A continuation of a documentary history of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

After the departure of Rev. Bradley Gilman, the congregation managed to get back on its feet, first with no minister, then with the experienced leadership of Rev. Elmo Arnold Robinson, a Universalist minister. But the financial situation worsened through the late 1920s, the congregation began to decline, and the Great Depression made it impossible to continue.

An Experiment in Palo Alto (1920)

[In the previous post, the excerpt from Josephine Duveneck’s autobiography told how the relationship between Rev. Bradley Gilman and the congregation grew strained. It is worth noting that Palo Alto was the last congregation that Gilman served. This chapter begins with an explanation of how the Palo Alto church experimented at having an entirely lay-led congregation. Edith Mirrielees asserts that the reasons for not hiring a minister were not financial, leaving us to conclude that Bradley Gilman soured the congregation on ministers.]

The Unitarian church in Palo Alto was established in 1905. From its establishment until the autumn of 1919, the church followed the way of most Unitarian churches, retaining a resident minister and supporting him with an enthusiasm that waxed or waned according to the circumstances surrounding the individual pastorate.

In May, 1919, the Rev. Bradley Gilman, at that time the incumbent, left Palo Alto for a visit to the Eastern coast. Some months later he sent in his resignation. When the congregation came together to consider the resignation, many of its members felt unwilling to begin the search for a new minister until an experiment had been made in conducting the church in another manner. For some years there had been a growing conviction among members of the Unitarian Society in Palo Alto that the presence of a professional minister was not necessarily essential to the continuance of their church or to its welfare, and after thorough discussion in congregational meeting it was determined to do without one, the pulpit to be tilled by members of the congregation and community or by visiting Unitarians. the other duties of the pastorate to be assumed by the congregation. It is worth noting that this decision was not reached because of money difficulties. The church at this time, though by no means wealthy, was in sound financial condition, without debt and with as many contributors as it had had during the previous year when a minister had been in residence. It should be noted, too, that the essential Unitarianism of the church is in no way affected by the change; the congregation is a congregation of Unitarians, but one wherein congregational government and responsibility is now carried a step farther than it has been before.

The attempt was at first frankly experimental. After four months of trial, it seems so far to have justified itself that there is at present no probability of a return to earlier conditions. Throughout the winter months, the pulpit has been regularly filled, often by speakers with a notable message, membership in the church and attendance at services have both materially increased, money has come in in quantity sufficient to meet all obligations and to make possible the establishment for next year of a scholarship at Stanford University, which it is the hope of the congregation to continue from year to year.

Rut these things, though they are encouraging, are only the outside results of the experiment. More important than any one of them is the effect of the change upon the relation of members of the congregation to the church and to each other. A new unity of purpose, an increased sense of fellowship, has been the most promising growth of the last few months. The presentation from the pulpit of many points of view 1ms promoted that tolerance essentially dear to Unitarians. The necessary sharing of responsibility has, as it is likely to do, increased the willingness to take responsibility. It goes without saying that the work has not been equally shared; as is the case in practically every congregation, one or two members have carried the heaviest part of the burden, but in very considerable number — a number much larger than was normally found under the old condition — have taken some part, with a resultant growth in actual neighborliness and interdependence.

It is by no means the thought of the Unitarian Society in Palo Alto that other bodies of Unitarians would necessarily be wise to follow in their footsteps. For any congregation, the wisdom or unwisdom [sic] of such an attempt depends upon the nature of the community in which the church is situated. It has to be a community which provides a fair number of thoughtful speakers; it has to be a congregation blessed with at least one member ready steadfastly to put the church’s welfare before his own, and neither of these things is easy to find. For Palo Alto, however, the experiment thus far has been promising enough to justify its further trial.

— Edith R. Mirrielees, The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 29, no. 5, May, 1920, p. 125.

[Note: Mirrielees was professor of creative writing at Stanford, and a teacher of John Steinbeck (Jeffrey Schulz and Luchen Li, Critical Companion to John Steinbeck [Facts of File: 2005), p. 301.]

———

Elmo A. Robinson Comes to California (1920-21)

[Note that as a Universalist minister, Elmo A. Robinson had to be fellowshipped as a Unitarian before he could serve a Unitarian congregation.]

