I’ve been trying to figure out why I’ve grown so interested in the multimedia curriculum kits produced by the Unitarian Universalist Association from 1964 to about 1990. I was first attracted by the integration of texts, audio recordings, and visual materials. But I realized I am also attracted by the existential educational philosophy. And I am attracted by the experimental nature of many of the curriculum kits.

First, some historical background:

In “Unitarian Universalist Religious Education: A Brief History,” by Elizabeth Anastos, 1981, from the book In the Middle of a Journey: Readings in Unitarian Universalist Faith development (ed. Richard Gilbert), Anastos tells the story of how the UUA came to develop the multimedia kits:

“The Unitarians and the Universalists had merged to form the Unitarian Universalist Association in 1961 and commissions had been appointed to study the needs of the new Association in six different areas of congregational life. Commission III, Education and Liberal Religions, reported its observations and recommendations with those of the other commissions in The Free Church in the Changing World in 1963. The Commission was supportive of the experimental [experiential?], developmental philosophy of the New Beacon Series. It outlined what it saw as specific needs in each age group and suggested that more emphasis should be placed upon the following in curriculum: ethics, Unitarian Universalists ideals, theology — be it humanist or theist — freedom and responsibility, the natural order, and social relationships.

“It stressed the need for better scholarship in the preparation of biblical and historical materials, for better worship materials for children, and for more teacher training materials.

“One of the members of that commission, Hugo Holleroth, became the next director of curriculum development. … Holleroth, formerly a Congregational minister, had served our Unitarian Universalist church in Paramus, N.J., as minister of religious education, and had most recently been Professor of Religious Education at St. Lawrence Univerity’s Theological School in Canton, N.Y.

“Holleroth, in the educational tradition of Dewey, and in the existential theological framework of Tillich, produced religious education materials to meet the needs of the 1970s. … In response to Commission III’s recommendations, the first materials were in the subject areas of ethics (Decision Making, Freedom and Responsibility); culture studies (Man the Culture Builder I & II, Human Heritage I & II); social relationships (About Your Sexuality, The Invisible Minority); knowledge and meaning (Man, the Meaning Maker, Person to Person); personal religious and emotional development (The Haunting House); religious heritage (Focus on Noah, Adventures of God’s Folk); and Unitarioan Universalist Heritage and Ideas (Disagreements Which Unite Us, Experiencing, Believing, and Celebrating, and Our Ways of Relating).

Next, a look at the existential educational philosophy underlying the multimedia kits:

Anastos claims that Holleroth’s curriculum kits were rooted in a Deweyan educational tradition. I’m not sure that’s entirely true. Certainly Holleroth developed curriculum kits that focused on addressing social problems, strengthening democracy and democratic institutions, and ongoing evolution and growth of society. But I believe Holleroth’s curriculum kits focus more on the search for meaning in a potentially absurd world; Holleroth had more in common with the humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers than with Dewey (and indeed, one of Carl Roger’s books is included in one of the curriculum kits).

Since he was primarily an existentialist educator, Holleroth was more interested in the foundational religious question “Who am I?” — than in the question “What ought I do?”, the foundational religious question beloved of progressives. Of course Holleroth expected that once persons answered the question “Who am I?” they would discover that part of who they are is a person who changes the world for the better. But if he had to choose between the two questions, “Who am I?” would be his first choice. For the record, some of the other foundational religious questions considered by our religious tradition include: “What is the ultimate nature of reality?” and “What is the final destination of humanity?” — but Holleroth gave those questions lesser importance in his curriculum development.

Holleroth’s most important predecessor in UU curriculum development was Sophia Fahs. Although usually considered as having a progressive educational philosophy, Robert L’H Miller has argued in “The Educational Philosophy of the New Beacon Series in Religious Education” (doctoral dissertation, Boston University, 1957), that the curriculum books that Fahs developed for elementary grades were grounded in an essentialist educational philosophy. As an essentialist, Fahs believed in transmitting a certain body of religious knowledge to children: who Jesus was, the grand sweep of the Bible story, creation myths — all these were topics that Fahs felt children needed to know about. A curriculum developed under Fahs’ direction was more likely to answer the question “What is the ultimate nature of reality?”; and her answer was grounded in the theology of religious naturalism.

