Stories for liberal religious kids, drawn from a wide variety of religious and spiritual traditions.

The stories on this page were originally written for a variety of purposes — worship services, classes, or just for fun. Adapt them to whatever situation you want to use them in.

Copyright: Please respect copyright. For just one example, if you use one of my copyright-protected stories in a webcast or recording, I ask that you give me credit for the story (e.g., “This story comes from Dan Harper”). You do not have to give me credit in educational settings or at home.

Cultural appropriateness: When I wrote these stories, I worked from the most culturally appropriate sources I could find, and I attempted to retain the distinctive flavor of the original religion/culture of each story. You will have to decide how you want to present other religious traditions where they conflict with Unitarian Universalist sensibilities, whether you will cover over religious differences or not. Some examples of what I mean: Will you ignore that Buddhists affirm that Buddha had 500+ previous lives? Will you adhere to Western understandings of gender, or acknowledge diverse understandings of gender? Will you acknowledge that most Christians believe Jesus is divine? Again, you will have to judge for yourself, based on the needs of your local congregation. Also note that some of these stories were written 25 or more years ago. You may want to revise older stories to match your current understandings of gender, race, cultural diversity, etc.

Table of Contents

- Daoist stories

- Confucian stories

- Other Chinese tales

- Stories from the Hebrew Bible

- Stories from the Talmud

- Stories from the Christian scriptures

- Stories from African peoples

- Jataka Tales from theBuddhist tradition

- Other Buddhist stories

- Native American stories

- Islamic stories

- Unitarian Universalist stories

- Sikh stories

- Jain stories

- Hindu stories

- Stories from ancient Greece

- Contemporary stories

DAOIST STORIES

The Bird Called P’eng

Many years ago in ancient China, the Emperor T’ang was speaking with a wise man named Ch’i.

Ch’i was telling the Emperor about the wonders of far off and distant places. Ch’i said:

“If you go far, far to the north, beyond the middle kingdom of China, beyond the lands where our laughing black-haired people live, you will come to the lands where the snow lies on the ground for nine months a year, and where the people speak a barbaric language and eat strange foods.

“And if you travel even farther to the north, you will come to a land where the snow and ice never melts, not even in the summer. In that land, night never comes in the summer time, but in the winter, the sun never appears and the night lasts fro months at a time.

“And if you go still farther to the north, beyond the barren land of ice and snow, you will come to a vast, dark sea. This sea is called the Lake of Heaven. Many marvelous things live in the Lake of Heaven. They say there is a fish called K’un. The fish K’un is thousands of miles wide, and who knows how many miles long.”

“A fish that is thousands of miles long?” said the Emperor. “How amazing!”

“It is even more amazing than it seems at first,” said Ch’i. “For this giant fish can change shape and become a bird called P’eng. This bird is enormous. When it spreads its wings, it is as if clouds cover the sky. Its back is like a huge mountain. When it flaps its wings, typhoons spread out across the vast face of the Lake of Heaven for thousands of miles. The wind from P’eng’s wings lasts for six months. P’eng rises up off the surface of the water, sweeping up into the blue sky. The giant bird wonders, ‘Is blue the real color of the sky, or is the sky blue because it goes on forever?’ And when P’eng looks down, all it sees is blue sky below, with the wind piled beneath him.”

A little gray dove and a little insect, a cicada, sat on the tree and listened to Ch’i tell the Emperor about the bird P’eng. They looked at each other and laughed quietly. The cicada said quietly to the dove, “If we’re lucky, sometimes we can fly up to the top of that tall tree over there. But lots of times, we don’t even make it that high up.”

“Yes,” said the little dove. “If we can’t even make it to the top of the tree, how on earth can that bird P’eng fly that high up in the sky? No one can fly that high.”

Ch’i continued to describe the giant bird P’eng to the Emperor. “Flapping its wings, the bird wheels in flight,” said Ch’i, “and it turns south, flying across the thousands of miles of the vastness of the Lake of Heaven, across the oceans of the Middle Kingdom, heading many thousands of miles towards the great Darkness of the South.”

A quail sat quietly in a bush beside the Emperor and Ch’i. “The bird P’eng can fly all those thousands of miles from the Lake of Heaven in the north across the Middle Kingdom, and into the vast ocean in the south?” said the quail to himself. “Well, I burst up out of the bushes into flight, fly a dozen yards, and settle back down into the bushes again. That’s the best kind of flying. Who cares if some big bird flies ninety thousand miles?”

The Emperor listened to Ch’i, and said, “Do up and down ever have an end? Do the four directions ever come to an end?”

“Up and down never come to an end,” said Ch’i. “The four directions never come to an end.

“That is the difference between a small understanding and a great understanding,” continued Ch’i. “If you have a small understanding, you might think the top of that tree is as high up as you can go. If you have a small understanding, you might think that flying to that bush over there is as far as you can go in that direction. But even beyond the point where up and down and the four directions are without end, there is no end.”

But the quail did not hear, for she had flown a dozen yards away in the bushes. The cicada did not hear because it was trying to fly to the top of a tree. And the little dove did not hear because he, too, was flying to the top of the nearby elm tree.

Source: From the Chuang-tzu [Zhuangzi], chapter 1, translations by Lin Yutang, Burton Watson, and James Legge. The closing paragraph is my adaptation of a line that may not have been part of the original text.

Frog in a Well

Once upon a time, Kung-sun Lung was talking to Prince Mou of Wei.

Kung-sun Lung said, “When I was just a boy, I learned all the teachings of the great kings of old, and I learned how to be good, kind, and righteous. I studied the wisdom of ancient philosophers; I learned all the arguments about being and the attributes of being; I learned what was true and correct, and what was false and incorrect. I thought I understood every subject under the sun.

“But when I heard the teachings of Chuang-tzu,” said Kung-sun Lung, “I get all confused. Maybe I’m not as good at arguing as he is. Or maybe I don’t know as much as he does. But now that I have heard the teachings of Chuang-tzu, I feel like I don’t even dare open my mouth. What is wrong?”

Prince Mou leaned forward on his stool. He drew a long breath, looked up to heaven, and smiled. “Have you ever heard the story of the frog of the broken-down well?” he said.

Kung-sun Lung shook his head.

“Well, then,” said Prince Mou, “Let me tell you the story.”

***

Once upon a time, there was a frog that lived in a broken-down well. Ordinarily, this frog would not want to live in a well, because once he got into the well, he wouldn’t be able to get out again. But the broken-down sides of the well allowed the frog to climb in and out of the well as if he were climbing a ladder, or a broken-down staircase.

One day, the frog climbed out of the well, and as he walked around, he happened to fall into a conversation with the Turtle of the Eastern Sea. She asked the frog how he enjoyed living where he did.

The little frog said he enjoyed it very much. “I hop onto the edge of my broken-down well,” said the frog, “and from there I climb down into the water, using the broken-down sides of the well as a grand staircase to the water. When I get close to the water, I dive into it. I draw my legs together, and keep my chin up, and swim around the well. I dive down to the bottom of the well, down and down until my feet are lost in the mud. I come back up for air, and I look around at everyone else who lives in the well — the little crabs, the insects, the tadpoles — and I see that there is no one who match me. I am in complete command of the water of my whole little valley. It is the greatest pleasure to enjoy myself in my broken-down well. You should come with me and try it yourself.”

With that, the little frog led the way to his broken-down well. The Turtle of the Eastern Sea tried to follow him. But her front right foot got stuck in the well, before she had even manage to move her front left foot forward. At this, she drew back, saying that it would be better if she didn’t try to get into the well.

Instead, the Turtle of the Eastern Sea tried to tell the little frog he she enjoyed living where she did.

“The Eastern Sea where I live,” said the turtle, “is thousands of miles across, so far I can’t even measure it. It is more than a mile deep, so deep that I cannot find the bottom. If your valley got flooded, and hundreds more valleys like yours also got flooded, and if they all drained into the Eastern Sea, it is so huge that the level of the sea would not rise. If there were to be a drought, so that no rain fell for seven out of eight years, it is so huge that the level of the sea would not fall. The waters of the Eastern Sea do not rise or fall for any cause, great or small. And this is the greatest pleasure of living in the Eastern Sea.”