Notice is hereby given that the Pacific States Fellowship Committee has received from Rev. William Maxwell, graduate of the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry, Rev. Elmo Arnold Robinson of the Universalist Church, and Rev. Thomas Louis Kelley of the Roman Catholic Church, applications for the certificate of commendation issued by this committee.

— The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 29, no. 9, October, 1920, p. 229.

Rev. Elmo A. Robinson has taken charge of the church in Palo Alto.

— The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 30, no. 11, December, 1921, p. 182.

———

The Place of the Child in the Religious Community

[Rev. Elmo A. Robinson emphasized programs for children and teens during his ministry in Palo Alto. This essay outlines his philosophy of religious education.]

Orthodox theory had it that children are born with such natures that, if they were left to themselves, total depravity would result. Liberal theory has had it that children are born with such natures that, if they were left to themselves, lives of goodness and usefulness would result. Consequently the orthodox churches have emphasized conversion, decision day, and all such methods of getting children out of the way of ruin and into the way of life. Once converted, they were then left alone. The only difference between this practice and that of liberals, is that in the latter ease the children were usually left alone from the beginning.

Both of these theories and their resulting practices are unscientific. Children are not horn with natures that guarantee either depravity or holiness, at least so far as this world is concerned. Rather are they equipped with certain complicated and conflicting instinct tendencies to behavior, which may find expression in either helpful or harmful ways. They do not need either to be mechanically converted or to he ignored. They need intelligent social guidance of their instinct tendencies into socially useful paths.

Some of this guidance can best ho given in the home, some in the school, some on the playground. Some can he given only in the church, only in a community of religious persons. The church is one of the many social agencies for the intelligent and sympathetic guidance of children.

It is well to recall that childhood is a great conserving force in society. Sometimes childless churches awaken to the fact that without a Sunday School today there will he no church tomorrow. This furnishes a motive for many of our workers. They say, “We love our church; we wish to perpetuate it; therefore we will recruit our ranks from the young.”

Society has always been doing this kind of thing. Witness the initiations in primitive tribes, the Hebrew synagogue, the mystery cults, Christian confirmation, and the fraternal orders. Man has been gripped by some great truth, some great mystery, some chosen way of life, and he has striven to conserve, to perpetuate this in the lives of the young.

In our own day we see this force of childhood being used by ultra-conservatives, who have sought to use the public schools as a means of combating socialism. evolution, unitarianism, [sic] and other dangerous heresies. Believing that changes of any kind are dangerous, they have tried to inoculate the minds of the young with a vaccine against new ideals and new experiments.

The church should not countenance such extreme use of the conserving force of childhood, but it may find legitimate ways of using it. Every religious community wishes to conserve something of the present for the future, and it is proper to do this through the guidance of childhood.

But childhood is also a progressive force. Hope as well as traditions have been passed on to the young by the aged. So it was with the hope for a Messiah; so it is with the hope for universal justice and peace. We need to transmit more, however, than our own ideals and methods. We want the world made better, but we must not insist on drawing up the plans and specifications by which the future generations are to work. We must teach our children to draw up their own plans and specifications.

Every religious community believes that the future can be made better than the present. Every church, while cherishing certain ideals and methods of the past, must fire its young people with a vision of the future which will encourage them to devise new ways and means to realize it. Do you want world peace! World justice? The cooperative commonwealth? A new and compelling world religion? Turn to your children. It is they who insure the progress of mankind onward and upward forever.

If the church is to guide children, if the church is to make use of children, the church must protect children. It must protect them against the industrial system, against disease, against habit-forming drugs, against crime and stupid amusements, against war. It must protect the boys and girls of all the world, of its own city, of its own neighborhood, of its own constituency.

All these things can he accomplished only by admitting children and young people to the full fellowship of the religious community as friends. We are too often afraid of our children. They think us stupid, and we think them unruly. We expect respect and discipline, when we do not respect them and can not discipline our selves. We must learn to be friends with our children.

