(Excerpts from a talk I gave at the UU Church of Palo Alto)

Over the past seven years, I’ve been exploring the religious diversity of Silicon Valley. This project started out because I was supporting the middle school class that goes to visit other faith communities. But over the years, it has taken on a life of its own, and has helped me better understand the role of religious organizations play in strengthening democracy, and it has also caused me to substantially revise my definition of what religion is.

So that’s what I’d like to do today: explore religious diversity in Silicon Valley, and maybe go on some interesting tangents.

And I’m going to start off by setting a limit around this exploration: I’m NOT going to look at solo practitioners of religion, or individual spirituality. This happens to be an important limit, since we are in an era of anti-institutionalism in which an increasing number of individuals refuse to identify with any organized religious community, even when they profess to have some kind of individual religiosity.

The role of faith communities in democracy

But I AM interested in exploring religiosity as it is expressed in a faith community, because I believe that faith communities can help sustain democracy. James Luther Adams, a theologian and sociologist, studied the role of voluntary associations — including faith communities — in democracies, and he concluded that they played a fundamental role in keeping democracy healthy. Among other things, he studied the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s (he even visited Nazi Germany himself in the mid-thirties), and found that one of the ways that the authoritarian Nazi regime came to power was by severely limiting voluntary associations. Thus Adams found that the right of free association is in fact critical to democracy; free association is critical at keeping authoritarianism in check.

This should be a major concern for us in the United States today. What we saw in the past two presidential administrations was a willingness to extend the powers of the presidency to an unprecedented degree; the rapidly rising use of executive orders is perhaps the most prominent example of this. The current presidential administration seems to be further extending the use of executive orders, further extending the powers of the presidency, and this administration seems to have tendencies towards centralization of power and decision-making in a smaller group of people. This should cause us to pay attention to the possibility of rising authoritarianism. This is coupled with a wider cultural tendency: some of the greatest popular culture heroes today are people in the business world who rule their business as authoritarian regimes, and these authoritarian business leaders are taken as positive examples to be emulated.

I find these trends and tendencies to be moderately alarming. Out of my alarm, I think, springs my deepening interest in voluntary associations such as organized religion. Although there is a lot of talk today about “resistance,” such talk strikes me as promoting a negative or passive approach, which is doomed to fail. Instead, I would like to promote positive responses to authoritarian trends; rather than merely saying, “Authoritarianism is bad,” I want to be able to say, “Here are some interesting and fun things we can do that strengthen democracy.”

And one of those interesting and fun things we can do to strengthen democracy is to celebrate the vibrancy of religious diversity, as it expressed in faith communities.

What is a “faith community”?

When I talk about “faith communities,” I mean something quite specific. A “faith community,” in my definition, is a voluntary association in which people have come together around matters of religion and spirituality. This definition is tailored for the U.S. context; it would work less well in certain European countries where there are still established churches funded by the government; and it would work less well in certain East Asian contexts where religion is less tied to voluntary associations.

But here in the United States, there is a strong connection between religion and voluntary associations, and defining a “faith community” as a voluntary association in which people have come together around matters of religion and spirituality — this definition proves to be useful and interesting.

At this point, you should be asking yourself: “What does he mean by ‘religion’ and ‘spirituality’?” It may look like I’ve been avoiding a firm definition of these terms, but as it happens, I do have a fairly precise definition in mind, a definition which works well in the context of a discussion of religious diversity, a definition which is primarily functional but not ontological or metaphysical. Therefore, from a functional standpoint, I’m not going to insist on a strong distinction between “religion” and “spirituality,” because in our democratic society we don’t have a distinction between these two terms that is widely accepted.