When the little frog from the broken-down well heard the turtle describe how big the Eastern Sea was, he was amazed and frightened. His mouth opened, and he was lost in surprise.

***

When Prince Mou finished telling this story, he said to Kung Sung-lung, “Do you understand how this story answers your question? Someone who isn’t yet able to understand the true difference between truth and falsehood can’t possibly understand Chuang-tzu. It would be like asking a mosquito to carry a mountain on its back.

“Chuang-tzu is like like the Turtle of the Eastern Sea, able to reach the deepest depths of the earth, and able to rise to the highest heights of sky. With freedom he launches out in any direction, and starting from what is confusing, he always comes back to what is understandable. Yet you think you are going to understand what he’s talking about by making lots of arguments! It is if you are trying to look at the whole sky through a small tube. You are like a frog in a broken-down well.”

Upon hearing this, Kung-sun Lung’s mouth fell open in surprise. He felt like his tongue was stuck to the roof of his mouth. He slunk away, and when he was out of sight of Prince Mou, he ran away home.

Source: “Frog in a Well”: from the Chaung-tzu [Zhuangzi], 17.10, adapted from the James Legge translation.

The Useless Tree

A certain carpenter named Zhih was traveling to the Province of Ch’i. On reaching Shady Circle, he saw a sacred tree in the Temple of the Earth God. It was so large that its shade could cover a herd of several thousand cattle. It was a hundred yards thick at the trunk, and its trunk went up eighty feet in the air before the first branch came out.

The carpenter’s apprentice looked longingly at the tree. What a huge tree! What an enormous amount of timber could be cut out of it! Why, there would be enough timber in that one tree to make a dozen good-sized boats, or three entire houses.

Crowds stood around the tree, gazing at it in awe, but the carpenter didn’t even bother to turn his head, and kept walking. The apprentice, however, stopped to take a good look, and then had to run to catch up with his master.

“Master, ever since I have handled an adze in your service,” said the apprentice, “I have never seen such a splendid piece of timber. How was it that you did not care to stop and look at it?”

“That tree?” said the Master, “It’s not worth talking about. It’s good for nothing. If you cut down that tree and made the wood it into a boat, it would sink. If you took the wood to build a house, the house would break apart and rot. See how crooked its branches are! and see how loose and twisted is its grain! This is wood that has no use at all. Not only that, if you try to taste one of its leaves, it is so bitter that it would have taken the skin off your lips, and the odor of its fruit is enough to make you sick for an hour. It is completely useless, and because it is so useless, the tree has attained a huge size and become very old.”

The carpenter told his apprentice to dismiss the tree from his thoughts, and they continued on their way. They arrived home late at night, and both of them went straight to bed.

***

While the carpenter was asleep, the spirit of the tree came and spoke to him.

“What did you mean when you spoke to your apprentice about me?” said the spirit of the tree. “Of course I am not like the fine-grained wood that you carpenters like best. You carpenters especially like the wood from fruit trees and nut trees — cherry, pear-wood, and walnut.

“But think what happens! As soon as the fruits or nuts of these trees have ripened, you humans treat the trees badly, stripping them of their fruits or nuts. You break their branches, twist and break their twigs. And then you humans cut down the trees in their prime so you can turn them into boards and make them into furniture.

“Those trees destroy themselves by bearing fruits and nuts, and producing beautiful wood,” said the spirit of the tree. “I, on the other hand, do not care if I am beautiful. I only care about being useless.

“Years ago, before I learned how to be useless, I was in constant danger of being cut down. Think! If I had been useful, your great-grandfather, who was also a carpenter, would have cut me down. But because I learned how to be useless, I have grown to a great size and attained a great age.

“Do not criticize me, and I shan’t criticize you,” the spirit of the tree said. “After all, a good-for-nothing fellow like yourself, who will die much sooner than I will — do you have any right to talk about a good-for-nothing tree?”

***

The next morning, the carpenter told his dream to his apprentice.

The apprentice asked, “But if the goal of the tree is to be useless, how did it become sacred tree living in the Temple to the Earth God?”

“Hush!” said the master carpenter. “You don’t know what you’re talking about. And I should never have criticized the tree. The tree is a different kind of being than you and I, and we must judge it by different standards. That’s why it took refuge in the Temple — to escape the abuse of people who didn’t appreciate it.

“A spiritual person should follow the tree’s example, and learn how to be useless.”

Source: from Chuang-tzu [Zhuangzi] 1.16, based on translations by Lin Yutang, Burton Watson, and James Legge.

The Yellow Emperor

Thousands of years ago, Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, reigned in the land of Qi. This is one of the many stories told about this emperor:

For the first fifteen years of his reign, Huangdi took great pleasure in his position. He rejoiced that all the people in the Empire looked up to him as their emperor. He took care of his body. He ate well, and took the time to enjoy beautiful sights and sounds. Yet inside he was sad and disturbed, while his face looked haggard and ill.

Huangdi decided to change. He saw that the Empire faced great trouble and disorder. For the next fifteen years of his reign, he worked night and day to rule the people with wisdom and intelligence. Yet inside he was sad and disturbed, while his face looked haggard and ill.

Huangdi sighed heavily. “I was miserable in the first fifteen years of my reign, when I devoted all my attention to myself and my own needs, and paid no attention to the Empire. I was miserable in the second fifteen years of my reign when I devoted all of my time and energy to solving the problems of the Empire and paid no attention to myself. I see now that all my efforts have not succeeded in establishing good government, nor in making myself happy.”

He left the palace and dismissed all his servants. He went to live in a small building beside of the palace. He sat by himself for three months purifying his mind.

One day while napping, he dreamt that he traveled to the kingdom of Huaxu. This utopia could not be reached by ship, or by any vehicle, or even traveling by foot. It could only be reached through spiritual travel.

The people who lived in this kingdom did not feel joy in living, nor did they fear dying, so they never died before their time. They were not attached to themselves, so they felt neither love nor hatred. Profit and loss did not exist in their country. Thunder did not deafen them, physical beauty did not affect them, steep mountains and deep valleys could not slow them down. And Huangdi saw there was no ruler in this mystical kingdom: everything simply went on of its own accord.

Huangdi awoke from the dream. He called for his three advisors and told them what he had seen. “I thought it was impossible to rule others fairly and wisely. Then I fell into a deep sleep and dreamed this dream. Now I know the Perfect Way cannot be found through the senses. But I cannot tell you about the Perfect Way, because you cannot use your senses to learn it.”

That was all the Yellow Emperor said. The rest of his life, he ruled Qi the way the mystical kingdom was ruled: let everything simply go on of its own accord. Everything in the country of Qi was calm and orderly. When Huangdi died, the people mourned his death two hundred years.

Notes: Huangdi = 黄帝 — Huaxu = 華胥國

Sources: Daoist teachings translated from the Book of Lieh-Tzü [Liehzi], Book II “The Yellow Emperor,” trans. Lionel Giles, 1912. Supporting source: Alchemists, Mediums, and Magicians: Stories of Taoist Mystics, trans. and ed. Thomas Cleary, p. 8 n. 29. N.B.: This could be a troubling story for some religious liberals. The notion that the best leaders are those who do no work will be anathema to religious liberals who have come out of Protestantism, and who, while they might have become post-Christian in theology, have not abandoned the Protestant work ethic. Yet a documentary approach to telling religious stories should not soften the essential foreignness of other religions, when such foreignness is present.

Planting a Pear Tree

One day in the marketplace, a farmer was selling pears he had grown. These pears were unusually sweet, so the farmer asked a high price for them. A Daoist priest stopped at the barrow in which the farmer had displayed these lovely pears.

“May I have one of your pears?” he said.

The farmer said, “Move aside, so paying customers can buy my pears.” The farmer knew the priest expected a pear for free. When the priest did not move, the farmer began to curse and swear at him.

