, “I wanted one of these seeds to grow my pears from.” So saying, he ate up the pear that the beadle had given him. When he had finished eating, he took one of the seeds, unstrapped a pick from his back, and bent down to make a hole in the ground, four inches deep, with the pick. Then he dropped the seed into this hole, and filled it in with earth. Turning back to the crowd, he said, “Could someone bring me a little hot water, please, with which to water the seed?”

One among the crowd who loved a joke went into a neighboring shop and fetched him back some boiling water.

The priest poured the boiling water over the place where he had made the hole. Everyone watched closely, for though it seemed like a joke, Daoist priests were supposed to have knowledge of alchemy and magic and the mystical arts.

Suddenly the people in the crowd saw green sprouts shooting up out of the ground, growing gradually larger and larger until they became a tree. This pear tree — for it was, indeed, a pear tree — quickly grew in the spot, and sprouted green leaves, and then put forth white flowers. Bees were heard buzzing among the flowers, then the petals dropped, and before long the tiny hard green fruits had grown and ripened into fine, large, sweet-smelling pears which hung heavy on every branch.

The priest picked these fine pears and handed them around to everyone in the crowd. When at last everyone had a pear, and all the pears had been picked from the tree, the priest turned and with his pick he hacked away at the tree until, after a long time, he cut it down. Picking up the tree and throwing it over his shoulder, leaves and all, he walked quietly away.

Now this whole time, the countryman had been standing in the crowd, straining his neck to see what was going on, and forgetting all about his own business. When the priest walked away, he turned back to his barrow and discovered that every one of his pears was now gone. He then knew that the pears that old fellow had been giving away were really his own pears. And when the countryman looked more closely at his barrow, he saw that one of its handles was missing, for it had been newly cut off.

Boiling with anger, the countryman set off after the Daoist priest. But as he turned the corner where the priest had disappeared, there was the lost wheel-barrow handle lying next to a wall. It was, in fact, the very pear tree that the priest had cut down.

But there were no traces of the priest — much to the amusement of the crowd in the market-place, who watched the countryman’s rage as they finished eating their sweet, juicy pears.