Here’s my functional definition: “religion” is what we point at when we say the word “religion.” This may sound like I’m avoiding the issue, but I’m not; I find that mostly when I point at something that looks like religion, most people will say, “That’s religion.” Sure, there are things that we point at which we can’t get wide agreement on as to whether they constitute religion or not. If I point at Scientology, some people will say, “That’s a religion,” and others will say, “That’s a massive con game.” So my definition does not have really crisp boundary lines. But mostly, when I point to a Christian church or a Jewish synagogue, or a Shinto shrine, or a Sikh gurdwara, or a Hindu temple, or Humanist gathering, or a Neo-Pagan ritual, most of us are going to say, “Yes, that’s something to do with religion.” We may go on to say, “That is a kind of religion that I think is disgusting or heretical or appalling,” but we acknowledge that it is religion.

Now I want to go a little farther, and place religion in a broad category that includes various kinds of cultural production. This broad category also includes the arts; and I would include organized sports as an art form, too. I find it helpful to think of religion as part of a broader category of “Arts and Religion,” and there has been some interested scholarly study of how certain art forms and certain sports activities look a great deal like religion.

To sum up, then: a faith community is a voluntary association that does religion, where “religion” is defined as what I point to when I say the word, and where religion is part of a broader category of cultural production that we can call “Arts and Religion.”

And I think you will find all this becomes very useful when we start looking at religious diversity. So let’s do that — we’ve got the preliminaries out of the way, let’s start looking at religious diversity in Silicon Valley.

