During the Saturday afternoon breakout session of the Religious Education Association annual conference, I attended a workshop titled “Practical Neuroscience for the Pews”; it was led by Mary Cheng and Alan Weissenbacher, both doctoral candidates at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley.

Of the six people who participated in this workshop, three were full-time practitioners working in local congregations: a catechist serving a Roman Catholic parish outside Toronto, a pastor serving a Uniting Church congregation near Brisbane, Australia, and me, a minister of religious education from California. Another participant was associated with Fordham, but she also served in a local congregation, and I believe at least one other participant also served a Catholic parish. The workshop leaders encouraged full participation from the rest of us and allowed the conversation to range widely; as a result, this report may seem a little disjointed. However, the workshop seemed anything but disjointed: at the end, several of us agreed that it was by far the best presentation yet.

Goals and ends

Weissenbacher and Cheng began by asking us to consider what our goals are as religious educators, and to consider how brain science gets us to our goals. Then Weissenbacher asked a provocative question: If we use brain science to reach our religious education goals, how are we different from those who use brain science to practice mind control? Does what we are doing lay the foundation for more intrusive mind control techniques? He said that key difference is that religious educators (ethical ones, anyway) respect the agency of the people they are educating; furthermore, religious educators will be quite open about the techniques they are using.

Cheng added that it is important both to be working towards good ends, and to use good means to reach those ends. She went on to point out that there is a great deal of research being done in neuroscience these days, and much of that research if being funded by entities that may not have the highest ends in mind and may not be using neuroscience openly and transparently, e.g., companies using neuroscience to sell more products. How then can we as religious educators engage in the broader conversation about neuroscience? Further, how can we move people towards using neuroscience to good ends, and how can we shape research agendas towards those good ends?

Weissenbacher suggested that we can speak out for ethical choices as we watch neuroscience evolve. We can also advocate for ethical means and ethical ends in neuroscience research, and we can call out those that are not ethical. Elizabeth Nolan, a participant in the workshop, added that the integrative nature of the discipline of religious education allows us to ask these kinds of questions.

Kathleen Turner, another participant, pointed out that part of being an educator is “a give and take”: we share knowledge with someone else, but at the same time as educators we are also always learning from the learners. Education should only be intrusive “if it’s OK to be intrusive on both sides.” We should “stay away from power plays.”

Christine Way Skinner said that there is a lot of mystery in neuroscience for all of us (I’d add: including the scientists doing the research!). Turner said that it’s important to be able to access the original research, and to read it as best we can, so that we don’t use research that is obviously questionable or biased. Cheng reminded us again that the current research may not be entirely objective; that funding for neuroscience research goes for certain things, and not for other things.

Cheng said that she and Weissenbach had developed list of good references which they would give to those of us participating in the workshop. (This list gives bibliographic information for thirty different sources separated into the following categories: cognitive linguistics, neuroscience and education, memory and self-identity, imagination and brain change; sanctification; critical views of the reductive nature of neuroscience; habit formation; and addiction therapy and cultural change. While I don’t have permission to post this list of references on the Web, I’d be happy to mail you a photocopy if you send me a self-addressed stamped envelope.)

Connections

Weissenbach reminded us of two neuroscience truisms:

— Neurons that fire together wire together; and

— Use it or lose it.

He then posed the question: How do we replace, strengthen, inhibit, and encourage the formation of new neural pathways?

Weissenbach told a story about the youth minister who had group of students who sometimes misbehaved. When this group acted up, this youth minister made them read the Biblical book of 1 Chronicles as a punishment. Weissenbach said that while this youth minister had the best of intentions, what he was really doing was linking the reading of Scriptures with punishment in the minds of those youth; something that was certainly contrary to the ideals of his religious tradition.

“This was not a good neural pathway to establish,” Weissenbach said. We must be careful to the teaching techniques we use. Cheng reminded us of the importance of rituals around various events, and how rituals can get tied in with learning experiences. Lou Cosetino, another participant, added, Positive [neural] pathways can also be lifelong.”

Weissenbach said it’s important to be very aware of context when creating educational experiences. This prompted Nolan to reflect on the importance of visual setting and beauty in learning; both can hep people remember. Skinner added that what she learned from the Montessori technique is that teaching itself can be beautiful; we can teach beautifully.

