I had a slight but sharp headache when I got up, and it took me a few minutes to remember why: Evanston is about 6,750 feet above sea level, and I am not used to air that thin. Then I remembered that we were back in the Far West, where the air is much drier than the air in the eastern half of the continent, so I was probably dehydrated too. Coffee helped the headache go away.

Within an hour from the time we left Evanston, we were in the outskirts of Salt Lake City. We hadn’t driven through a city since we had to get through Chicago, and we did not like the thought of having to drive through Salt Lake. So we decided to go around it, up Interstate 84 to the north of Great Salt Lake, then down state highways to rejoin Interstate 80 in Utah.

As we left Interstate 84, a sign on Utah Highway 30 read: “Next Services 102 miles.” We drove past the occasional agricultural field, growing what appeared to be hay or alfalfa, and through open range (though we didn’t see any cattle). A sign declared that we were passing through the town of Park Valley, though we didn’t see much beyond a small cluster of houses and a Mormon church. A little later, we wound through another cluster of houses that a sign said was Rosette. People who live in these two communities have to drive forty miles or more to buy gasoline.

About halfway between Rosette and Grouse Creek Road, we pulled off the two-lane highway to look out over the basin of the Great Salt Lake Desert. We watched dark areas of rain fall from clouds fifty or a hundred miles away. We could see the glint of sunlight shining on the salt flats far to the south of us.

I stood in the middle of the highway to take a photograph of the highway and the plain sloping up to the mountains. There were so few vehicles I was able to stand in the middle of the road for several minutes and frame exactly the photograph I wanted.

Yet it didn’t feel lonely at all; it was just beautiful. But we had to keep driving west, so we got back in the car. We stopped briefly in Montello, Nevada, for something cold to drink; Montello boasted a couple of bars and a sort of general store that also sold gas. And in another half hour, we were back on the interstate.

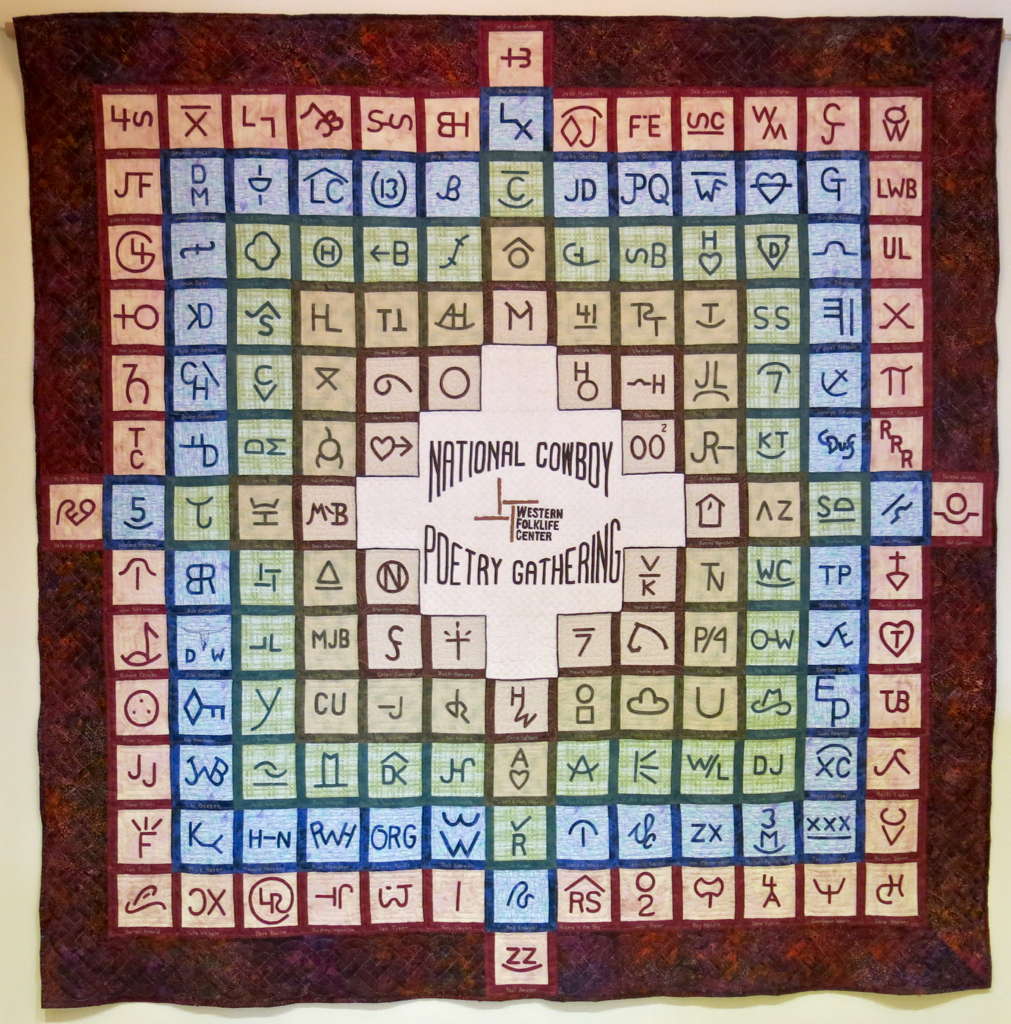

We made one more stop, at the Western Folklife Center in Elko, Nevada. They have one of the most interesting selection of books on the Far West, ranging from cowboy poetry to academic studies to just plain weird books. (In fact, one of my favorite books that I’ve bought at the Western Folklife Center is titled Living the in Country, Growing Weird, about life in a tiny town in north central Nevada.)

I got to talking with the man who was watching over the shop, and he told me that if I liked the books they sold, I should come in January to the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. It’s more than cowboy poetry, he said, there are workshops on hatmaking, and Basque cooking, and it’s lots of fun. And, he added, you can come by train, so you don’t have to drive through the snowy passes in January.

I’ve always wanted to come, I said, but it’s hard to get away from work in January. And that reminded me that I will be back at work on Monday, just two days from now. I love my job, but I’m not sure I’m ready to go back to work, not quite yet.