Religious Diversity in South Palo Alto and Midtown

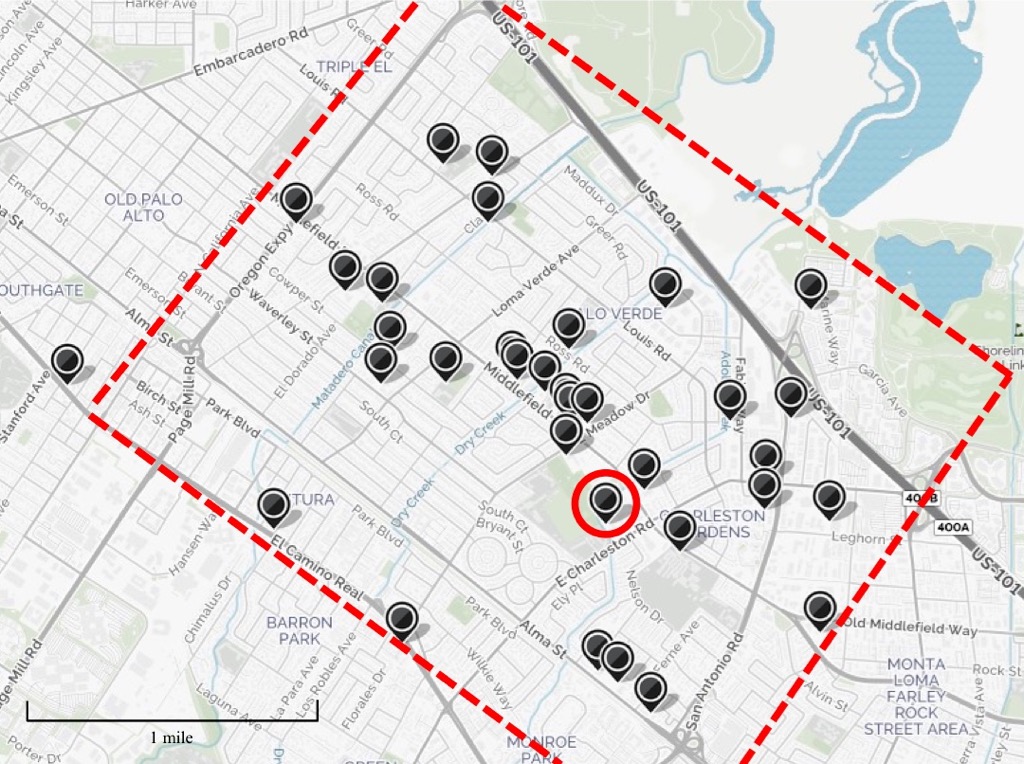

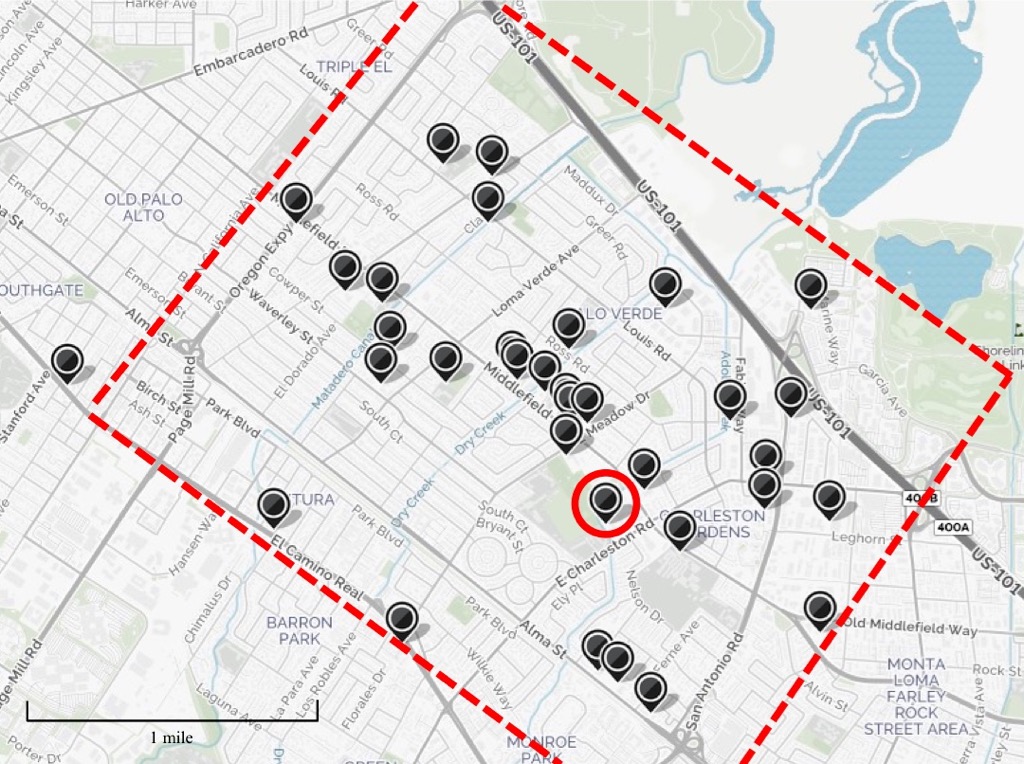

Let’s begin with our immediate neighborhood. Recently, I went looking for all the faith communities near our congregation, in a rectangle one mile wide by mile-and-a-half long, bounded by roughly by Oregon Expressway to the north, El Camino Real to the west, San Antonio Road to the south, and Highway 101 to the east. I came up with more than thirty faith communities that met regularly within this rectangle. I was astounded at this number — that’s a lot of faith communities located in such a small area.

Now let’s look at the religious diversity that is represented in this rectangle.

Denominational diversity

When Americans think of religious diversity, they usually think of how many denominations they can find. So we’ll start with denominations, though really the concept of denomination really works best for Protestant Christianity, and not so well for other types of faith community. Here are the denominations represented in this rectangle:

— 9 mainline Protestant Christian faith communities

— 1 Roman Catholic faith community

— 1 Orthodox Christian faith community

— 12 other Christian faith communities

— 1 Post-Christian faith community (that’s us)

— 4 Jewish faith communities

— 1 Muslim faith community

— 2 Buddhist faith communities

— 4 New Religious Movements (one of which would probably identify itself as Christian)

———

— 35 total denominations identified

The amazing diversity of Christian faith communities

Not surprisingly, the majority of these faith communities are Christian, as is true of American society as a whole: most of the faith communities in the U.S. are Christian. But don’t make the mistake of lumping together all these Christian faith communities as some kind of monolith. Christianity arguably has as much or more internal religious diversity as any of the major world religions; you could make a strong case that Christianity is as diverse or more diverse than either Hinduism or Orisa Devotion, and that’s saying a lot.