The priest said, “You have several hundred pears on your barrow. I ask for a single pear. Why get angry?”

Some people nearby told the farmer to give the priest a pear that was bruised, which he couldn’t sell anyway. But the farmer was stubborn, and refused. The constable of the town came over to see what was going on. Seeing that things were getting out of hand, he bought a pear and gave it to the Daoist priest.

The priest bowed to the constable, and thanked him. Then the priest turned to the townspeople and said, “We Daoist priests give up all money and possessions. When we see selfish behavior, it’s hard for us to understand it. I have some pears with a very fine flavor, and unselfishly I would like to share them with you.”

Someone in the crowd called out, “If you have pears of your own, why did you want one of the farmer’s pears?”

“Because,” said the priest, “I needed a seed to grow my pears from.” He ate up the pear that the constable had given him. He took a seed, unstrapped a pick from his back, and made a hole in the ground. He dropped the seed in the hole and covered it with earth. Then he said, “Could someone bring me a little hot water, please, with which to water the seed?”

Someone ran into a neighboring shop and brought some steaming water. The priest poured the water over the seed. Everyone watched closely, for though it seemed like a joke, Daoist priests were supposed to have knowledge of mystical arts.

Suddenly green sprouts began shooting out of the ground. They grew until they became a pear tree. The tree sprouted green leaves, and put forth white flowers. Bees buzzed among the flowers, the petals dropped, and soon tiny green fruits grew and ripened into fine, large, sweet-smelling pears on every branch.

The priest picked the pears and gave one to everyone in the crowd. Then the priest turned and hacked at the tree with his pick until he cut it down. Picking up the tree and throwing it over his shoulder, leaves and all, he walked quietly away.

The farmer had been standing in the crowd the whole time, forgetting all about his own business. When the priest walked away, he turned back to his barrow and discovered that every one of his pears was gone. He then knew that the pears that old fellow had been giving away were really his own pears. And when the farmer looked more closely at his barrow, he saw that one of its handles had been newly cut off.

Boiling with anger, the countryman set off after the Daoist priest. But as he turned the corner where the priest had disappeared, there was the lost wheel-barrow handle lying next to a wall. It was, in fact, the very pear tree that the priest had cut down.

But there was no trace of the priest. The townspeople watched the farmer’s anger as they finished eating their sweet, juicy pears.

Source: Pu Songling, trans. Herbert A. Giles, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (London: Thomas De La Rue & Co., 1880).

CONFUCIAN STORIES

Miracles at the Birth of Kongzi [Confucius]

Once upon a time, in a place called Tsou, there lived a man named Shuliang He. He had been a soldier, now retired, and he was so tall that people said he was ten feet tall. He lived in China some two thousand five hundred years ago, at about the time when Gautama Buddha lived in India.

Shuliang He was an older man, perhaps 70 years old. He had had nine daughters with his first wife. But Shuliang He also hoped to have a son. So he went to the head of the noble house of Yen, and asked for one of their daughters in marriage. The youngest daughter, Yan Zhengzai, said that she would be willing to marry this older man.

The two were married, and not long thereafter Yan Zhengzai traveled to Mount Ni in Shangdong Province, one of the mountains that Emperor Shun had dedicated to the worship of its guardian spirit. Knowing that her husband would like to have a son in addition to his nine daughters, she offered up a prayer to give birth to a son. That night, she dreamed that a spirit came to her and said, “You shall have a son, who will be a great sage and prophet, and you must bring him forth in the hollow mulberry tree.” Not long after this dream, she became pregnant. (1)

Some people say that while Yan Zhengzai was pregnant, she fell into a dreamy state, and five old men came up to here, leading behind them a unicorn (this was a Chinese unicorn, or qilin, was the size of a small cow, had one horn, and was covered in scales). The unicorn carried in its mouth a tablet made of green jade. On the tablet was carved a prophecy: “The son of the essence of water shall soon succeed to the withering Zhou, and be a throneless king”; which meant that her baby would grow up to become wise and valued leader, even though he would never hold political power. She tied a silk scarf around the qilin’s horn, upon which the animal disappeared. (2)

Soon it came time for Yan Zhengzai to give birth. She told her husband that she must give birth in the “hollow mulberry tree,” wherever that was, and her husband said that there was a dry cave in a hill nearby that went by that name. So even though she was near to giving birth, they travelled to the dry cave that was named “The Hollow Mulberry.” (3)

On the night the child was born, two dragons appeared in the sky to keep watch; one to the right of the hill where the cave was, the other to the left of the hill. Then two spirits appeared in the air above the hill, two women who poured out fragrant drafts, as if to bathe Yan Zhengzai in beautiful aromas as she was giving birth. (4)

And within the cave, Yan Zhengzai heard music, and a voice saying to her: “Heaven is moved at the birth of your son, and sends down harmonious sounds.” A spring of water bubbled up within the dry cave, so that Yan Zhengzai could bathe her new baby; and to confirm the prophecy that the new baby was the “son of the essence of water.” (5)

Five venerable men came from afar to pay their respects to the new baby. (6) Some people said they were the five old men of the sky, the five immortals who never die, and they had come down from the five planets to celebrate the birth of this great child. His parents named him King Qiu.

This little baby grew up to be a great human being, a prophet and sage who became known as Kongzi, the Master or Teacher Kong. (In the Western world, he is best known by the name Confucius.)

Kongzi said that by the age of fifteen, he knew that he wanted to spend the rest of his life learning how to master one’s own self, and learning how we can live harmoniously with brothers and sisters, with our parents and children, with all those with whom we come into contact. He learned these things, and he began to teach others how to live wisely and well. Today, some two thousand five hundred years after he was born, millions of people around the world continues to find wisdom in his teachings.

Sources:

(1) Confucius, the Great Teacher: A Study, by George Gardiner Alexander. pp. 33 ff. The Chinese Classics: Life and Teachings of Confucius, vol. 2, trans. James Legge, p. 58. Confucius: His Life and Thought, by Shigeki Kaizuka (Dover reprint, 1956/2002), pp. 42-44.

(2) Sages and Filial Sons: Mythology and Archaeology in Ancient China, by Julia Ching and R. W. L. Guisso (Chinese University Press, 1991), p. 143. Legge, p. 58 n.

(3) Legge, p. 58 n.

(4) Ibid.

(5) The Dragon, Image, and Demon: The Three Religions of China: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, by Hampden C. DuBose (New York: A.C. Armstrong, 1887), pp. 91-92.

(6) Ibid.

OTHER CHINESE TALES

Pangu and the beginning of the universe

At the beginning, there was little difference between heaven and earth. All was chaos, and heaven and earth had no distinct forms, like the inside of a chicken’s egg. Within this chaos, the god Pangu was born inside the egg.

Pangu grew and grew inside the egg. After 18,000 years, the egg somehow opened up. Some say that Pangu stretched himself inside the egg, and shattered the egg’s shell into pieces.

Once the egg had shattered open, the lightest part of it, the part that was like the white of a chicken’s egg, rose upwards, and became the heavens. The heavier part of the egg, like the yolk of a chicken’s egg, sank downwards and became the earth. Pangu took a hammer and an adze, and cut the connections between earth and the heavens. Then to keep earth and the heavens from merging together once again, Pangu stood between them, serving as the pillar that kept them apart.

Pangu lived within earth and the heavens, standing between them. And one day he began to transform. He became more sacred than the earth, and he became more divine than the heavens. The heavens began to rise, going up one zhang, or about ten feet, each day. The earth began to grow thicker, thickening by one zhang each day. And as the heavens rose, so too Pangu grew; he grew one zhang taller each day. And this continued for 18,000 years: each day, the earth grew thicker, and the heavens rose higher, and Pangu grew taller.

At the end of 18,000 years, the heavens had grown very high, the earth had grown very thick, and Pangu had grown into a giant. He was now 90,000 li (or 87,000 miles) tall, the distance between earth and the heavens. Finally, all had become stable. The heavens had stopped rising. The earth had stopped growing thicker.

