Last night, Will texted me to say he and Linda were driving west on Interstate 80, and where was I? I texted him back saying that I was in Evanston. That’s where we are, replied Will. We arranged to meet for breakfast. Be sure to bring your Sacred Harp book, Will said.

The place that served breakfast in downtown Evanston was closed due to the holiday, so we wound up in the motel where Will and Linda had stayed. I will undoubtedly see Will and Linda at a Sacred Harp singing sometime this year, and when we do see each other we will talk about the same things we talked about at breakfast — how Will’s wife is doing, how Linda feels to have completed her Master’s degree — but how much fun it was to sit and talk as the result of the coincidence of staying in the same town on intersecting cross-country trips!

Linda had to go take care of her cats, but Will and I stayed in the breakfast room of the motel to sing a song or two. Will wanted to sing a traveling song, so we sang “The Promised Land”: “I am bound for the promised land. / Oh, the transporting, rapt’rous scene, / That rises to my sight, / Sweet fields arrayed in living green, / And rivers of delight.” We kept it soft and gentle, so as not to disturb anyone else, and when we had finished talked about how much fun it can be to sing with control and delicacy.

A woman thanked us for singing. We said she was welcome to join us, and she said she would love to; though she wasn’t much of a hymn-singer, even though she was a Christian. We sang “Wondrous Love,” thinking she might know the tune, but she didn’t, so she sight-read the harmony as best she could, improvising in places, in her mellow soprano voice. Then she said she knew “Amazing grace,” so we sang that in three parts. She asked where we had come from, and we told her about our coincidental meeting; she told us that she had lived in Evanston for many years, but now lived in Texas and was back for a visit. And with that, we all had to get going. I drove off feeling the best I’d felt on this trip so far.

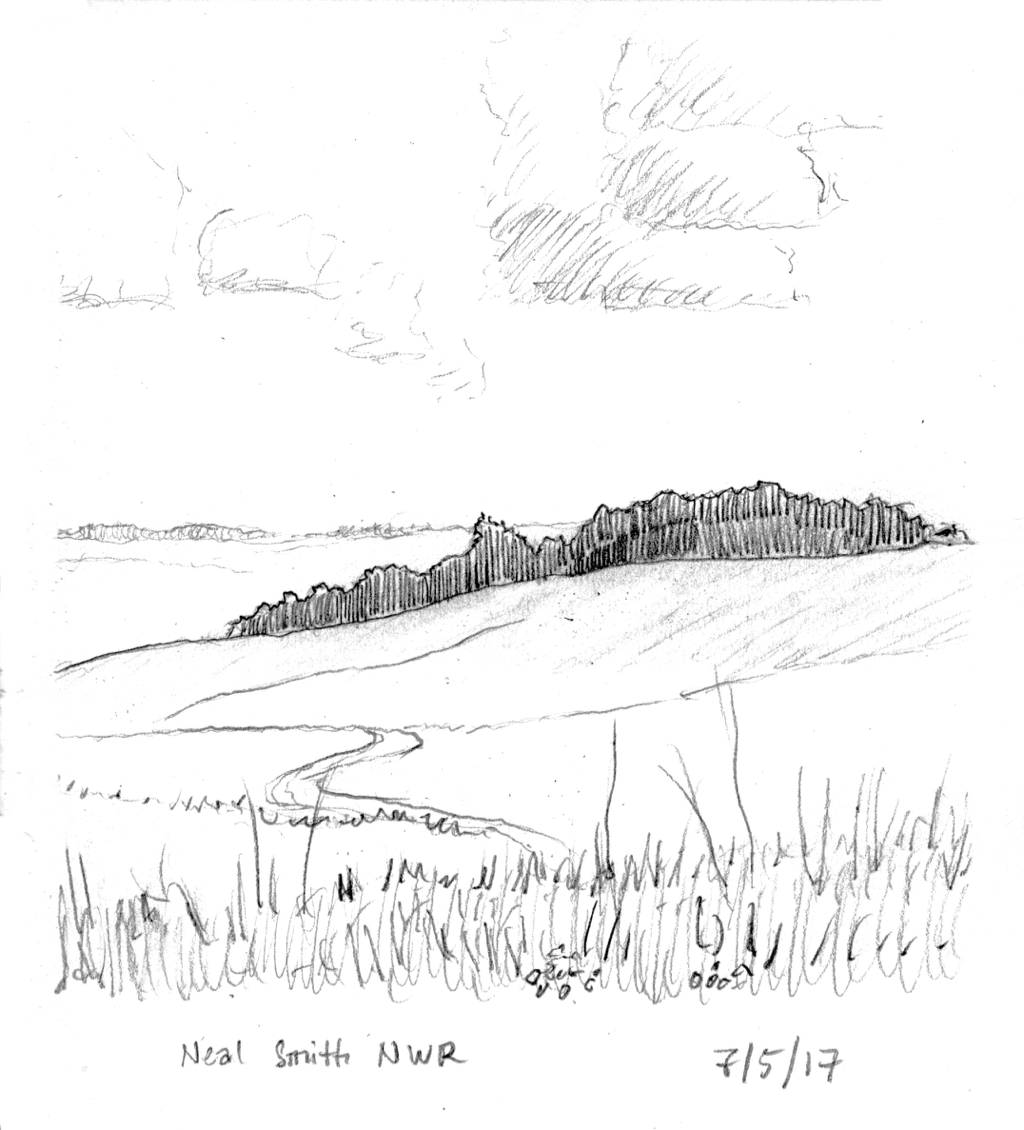

I stopped at Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge, and went for a walk near Six Mile Bridge. Within a quarter of an hour, I had seen what I had hoped to see: ten or a dozen Greater Sage-Grouse flushed noisily up and flew low over the sagebrush. I stopped to look at some Milkweed that was blooming and counted at least six different pollinators: bees, something that looked like a wasp, and a butterfly. (The photo below shows at least two different pollinators.)

The air was cool, and the sun was hot and bright and cheerful. A slight breeze mostly kept the mosquitoes and deer flies away. A Golden Eagle flew low over the trees on the other side of the Green River, driven to flight by the attacks of smaller birds. In the reeds at the edge of the river, a Moose (Alces alces) browsed the vegetation, chewing big mouthfuls of leaves from the bushes and trees.

Two Mountain Bluebirds flew along an irrigation ditch, looking spectacularly bright. A Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) skulked through some bushes, trying very hard not to be seen by me. Swallows swooped through the air, moving so fast I could only positively identify Cliff Swallows and Tree Swallows, though I thought I saw Northern Rough-winger Swallows and Violet-Green Swallows, too.

At last it was time to go, and regretfully I got in the car and starting driving east again. Some day I’d like to spend a week at Seedskadee; but not this year, I’m on a tight schedule. I drove the rest of the day, stopping for lunch and dinner, and pulled into Sidney, Nebraska, just in time to see the beginnings of a fireworks display. I watched it from the motel parking lot for ten minutes, then checked in to the motel, drawing the clerk away from the front door where she had been watching the fireworks. She put me in a second floor room that gave an even better view of the fireworks. I called Carol, who loves fireworks, and told her what I was seeing.

And then it was time for bed.