Compare, for example, an Orthodox Christian worship service, with its incense and chanting and elaborate decorative arts and music — compare that with the simplicity of Quaker silent meeting for worship. Or compare the social structure of Roman Catholicism, with its tradition of strong central authority, with the radically decentralized congregational polity of the Disciples of Christ. Or compare the cool emotional tenor of Lutheranism to the ecstatic worship of some Pentecostal groups. Compare the religious narratives of the Latter Day Saints, with the religious narrative told by a liberal Baptist church; the Latter Day Saints draw on the Bible and the Book of Mormon, whereas the Baptists are going to limit their narrative to what they find in the Bible.

Religious liberals and secularists often close their eyes to the religious diversity within Christianity by reducing Christianity to one statement: “Christians believe in God and Jesus.” This is a mistake on two levels. First, it trivializes the vast differences in Christian beliefs about God and Jesus. If you believe that all Christians believe the same things about God and Jesus, remember the amazing diversity of Christianity; so I’d challenge you to rethink that belief, because it doesn’t hold up.

There’s a second problem with reducing Christianity to one statement: “Christians believe in God and Jesus.” To do so reduces Christianity to a belief system, but no religion can be reduced to a belief system. The scholar Ninian Smart has come up with seven dimensions of religions. These seven dimensions are:

1. the practical and ritual dimension

2. the experiential and emotional dimension

3. the narrative dimension

4. the doctrinal and philosophical dimension

5. the ethical and legal dimension

6. the social and institutional dimension

7. the material dimension (which includes the arts and material culture)

So even if it were true that all Christians believe exactly the same thing about God and Jesus, you cannot reduce religion to the doctrinal and philosophical dimension, while ignoring the other six dimensions. Now it is true that you will find some religions emphasize one or more of these seven dimensions, and certainly Christianity emphasizes the doctrinal dimension. (Parenthetically, it is worth mentioning that most atheists are very similar to Christians, insofar as they emphasize the doctrinal dimension of religion.) But that being said, the person who is serious about investigating religious diversity needs to take into account all dimensions of religion — not just the dimensions that most concern them, but all dimensions.

For those who wish to study religious diversity seriously, a helpful analogy might be made between Christianity and arachnids. Now, there are people who are creeped out by spiders, and these people have some level of arachnophobia, that is, an irrational fear of spiders. Ssimilarly, there are secularists, atheists, and even some Unitarian Universalists who have some level of “Christian-phobia,” an irrational fear of Christianity.

When an arachnophobe sees a spider, they become immediately and irrationally fearful and say, “Ugh, a spider, step on it!” Compare the arachnophove to someone like Jack Owicki, a very knowledgeable amateur student of arachnids — when Jack sees a spider, he is able to appreciate it for what it is, classify it by family and genus and maybe even species, and determine its place in the wider ecosystem. If you want to be serious about studying religious diversity, you have to act towards Christians the way Jack Owicki acts towards spiders; in other words, don’t let your irrational fears get the better of you.

Diversity of race, ethnicity, language

Next, let’s consider the fact that many faith communities deliberately limit themselves in one way or another by linguistic, racial, and/or ethnic boundaries.

This is a troubling concept to many Unitarian Universalists, and other religious liberals. We like to think that our religion should be open to everyone, and one of our ideals is that we would like our faith community to reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of our immediate surroundings. When we do this, we are following the example of Protestant Christianity, from which historically we emerged. Protestant Christianity, like Catholicism and Buddhism, is proselytizing religion: it seeks to draw new people in. Proselytizing religions assume that everyone could join their religion, and they actively figure out how to incorporate new people. Compare this to a religion like Zoroastrianism, which does not actively seek out converts, and doesn’t have an established procedure for accepting converts.