Would you like to know the future? Would you like to control it? Look into the eves of your children and you will know it. Guide their lives into socially useful channels and you will control it. All the future loaders of the next generation are now boys and girls. All the future criminals are boys and girls. Education may not be able to change inheritance, but it can build upon it. The hope for a Messiah produced Jesus. It may be that God is even now raising up some new Messiah to lead the world aright. That leader may be a boy or a girl in your city, perhaps in your church.

— The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 31, no. 6, June-July, 1922, pp. 87-88.

———

Northern California Federation, Y.P.R.U., at Palo Alto (1923)

[In the 1920s, the Young People’s Religious Union, the program for Unitarian youth, included persons in their twenties and early thirties.]

On January 27th, the Northern Federation of the Young People’s Religious Union held a most successful winter social in the Parish Hall of the Palo Alto church. A box lunch supper was participated in as guests of the Palo Alto Young People. This was followed by a “Vodevil Supreme” in which eight church organizations were represented.

Dancing followed the entertainment. There were 83 persons present. 27 from Palo Alto; 19, Berkeley; 9, Alameda; 3 Oakland; 5, San Francisco; 5, San Jose; 3, Pacific Unitarian School; 13 visitors.

This is a most encouraging showing especially when one considers that well over 50 per cent of those present travelled over sixty-five miles; some in automobiles nearly 100 miles to make the round-trip and on a Saturday afternoon and evening through showers of rain. A remarkable spirit of keen interest and loyalty was in evidence. I wonder how many federations throughout the country could equal or excel this.

— C.B.W. [Carl B. Wetherell, Field Secretary], The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 32, no. 2, February, 1923, p. 49.

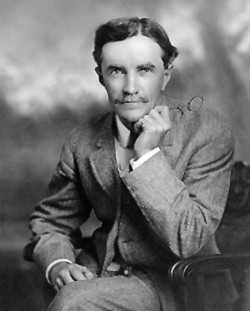

Above: William H. Carruth c. 1900

Memories of Prof. W. H. Carruth (c. 1924)

I enrolled in [W. H. Carruth’s] class in poetry writing. It was springtime, and he had his students meet under an oak tree on the expansive lawn stretching out from the front of the campus. He gave us a reason. After all, what better place was there to discuss the poems that we wrote than under an oak tree in the springtime? Perhaps there was another reason, for he was hardly ever prompt. He lived in Palo Alto. Once we were gathered under the oak tree, it made no difference if he were somewhat late because we were not going to leave such a pleasant spot. We could spot him coming from the distance, carrying his little satchel and hurrying to join us to discuss our poetry-writing.

In that poetry class was John Steinbeck. I already knew him from the English Club. We, in a way, competed against each other in our writing of poetry to see who would receive the better grade from Professor Carruth. When we got our grades, John got an A, and I received a B+. I said to John, “Now look, you’ve read my poetry and I’ve read your poetry. Do you think your poetry was any better than mine?” He said no. Then I said, “Well, can you explain, then, why you have received an A from Professor Carruth and I’ve received only a B+?” He said “Because you didn’t dwell in your poetry on the theme that would win an A from Professor Carruth.” I said, “Theme?” He said, “Professor Carruth has been strong on one theme. Some call it evolution, and some call it God. I wrote about God. I got the A.”

— Edward W. Strong, “Philosopher, Professor, and Berkeley Chancellor, 1961-1965,” an oral history conducted in 1988 by Harriet Nathan, The Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1992 (online version accessed October 12, 2013, 3:50 p.m.) http://www.oac.cdlib.org/ view?docId=kt8f59n9j3&query=&brand=oac4

Palo Alto Get-Together Club (1923)

[Rev. Elmo A. Robinson’s description of a social outreach program he began in Palo Alto.]

Palo Alto has a daily newspaper, The Times, which shows an unusual co-operative spirit toward the other social institutions of our city. Among other features it maintains a Forum Column, to which any person may contribute. In this column, about two months ago, there appeared a number of communications from various sources, complaining of the difficulty experienced by newcomers in making friends. At the suggestion of one who is not a member of our church, I extended an invitation, through the Forum Column, to all newcomers and to all who were lonely to come to our hall on April 7. Old-timers were also invited to come and help the idea along.