Thus, Holleroth’s educational philosophy was a distinct departure from that of Fahs. I would also argue that he was our only major religious educator who held an existentialist educational philosophy. Most of the multimedia kits were never very well received, and their existentialist educational philosophy helped explain why. At the same time, Holleroth oversaw the development of two of the truly great UU curriculums: About Your Sexuality and The Haunting House. Both these curriculums are grounded in an existentialist philosophy, and therein lies a good deal of what continues to make them exciting and interesting.

As I look for a way forward, a path out of the gray suburban landscape of today’s competent but boring curriculums, I find myself attracted to the colorful, exciting, and — yes — chaotic urban (or is it wilderness?) landscape of Holleroth’s existentialist curriculums.

Finally, a list of the multimedia era curriculum kits, from 1968-1989. The descriptions come from the Leader’s Guide of Disagreements Which Unite Us. Lists of instructional materials come from my research in Meadville/Lombard Theological School’s archives:

Decision Making, Clyde and Barbara Dodder, 1968

gr. 5-8

“Designed to help fifth through eight graders come to grips with the complex choices they face every day, and the even more complicated decisions they will have to make in the future….”

— Leader’s Guide

— Visual resources including photographic slides, printed color images, comic books, black-and-white photographic prints, reproductions of artworks, etc.

— “Ethics Game”

— Cards for decision-making activities

Above: Leader’s guide from “Decision Making,” from the collection of Meadville/Lombard Theological School

Man the Meaning Maker, Jane Latourette, 1969

ages 9 and up

“Helps young people, ages nine and older, to examine human perception. Perception is defined as the mind-body’s interpretation of what one’s senses tell him [sic].”

Man, the Culture Builder (in two parts), Walter Bateman, 1970

gr. 3-8

“Designed to help third though eighth graders understand and appreciate the diversity of culture within the human community. To help children to a discovery of what a ‘culture’ is, Part 1 explores, extensively, the way of life of the Navajo Indians prior to 1890. … To review and enhance the conceptual tools developed in Part I, Part II opens with a glimpse into the culture of the Kung bushmen, who roam Africa’s Kalahari desert. After a brief exposure to this second non-technological culture, students are encouraged (and able) to apply some of the methods anthropologists use to a study of their own culture…. ”

— Leader’s guide

— Audio recordings on flexible vinyl discs

— Visual resources including large-scale map, photographic slides, film strips

— Several story books

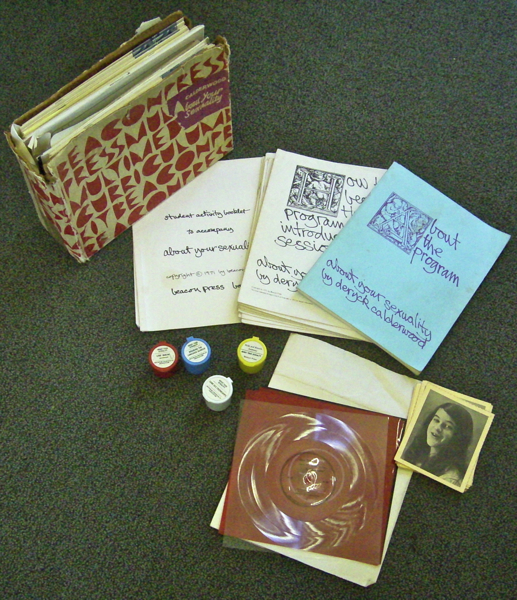

About Your Sexuality, deryck calderwood, 1971

gr. 7-9

“A highly flexible collection of multimedia resources (with accompanying leader’s guides) designed to help young people of junior high age and older, as well as adults, obtain frank and accurate information about sexuality.”

— Leader’s guide

— Sessions plans bound into several booklets comprising one curriculum unit each

— Student workbooks

— Visual resources including filmstrips (the 1978 revision substituted photographic slides) and photos of young people

— Resource books

— Audio recordings on 33-1/3 r.p.m. “flimsies” records (the 1978 revision substituted cassette tapes)

Above: Original 1971 edition of the “About Your Sexuality” kit, incomplete, from the curriculum library of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto. Clockwise from top left: Curriculum box (damaged), student worksheets, session plans, leader’s guide, photos of young people, “flimsies” (records), filstrips

Our Human Heritage (parts I and II), Joan Goodwin, 1971

gr. 3-6

“An adventurous approach to the story of evolution.”