Not everyone agrees what Pangu looked like. Some say he had a dragons’ head and the body of a serpent. But most say he looked like human beings, except that he was a giant, and he had a horn on his head.

After uncounted years, Pangu felt that he was dying. As he was dying, his body began to transform itself.

His left eye became the sun, his right eye became the moon, and his hair and beard became the sky and the stars. His breath became the winds and clouds, and his voice became the thunder. His arms and legs became the four extremes or borderlines of the earth, and his head and torso became the Five Mountains. His blood became the rivers, his teeth and bones became the rocks and minerals, and his flesh became the fields and the soil. His skin became plants, and his sweat became the rain and the dew.

So it was that when he died, the body of Pangu became the whole universe and everything in it.

Source: The first part of the story is from the Sanwu Liji; and the second part of the story is from the Wuyun Linianji. Translation and retelling from Handbook of Chinese Mythology, Lihui Yang and Deming An (Oxford University, 2005), pp. 64-66, 170-176; with reference to Classical Chinese Myths, Jan Walls and Yvonne Walls (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1984); and Chinese Myths and Legends, Lianshan Chen (Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 6-7. See also Asian Mythologies, ed. Yves Bonnefoy (University of Chicago, 1993), pp. 234 ff.

The Land of the Great

In the year 684, the scholar T’ang Ao and his friend Lin Chih-yang grew disgusted with the behavior of Empress Wu, ruler of their home land of China. These two friends thought the empress was both foolish and aggressive, and they also felt that under her reign anything might be bought or sold, including a person’s honor.

They decided they would travel the world and see how other nations were ruled, and so they found a guide, a man named Toh Chiu-kung who seemed to know everything and to have traveled everywhere, and then they got on board a ship and sailed over the sea.

After visiting several nations, they came at last to the Land of Great People. In fact, they almost passed by this small nation except that T’ang had heard that in the Land of the Great, no one walked but instead everyone had their own personal cloud which carried them where they wanted to go. Toh warned that they would have to leave the ship and walk a long way inland to really see this country. But T’ang must go see the Land of the Great, so they began to walk inland over some steep hills.

Soon they became lost in a maze of trails, and did not know which way to turn. They were very glad when at last they saw a small temple hidden in among bamboos. Out of the temple came an old man who looked perfectly ordinary except for two things. First, he was riding on a cloud. Second, while in their country anyone who lived in a temple would have to be a priest who shaved their head, did not eat meat, did not drink wine, and was not married — well, this old man had long hair, carried a glass of wine in one hand, a plate of meat in the other hand, and through the door they could see his wife seated at a table.

It is hard to say which shocked the two friends more — a man floating upon a cloud, or a long-haired, meat-eating, wine-drinking, married priest! However, they remained polite. The old man smiled at them, put down his wine and meat, and invited them into the temple. T’ang, speaking for his friends, bowed low and asked what the name of the temple. The old man replied that it was the temple of the goddess of mercy, and that he was the priest of the goddess.

Upon hearing this, Lin asked, “But, respected sir, how can it be that you are a priest but do not shave your head?” Lin decided not to ask about the wine or the meat, or the man’s wife.

“My wife and I have lived here and been the priests ever since we were young,” said the old man. “Every day, we burn incense and candles before the shrine. Here in our country, when we heard that China had accepted the Law of the Buddha, and that priests with shaved heads had become common there, we too decided to accept the Law of the Buddha, but we decided to do away with the usual promises of a priest. Thus we can grow our hair, get married, eat meat, and drink wine.”

When the old man learned that his visitors were from China, he urged them to stay with him. But no, they said they must go on to see the chief city of the Land of the Great.

“But could you please answer one question,” said T’ang. “Could you please explain the reason why the people of your country all have clouds underneath their feet? Is this something that you are born with?”

“Yes, we are born with these clouds,” said the old man. “The clouds come in various colors, and colors change depending on the character of each person. The best clouds have stripes like a rainbow. The second-best clouds are yellow in color. The worst clouds have no color at all, and look dark, as if there is nothingness, or a hole, underneath the person’s feet.”

T’ang asked the old man to show them the way to the city so they could see more of these clouds, and the old man explained which trail to follow.

Soon they were in the great city. There were throngs of people in the city streets, each moving around on a small cloud. They saw clouds of many different colors: red, yellow, orange, green, and so on.

At last they saw a homeless man, who obviously hadn’t taken a bath in weeks, whose cloud looked like a brilliant rainbow.

“Why, the priest told us that a rainbow cloud was best of all,” said T’ang, “and here we see a filthy, dirty homeless person with a rainbow cloud!”

“You may remember,” said Lin, “that that priest had a rainbow cloud himself. Yet how could a wine-drinking, meat-eating, long-haired, married priest be considered to be a good person? Just so, how could a homeless person be considered to be a good person? There is something here I do not understand.”

“As you know,” said Toh, their guide, “I have been to this country before. What I learned then was that good and virtuous people have clouds of the best colors, no matter what other people may think. A priest who does not follow all the rules may have a good cloud, if they are a good person. A homeless person may have a good cloud, if they are a good person. The only way to change the color of your cloud to a better color is to become a better person.

“Because of this fact,” continued Toh, “there are poor people who ride on rainbow clouds, as we have just seen, and there are rich and powerful people whose ride on clouds that lack all color at all, and look like holes of darkness. Of course, everyone avoids the people who have a cloud of darkness. On the other hand, the people of this country get the greatest pleasure from seeing acts of kindness, and everyone is always trying to become a better person.”

“Is this why this is called the Land of the Great?” asked T’ang.

“Yes,” said Toh. “It is called the Land of the Great, not because because people are big and tall, and not because they are rich and powerful. This is called the Land of the Great because here everyone is trying to become a better person.”

Suddenly they noticed that the people around them were pushing back to the sides of the street, leaving the center of the street to a person of great wealth and power, who looked almost exactly like a wealthy powerful person in their own land, with a red umbrella over his head, with assistants in front and behind carrying official documents and beating gongs, and so on. The difference was that this wealthy person was riding on a cloud that was carefully and completely covered by a red silk cloth.

“Obviously,” said T’ang, “in this country, the wealthy and powerful do not need to ride on horses, for they can move about on these convenient clouds. But one thing I do not understand — why is this man’s cloud mysteriously covered by a red silk cloth?”

“The fact is,” said Toh, lowering his voice so he could not be heard except by the two friends, “this man, like too many other people with lots of money and a high social position, has a cloud of a bad color. His cloud is not exactly one of those horrible clouds of dark nothingness. But his cloud is the color of charcoal and ashes. This means he is not completely bad, but it does mean — as we like to say — that his hands are not so clean as they ought to be.”

“In other words,” said Lin, “he is not exactly a wicked person, but he most certainly is not a good person.”

“That is a good way of putting it,” said Toh. “His cloud takes on the color of his inmost mind. He is not a good man, and so his cloud a bad color. He tries to cover up his bad-colored cloud with red silk, but red silk does not change the color of his cloud. Nothing will change the color of his cloud until his heart becomes good again, until all his actions are once again good. But still, he covers his cloud with red silk, because at least that way no one is quite sure just how bad he really is.”

“How unjust this is!” cried Lin.

“But why do you think this is unjust?” asked T’ang.

“It is unjust that these clouds exist only here, in the Land of the Great,” said Lin. “It would be very useful if we had these clouds in our own nation, for if every wicked person rode about upon a marker of their wickedness, why, that would make good people’s lives easier.”

“My dear friend,” said Toh, “though wicked people in our nation do not ride about on colored clouds, nevertheless you can tell from a person’s looks what the color of their heart is. Someone with a bright, shining look in their eyes surely must have a rainbow-colored heart. And we all know people who have a blankness in their looks that shows an emptiness in their hearts.”

“That may be so,” answered Lin, “but I for one have been fooled by a person’s looks. I would rather we could see the color of the cloud they ride about on.”

