As you drive along Interstate 80, the people you meet in desert places, like in Winnemuca, tend to be friendly, tolerant of eccentricity, with a live-and-let-live attitude towards the world. The people you meet in mountainous places, like Laramie, tend to be outdoorsy and a little bit macho or macha, mountain-men and mountain-women who like to prove themselves. And the people you meet in the Midwest are courteous, pleasant, and just plain nice.

As anecdotal evidence to prove this theory, I offer the desk clerk at the Motel 6 in Winnemuca: friendly and tolerant even when he had to chase people out of the motel pool after the posted closing time, and on the edge of being eccentric himself. And I offer the clerk in the food coop in Laramie, who works in the ski industry, who obviously lives for his time outdoors, who was polite but uninterested in anything but outdoor sports. And I offer the waitresses as Ember’s Restaurant in Avoca, Iowa, who were unfailingly polite to me though I was the last customer of the night, the only customer in the place; they even chatted pleasantly with me and made me feel welcome while they were cleaning tables and mopping floors around me.

Of these three regions, where would I prefer to live? The idea of proving myself to the junior Paul Bunyans of the mountainous regions is not very appealing to me. I like the niceness of the Midwest, but I’m too much of a New Englander to trust constant niceness. But I’d like to live with the desert rats: I like friendly and tolerant people, and I’d fit in pretty well with the eccentrics.

East of Kearney, Neb., I saw a sign that said “Rowe Audubon Sanctuary Next Exit,” so I took the next exit. I crossed over several channels of the Platte River, turned right onto a gravel county road where a sign told me to, and soon pulled into the parking lot of the sanctuary headquarters, a stone’s throw from where the Platte River rushed by under cottonwood trees.

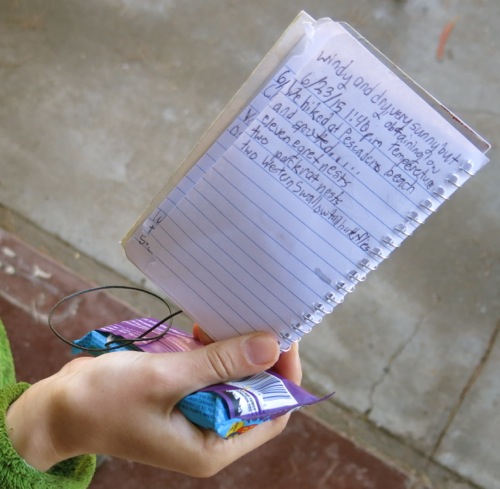

A staffer in the the headquarters building told me that they were experiencing a “high water event”: heavy snow in the Front Range in April, followed by heavy rains in May, caused high water in the Platte River in June. I found that the water was indeed high, right up to the main trail in places, and covering a number of small side trails completely.

It was hot — better than ninety five degrees, with humidity that made it feel hotter — and the mosquitoes were biting. But I hardly noticed. Northern Bobwhites were calling everywhere, and I saw several, running along the edge of a field, bursting into flight when I got too close, flying from a low perch in a cottonwood into the brush. I haven’t seen that many bobwhites since I was a child, and their calls brought me back to childhood, listening to them call in the fields behind our house: “Bob — white! Bob, bob, white!” over and over in the mysterious dark humid summer evenings.

It wasn’t just the Northern Bobwhites that drew my attention away from heat and mosquitoes. Dicksissels sang throughout the fields, a female Baltimore Oriole screamed at me when I got too close to her nest, a three-point buck stared at me from the edge of a corn field then sprang away, Tree Swallows zipped past just a few feet above my head. Overhead, high cirrus clouds refracted the sun into red, yellow, green, and blue; and since cirrus clouds are made of ice, this created a partial ice bow.

A big old rabbit stretched out in the shade with its legs splayed out fore and aft, so that its belly was on the cool, damp ground. It looked at me imperiously, daring me to come any closer, ready to spring into action if I did.

But I went back by the other path, because I suddenly realized how hot I was, and how good the air-conditioned car would feel. Besides, I had been walking around for two hours, and if I were to get to Avoca, Iowa, at a reasonable hour, I had better start driving.