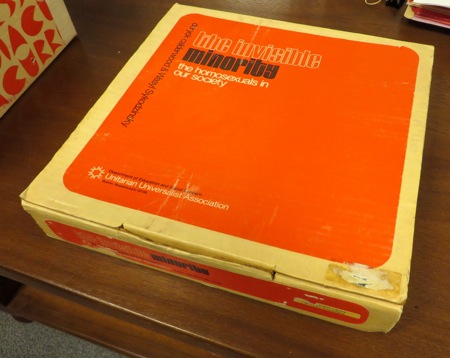

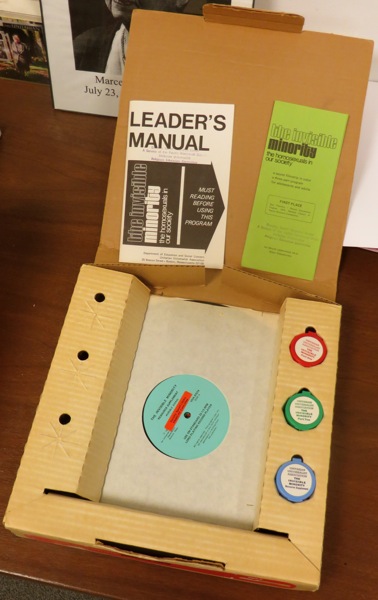

The Invisible Minority: The Homosexual in Society, deryck calderwood and Wasyl Szkodzinsky, 1972

Adults and teens

“Has been developed for use with adolescents and adults in response to the need for education concerning homosexuality.”

— Leader’s guide (24 pp. pamphlet)

— Long-playing records

— Film strips

Above photos: “The Invisible Minority,” curriculum kit box (top) and kit materials (bottom), from the collection of Meadville/Lombard Theological School

Person to Person Communication, Jane Latourette, 1972

gr. 7 and up

“Helps young people of junior high age and older explore interpersonal communication and develop language use from common speech into a conscious, effective tool for making meaningful contact with others.”

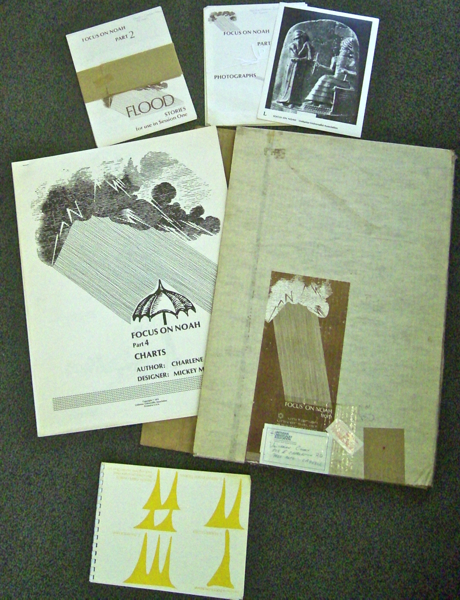

Focus on Noah, Charlene Brotman, 1974

ages 9 and up

“A detective adventure in which participants search out the Mesopotamian flood story from which the Biblical story of Noah developed.”

— Leader’s guide

— Visual resources including 93 charts/posters and photographs

— Collection of 12 stories

Above: “Focus on Noah” kit, from the curriculum library of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto. Clockwise from top left: Collection of flood stories, collection of photographs, kit box showing shipping label center bottom, leader’s guide, and collection of charts/posters

The Haunting House, Barbara Holleroth, 1974

ages 5-7

“Designed to help children, ages five through seven, be at home in the world through their experiences of building and living in houses.”

— Leader’s guide

— Visual resources including

Project Listening, Herbert Adams and William Rogers, 1974

Adults and teens

“Designed to improve interpersonal communication by providing basic training in one of the skills most necessary for meaningful communication — the skill of listening in ways most beneficial to others and to ourselves.”