Source: Visits to Strange Nations [Ching Hua Yüan], an anonymous Chinese work of the 17th century, from Gems of Chinese Literature, 2nd ed., trans. Herbert A Giles (Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh, 1923).

STORIES FROM THE HEBREW BIBLE

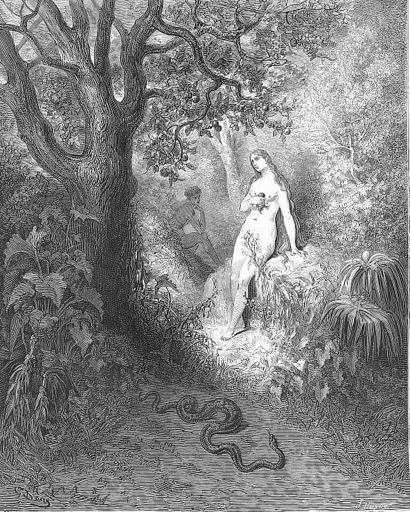

The Garden of Eden

These are the beginnings of the heavens and the earth, when they were created.

In the day that Yahweh made the earth and the heavens, when no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up — for Yahweh had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no one to till the ground; but a stream would rise from the earth, and water the whole face of the ground — then Yahweh formed a man (in Hebrew, “formed a man” is said adam), from the dust of the ground (which in Hebrew is said adamah). Yahweh breathed into the man’s nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.

And Yahweh planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed. Out of the ground Yahweh made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food, the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

A river flows out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it divides and becomes four branches. The name of the first is Pishon; it is the one that flows around the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold; and the gold of that land is good; and there are precious stones there. The name of the second river is Gihon; it is the one that flows around the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is Tigris, which flows east of Assyria. And the fourth river is the Euphrates.

Yahweh took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it (the name “Eden” means “pleasure and delight”). And Yahweh commanded the man, “You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die.”

Then Yahweh said, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner.” So out of the ground Yahweh formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name. The man gave names to all cattle, and to the birds of the air, and to every animal of the field; but for the man there was not a helper to be his partner.

So Yahweh caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and he slept. Then Yahweh took one of the man’s ribs out, and closed up its place with flesh. Yahweh made the rib that had been taken from the man into a female human being, a woman, and brought her to the man.

The man said, “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; this one shall be called Woman (which in Hebrew is said ishshah), for out of a man (which is Hebrew is said ish) this one was taken.”

Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh. And the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed.

Now the serpent was more crafty than any other wild animal that Yahweh had made. He said to the woman, “Did Yahweh say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden’?”

The woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; but Yahweh said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die.’”

But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die; for Yahweh knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like Yahweh, knowing good and evil.”

So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.

They heard the sound of Yahweh walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of Yahweh among the trees of the garden.

But Yahweh called to the man, and said to him, “Where are you?”

The man said, “I heard the sound of you in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself.”

Yahweh said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?”

The man said, “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit from the tree, and I ate.”

Then Yahweh said to the woman, “What is this that you have done?”

The woman said, “The serpent tricked me, and I ate.”

Yahweh said to the serpent, “Because you have done this, cursed are you among all animals and among all wild creatures; upon your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel.”

To the woman, Yahweh said, “I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.”

And to the man, Yahweh said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife, and have eaten of the tree about which I commanded you, ‘You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

The man named his wife Eve, because she was the mother of all living (in Hebrew, “Eve” resembles the word for living). And Yahweh made garments of skins for the man and for his wife, and clothed them.

Then Yahweh said, “See, the man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil; and now, he might reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life, and eat, and live forever.”

Therefore Yahweh sent the man forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man; and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim, who were angelic guardians of fearsome appearance, wielding swords that flamed and turned to guard the way to the tree of life.

Source: Hebrew Bible, Genesis 2.4-3.24. With reference to the feminist interpretation of Rev. Ellen Spero.

David and Goliath

Once upon a time there was a shepherd named David. His three older brothers went off to fight in the army of Israel, under the command of King Saul. But David stayed behind with their father, Jesse, in the town of Bethlehem.

One day after his brothers had been gone for forty days, David’s father said to him, “Go take this bread and cheese and corn to the camp where your brothers and the rest of the army are, and give all this to the captain of their company.”

When David got to the place where the army of Israel was, they were just getting ready to go to battle with the army of the Philistines.

A champion came out of the camp of the Philistine army, a man named Goliath. He was over nine feet tall. He had a helmet of brass on his head, and he was armed with a coat of mail, and he wore brass armor on his legs, and brass armor on his back. He carried a long spear, with an iron tip that weighed six hundred shekels.

He stood in the valley between the two armies, and called out to army of Israel. “Why are ye come to set your battle in array?” he shouted. “Am not I a Philistine, and ye servants of Saul? Choose a man from among you, and let him come down to me. If he be able to fight with me, and to kill me, then we will be your servants. But if I prevail against him, and kill him, then you shall all be our servants, and serve us.”

When Saul and the army of Israel heard Goliath’s challenge, they were greatly afraid.

David came up to the army of Israel right after Goliath has issued his challenge. All the men in the army were talking about it. “Have you seen this man who has come up from the army of the Philistines?” they said. “King Saul has promised that if any man dares to take Goliath’s challenge, and also manages to kill Goliath, the king will give that man great riches, and give him the princess in marriage.”

Eliab, David’s eldest brother, saw David just then. “What are you doing here?” said his brother angrily. “I know your pride, and the naughtiness of your heart. You just came down so that you could watch the battle.”

David told Eliab that their father had sent him. “And now that I’m here,” he said, “I will go and fight this Goliath.”

Saul heard that David said he would fight Goliath. So Saul sent for David. But when he saw how young David was, he said, “You are not able to fight Goliath.”

“I have watched my father’s sheep,” said David, “and when a lion and a bear came and took a lamb from the flock, I went after them. I took the lion by his beard and killed him; and I killed the bear; and I can kill this Goliath too.”

Saul gave David a helmet made of brass, and a sword to buckle around his waist. But David took off the helmet and the sword. He took his shepherd’s staff, and he took five smooth stones from the brook, and he took his sling.

When Goliath, the Philistine, saw David, the shepherd, he laughed. “Come to me,” said Goliath, “and I will give leave you dead for the vultures to feed upon.”

“You come with a sword and a shield,” said David. “But I come in the name of Adonai, the god of Israel. Adonai will deliver you into my hand, and I will leave you dead for the vultures to feed upon.”

Goliath arose and started walking forward to meet David. David put his hand in his bag and took one of the five smooth stones. He ran ahead to meet Goliath, put the stone in his sling, and using his sling hit Goliath right in the forehead, and Goliath fell down dead.

When David returned, he was taken to Saul, and Saul adopted him as one of his own sons. And David became best friends with Saul’s own son, Jonathan.

Source: Hebrew Bible, 1 Samuel 18.

Saul and David

Once upon a time there lived a good and holy man named Samuel. Samuel lived in the land of Israel, and he knew that Israel needed a good and strong leader. Samuel decided that Saul, son of Kish, would be the best person to rule over Israel, and so he anointed Saul king, and then served Saul as a holy man and an advisor.

Saul was a handsome man. There was not a man among all the people of Israel who was as handsome as he, and he was so tall that he stood head and shoulders over everyone else.

Saul was a likeable man. When he was a boy, he was easy-going and treated his parents with respect. When he became a man, he remained easy-going and friendly.

But even though he was handsome and likeable, every once in a while Saul would fall into a dark mood; more than just a bad mood, when Saul fell into one of these dark moods, the light went out of hid eyes. When he was in one of his dark moods, he didn’t want to talk with anyone, he just wanted to stay by himself in his throne room. When he was in one of his dark moods, sometimes he would do things that were dangerous or foolish.

One day Samuel sent Saul off to do battle with the evil tribe of the Amakelites. Samuel warned Saul that if he won the battle, he must slaughter all the Amakelites’ cattle. For their cattle was diseased, and if Saul brought the diseased cattle back to Israel, all the cattle of Israel would grow sick and soon die.