Thus we find that different faith communities have quite different approaches to racial and ethnic diversity: some strive for diversity, some avoid diversity. And this also makes clear that we should not automatically assume that our own religious assumptions translate to other faith communities.

And in fact, it is useful and very interesting to look at faith communities in terms of what racial, ethnic, and/or linguistic groups they serve. Let’s start by looking at some of the racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity of faith communities in South Palo Alto:

— 2 faith communities aimed at Korean Americans (Bridgway and Cornerstone), including both Korean and English speakers

— 4 faith communities consisting primarily of those born Jewish, including many who speak or read at least some Hebrew

— 1 faith community aimed at Chinese Americans (Central Chinese Christian), apparent emphasis on Chinese speakers

— 1 faith community aimed at Russian Americans (Holy Virgin), apparent emphasis on Russian speakers

— 1 faith community aimed at Japanese Americans (Palo Alto Buddhist Temple)

— 1 faith community consisting primarily of Gujaratis (Hatemi Masjid)

— 1 faith community aimed primarily at blacks (University AME Zion)

— We also find 2 Pentecostal faith communities that are multiracial both in their ideals and in practice (Abundant Life and Vive Church).

As it happens, most of the remaining faith communities in South Palo Alto, including our own faith community, are Anglophone congregations that are mostly white racially. But we should remain aware that there are ethnic white faith communities, too; for example, there are still some Roman Catholic parishes that cater to one specific white ethnic or national group, such as Irish Americans or Italian Americans.

In short, we can categorize faith communities by which linguistic group, which racial group, and/or which ethnic or national group they predominantly serve. This becomes particularly important in certain religious traditions, such as Therevada Buddhism, where individual faith communities will serve one linguistic and/or national group, for example, a Cambodian Buddhist faith community or a Sri Lankan Buddhist faith community.

Further ways to categorize faith communities

Let’s take a step back, and review some of the ways we can categorize a given faith community:

We can say which broad religious tradition they consider themselves a part of.

Here in the U.S., we can often categorize by denomination.

We can categorize by dominant socio-economic class.

And by now you may well be thinking about other ways to categorize different faith communities.