Quoting Romans 12.2, “…be transformed by the renewal of your mind…” Weissenbach listed some of the ways that neuroscience can find practical applications in congregations and religious communities. Neuroscience can be used:

— in pastoral counseling; helping people deal with trauma, addictions, etc.;

— to help with forgiveness, where forgiveness can “rewire” neural pathways such that a person can “de-link” the anger at being hurt, recognizing that de-linking can take a fair amount of time, so forgiveness should be thought of as a process;

— to help deal with the “dark nights of the soul,” when you feel “spiritually dry”: the dark nights of the soul may actually be learning plateaus during which your neurons are catching up with what you’ve already learned, before you go on to the next spurt of growth — or to look at this slightly differently, if you have some profound spiritual experience, you’re going to need some time (probably on the order of several weeks or some months) to “consolidate” (neuronal consolidation) what you’ve experienced.

In other practical applications of neuroscience, there was some discussion of how people who go on a retreat can consolidate what they’ve learned. After a retreat or immersive experience, neuroscience would seem to indicate that it would be good to keep doing something associated with that retreat (e.g., have a daily prayer or meditation practice) to help consolidate what was learned on the retreat. Further, there was agreement that we need to recognize that the consolidation process will always be a part of the learning cycle.

Referring to immersive experiences such as retreats, Cheng said that when you have a lot of stimuli in a short time, neuroscience research indicates that this might be a good way to get the brain to initially pay attention to a new topic. But there has to be follow-up to encourage neural consolidation.

Making your unconscious work for you

“In a certain respect, we are all creators of our own unconscious,” Weissenbach said. He gave the example of learning how too drive an automobile. When first learning how to drive, you have to make a conscious effort, but over time you develop habits so that much of the process of driving becomes unconscious. A similar principle would apply with character formation: how one chooses to live one’s life will have a structural and functional effect on the brain.

Neuroscience has shown us that the unconscious is never entirely fixed, Weissenbach said. “You can form it in the way you want.” However, it is easier to form the unconscious when you are young; although neuroscience shows us that brains retain neuroplasticity into old age.

This led to a discussion among the participants and workshop leaders about the impact of violent video games on young brains. Skinner pointed out that if we could have scientific evidence that playing video games shapes the brain in negative ways, that would be a compelling argument against playing the more violent video games. The moral argument against violent video games has not been compelling for parents or kids, she said, so having scientific evidence would be useful. Weissenbach and Cheng did not know of any such evidence, although it may be out there.

Cheng said that the most damaging effect of vidoe games may actually be in the area of concentration. Neuroscience is showing us that the ability to maintain sustained attention is critical for learning. Video games may actually do damage by lowering the brain’s ability to concentrate for an extended period of time.

“If the church is going to be transformative,” Weissenbach said, “we really have to approach the whole person.” Cheng said that while we usually privilege cognition in our educational settings, neuroscience is showing us the importance of emotions. “What you remember is what is emotionally salient,” she said.

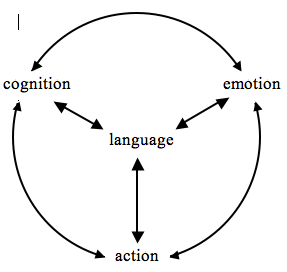

As an example, consider how religious educators can develop the virtue of hospitality. Using only cognitive approaches, e.g., presenting facts about hospitality, will not be adequate. Cheng said that neuroscience suggests that in order to teach something like hospitality, educators need to involve cognition, emotions, action, and language all together. Cheng and Weissenbach presented a diagram to help visualize how these different modalities work together:

Other topics

Cheng and Weissenbach said that engaging the imagination is very important in learning. They pointed to neuroscience research that demonstrates that just thinking about exercise can build muscle mass. Similarly, research into pianists has shown that just thinking about rehearsing a piece of music, stimulates the same areas of the brain that are activated when using one’s hands and actually playing the piano. I brought up the example of a concert pianist, Hél`ne, who has rehearsed in this way:

She also exercised her remarkable ability to prepare without actually playing. Mat Hennek, her current partner, remembers that one day, when he and Grimaud were first dating, they went shopping in Philadelphia and then to a Starbucks. At one point, he recalls, “I said to Hél`ne, ‘Hél`ne, you have a concert coming. Did you practice?’ And she said, ‘I played the piece two times in my head.'” [“Her Way: A Pianist of Strong Opinions,” by D. T. Max, 7 November 2011.]