Saul fought the battle, and he won. But alas, after the battle he fell into one of his dark moods. He forgot what Samuel had told him, and he brought all the diseased cattle back to Israel.

Samuel met him, and cried out, “What is all this lowing of cattle that I hear?”

Suddenly Saul remembered what Samuel had him — but it was too late. Saul worried that Samuel could no longer trust him, and his mood grew even darker.

Samuel saw that Saul kept falling into these dark moods. He feared that Saul’s moods were growing worse and worse, and might some day overcome Saul entirely. So he decided to find a successor for Saul.

Samuel found David, the son of Jesse. David was a shepherd, he was short and cheerful, with red hair and bright eyes. Samuel anointed David in secret, and told David that soon he be the next king of Israel.

Saul knew none of this. But soon he fell into one of his dark moods again. His servants said, “One of your dark moods has come again! Command us to go and find someone to come an play beautiful music for you. The music will ease your pain and lighten your mood.”

One of the servants said, “I know a young man named David, the son of Jesse. He plays beautifully on the harp. He is also a warrior, and he doesn’t gossip.”

“Fetch him here,” said Saul.

So David came to live with King Saul, and his music helped to soothe the king when one of his dark moods came upon him.

But Saul’s dark moods got worse and worse, and they came more and more frequently. Sometimes Saul wouldn’t recognize David, and several times he tried to kill him. Finally, it got so bad that David had to leave the king, and go live in the wilderness….

Source: Hebrew Bible, 1 Samuel 10-16, 31; 2 Samuel 1-3. The notion that Saul’s dark moods might have been a form of mental illness comes from lectures given by Carole Fontaine, professor of Hebrew Bible, at Andover Newton Theological School in 1997.

Abigail and David

Once upon a time, long before he became a king, when David was still running away from King Saul, afraid that Saul would kill him, he and his six hundred followers travelled to the wilderness of Paran.

In Carmel, which was near the wilderness of Paran, there lived a rich man named Nabal, who owned three thousand sheep and a thousand goats. Nabal was married to a woman named Abigail, who was clever and beautiful. Nabal himself, however, was rude and ill-natured; his name meant “The Fool.”

In the wilderness, David heard that Nabal was shearing his sheep. He decided to send ten young men to Nabal. David said to them, “Go to Carmel, find Nabal, and give him my greetings. Say to him, ‘Peace be upon your peace be upon your household, peace to all you have.’ Tell him that we have been living here among his shepherds, and we have not attacked them, nor have we stolen anything from them;— we have only the best intentions towards him and all those who work for him. You will arrive at his household on a feast day, and ask him if he would please give whatever food and drink he might have on hand to me and all of us.” David knew that anyone who lived in that land would feel compelled by the laws of hospitality to give at least some food to a band of men living in the wilderness.

David’s ten young men went to see Nabal the Fool, and they politely passed on David’s greetings, and his request for hospitality. But Nabal spoke to them harshly.

“Who is this David?” he said. “There are many servants who try to run away from their masters. Why should I take bread and meat and water away from the people who have been shearing my sheep, and give it to people who come from I know not where?”

When the ten young men came back to David and told him what had happened, he told four hundred of his men to strap on their swords.

“I protected his shepherds and everything else Nabal had in the wilderness, but for this good I did, he returned to me only evil,” said David. “Now we will go and kill every male in his household.”

They followed David towards Nabals’ house, while the remaining two hundred men stayed to guard the animals and the camp.

Meanwhile, one of the young men who worked for Nabal went to tell Abigail, Nabal’s wife, what had happened. The young man said that David had sent messengers to bring greetings to Nabal, but Nabal had only hurled insults at them. But, the young man said, when they had been out in the fields with Nabal’s sheep, David’s men had been good to them, and had even helped to protect them. And now David had decided to attack the household of Nabal, because Nabal was so bad-natured that no one can talk to him.

Abigail thought quickly. She ran and got two hundred loaves of bread, five sheep that had been butchered, one hundred clusters of raisins, two hundred cakes of figs, some grain, and some wine. She got her young men to load everything onto donkeys, and, without telling Nabal where she was going, she went along the mountain along the way she knew David would be taking.

When Abigail saw David, she got down from her donkey and hurried towards him. She fell to her knees, and bowed down before him.

“The guilt is mine alone,” she said. “My lord, please don’t take the words of ill-natured Nabal seriously. He is what his name says he is, a fool. I should have seen the young men you sent to our household, and then none of this would have happened.

“Now that I am here, there is no need to take vengeance, there is no need to shed blood. Please take all this food I have brought to you from Nabal’s household, and give it to your men.”

David listened to Abigail, and then said, “Blessed be your good sense, and blessed be you. If you hadn’t come to meet me, by the end of this morning my men and I would have killed every male in your household, and I would have incurred bloodguilt. Only Adonai, the God of the Israelites, is allowed to take vengeance. You have saved me from trying to take vengeance into my own hands.”

David and his men took everything Abigail brought to them. “See, I have done what you asked,” David said to her. “Go in peace.”

So Abigail went back to Nabal’s house. He was holding a feast, and he was very drunk, and acting very merry. Abigail waited until the next morning to tell him what had happened: that he had mortally insulted a band of six hundred warriors, warriors who had protected his shepherds, six hundred men to whom he at least owed ordinary hospitality. She told him how she had brought food to David and his men, and had intercepted them.

Nabal realized what a fool he had been, and his heart died within him. He became like a stone, and ten days later he died.

When David heard that Nabal had died, he sent messengers to Abigail, and asked her to marry him. And she agreed that she would marry him, and went off to live with David.

***

There is much more to the story of David, more than we have time for here….

At long last Saul was killed in battle, along with his son Jonathan. David cried when he heard that Saul had died, and that his best friend Jonathan had died, too. When Saul was killed, Samuel had died, too, and no one remembered that David was supposed to be the next king after Saul.

But eventually David did become king of Israel, and sat, as he was meant to do, in the throne once occupied by his old friend Saul. He was not only a warrior and a musician, he is said to have written many great poems, some of which were collected in a book known as the Psalms. And although he made mistakes, David ruled so wisely that we still tell stories about him today.

Source: Hebrew Bible, 1 Samuel 25.2-42.

How Moses Gained Freedom from the Pharaoh

The God of Israel came down to speak to Moses, and told Moses to go to the Pharaoh king of Egypt, and say to Pharaoh, “Let my people go, let them go free.” Moses didn’t want to do this, but God said he had to, and he did.

Moses said to Pharaoh, “Let my people go!” But Pharaoh was a hard-hearted man, and wouldn’t let the Israelites, the Jews, go free. So with God’s help, Moses took his staff while Pharaoh was watching, lifted it up, and struck the water of the Nile River. Immediately all the water in the river turned to blood, and that made all the fish in the river die. It did not smell good. And because the Egyptians got their water from the Nile, they had a hard time getting enough water to drink, or to wash with.

Well, you think that would have been enough to convince Pharaoh not to fool around with Moses — and to not fool around with the God of the Israelites. But the Pharaoh was a hard-hearted man. Moses came to Pharaoh, and said, “Now will you let my people go?” But Pharaoh said no.

This time Moses stretched out his staff over the river, the ponds and lakes and all the water, and with God’s help he let loose a plague of frogs. There were frogs everywhere! There were frogs in Pharaoh’s palace, frogs in everyone’s houses, frogs in people’s beds, so many frogs that the bakers put them into bread by mistake. Yuck! Bread with frogs in it. It tasted horrible.

Well, you think Pharaoh would have learned his lesson, but the Pharaoh was a hard-hearted man. Moses said, “Let my people go!” and Pharaoh just said, no.

This time Moses stretched out his staff and struck the dust of the earth, and with God’s help released a horde of gnats. Do you know what gnats are? They are little insects that bite you just like mosquitoes and when they bite you it’s just like a mosquito bite which swells up and itches, but gnats are so small you can’t see them. There were gnats everywhere, a plague of gnats, biting everyone all the time. It was most unpleasant.