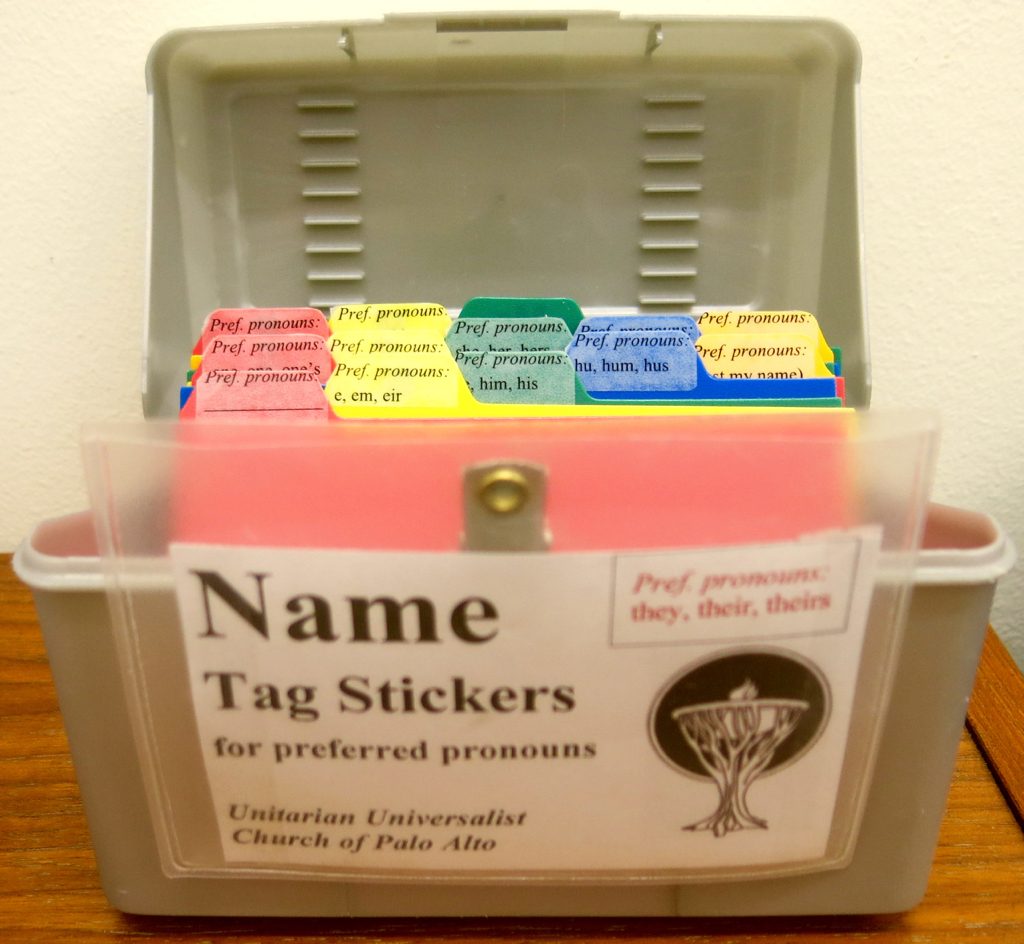

— Stance on same-sex relationships: If you know something about mainline Protestant denominations, you will know that local churches may differ as to whether they accept LGBTQ persons or not; so there might be two churches of the same Christian denomination fairly close to one another, one of which if fully accepting of LGBTQ persons, and another of which condemns homosexuality as a sin. You can find similar divisions on LGBTQ persons in Buddhist and Jewish and other faith communities.

— Worship style: We can also categorize faith communities by the style of their services. Are they informal, or formal? Are they friendly, or reserved? Look up faith communities on Yelp, and you will find them rated based on these categories.

And there are still other useful ways to categorize faith communities.

Finding religious diversity near you

All this is actually leading us to a super important question:

How do you go about finding faith communities near you?

Living here in Silicon Valley, of course we think that the best way to find neighboring faith communities is by doing a Web search. There are two main problems with this: first, the Web is generally not a trustworthy source of unbiased information about religion; and second, it can be hard to find geographically targeted information about religion on the Web. There is another problem: Some faith communities have no Web presence at all, either because they are trying to avoid notice, or because it just isn’t a priority for them.

