1. HF wavelengths

“Although the ionospheric effects of solar eclipses have been studied for over 50 years, many unanswered questions remain,” according to HamSci.com, organizers of citizen science experiments designed to test the propagation of radio signals during the eclipse. I was not set up to actually participate in the citizen science experiments organized by HamSci.com, but I turned on one of my amateur radio transceivers to monitor high frequency transmissions during the eclipse; specifically, I monitored PSK-31 transmissions centered on 14.070 MHz, where I knew there would be a lot of activity.

Propagation was good before the eclipse started; at about 9 a.m. there was a fair amount of activity on 14.070 MHz, and I was receiving stations as far away as Colorado. As the eclipse progressed, I received fewer and fewer transmissions, and by about 10:20 (when the eclipse was at its maximum here in San Mateo), there were almost no readable transmissions. By now, the band is more active, although the stations I’m hearing are all on the West Coast.

My observations were completely unscientific, and it will be interesting to see what comes out of the data that the folks at HamSci.com are gathering during this eclipse.

2. Visible wavelengths

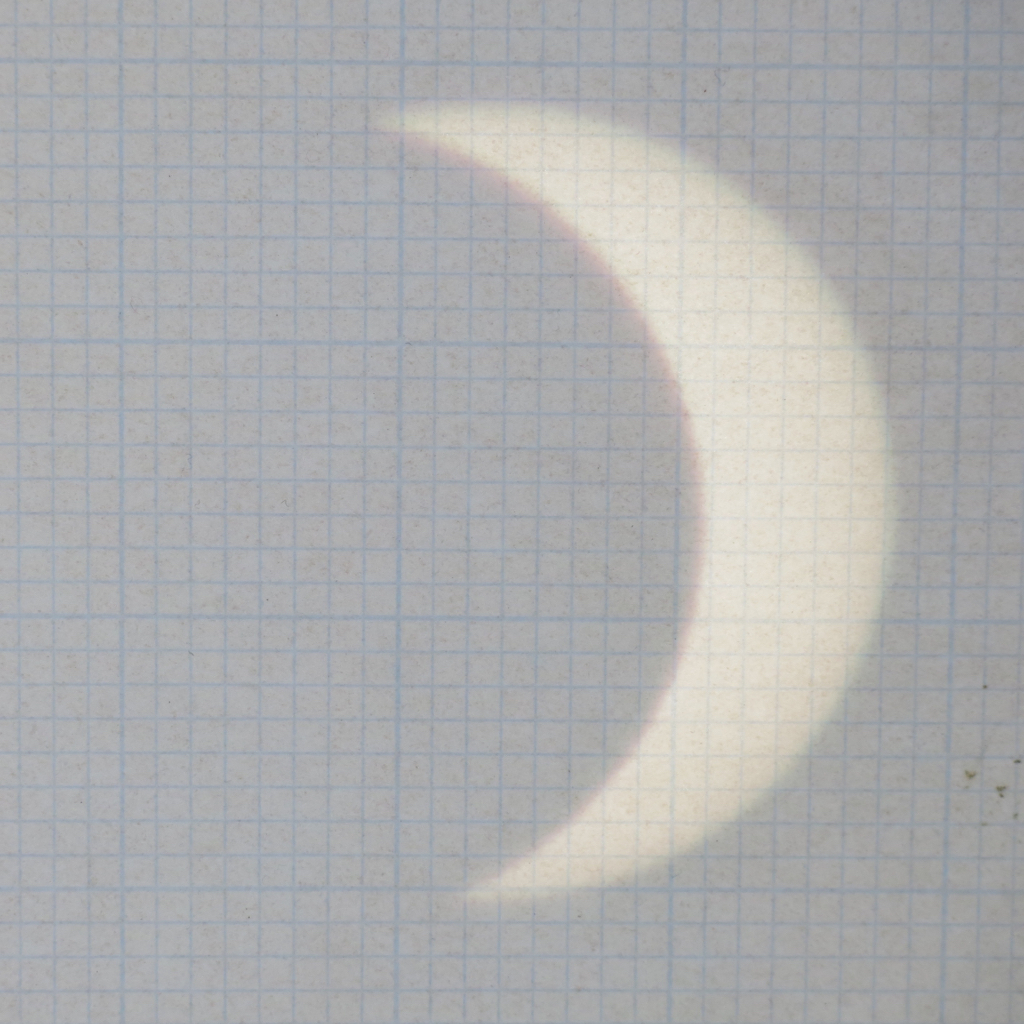

My plan was to project an image of the sun through binoculars mounted on a tripod. The sky was covered by stratus clouds (high fog) at 9 a.m., but by 9:45 the clouds began to break up and Carol and I got a few views of the moon’s shadow slowly moving over the sun’s disk. It became mostly clear by 10:20, in time for the maximum. Then it stayed clear, and I was able to watch the moon’s shadow slowly slide away from the sun.

One of the benefits of projecting the eclipse is that I could see the rotation of the earth as the projected image slowly moved as the sun changed its relative position in the sky. This was a good reminder that an eclipse involves relative movement of three astronomical bodies: sun, moon, and earth. And if I had had access to better optics, I could have projected a larger image and watched the movement of sunspots as well.

3. The emotional response

At about 10:20, when the eclipse was at its greatest extent, it was noticeably dimmer than it should have been. The light was about as bright as it would be around sunset — the difference being that the sun was high in the sky, so the shadows were short. It definitely felt a little eerie.

But mostly what I felt was a sense of wonder. This was the most astronomical fun I’ve had since watching the transit of Venus a few years ago.