Weissenbach said that educators have to be aware of the “culture shock dynamic.” Learning can feel disorienting in the same way that being immersed in an alien culture can be disorienting. Educators can let learners know that as the brain assimilates the new learning (neuronal consolidation), it will become easier; and it would be good for educators to remind learners of that fact.

Cheng brought up the important issue of how to provide negative feedback effectively. Negative feedback is important in learning; learners need to know when they have failed or fallen short. However, providing negative feedback can be done such that we don’t trigger the brain’s “fight or flight” mechanism.

Weissenbach talked briefly about neuroscience research that is testing a hypothesis on the power of love to transform brains. Researchers have looked at couples who are getting married, and at new parents. In both cases, the hormones that are released with new love can cause “unlearning,” allowing the brain to then learn new patterns of behavior and relating. This is obviously an evolutionary advantage: new parents and new couples need to be able to relearn how they do things.

But this has only been studied in romantic pairs and parent/child bonds. Can this kind of love also have occur in a loving religious community? Can the love of a loving community also allow for new patterns to emerge in the brain? Weissenbach suspects that a loving community may also have this effect, but the research does not yet exist to prove this.

Finally, Cheng reminded us that “neuroscience isn’t the only lens” through which to view religious education. “How do we think of a holistic way of formation, of religious education?” she said; a way that would include but not be limited to neuroscience.

Once again, you have given us an excellent summary of an interesting conference. Many thanks for posting it.

Several thoughts came to my mind while reading your most recent installment.

The first was straight from Ecclesiastes — perhaps there really is nothing new under the sun. Although neuroscience findings provide some additional insight into mechanisms (e.g., how the release of neurotransmitters changes synaptic strengths), my overall impression is that the applicable techniques that were described are primarily those learned long ago by psychologists.

And the concerns are also very similar. For example, the concerns about using the results of brain research for mind control differ little from earlier concerns about using the results of psychological research (e.g., Vance Packard’s 1957 book “The Hidden Persuaders” and his identification of the eight compelling needs that can be exploited by advertisers).

The second was that the advice to access original research to avoid results that are obviously questionable or biased seems silly to me. Even the scientists depend on more popular journalism to keep abreast of what is happening in related fields, and do not take the time to dig into the primary sources unless there is a strong need. Why should ministers read the primary sources in neuroscience, unless it is an enjoyable hobby? In my opinion, at least, the best approach is just to filter all results of new research with your common sense and judgment.

I liked the suggestions on how to make your subconscious work for you. However, I wasn’t so happy about the implied argument that because there is no scientific evidence that violent video games shape the brains in negative ways we have no grounds for objecting to them. There is ample evidence that repeated exposure to brutalizing behavior desensitizes people. We know how child soldiers are produced. It by no means follows that banning such games is the best way to deal with the problem. But, in my opinion, lack of scientific validation does not excuse failure to use judgment.

Finally, whether or not it is eventually validated by neuroscientific studies, fostering fellowship and love seems to me to be at the core of a religious community. It is what you and Rev. Amy have been doing at UUCPA, and — in my opinion, at least — it is one of the major characteristics that distinguish a church from an educational or ethical culture discussion organization. Hopefully, discoveries from neuroscience will someday allow us to do this even better.

Thanks again for all of this reporting.

A math note about that diagram: Placing “language” at the center of the drawn graph doesn’t change the fact that each of the four elements are shown acting on each other in exactly the same way. They’re just the vertices of a four-sided die, and any one of them could land point up when you throw it.

Dick — Thanks for the thoughtful comments. Some responses to your wonderful comments.

You weren’t the only one to say “nothing new under the sun.” A common refrain was, “This is what we’ve been doing as educators for years.” But it’s nice to get confirmation from neuroscience.

As for seeking out original research: most of the members of the Religious Education Association are scholars, so this comment was really aimed at the scholars in the crowd.

As far as objecting to video games: Everyone in that workshop raises objections to video games regularly. However, our objections usually go unheeded, and we are hoping that if we can present families with compelling scientific evidence that video games are harmful, our objections might get some notice.

John — You’re right. However, while I didn’t make it clear, the presenters definitely intended a two-dimensional image with language in the center (as being most important).