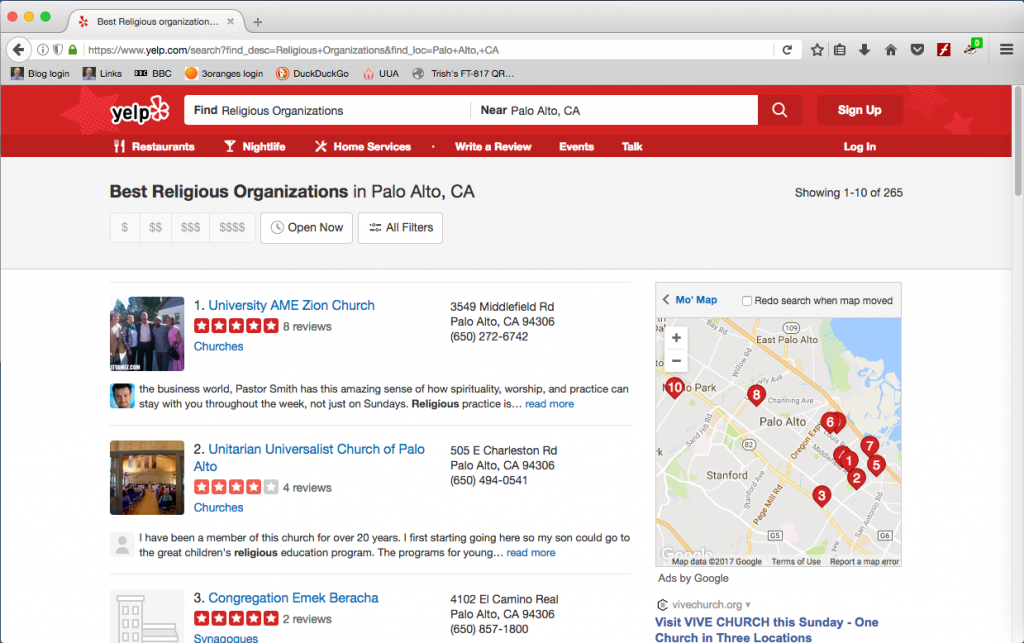

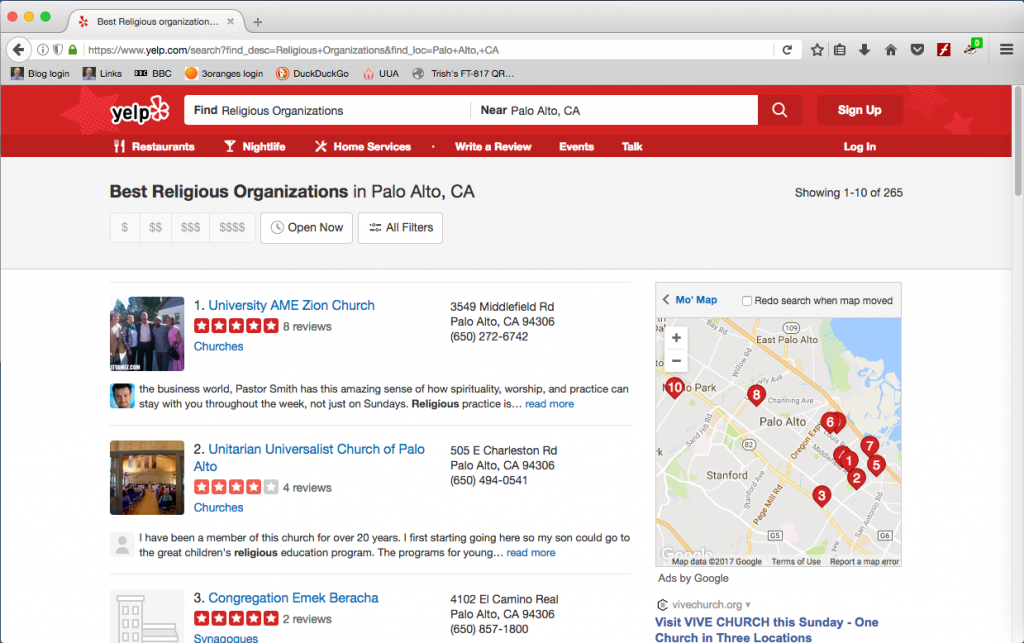

Fortunately, there is one pretty good source of localized information about religion on the Web, and that is the online review site Yelp.

Here’s how to generate a geographically restricted listing of fatih communities using Yelp.

Bring up Yelp.com on your Web browser. In the search box labeled “Find” at the top of the screen, type in “Religious Organizations.” In the search box labeled “Near,” type in your location. And voilà: Yelp generates a little map of your area, and a list of religious organizations that have reviews.

Now there are problems with Yelp: there are often duplicates of the same religious organization under slightly different names; the category of religious organization includes things that I would not consider a faith community; some faith communities are not listed on Yelp; their geographical restriction works only moderately well. But overall it’s better than any other online resource, and it’s a great starting point. Yelp may help you will turn up faith communities that do not have a Web page, or only an obscure Facebook page, faith communities that you might otherwise miss.

So: you can start your Web search with Yelp. But online resources will only take you so far, and should be supplemented with on-the-ground research, such a driving or walking in the area, and asking friends and neighbors if they know of any additional faith communities.