— Leader’s guide

— Cassette tapes

— Book: “On Becoming a Person” by Carl Rogers

— Participant’s Material Packages, including:

class outline

listening styles inventory

booklet describing different listening styles

transcripts of some of the audio recordings

bibliography

The Way We Are: Exploring Our UU Identities: A Program in Three Parts

Part I: The Disagreements Which Unite Us, David Johnson, 1975

adults and teens

“Invites adults and/or older young people to experience, affirm, and celebrate the creative use of disagreements as one basis for our [Unitarian Universalist] unity, both in our histories and in the present….”

Part II: Our Experiencing, Believing, Celebrating

Part III: Our Ways of Relating

Africa’s Past: Impact on Our Present, Musa Eubanks, 1976

adult?

“Provides resources for an exploration of African culture during the years prior to and leading up to the time of the slave trade.”

Employing Your Total Self, Josiah Bartlett, 1976

adults

“A educational program with sessions plans and resources for creating a career/life goal workshop with two main objectives. One is to help each participant answer the question, ‘What do I do with my life?’ The other is to help participant [sic] build the self confidence to go ahead and do it.”

The Adventures of God’s Folk, Joseph Basset and Joan Hunt, 1978

ages 5-7

“Introduces children, five to seven years of age, to some of the varied realms and forms of being which fill our world. The children are introduced to the realms and forms through stories about particular human figures and their adventures in the world.”

— Leader’s guide with lesson plans

— Visual resources including photographic slides and filmstrips

— Story books

Freedom and Responsibility, Hugo Holleroth, 1983

gr. 7-9

“Designed to help junior high age young people develop a personal appreciation of the responsibilities implicit in freedom.”

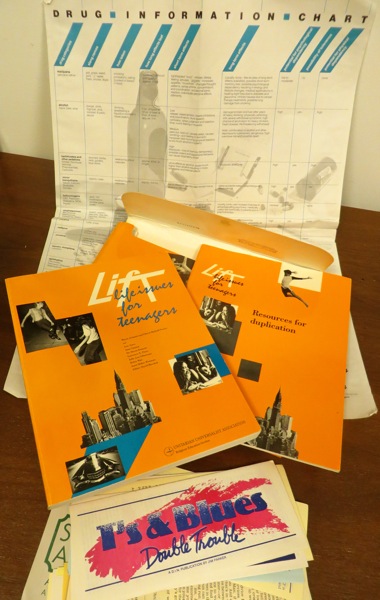

Life Issues for Teenagers, Wayne Arnason and Cheryl Markoff Powers, 1985

gr. 9-12

— Leader’s guide

— Booklet of handouts to be photocopied

— Chart of illegal drugs

— Pamphlets on legal and illegal drugs

Above photo: “Life Issues for Teenagers” kit, from the collection of Meadville/Lombard Theological School. From top to bottom: Drug information chart, kit box with Velcro closure (under books), leader’s guide (l) and booklet of reproducible handouts (r), drug information pamphlets

World Religions: A Year’s Curriculum for Junior Youth, David Marshak, ed., 1987

gr. 7-9

— Leader’s guide

— Film strip

— World map

— “One World” game

How Open the Door: Afro-American Experience in UUism, Mark Morrison-Reed, 1989

Dan, I should have posted something sooner saying how much I appreciate you blogs and how often a search I do brings me back to something you have written. So first thank you very much.

I would actually have thought to describe these programs as examples of a constructivist model of education. I would describe “Haunting House” that way as well.

But weather constructivist or as you describe them existentialist I wonder that as you survey the “suburban grey” why Spirit Play is overlooked?

Ralph, you could possibly argue that “Haunting House” had a constructivist educational philosophy. But I think of constructivism as rooted in the work of Jean Piaget, and based on notions of accommodation and assimilation. I’m not sure I see much evidence of Piagetian thinking in “Haunting House” — sure, Barbara Holleroth is aware of Piagetian developmental psychology, but I see “Haunting House” as being somewhat critical of strict constructivism, especially given that Barbara Holleroth leaves plenty of room for the divine to burst into the world of education; and apprehension of the divine is not something that is really accounted for in strict constructivism. I guess I’m also biased by conversations with one or two of the early Sunday schoolteachers of “Haunting House,” who knew Barbara Holleroth — those Sunday school teachers emphasized the existentialism, not the constructivism.

As to why I didn’t address “Spirit Play” in this post: well, this post is mostly about the multimedia era curricula; it is not really meant as a survey of all available good curricula out there.