Well, you think Pharaoh would have learned his lesson, but that Pharaoh was a hard-hearted man. Moses said, “Let my people go!” and Pharaoh just said, no.

So with God’s help, Moses sent a swarm of flies to plague the land. (If you’re keeping count, that’s the fourth plague Moses let loose on Egypt.) Flies everywhere! — on your food, in your eyes, everywhere.

But when Moses said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh just said, no. So with God’s help Moses made all the cows and chickens and other livestock get sick. No milk to drink! No eggs to eat! (That’s number five.) Everyone got very hungry.

But when Moses said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh just said, no. So with God’s help Moses made everyone in Egypt get pimples and boils that hurt like the dickens and looked nasty. (That’s number six.)

But when Moses said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh just said, no. So with God’s help Moses let loose thunder and hail, big hailstones that damaged all the crops. (That’s number seven.)

But when Moses said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh just said, no. So with God’s help Moses brought locusts into the country of Egypt. The locusts covered every inch of the land, and if there was anything left in the fields that the hail had not damaged, the locusts ate it up. (That’s number eight.) Now there was basically no food left to eat in all of Egypt.

But when Moses said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh just said, no. So with God’s help Moses brought a dense darkness over the entire land of Egypt, except for little bits of light that were in the houses of the Israelites. (That’s number nine.)

But when Moses said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh just said, no. This time, God said, “Moses, go tell Pharaoh that I, God, will make every first-born child die throughout the land of Egypt.” But God also told Moses that all the Jews should make a mark over their doors with the blood of a lamb, and that way God would know that God should pass over those houses, and not make the firstborn child die. That’s why it’s called Passover — God passed over the houses of the Israelites. (And that was the tenth, and the very worst, of the ten plagues.)

This time, when Moses went to Pharaoh and said, “Let my people go,” Pharaoh said, “Go! Go! You bring nothing but disaster to me and my kingdom.” But of course, it was all Pharaoh’s fault, because he should have set the Israelites free from slavery long before.

Source: Hebrew Bible, Exodus 7-11.

Moses and the Golden Calf

Moses and all the Israelites escaped from mean old Pharaoh, and Moses led them into the desert. They had to cross the desert, hot and dry, in order to get to the Promised Land, the place where they could live in peace and freedom.

They walked and they walked, day after day, for three whole months, until at last they reached Mount Sinai. They decided to camp there for a while, so they set up their tents.

Moses climbed up Mount Sinai, up to the very top, and while he was up there, the god sometimes known as Yahweh spoke to him. This god said to Moses, “All of you Israelites are going to be my special, chosen people. I will take care of you, and all you have to do is promise to obey me over all the other gods and goddesses.”

Moses agreed, and went back down Mount Sinai to tell the Israelites. All the Israelites had to do was to obey the god Yahweh, and Yahweh would take care of them. It’s always good to have a god looking out for you, so the Israelites agreed to obey this god.

Moses went back up Mount Sinai to report to the Yahweh. “They all promised to obey you,” Moses reported.

“Well, just to make sure,” said the god who was now the god of the ancient Israelites, “I’m going to appear at the top of this mountain as a dense dark cloud, filled with thunder and lightning. You come back up the mountain, I’ll talk with you, and then all the Israelites will know that I talk to you directly. That way they will trust you and listen to you.”

So Moses went back down Mount Sinai, and sure enough, the god of the Israelites appeared at the top of the mountain as a dense cloud. Moses went back up the mountain to talk with the god of the Israelites. All the other Israelites watched from the foot of the mountain.

Moses climbed up and up, and at last entered the dense cloud at the top of the mountain. The god of the Israelites started telling him about all the rules and laws the Israelites would have to obey. First of all, the god of the Israelites made ten laws against stealing, against murdering people, against lying. There was also a law saying the Israelites weren’t allowed to worship any other god or goddess. These first ten laws are sometimes called the “Ten Commandments.” Most of these laws still make sense, even today. And Moses went back down the mountain bringing those first ten laws to the Israelites.

Next day, Moses climbed back up the mountain for more laws. Yahweh gave him lots of laws. Some of these other laws sound strange to us today, like the law that said if one ox hurts another ox, the owner of the first ox has to sell it and divide the money with the owner of the second ox, and the owner of the second ox has to butcher it and divide the meat with the owner of the first ox. Yahweh had lots and lots of laws and rules for Moses to bring to the Israelites. Moses had to climb up and down that mountain quite a few times.

Then came a time when Moses stayed on top of the mountain for a really long time. The rest of the Israelites finally deicded Yahweh had abandoned them, and Moses wasn’t coming back. The Israelites decided to make a new god. They took gold and made it into the shape of a calf — a golden calf. They thought their new calf looked pretty cool, and they invented new worship services for their new religion, and had a big party to celebrate.

Just as the party was really getting going, Moses came back down the mountain with more laws.

“What’s going on here?” Moses said. “Don’t you remember that you promised not to worship any other gods? And here you all are, having a party, and worshipping some new god. You guys broke your promise!”

The Israelites looked a little shamefaced at first, but then some of them pointed out that Moses had been gone for a long time. For all they knew, Moses’s god had given up on the Israelites and gone somewhere else with Moses.

“Who’s on my side?” said Moses angrily. “If you still like Yahweh better than the golden calf, come with me!” A few people joined him. Moses made sure they all had swords, and then told them to go and kill anyone who was still worshipping that golden calf.

And they did.

Source: Hebrew Bible, Exodus 32.

STORIES FROM THE TALMUD

The Backwards Alphabet

One day, a man came to Rabbi Shamai to ask about becoming a Jew. Rabbi Shamai told him that if he wanted to become a Jew, he would have to learn the Torah, or the Jewish law.

The man asked, “Well then, how many types of Torah do you have?”

“We have two types of law, or Torah,” replied Rabbi Shamai. “We have the written Torah, and we have the oral Torah, the law as passed down by oral tradition.”

“I believe in the written Torah,” said the man. “But I don’t trust laws that are passed on by word of mouth. If laws aren’t written down, they are worthless. I will still become a Jew, on one condition: that you only teach me the written laws, but not the oral laws, not the spoken laws.”

Upon hearing this, Rabbi Shamai said that the man could never become a Jew, that he was disrespectful, and then Rabbi Shamai told the man to leave.

But the man still wanted to know about becoming a Jew, so he went to Rabbi Hillel.

Rabbi Hillel told him that if he wanted to become a Jew, he would have to learn Jewish laws — for example, he would have to learn the laws about eating kosher foods, and so on.

The man asked, “Well then, how many types of Torah do you have?”

“We have two types of law, or Torah,” replied Rabbi Shamai. “We have the written Torah, and we have the oral Torah, the law as passed down by oral tradition.”

“I believe in the written Torah,” said the man. “But I don’t trust laws that are passed on by word of mouth. If laws aren’t written down, they are worthless. I will still become a Jew, on one condition: that you only teach me the written laws, but not the oral laws.”

“Then I will accept you as a student,” said Rabbi Hillel. “First, you must learn how to read Hebrew, so I will teach you the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Repeat after me: aleph, bet, gimel, dalet, he, vav, zayin, khet, tet, yod, khaf, lamed, mem, nun, samekh, ayin, pe, tsadi, kuf, resh, shin, tav.”

The man repeated the entire Hebrew alphabet after Rabbi Hillel — “Aleph, bet, gimel, dalet,….” — until he had all the letters memorized.

The next day, the man came back to learn the written law from Rabbi Hillel. Rabbi Hillel said, “Let’s make sure you remember the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Repeat after me: tav, shin, resh, kuf, tsadi, pe, ayin, samekh, nun, mem, lamed, khaf, yod, tet, khet, zayin, vav, he, dalet, gimel, bet, aleph.”

The man looked confused. “But that’s not the way you taught them to me yesterday,” he said.

“Yes, that’s true,” said Rabbi Hillel, “and as you can see, you must learn to rely upon me and my teaching. In just the same way, you must learn to rely upon the spoken law.”