As a result the Get-Acquainted Club has been meeting weekly since that time. There is no formality of membership. There are no dues, although recently, at their own suggestion, those who wished made a contribution to cover the cost of light, janitor service, etc. There is no formality of introduction. Everyone who is interested is welcome, by virtue of the fact that he is, at least for the time, a citizen of Palo Alto. There are no officers, except an executive committee of three, whose chief duty is to decide the date of the next meeting. The program at each meeting is in charge of a committee, appointed by its predecessor at the previous meeting.

A good percentage of those in attendance is composed of newcomers. It is in no sense a church affair, and few Unitarians attend. All ages are present, from those in high school to the gray-haired. The number varies from 25 to 60, and the individuals vary from week to week. The program consists largely of lively group games which break the ice with hilarious laughter and promote acquaintance. There is usually a half hour of dancing at the close.

No one can prophesy how long this club will continue, but at present it seems to be meeting a real need.

— Elmo A. Robinson, in The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 23, no. 7, August, 1923, pp. 178-179.

———

A Humanist Club and Other Activities (1923)

Palo Alto.— During the past, three months the various organizations of our church have been so busy that no one has remembered to send in this report.

The Alliance has had three entertainments: a whist party in February, in March an old-fashioned school at which Dr. Jordan took the part of schoolmaster and the alliance members were pupils, and in April an excellent concert. Although one purpose of these entertainments was to raise money, they all added much to the friendly atmosphere of the church.

The Humanist Club has held its Sunday evening meetings regularly and has had several short hikes to nearby mountains and lakes. In March they gave a supper at the Stanford Union to the European students who toured America under the auspices of the National Student Forum. During the Easter vacation they spent a week at Carmel.

We have been fortunate in having Prof. E. F. Williams of the University of California, Dr. L. V. Harvey of Palo Alto, and Dr. Jordan preach for us. On one of these occasions Mr. Robinson occupied the pulpit of the Community Church at Los Gatos. Our student assistant, Mr. Bevier Robinson, preached on April 22 at Woodland.

Besides his regular work for the church, the minister has conducted two open forums at the Community House, one on the repeal of the Criminal Syndicalist Law and one for the Fellom Bill to abolish Capital Punishment. lie has also been instrumental in organizing a Get-Acquainted Club for the newcomers in Palo Alto. This club meets in our hall, and the number attending and the good spirit prevailing show that it is meeting a present need.

— The Pacific Unitarian, vol. 32, no. 5, May, 1923, p. 133.

———

School of Religion Opened at Palo Alto (1925)

Palo Alto, Sep. 28.— The school of religion of the Palo Alto Unitarian church was reopened yesterday morning at 10 o’clock. Rev. Elmo A. Robinson is pastor of the church, Prof. Percy E. Davidson is director of religious education, and Edwin H. Vail is leader of the school worship.

The purpose of the school is said to be to teach religion apart from dogma. “Our aim is to develop religious attitudes which will stand the test of life at its best, on the basis of accepted fact by modern methods of educational procedure.”

For younger people, stories, projects and other activities that introduce the pupil to religion are offered.

— from the San Jose Evening News, September 28, 1925, p. 2.

———

Connections with Stanford (1927)

Announcements: … Sunday, 6 p.m. Unitarian Young People’s Club meets at the home of Edward King, 144 Kingsley St. Paper by Miss Gertrude Rendtorff on the “Meaning and Sanction of Religion.” Discussion.

— Stanford Daily, vol. 70, no. 31, November 11, 1926, p. 2

Palo Alto Unitarian Church Plans Young People’s Sunday

The Unitarian Church of Palo Alto will celebrate its annual Young People’s Sunday this week-end. The entire church service will be in the hands of the young people who will give the talks, readings, and prayers. Margery Blackwelder will give the solo. Many Stanford students will take part in the service. Young People’s Sunday will be celebrated in Unitarian churches throughout the country on this day.

— Stanford Daily, vol. 70, no. 64, January 21, 1927, p. 1.

At the Monday morning chapel service at 7:50 o’clock, Mrs. Leila L. Thompson, of the Unitarian Church in Palo Alto, will be the speaker.

— Stanford Daily, vol. 31, no. 54, Thursday, May 12, 1927.