Source: Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sabbath 31a.

Standing on One Foot

A man came to talk with Rabbi Shamai, one of the most famous of all the rabbis, nearly as famous as Rabbi Hillel.

“I would like to convert to Judaism and become a Jew,” said the man. “But I don’t have much time. I know I have to learn the entire book you call the Torah, but you must teach it to me while I stand on one foot.”

The Torah is the most important Jewish book there is, and this crazy man wanted to learn it while standing on one foot? Why, people spent years learning the Torah; it was not something you can learn in five minutes! Rabbi Shamai grew angry with this man, and he pushed the man away using a builder’s yardstick he happened to be holding in his hand.

The man hurried away, and found Rabbi Hillel. “I would like to convert to Judaism and become a Jew,” said the man. “But I don’t have much time. I know I have to learn the entire book you call the Torah, but you must teach it to me while I stand on one foot.”

“Certainly,” said Rabbi Hillel. “Stand on one foot.”

The man balanced on one foot.

“Repeat after me,” said Rabbi Hillel. “What is hateful to you, don’t do that to someone else.”

The man repeated after Rabbi Hillel, “What is hateful to me, I won’t do that to someone else.”

“That is the whole law,” said Rabbi Hillel. “All the rest of the Torah, all the rest of the oral teaching, is there to help explain this simple law. Now, go and learn it so it is a part of you.”

Source: Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sabbath 31a.

The Rabbi and the Basket of Grapes

The Rabbis taught that if you are going to judge a case between two people, you must not accept any kind of money or gift from either person, you must not accept anything that might look like a bribe. You must show everyone that you will remain completely neutral, and completely honest.

Obviously, a judge should not accept money from either person in a lawsuit. But the rabbis taught that a judge must be so honest that he or she does not accept anything, no gifts, no favors, not even a kind word.

To show what they meant, they told this story:

Once upon a time, Rabbi Ishmael rented part of his land to a tenant-farmer. The tenant-farmer paid part of the rent by bringing fruits and vegetables to Rabbi Ishmael every Friday, the day before the Sabbath day.

But one week, the tenant-farmer brought some fruit to Rabbi Ishmael on a Thursday — a big basket full of luscious, ripe grapes. Rabbi Ishmael loved grapes, but before he took the basket he said, “Thank you for bringing the grapes, but why do you bring me grapes on a Thursday, instead of your regular day, Friday?”

“It’s like this, Rabbi,” said the tenant-farmer. “I have a lawsuit, and I would like you to be the judge for this lawsuit. And as long as I was coming up here to talk to you about being the judge, I thought I’d bring your regular weekly delivery of fruit. So I brought you your basket of grapes.”

“No, no,” said Rabbi Ishmael, “I cannot be your judge. Take the grapes back to your house, and I will go find two other rabbis to act as judge for you.”

Confused, the tenant-farmer took the basket of grapes back to his house, even though they were really Rabbi Ishmael’s grapes.

Rabbi Ishmael went out to find two other rabbis to act as judge in the lawsuit, and brought them to meet the tenant-farmer. The two other rabbis began to ask the tenant-farmer about the lawsuit, and the tenant-farmer answered as best he could.

Rabbi Ishmael stood to one side, watching and listening, and he thought to himself, “Why doesn’t the tenant-farmer give better answers?” At one point, Rabbi Ishmael was on the point of breaking in and telling the tenant-farmer what to say, but he caught himself in time.

“Look at what has happened to me,” said Rabbi Ishmael to himself. “Here I am, secretly hoping that the tenant-farmer will win his case, and I didn’t even accept a bribe. I didn’t even accept the grapes that were really mine, but came a day early. What would I have done if I had accepted a real gift, a real bribe!”

Source: Babylonian Talmud, Kethuboth 105b

The Fox and the Fish

Once upon a time, the wicked Roman government issued a decree: no more would the Jews be allowed to study the Torah and the law.

But Rabbi Akiva seemed to ignore the decree. He gathered people together quite openly, and taught them the Torah and the law. Pappas, the son of Judah, took him aside and said, “Rabbi Akiva, do know what could happen to you? Aren’t you afraid the Romans will punish you?”

“Let me tell you a story,” said Rabbi Akiva, and he told this story:

***

Once upon a time, there were many small fish who lived in a stream. One day, fox walked alongside the stream, and noticed that all the fish were darting to and fro, as if they were afraid of something.

“O fish, o fish,” said the fox, “why are you swimming around so? What is it that you are trying to escape?”

“We are trying to escape the nets that the humans have put in the stream to catch us,” said the fish.

“Oh, ho,” said the fox. “Then perhaps you should come up here and walk on dry land alongside me, just as your ancestors used to walk beside my ancestors years and years ago. That way you can escape from the nets of the humans.”

“What, go up on dry land!” said the fish indignantly. “You have a reputation for being smart, but that is a stupid thing to say. We may be afraid of what’s going on here in the water where we feel comfortable, but it would be much worse for us up in the thin air where we would surely die.” And so the fish stayed in the water, and did not try to walk beside the fox on dry land.

***

Rabbi Avika said, “Now you can see that we are just like the fish in the stream.”

Pappas asked the rabbi to explain.

“It’s like this,” said Rabbi Avika. “If we neglect the Torah, if we neglect what is central to our religion, we would be like fish out of water, and we would die. It is written in the Torah, ‘For that is your life and the length of your days.’ Perhaps we will suffer if we do study the Torah, but we know we will surely die if we don’t.”

Not long after that, the wicked Romans arrested Rabbi Akiva for teaching and studying the Torah. He was roughly thrown into the Roman prison, and there to his surprise he found Pappas.

“Pappas, what are you doing here?” asked Rabbi Akiva.

“O rabbi,” said Pappas, “you were right. I have been thrown into prison for nothing important. At least you have been thrown in prison for something worth dying for.”

And when Rabbi Akiva was killed by the Romans, he died in peace with the words of the Torah on his lips.

Source: Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Berakoth 61b

STORIES FROM THE CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURES

The Empty Jar

Jesus and his followers were traveling from village to village in Judea so that Jesus could teach his message of love to whomever would hear it. They had spent the day in a village where some people wanted to hear what Jesus had to say, and many others didn’t seem to care. That evening, they stayed on the outskirts of the village, and as they were eating dinner, Jesus said, “Let me tell you what it will be like when the kingdom of heaven is finally established….”

Once upon a time [said Jesus], there was a woman, just an ordinary woman who happened to live in a very small village that had no marketplace of its own. At the harvest season, the crops having been gathered in, the woman decided to walk to a larger village, two or three miles away, where there was a market.

She started off early in the morning. She brought along some things her family had grown to sell in the market, and she brought along a large pottery jar with two big handles. Since she was an ordinary villager, or course she did not have fancy bronze jars, nor did she even have well-made pottery jars with pretty decorations. The potter who lived in her village was not very good at what he did, so her jars were without decoration, and not very well made.

She arrived at the marketplace, and sold everything she had brought. Then she purchased a large amount of meal, or coarsely-ground flour. She filled her jar with the meal, tied the handle with a strap of cloth, and slung the jar over her back.

The path home was steep and rough, and by now the day was hot. She walked along, putting one foot in front of the other, and she did not notice anything besides the heat and the rough path.

But one of the handles to the jar broke off, and the jar slowly tipped to one side. Bit by bit, the coarsely-ground flour spilled out on the path behind her. Bit by bit, the jar tipped even further. Before she reached home, all the flour in that jar had spilled out.

At last the woman reached home. She put the jar down, and discovered that it was empty. That is what the Kingdom of Heaven will be like.

Source: Adapted from the Gospel of Thomas, chapter 97.

How To Feed Five Thousand People

Once upon a time, Jesus and his disciples (that is, his closest followers) were trying to take a day off. Jesus had become very popular, and people just wouldn’t leave him alone. Jesus and the disciples wanted a little time away from the crowds that followed them everywhere, so they rented a boat and went to a lonely place, far from any village.